Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.22 no.2 Zaragoza abr./jun. 2008

Gender differences in response to war stress in hospital personnel: Does profession matter? A preliminary study

Nir Essar*, Menachem Ben-Ezra**, Shai Langer***, Yuval Palgi****

* Psagot Institute, Tel Aviv

** School of Social Work, Ariel University Center of Samaria, Ariel

*** Department of Psychology, Derby University Branch in Israel, Ramat-Efal

**** Department of Psychology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv. ISRAEL

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: To study gender differences and the impact of trauma on hospital personnel during war. In addition, to test the relationship between gender and PTSD symptoms via mediation model.

Methods: A random sample of physicians, nurses and administrative staff (n = 106) that were assessed for demographics, and PTSD symptoms a month after the war between Lebanon and Israel erupted.

Results: Women had higher IES-R scores in comparison to men (25.27 vs. 16.18). Gender differences were reduced when accounted for profession. In each profession, no significant gender differences were found. The results of the mediation model showed significant mediation by profession and education.

Conclusions: These results may suggest that gender differences in response to traumatic events may not be explained by exposure per se, but rather may result from various possible factors such as profession, education and control over the situation. The results warrant further longitudinal study.

Key words: Trauma, Hospital, War, Stress, Gender

Introduction

The research regarding gender differences after posttraumatic exposure is very extensive and well substantiated in the literature1. The literature shows that the prevalence of PTSD among women is about twice than in men2. In addition, each gender has a different exposure profile to traumatic events with men more frequently exposed to armed conflict and violent crime while women are more exposed to sexual assault1,2. Although the prevalence difference remains even when men and women were exposed to the same type of traumatic events1.

Only few studies have systematically examined the effect of exposure to extreme stress on men and women hospital personnel3-6. However, these studies presented different results. Luce et al.3 reported no sex differences among hospital personnel in PTSD scores after the Omagh Bomb. They found a profession effect showing that physicians were more resilient than nurses were. Cognitive theories of traumatic stress support this view on one hand by claiming that perceived threat and control over the situation are important determinants of posttraumatic responses7-9, and may explain the dominant effect of profession over gender in medical setting. The main limitation of Luce's et al.3 study is that only half of the participants were exposed to trauma. Weiniger et al.6 found no sex differences among surgical physicians. Their sample though was imbalanced with less than 20 percent of women. Laposa and Alden5 found no occupation and sex differences, but they explain it with their sample imbalance that biases the results. On the other hand, Grieger et al.4 reported significant sex differences among hospital personnel at the time of a sniper shooting. The main limitations of their study is the neglect of profession groups among hospital personnel, the fact that none of the hospital's personnel were exposed to the sniper shooting, none of the victims of the sniper shooting had family ties with any of the hospital personnel, and none of the victims were admitted to the hospital where the study was conducted. Likewise, previous studies examined exposure to victims of bombings, terror attacks and sniper shootings, which represented only a single trauma, or indirect exposure to multiple traumas3,4,6,10 but not a prolonged exposure to trauma. There are also number of studies that examined medical crew's (ambulance drivers, first aid teams, medics, paramedics, medical technicians, etc.) reactions to traumatic exposure11-13. These studies present a different setting comparing to the hospital setting and contain, usually, many methodological limitations due to their field study nature. Some of them do not includes profession13 others are not controlling for the nature of the traumatic events11,13 and most of them are suffer from neglecting gender in sampling, design and statistics11-13.

The present study addresses this issue by assessing PTSD symptoms among men and women hospital personnel who were exposed to prolonged war stress. To the best of our knowledge, no earlier study has been conducted regarding gender differences among hospital personnel exposed to war stress.

Based on previous research1,3,4,14, we formulated the first hypothesis:

a. Women hospital personnel will exhibit higher level of PTSD symptoms than men will.

The second hypothesis is based on a mediational model15. The assumption is the correlation between gender and PTSD symptoms is mediated by demographic factors such as age, martial status, profession and education. This mediation will be significant and diminish gender differences. The second hypothesis will derive from this proposed model as presented below:

b. When profession will be taken into account, the gender differences will reduced significantly, showing lower level of PTSD scores among physicians in comparison to nurses and administrative staff.

Method

Events

On 12 July 2006 at 9:30, war erupted between Israel and Lebanon. Israel suffered 163 fatalities (44 civilians and 119 soldiers) and 2400 wounded (2000 civilians and 400 soldiers). During the war, hundreds of missiles targeted the Northern city of Haifa. The Rambam hospital is the largest and most important hospital in northern Israel and serves a population of one million people with 75,000 hospitalizations and 500,000 admissions each year. A large proportion of the civilians and military casualties were admitted to hospital during the war. The Hospital itself was also targeted, with 40 missiles landing in the hospital vicinity.

Participants

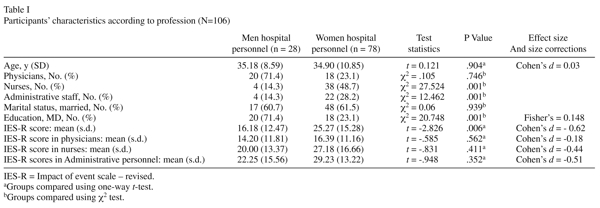

A sample of hospital personnel were selected at random at the fifth week after the war begun16. The initial sample included physicians, nurses and administrative staff (n = 126). The response rate was 84%. Those who declined were asked about their reasons for refusal. The most common reason for refusing was 'no time'. The final sample consisted of 106 participants, 78 women and 28 men. Of them, 38 physicians, 42 nurses, and 26 administrative personnel (see Table I). There were no differences between respondents and non-respondents in demographic data (age, gender, profession). The study took the form of a short screening interview and survey conducted on the week of August 12. None of the participants had a history of mental disorders and no prior exposure to war related stress. All the participants were under missile attacks with immediate threat to life and exposure to war casualties both military and civilian.

Instruments

Demographic measures included age, gender, marital status and profession. PTSD symptoms assessed with the 22-item Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R)17 which rated severity of intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms over the past week on a 5-point severity scale (0 = not at all; 4 = extremely; alpha = 0.92). The scoring was the sum of the items (range 0-88). Total scores ≥ 33 indicated a clinical level of distress18.

Data analysis

Demographic differences between the groups were tested using one-way analysis of covariance (ANOVA) and chi square tests. These tests were followed by a set of t-tests for comparing the IES-R scores based on gender in each profession group.

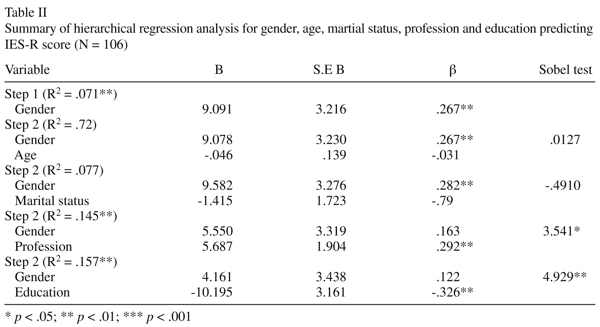

In order to test the mediation model, a two-step hierarchical regression analysis was conducted for each possible mediator. In the first step, gender was entered into the regression in the first block. In the second step, different mediators (age, martial status, profession, education) were entered separately into the second block. The method used to test mediation was Sobel test15,19.

Finally, ANCOVA test was conducted in order to examine the associations between gender and IES-R scores while adjusting for age, martial status, profession, and education. Partial h2 were conduced to each factor in the ANCOVA in order to measure its effect size. All the analyses were calculated using SPSS program (SPSS, version 11.5, Chicago, IL).

Results

In a conducted t-test comparing men and women hospital personnel in their IES-R scores, significant gender differences were found with moderate-high effect size (Table I). This result is in line with our first hypothesis. In addition, there were no gender differences in age and marital status. However, when we introduced the variable profession, no gender differences were found when comparing gender in IES-R scores in each profession group using a t-test (Table I). These results are in line with our second hypothesis. In order to substantiate these results, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with PTSD symptoms as the dependent variable and predictors entered in the following two steps: (a) gender, (b) mediator variable (age, martial status, profession, education), The process was repeated to each mediator separately. Profession and education were significantly related to the PTSD symptoms, after controlling for gender (see Table II). The Sobel test19 revealed a significant effect of profession (Sobel test = 3.541, p< .05) and education (Sobel test = 4.929, p< .01). Finally, the ANCOVA analysis showed that gender was not associated with higher IES-R scores (F = 1.738, df = 1,100, p= 0.190). The same results were found also in age for IES-R scores (F = 0.051, df = 1,100, p = 0.822), marital status for IES-R scores (F = 0.355, df = 1,100, p= 0.552), profession (F = 0.219, df = 1,100, p = 0.641), and education (F = 1.708, df = 1,100, p= 0.194). See Table III for more details. The effect size for all the ANCOVA factors were found to be small (Max partial h 2= .017), which is considered small according to Cohen's standard20.

Discussion

Previous medical settings studies on gender differences in response to traumatic stress have yielded mixed results3,4,21. We examined the extent to which this gender difference might be explained by other factors like profession in medical setting. In this study, we controlled for the type of trauma, and exposure contrary to previous research3,4. Our results showed that in first glace there is gender differences in PTSD symptoms, which confirms our first hypothesis. However, with the introduction of profession the gender differences were reduced dramatically confirming our second hypothesis. Our results indicated that gender differences among hospital personnel in response to war stress, may be explained by profession. It seems that almost regardless for gender, physicians were more resilient than nurses and administrative staff. There are some explanations for our results. First, physicians have more perceived control over situations in medical setting, due to their position, in comparison to nurses and administrative personnel. This control lead to much more resilience as found in other studies that examined stress factors among physicians22. Perceived control over the situation is also known to moderate stress23. During the war, physicians were able to cope better as part of adjustment technique, and as part of their role. Furthermore, physicians are known to detach themselves in stressful situations in order to stay focused. This emotional control is a contributor to stress control and moderation that may lead to better adjustment8,23. Since men and women physicians undergo the same training and use similar coping techniques, and had similar demographic features, they are a very homogenic group. Therefore, the gender differences that found in other settings may loose their significance. Second, perceived threat was found to be more dominant among nurses in comparison to physician while facing continues traumatic event such as exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)21. Third, it is assumed that nurses are more likely to identify with patients, which might result in higher risk for the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms24. Moreover, nurses have different responsibility for the medical status of the patients, less forensic responsibility and authority compared with physicians3. This leads to closer relationships with the patients that enhance the identification that was mentioned earlier.

In sum, our results may point out that in medical setting during exposure to extreme stress gender differences are secondary to profession.

There are some limitations to this study. First, no actual diagnosis was made. Although, studies18 have shown that IES-R using cutoff score of 33 has the best diagnostic accuracy for predicting PTSD symptoms according to DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994). Second limitation is the study's cross-sectional design. Longitudinal studies are needed, preferably with an assessment prior to severe events and with follow-up assessments to study the course of symptoms. Another limitation is the lack of detailed demographic and personal information about the participants, which limited the ability to control over variables like personality traits etc. Future studies should assess the nature of wartime exposures (patient contact versus personal threat of injury or death) to assess the relative contribution of different exposures to the development of stress symptoms in men and women hospital personnel. Third, no gender differences among the responders were found in this study. Nevertheless, it is possible that the sample is skewed towards higher levels of distress. This can be addressed by future studies that will examine locus of control and compare it to gender. Lastly, it is important to mention the small numbers of men in the nurses and administrative staff that might influence the results. The moderate effect size these groups had might imply for possible relations between sex and PTSD symptoms.

Although exposure to prolonged war stress with actual threat to life is quite scarce in medical setting, it seems to affect nurses and administrative staff more than physicians. Since it is, likely that hospital personnel will be affected by crises like this in the future, policies for preventing and reducing the prevalence PTSD should be accompanied by action to mitigate the effects of war stress on the mental health of hospital personnel who are generally under elevated stress in hospital setting.

References

1. Norris FH, Foster JD, Weisshaar DL. The epidemiology of sex differences in PTSD across developmental, societal, and research contexts. In: Kimerling R, Ouimette P, Wolfe J, Eds. Gender and PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. p. 3-42. [ Links ]

2. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54(11): 1044-1048. [ Links ]

3. Luce A, Firth-Cozens J, Midgley S, Burges C. After the Omagh bomb: Posttraumatic stress disorder in health service staff. J Trauma Stress 2002; 15(1): 27-30. [ Links ]

4. Grieger TA, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Reeves JJ. Acute stress disorder, alcohol use, and perception of safety among hospital staff after the sniper attacks. Psychiatr Serv. 2003; 54(10): 1383-1387. [ Links ]

5. Laposa JM, Alden LE. Posttraumatic stress disorder in emergency room: Exploration of cognitive model. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(1): 49-65. [ Links ]

6. Weiniger CF, Shalev AY, Ofek H, Freedman S, Weissman C, Einav S. Posttraumatic stress disorder among hospital surgical physicians exposed to victims of terror: A prospective, controlled questionnaire survey. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67(6): 890-896. [ Links ]

7. Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [ Links ]

8. Benighta CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: the role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav Res Ther 2004; 42(10): 1129-1148. [ Links ]

9. Shalev AY, Tuval R, Frenkiel-Fishman S, Hadar H, Eth S. Psychological Responses to Continuous Terror: A Study of Two Communities in Israel. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163(4): 667-673. [ Links ]

10. Kerasiotis B, Motta RW. Assessment of PTSD symptoms in emergency room, intensive care unit, and general floor nurses. Int J Emerg Ment Health 2004; 6(3): 121-133. [ Links ]

11. Okada N, Ishii N, Nakata M, Nakayama S. Occupational stress among Japanese emergency medical technicians: Hyogo Prefecture. Prehosp Disast Med 2005; 20(2): 115-121. [ Links ]

12. Lubin G, Sids C, Vishne T, Shochat T, Ostfield Y, Shmushkevitz M. Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder among medical personnel in Judea and Samaria areas in the years 2000-2003. Mil Med 2007; 172(4): 376-378. [ Links ]

13. Maguen S, Turcotte DM, Peterson AL, Dremsa TL, Garb HN, McNally RJ, et al. Description of risk and resilience factors among military medical personnel before deployment to Iraq. Mil Med 2008; 173(1): 1-9. [ Links ]

14. Walsh BR, Clarke E. Post-trauma symptoms in health workers following physical and verbal aggression. Work & Stress 2003; 17(2): 170-181. [ Links ]

15. Baron RM., Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 51(6): 1173-1182. [ Links ]

16. Ben-Ezra M, Palgi Y, Essar N. Impact of war stress on posttraumatic stress symptoms in hospital personnel. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007; 29(3): 264-266. [ Links ]

17. Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale - revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, eds. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford; 1997. p. 399-411. [ Links ]

18. Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale revised. Behav Res Ther 2003; 41(12): 1489-1496. [ Links ]

19. Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, eds. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. p. 290-312. [ Links ]

20. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [ Links ]

21. Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, Lee CY, Chiu NM, Yeh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 185(2): 127-133. [ Links ]

22. Kivimaki M, Sutinen R, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Räsänene K, Töyry S, et al. Sickness absence in hospital physicians: 2 year follow up study on determinants. Occup Environ Med 2001; 58(6): 361-366. [ Links ]

23. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 2001; 52(1): 1-26. [ Links ]

24. Regehr C, Goldberg G, Hughes J. Exposure to human tragedy, empathy, and trauma in ambulance paramedics. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2002; 72(4): 505-513. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Menachem Ben-Ezra

School of Social Work,

Ariel University Center of Samaria,

Ariel 40700 Israel

Tel: +972 3 6760285

E-mail: menbe@ariel.ac.il

Received 24 August 2007

Revised 5 April 2008

Accepted 18 April 2008