My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The European Journal of Psychiatry

Print version ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.23 n.3 Zaragoza Jul./Sep. 2009

First admissions for psychoses in Eastern Piedmont-Italy

Patrizia Zeppegno*, Manuela Probo*, Daniela Ferrante**, Lisa Lavatelli*, Paola Airoldi*, Corrado Magnani**, Eugenio Torre*

* Department of Medical Sciences, University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara

** Unit of Medical Statistics and Cancer Epidemiology, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Eastern Piedmont and CPO - Piemonte, Novara. Italy

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: 1) To identify the sociodemographic, anamnestic characteristics and presentation symptoms of patients, at the time of first hospitalization, associated with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenic versus non-schizophrenic psychoses; 2) to define risk factors, at the time of the first admission, for a rehospitalization, regardless of reasons for readmission; 3) to assess the diagnostic stability between first and second hospitalization.

Methods: This study includes 245 patients first admitted to the University Psychiatric Clinic of Novara in a period of seven years, discharged with a diagnosis of psychosis as reported in the Discharge Register (ICD-9-CM codes 290-299). Data were collected by consulting medical records and registers of community-based services of the South Novara Mental Health Department. A logistic regression model was used to determine the characteristics associated with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia. The relationship between the risk of rehospitalization and patients characteristics was studied using Cox,s regression analysis.

Results: Risk factors for a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia were age, compulsory admission, positive symptoms, and previous non-psychotic psychiatric episodes. Risk factors for rehospitalization were a diagnosis of schizophrenia, an age of less than 40 years, the absence of a stable affective relationship, and living with the family of origin. The 92% of the patients diagnosed as schizophrenic on the first hospitalization had the same diagnosis on readmission.

Conclusions: Schizophrenia differs from other psychoses in terms of the greater prevalence of both some symptomatological characteristics and an history of previous non psychotic episodes. Some sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at the time of the first hospitalization can provide indications useful in preventing rehospitalization.

Key words: Psychoses; Schizophrenia; Rehospitalization.

Background and objectives

A psychotic episode may be due to many conditions, including schizophrenia, mood disorders, substance use or a medical general condition. Particularly, substance use or the presence of a general medical condition may influence the presentation symptoms of any psychiatric disorder and eventually determine a psychotic breakdown in schizophrenic and manic patients. It may be difficult to make a differential diagnosis at the time of presentation although this is important for defining prognosis and therapy.

Most psychotic episodes can be attributed to schizophrenia, a ubiquitously widespread pathology throughout the world1-3 that has a cumulative lifetime incidence between 0.5% and 1.6%4, whereas the totality of psychotic syndromes was found to have an estimated cumulative incidence of 3-3.4%5. The first hospitalization due to schizophrenia often marks the end of a prodromic period that lasts an average of five years; depressive and negative symptoms appear first, followed by the first signs of cognitive decline and social dysfunctioning6-11.

Some recent studies indicate that early intervention improves the prognosis of both schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and that starting treatment later leads to a more severe symptoms and to a worse drug therapy response12-14. Otherwise a recent report indicates that the intensive early-intervention program improved clinical outcome after 2 years, but the effects were not sustainable up to 5 years later15.

As the prodromic period of schizophrenia often passes unobserved, the first hospitalization represents the first contact with psychiatric services in many cases, and can therefore be considered a good indicator of the incidence of the illness16. In accordance with Italian law, such admissions may be voluntary or compulsory (for a renewable period of 7 days, that can also be revoked earlier)17.

The first aim of the study was to identify which of the characteristics present at the time of the first hospital admission were associated with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenic or non-schizophrenic psychoses. The second aim was to define which of the factors assessed at the time of the first admission indicates a risk of rehospitalization. The third aim was to assess, in patients readmitted to hospital, the concordance of the discharge diagnosis between first and second hospitalization.

The University Psychiatric Clinic, in which the study was conducted, belongs to the South Novara Mental Health Department (Piedmont, Italy). The catchment area of the Department has a population of about 182,000 people, 56% of whom are resident in the town of Novara. In addition to the University Psychiatric Clinic (14 beds, with 1.7 members of hospital staff per bed), the Department has three Day Hospitals (one inside the hospital), two Day Centres, seven Residential Facilities (two Therapeutic Communities and five apartment blocks with a total of about 60 beds), and outpatients clinical activity18. There is also a liaison with Pediatric Neuropsychiatry across staff meetings and possibility of consultation of clinical charts.

Methods

The study includes 245 patients first admitted to the University Psychiatric Clinic of Novara in a period of seven years, resident in the same area, and discharged with a diagnosis of psychosis as reported in the Discharge Register (ICD-9-CM codes 290-299).

We have considered the following diagnoses: pre-senile and senile states (code 290), alcohol induced syndromes (code 291), drug induced psychosis (code 292), transient organic psychotic states (code 293), schizophrenic psychosis (code 295), paranoid states (code 297), other non organic psychoses (code 298). Affective psychoses (code 296) include single maniacal episode (code 296.0), single/recurrent depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (codes 296.24 and 296.34), bipolar disorder (codes 296.4, 296.5, 296.6, 296.7). We have finally divided the study patients in two diagnostic groups: schizophrenic psychosis (ICD-9-CM code 295) and non schizophrenic psychoses.

Medical records were reviewed in order to collect the following data: gender, age, education, occupational history, marital status, living circumstances (alone, with their family of origin, with their own family, or in a community), family history of psychiatric illness (i.e. the presence of a first-degree relative with a current or previous history of a disorder requiring the intervention of the psychiatric services), the type of admission (compulsory or not), the number of days spent in hospital, and any previous psychiatric history (defined as any known contacts with public or private psychiatrists, public or private hospital admissions, continuous contacts with a pediatric neuropsychiatrist because of non-psychotic symptoms).

Family and personal history of psychiatric illness were assessed by consulting clinical charts and the registers of the diversified community-based services belonging to the South Novara Mental Health Department.

The symptoms present at the time of the first hospitalization were evaluated by reading the admission reports, in which positive and negative symptoms of PANSS (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale) two sub-scales are systematically considered, by means of a specific checklist, in terms of present or not present19.We have considered the presence of at least one symptom for each subscale in order to classify the two categories: "presence of positive symptoms" and "presence of negative symptoms". We have also considered confusion and agitation in terms of present or not present.

In order to identify which of the characteristics present at the time of the first hospital admission were associated with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenic or non-schizophrenic psychosis (first aim), a logistic regression model, using the forward selection method, was applied. The odds ratios and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. The significance of each individual variable was assessed using the likelihood ratio test (LRT), with a p value < 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

With regards to the risk factors for readmission (second aim), rehospitalization curves were constructed on the basis of a survival analysis. We have considered as follow-up the period of time from the date of first hospitalization to the date of second admission or the last known information by reading medical records. All of the patients had a follow-up of at least one year.

The risk of rehospitalization was considered regardless of reasons for readmission; diagnosis at the time of rehospitalization was evaluated in terms of diagnostic stability or not.

The cumulative risk was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method20, and the 95% CI using Greenwood's formula21.

The rehospitalization curves were constructed on the basis of gender, age (< 40 versus > 40 years), education (high school diploma or degree versus middle school diploma or less), occupational history, marital status (single or widowed or separated versus married), living circumstances (family of origin, own family, community versus living alone), family history of psychiatric illness (yes versus no), personal history of previous psychiatric episodes (yes versus no), type of admission (compulsory versus voluntary), days of hospitalization (> 10 versus < 10 days), psychomotor agitation at the time of the first hospitalization (absent versus present), confusional symptoms (absent versus present), positive symptoms (present versus absent), negative symptoms (present versus absent), and a discharge diagnosis of schizophenia versus other diagnoses. The significance of the differences between the curves was assessed using the log-rank test for homogeneity, with p values < 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

The relationship between the risk of rehospitalization and patients characteristics was studied using Cox's regression analysis (or proportional risks model), and the hazard ratio (HR) was calculated: a value of HR > 1 indicates a higher risk in the group with a given characteristic than in the reference group.

The concordance between first and second hospitalization (third aim) with regards to diagnosis was also studied.

STATA v8 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and SAS software (release 8.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) were used to perform all statistical analyses.

Results

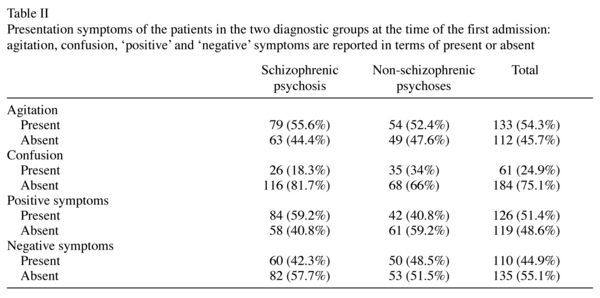

Table I and Table II show the sociodemographic, anamnestic characteristics and presentation symptoms of the study patients by discharge diagnosis of schizophrenic psychosis (142 patients, 58%) or non-schizophrenic psychoses (103 patients, 42%).

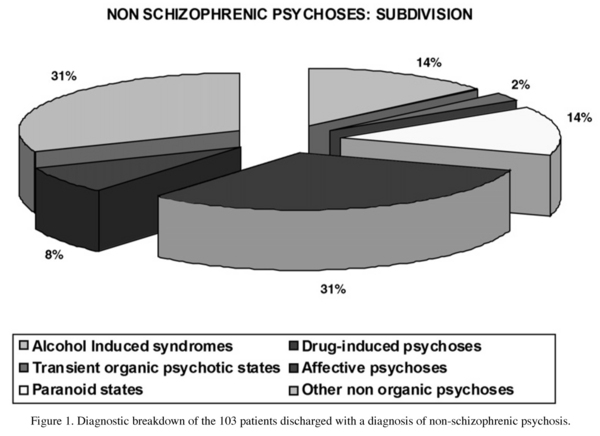

Figure 1 shows the diagnostic breakdown of the 103 patients discharged with a diagnosis of non-schizophrenic psychosis.

With regards to the first aim of the study, the multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the main characteristics at the time of first admission associated with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenic psychosis were age (OR = 0.90 per year; 95%CI 0.88-0.93), type of admission (compulsory versus voluntary: OR = 4.18; 95%CI 1.34-13.0), positive symptoms upon admission (present versus absent: OR = 2.22; 95%CI 1.06-4.66), and a history of previous non psychotic episodes (present versus absent: OR = 2.19; 95% CI 1.0-4.8). The likelihood ratio test value of the model including all these variables (df = 4) was 114.6 (p < 0.0001). The other considered variables were not statistically significant.

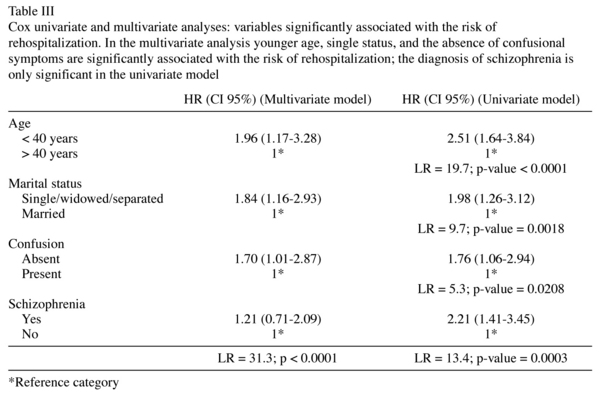

Figure 2 shows rehospitalization curves in the two study groups and Table III shows the results of the Cox univariate and multivariate analyses with the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals of the variables significantly associated with the risk of rehospitalization (second aim of the study).

One hundred patients (41%) were rehospitalized: three years after the first admission, the cumulative risk of a second hospitalization was 36.7%; 21% of the subjects were followed up for a period of less than three years. The mean time of follow-up between the first hospitalization and the second one or the end of follow-up (whichever occurred first) was 3.1±2.5 years. Among subjects with a diagnosis of schizophrenic psychosis the mean time of follow-up was 3.0 ± 2.4 years, and 3.4 ± 2.5 years among subjects with non-schizophrenic psychosis (Figure 2).

The multivariate analysis showed that the variables significantly associated with the risk of rehospitalization were age (< 40 versus > 40 years: HR = 1.96; 95% CI 1.17-3.28), marital status (single versus married: HR = 1.84; 95% CI 1.16-2.93), and the absence of confusional symptoms at the time of first admission (absent versus present: HR = 1.70; 95% CI 1.01-2.87) (Table III).

The diagnosis of schizophrenia was not statistically significant in the multivariate model (HR = 1.21; 95% CI 0.71-2.09), but it was significant in the univariate model (HR = 2.21; 95% CI 1.41-3.45). The likelihood ratio test of the multivariate model (df = 4) was 31.3 (p < 0.0001). Particularly age is one of the most important predictor of readmission; HR of schizophrenia adjusted by age was 1.45 (95% CI 0.86-2.50) (Table III). The mean age of patients readmitted was 37.4±15.4 years, and 49.4±19.8 for the patients not readmitted.

The univariate analysis, but not the multivariate one, also showed that patients living with their family of origin were at significantly greater risk of readmission than those living alone (HR = 1.73; 95% CI 1.01-2.97). Patients living with their own family (HR = 0.59; 95% CI 0.32-1.07) or in a community (HR = 1.3; 95% CI 0.61-2.68) were not at greater risk of readmission than those living alone. The likelihood ratio test of the univariate model (df = 3) was 19.1 (p = 0.0003).

With regards to the third aim of the study, 92% of the patients diagnosed as schizophrenic on the first hospitalization had the same diagnosis on readmission. The 84% of the 100 patients readmitted to hospital had the same discharge diagnosis on both hospitalizations.

Conclusions

The published literature generally considers three diagnostic groups when referring to psychotic episodes: schizophrenic spectrum psychoses, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorders with psychotic symptoms22. In our sample the most frequent discharge diagnosis was schizophrenia according to ICD-9-CM. Affective psychoses were less represented.

With regards to the first aim, we found some risk factors, at the time of the first hospitalization, for a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenic versus non-schizophrenic psychosis.

With regards to age, in our sample it has been shown that the risk of a diagnosis of schizophrenic psychosis decreases with age at a rate of about 10% per year. In literature, at the general population level, the age-specific incidence of schizophrenia is highest in the early 20s and decreases with age23-26. However, a recent study conducted in Finland suggests that increasing age does not decrease the risk of schizophrenia up to age of 4027.

In terms of symptoms, we found that the presence of at least one of the PANSS positive symptoms was a risk factor for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. On the other hand the PANSS negative symptoms were equally prominent in the two study groups. Some published data, regarding first episode psychotic patients, indicate that symptoms classified as "negative" upon admission are more frequent in subjects finally recognized as schizophrenic than in those with affective disorder, but at the time of the first hospitalization it can be difficult to differentiate between "negative" symptoms and depressive symptoms28. The literature also suggests that "negative" symptoms can be already present at the time of the first psychotic episode in schizophrenic patients29.

We found that the presence of any previous non psychotic episode is related to a greater risk for a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia. Published data report that first episode psychotic patients later diagnosed as schizophrenic frequently have a history of psychiatric illness corresponding to prodromic symptoms, such as previous psychotic or neurotic symptoms, or emotional or behavioural disorders30. Other studies have demonstrated that changes in mood precede the first admission by some years31. In literature various approaches have been used to assess the duration of untreated illness (DUI) in schizophrenia. Very few studies have separately examined DUI from prodromal versus psychosis onset in the same patients32-34. This suggests that an accurate collection of anamnestic data especially about the presence of previous psychiatric episodes in first admitted patients can be helpful in making a correct differential diagnosis. In comparison with patients with other psychoses, schizophrenic patients have a longer period of disease before the diagnosis is made35, and only 12% has been in contact with psychiatric services before their first hospitalization36.

Regarding the type of admission, we found that compulsory first admission is a risk factor for a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia. In other samples including first episode psychotic patients, the literature indicates a diagnosis of schizophrenia as a risk factor for compulsory hospitalization36. In a recent national survey conducted in Italy about patterns of admission to acute psychiatric in-patient facilities, non affective psychoses accounted for a large extent of compulsory admissions37. Sociodemographic characteristics, a positive family history of any psychiatric illness, and any non-positive symptoms, were all not significantly associated with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia. Our failure to find any statistically significant differences in terms of sociodemographic characteristics confirms previously published data concerning affective and schizophrenic psychoses38. In our sample there is no substantial gender difference in the prevalence rate of schizophrenia versus other psychoses. In literature it has been found that the incidence of schizophrenia is higher in males39,40.

About the second aim of the study, our multivariate analysis showed that the risk of rehospitalization was almost twice in subjects aged less than 40 years at the time of the first admission. Younger age was also associated with a greater risk for a diagnosis of schizophrenia, which resulted in higher rehospitalization in the univariate but not in the multivariate analysis: in our sample younger age resulted more important than diagnosis for the risk of rehospitalization. A possible explanation is that elder patients are often hospitalized in other services different from psychiatric emergency units. Consistent with this consideration, the absence of confusional symptoms, prominent in senile psychoses, was a risk factor for readmission.

Some published data show that schizophrenic spectrum psychoses are not associated with rehospitalization rates higher than those of affective disorders with psychotic symptoms38 also because the prognosis and course of schizophrenia is variable41. In literature some data indicate that 60% of the patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia become chronically affected, but only 25% are rehospitalized within 5-6 years of diagnosis42. In another recent study only 20% of patients require rehospitalization within the first year of diagnosis43. It is important to underline that prognosis of schizophrenia depends on a correct diagnosis but also on the definition of specific outcomes such as remission or full recovery44.

In our study the characteristics of the familial and social context at the time of first admission proved to be statistically significant in determining the risk of rehospitalization: not having a stable affective relationship (i.e. being single, widowed or separated) was significant in both the univariate and the multivariate models, whereas living with the family of origin rather than alone was only significant in the univariate model. The absence of one's own family, which may reflect a difficulty in psychosocial adaptation, therefore worsens functional outcome regardless of the underlying illness. The greater probability of rehospitalization of patients living with their family of origin compared to those who live alone may reflect a greater attention to clinical conditions requiring hospitalization or less tolerance to even milder symptoms, thus leading the patients to be brought to the attention of psychiatric services.

There are published data indicating that the existence of stable interpersonal relationships with friends and relatives improves the quality of life and the prognosis of schizophrenia45,46. On the other hand, patients with a better course of the disorder and less associated complications (i.e. substance abuse, law violations) are also able to maintain a valid network of friends and relatives, resulting in a better social support than those who have a worse course and outcome of schizophrenia.

The other clinical and sociodemographic characteristics considered at the time of first hospitalization, the type of admission and the duration of hospitalization were not significantly associated with the risk of rehospitalization.

With regards to the third objective of the study, we found a high percentage of diagnostic stability in schizophrenic patients. Some published data indicate that diagnostic stability is greater in adult patients than in adolescents at the time of first admission; the mean age of our sample was 34 years47. A four-year follow-up study has found that the diagnosis of schizophrenia is more stable over time than the other psychoses48. The positive predictive value of a diagnosis of schizophrenia is reported to be more than 90%49.

Some limitations, however, must be considered when drawing inferences from the present data.

In our study we referred to routine clinical diagnoses as reported in the Discharge Register according to ICD-9-CM codes without using a structured diagnostic interview, and the clinical diagnosis is the primary diagnosis regardless of comorbidity. Moreover, evaluation of symptoms like anxiety or depression at the time of admission and of attempted suicides should be considered and based on specific instruments and scales. We considered an heterogeneous group of non schizophrenic psychoses including very different diagnoses such as dementia and organic psychoses, substance abuse and bipolar disorder, even if age and sex differences may have affected the distribution of some of the characteristics examined.

About patients' previous contacts with private psychiatrists or clinics we could only refer to our anamnesis records, which however include specific items regarding this kind of previous information.

In conclusion, in our sample, only some symptomatological characteristics (particularly the presence of at least one PANSS positive symptom at the time of first admission) and a positive history of previous psychiatric non psychotic episodes seem to be the most significant risk factors for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. This suggests that other more specific factors (such as biological factors) should be considered at the time of first admission to hospital. Schizophrenic patients are certainly at greater risk of rehospitalization, although the diagnosis itself seems to be less important than other variables.

References

1. Sartorius N, Jablensky A, Korten A, Ernberg G, Anker M, Cooper JE, et al. Early manifestation and first contact incidence of schizophrenia in different cultures. A preliminary report on the initial evalutation phase of WHO Collaborative study on determinants of outcome of severe mental disorders. Psychol Med 1986; 16(4): 909-928. [ Links ]

2. Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, Anker M, Korten A, Cooper JE. Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures: a World Health Organization ten - country study. Psychol Med Monogr (Suppl) 1992; 20: 1-97. [ Links ]

3. Rössler W, Salize HJ, Van Os J, Riecher-Rössler A. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2005; 15: 399-409. [ Links ]

4. Jablensky A. Schizophrenia: recent epidemiologic issues. Epidemiol Rev 1995; 17(1): 10-20. [ Links ]

5. Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, Kuoppasalmi K, Isometsä E, Pirkola S, et al. Lifetime Prevalence of Psychotic and Bipolar I Disorders in a General Population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64(1): 19-28. [ Links ]

6. Hafner H, Riecher-Rossler A, Maurer K, Fatkenheuer B, Loffler W. First onset and early symtomatology of schizophrenia. A Charter of epidemiological and neurobiological research into age and sex differences. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 242(2-3): 109-118. [ Links ]

7. Hafner H. Onset and early course as determinants of the further course of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2000; 407: 44-48. [ Links ]

8. Hafner H, Maurer K, Trendler G, An der Heiden W, Schmidt M. The early course of schizophrenia and depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 255(3): 167-173. [ Links ]

9. Marshall M, Lockwood A, Lewis S, Fiander M. Essential elements of an early intervention service for psychosis: the opinions of expert clinicians. BMC Psychiatry 2004; 4:17. [ Links ]

10. Young AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Bullettin 1996; 22 (2): 353-370. [ Links ]

11. An der Heiden W, Hafner H. The epidemiology of onset and course of schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neuro 2000; 250: 292-303. [ Links ]

12. Haas GL, Garratt LS, Sweeney JA. Delay to first antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: impact on symptomatology and clinical course of illness. J Psychiatr Res 1998; 32(3-4): 151-159. [ Links ]

13. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B et al. Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156(4): 501-503. [ Links ]

14. Malla AK, Norman RM, Manchanda R, Ahmed MR, Scholten D, Harricharan R et al. One year outcome in first episode psychosis. Influence of DUP and other predictors. Schizophrenia Res 2002; 54(3): 231-242. [ Links ]

15. Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Øhlenschlæger J, le Quach P et al. Five-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Multicenter Trial of Intensive Early Intervention vs Standard Treatment for Patients With a First Episode of Psychotic Illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65(7): 762-771. [ Links ]

16. Preti A, Miotto P. Increase in first admissions for schizophrenia and other major psychoses in Italy. Psychiatry Research 2000; 94: 139-152. [ Links ]

17. Piccinelli M, Politi P, Barale F. Focus on psychiatry in Italy. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 181: 538-544. [ Links ]

18. Zeppegno P, Airoldi P, Manzetti E, Panella M, Renna M, Torre E. Involuntary psychiatry admissions: a retrospective study of 460 cases. Eur J Psychiatry 2005; 19(3): 133-143. [ Links ]

19. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull 1987; 13: 261. [ Links ]

20. Kaplan EL, Meier P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457-481. [ Links ]

21. Greenwood M. The natural duration of cancer. Rep Pub Health Med Sub 1926; 33: 1-26. [ Links ]

22. Baldwin P, Browne D, Scully PJ, Quinn JF, Morgan MG, Kinsella A et al. Epidemiology of first-episode psychosis: illustrating the challenges across diagnostic boundaries through the Cavan-Monaghan study at 8 years. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31(3): 624-638. [ Links ]

23. Sham PC, MacLean CJ, Kendler KS. A typological model of schizophrenia based on age at onset, sex and familial morbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89(2): 135-141. [ Links ]

24. Häfner H, Maurer K, Löffler W, An der Heiden W, Munk-Jørgensen P, Hambrecht M et al. The ABC schizophrenia study: a preliminary overview of the results. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33: 380-386. [ Links ]

25. Suvisaari JM, Haukka J, Tanskanen A, Lönnqvist JK. Age at onset and outcome in schizophrenia are related to the degree of familial loading. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173: 494-500. [ Links ]

26. Suvisaari JM, Haukka JK, Tanskanen AJ, Lönnqvist JK. Decline in the Incidence of Schizophrenia in Finnish Cohorts Born From 1954 to 1965. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56: 733-740. [ Links ]

27. Haukka J, Suvisaari J, Lonnqvist J. Increasing age does not decrease risk of schizophrenia up to age 40. Schizophr Res 2003 May 1; 61(1): 105-110. [ Links ]

28. Bromet EJ, Jandorf L, Fennig S, Lavelle J, Kovasznay B, Ram R et al. The Suffolk County Mental Health Project: demographic, premorbid and clinical correlates of 6-month outcome. Psychol Med 1996; 26(5): 953-962. [ Links ]

29. Shatasel DL, Gue RE, Gallacher F, Heimberg C, Gur RC. Gender differences in the clinical expression of schizophrenia. Schizoph Res 1992; 7(3): 225-231. [ Links ]

30. Hafner H, Nowotny B. Epidemiology of early-onset schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 245(2): 80-92. [ Links ]

31. Hafner H, Maurer K, Trendler G, An der Heiden W, Schmid M, Konnecke R. Schizophrenia and depression: challenging the paradigm of two separate diseases-a controlled study of schizophrenia, depression and healthy controls. Schizophr Res 2005; 77(1): 11-24. [ Links ]

32. Haas GL, Garratt LS, Sweeney JA. Delay to first antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: impact on symptomatology and clinical course of illness. J Psychiatr Res 1998; 32(3-4): 151-159. [ Links ]

33. Craig TJ, Bromet EJ, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, Lavelle J, et al. Is there an association between duration of untreated psychosis and 24-month clinical outcome in a first-admission series? Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157(1): 60-66. [ Links ]

34. Keshavan MS, Haas G, Miewald J, Montrose DM, Reddy R, Schooler NR, et al. Prolonged untreated illness duration from prodromal onset predicts outcome in first episode psychoses. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29(4): 757-769. [ Links ]

35. Gelber EI, Kohler CG, Bilker WB, Gur RC, Brensinger C, Siegel SJ, et al. Symptom and demographic profiles in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2004; 67 (1): 185-194. [ Links ]

36. Cougnard A, Kalmi E, Desage A, Misdrahi D, Abalan F, Brun-Rousseau H, et al. Pathways to care of first-admitted subjects with psychosis in South-western France. Psychol Med 2004; 34(2): 267-276. [ Links ]

37. Preti A, Rucci P, Santone G, Picardi A, Miglio R, Bracco R et al. Patterns of admission to acute psychiatric in-patient facilities: a national survey in Italy. Psychol Med 2009; 39(3): 485-496. [ Links ]

38. Craig TJ, Bromet EJ, Jandorf L, Fenning S, Taneberg-Karant M., Ram R, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and six-month outcome status in first-admission psychosis. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1997 Jun; 9(2): 89-97. [ Links ]

39. Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C, Dazzan P, Morgan K, Tarrant J, et al. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AeSOP study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63(3): 250-258. [ Links ]

40. Scully PJ, Quinn JF, Morgan MG, Kinsella A, O'Callaghan E, Owens JM, et al. First-episode schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychoses in a rural Irish catchment area: incidence and gender in the Cavan-Monaghan study at 5 years. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2002; 43: s3-9. [ Links ]

41. Sanbrook M, Harris A. Origins of early intervention in first-episode psychosis. Australasian Psychiatry 2003; 11(2): 215- 219. [ Links ]

42. An der Heiden W, Hafner H. The epidemiology of onset and course of schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 250(6): 292-303. [ Links ]

43. Malla AK, Norman RM, Manchanda R, McLean TS, Harricharan R, Cortese L, et al. Status of patients with first-episode psychosis after one year of phase-specific community-oriented treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53 (4): 458-463. [ Links ]

44. Petersen L, Thorup A, Øqhlenschlaeger J, Christensen TØ, Jeppesen P, Krarup G, et al. Predictors of remission and recovery in a first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder sample: 2-year follow-up of the OPUS trial. Can J Psychiatry 2008; 53(10): 660-670. [ Links ]

45. Harvey CA, Jeffrwey SE, McNaught AS, Blizard RA, King MB. The Camden Schizophrenia Survey III: Five-year outcome of a sample of individuals from prevalence survey and the importance of social relationships. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2007, 53(4): 340-356. [ Links ]

46. Eack SM, Newhill CE, Anderson CM, Rotindi AJ. Quality of life for persons living with schizophrenia: more than just symptoms. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2007; 30(3): 219-222. [ Links ]

47. Menezes NM, Milovan E. First-episode psychosis: a comparative review of diagnostic evolution and predictive variables in adolescents versus adults. Can J Psychiatry 2000, 45(8): 710-716. [ Links ]

48. Whitty P, Clarke M, McTigue O, Browne S, Kamali M, Larkin C, et al. Diagnostic stability four years after a first episode of psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 2005; 56 (9): 1084-1088. [ Links ]

49. Bromet EJ, Naz B, Fochtmann LJ, Carlson GA, Taneberg-Karant M. Long-term diagnostic stability and outcome in recent first-episode cohort studies of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31 (3): 639-649. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Lisa Lavatelli

SCDU Psichiatria

ASO Maggiore della Carità

Corso Mazzini 18

28100 Novara, Italy

Tel. +39 0321 3733440

Fax 0321 3733121

E-mail: lisalavatelli@msn.com

Received 7 December 2008

Revised 20 April 2009

Accepted 8 May 2009