My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The European Journal of Psychiatry

Print version ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.23 n.4 Zaragoza Oct./Dec. 2009

Delusions of Pregnancy with Post-Partum Onset: An Integrated, Individualized View

Maria Simon; Viktor Vörös; Robert Herold; Sándor Fekete; Tamás Tényi

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Pécs, Medical School, Pécs. HUNGARY

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: Bizarre hypochondriacal delusion is an important content of delusion of pregnancy during post-partum period.

Methods: Here we report two cases with postpartum delusion of pregnancy; one with pre-existing schizophrenia and another one with family history of pseudocyesis and schizoaffective disorder but with no pre-existing psychiatric illness.

Results: Nosological, phenomenological and aetiological issues are discussed. In the context of novel deficit-and motivational theories of delusion formation we provide an integrated view of the reported cases.

Conclusions: The complexity of the delusion of pregnancy should be considered in the treatment planning-particularly in the post-partum period.

Key words: Delusion of pregnancy; Somatic delusions; Post-partum psychosis; Delusion formation.

Introduction

It is a relatively common false belief among non-pregnant women that they are pregnant1. These fantasies can appear recurrently, especially in women with unconscious conflicts, guilt and ambivalences about pregnancy. In some even rarer cases such beliefs of pregnancy are false ideas that cannot be corrected by reasoning and are thus delusional. Delusion of pregnancy should be distinguished from four additional conditions imitating pregnancy:

1. Pseudocyesis is a state when a non-pregnant woman has a false belief that she is pregnant and presents marked bodily sings of pregnancy (i.e. amenorrhea, breast changes, nausea, abdominal enlargement, foetal movements reported by the patient, weight gain, etc.). Pseudocyesis frequently occurs in hysterical women with infantile personalities and abnormal sexual histories2, but it can also appear in relation to infertility in women with normal sexual behaviour3. The false belief of pregnancy is not obligatory in pseudocyesis, however, bodily changes characteristic of pregnant state are always present4, 5. On the other end of the extreme, pseudocyesis can be delusional, when the false belief of pregnancy is firm and unshakable. Pseudocyesis and delusional pregnancy can be differentiated by absence or presence of somatic manifestations of the gravid state6.

2. Pseudopregnancy is a somatic state resembling pregnancy that is triggered by organic factors (e.g. physical symptoms caused by endocrine tumours).

3. Simulated pregnancy, when a woman admits to be pregnant, although she is aware that she is not7, 8.

4. Couvade syndrome, where the father develops a variety of somatic symptoms before, during or after the birth of the child. His behaviour can resemble that of pregnant women, although he knows that he is not pregnant9. Rarely, Couvade syndrome can be de-lu-sional as well10.

Delusion of pregnancy is a special form of hypochondriacal/ somatic delusion. It is nosologically non-specific, occurring in schizophrenia and schizo-affective disordere.g.11-14, in delusive disorderse.g.5-15, in affective disorderse.g.12, 16, 17, in epilepsy e.g.12, 18, 19, in dementia, and other organic brain syndromese.g.12, 18, 20, as well as in medical conditions like urinary tract infection21, drug-induced lactation22, and po-lydypsia and hyponatremia syndrome23.

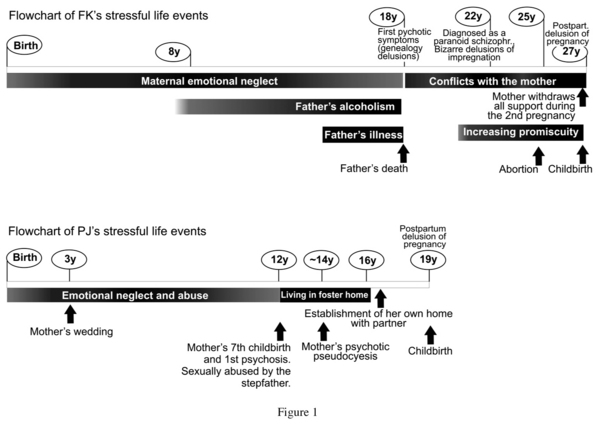

Historically, the first case involving delusional pregnancy was documented by Esquirol at the beginning of the 19th century24. Like in Esquirol's case report, a well-recognized setting of delusional pregnancy is that of erotomania: the 31-year-old woman thought to be pregnant by her famous professor, although she had never talked to him1. Since that early report, delusional pregnancies have been repeatedly described not only in women, but in men. Delusion of pregnancy in males12, 13, 16-20 is extremely bizarre, which explains their disproportionately frequent occurrence in the literature14. Some further unusual and odd cases have also been published: e.g. delusions of multiple pregnancies11, 12, recurrent delusion of pregnancy25, experience of labour and parturition21, puppy pregnancy in humans26, delusion of test-tube pregnancys27, widely shared delusion of pregnancy1, delusion of pregnancy in primary sterility28 and delusional pregnancy persisting over decades5, 14 Delusion of pregnancy, occurring during the post-partum period can also be considered as somatic/ hypochondriacal delusions with bizarre content. Here we report two cases with post-partum delusion of pregnancy. The flow-chart (Figure 1) demonstrates life events, psychosocial stressors and appearance of clinical symptoms in both cases.

Case reports

Case #1: P.J., a 19-year-old gipsy woman was referred with acute psychotic symptoms to the psychiatric clinic 8 days after she gave birth to a baby girl by uncomplicated, vaginal delivery. She had no history of mental illness. Since the age of 17 she has been cohabitating with her present partner. They lived in a traditional, rural gipsy area where childless couples were condemned.

Within two years she got pregnant. During pregnancy she was full of concerns about financial matters as well as seeing herself as a mother in the near future. Furthermore, she had enormous fears of the delivery, was also preoccupied with terrifying stories about deliveries with deadly outcome and did not take care of herself and her foetus (i.e. she did not consume healthy foods, did not cease to smoke, etc.).

By the 6th day after the delivery she developed behavioural alterations, became increasingly upset, neither slept nor ate, but walked naked in the garden at the night. She developed bizarre and grandiose delusions of postpartum pregnancies, talked to invisible people while she was fully neglecting her newborn. On admission she claimed to be pregnant even after the childbirth and reported numerous (at least 30) deliveries in the past two-three days. She did not know where her newborn babies were but she could hear them cry all the time. She felt "pulsations" in her abdomen, which she attributed to the movements and the heartbeat of additional unborn foetuses.

P.J. was born out of wedlock; she has never known who her father was. When she was 3 years old, her mother got married and gave birth to 4 additional children. P.J. had a peripheral position in this family, was emotionally and physically neglected and often witnessed her mother and step-father having intercourse. Immediately after the birth of her seventh child, the mother was admitted to the psychiatric hospital with acute psychotic symptoms. While the mother was treated in the hospital, the stepfather fondled the 12-year-old P.J. and masturbated in front of her. P.J. fled and took shelter with relatives, who reported the abuse to the Child Welfare. As a result she was placed in a foster home, where she stayed till the age of 16. Soon after leaving the foster home P.J. moved in with her boyfriend and maintained just superficial contact with her mother. The mother had several subsequent psychotic episodes. Most remarkably, the mother was admitted to our clinic with psychotic pseudocyesis five years before P.J.'s postpartum psychotic episode.

P.J. was diagnosed as having schizoaffective psychosis and was put on a combination of a mood stabilizer (lithium carbonate) and antipsychotics (first haloperidol later switched to olanzapine because of extrapyramidal side effects). Her psychotic symptoms gradually vanished: two weeks later she claimed to be pregnant with a male foetus, by the fourth week of her clinical treatment she did not experience "foetal movements" anymore and she presumed that the foetus had been absorbed. Shortly afterwards she was discharged to her home where the female members of the family looked after the baby during her stay in hospital and provided adequate support in the followings. After an asymptomatic year she discontinued the medication and was soon readmitted to the psychiatric clinic with schizoaffective psychosis (without delusion of pregnancy).

Case #2: F.K., a 27-year-old woman, diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic at the age of 22 was admitted to our inpatient service from the obstetrical clinic 4 days after a caesarean delivery (because of arrest of labour) in the 40th week of her first pregnancy. Simultaneously the baby was placed in a foster home for infants. After delivering a healthy male child, F.K. felt persistently pregnant that she supposed to be supported by physiological signs of the postpartum period (her abdomen was protruded, she felt tired, etc). She experienced pelvic and abdominal sensations that she attributed to foetal movements. At the same time she developed delusions of impregnation: she reported that in the 6th or 7th month of pregnancy she was narcotized by tranquilizers that had been put in her drink and was raped and fertilized while sleeping fast by men hired by her mother. She claimed that her second foetus remained in her belly after having delivered the first baby.

F.K. belongs to an urban family with low socio-economical status. Her father, an alcoholic, died of cancer when she was 18. F.K. could recall frequent and violent family arguments during her childhood. The relationship with her father was warmer than with the emotionally distanced mother. After losing her father F.K. declared that he was not her biological father -just a step-father-. Later she developed the delusion that her mother was "an evil woman who has just come to destroy her". On her first psychiatric admission (at the age of 22) she had bizarre paranoid-hallucinatory symptoms, she stated -among others- that her mother hired some "pseudo-midwives", who narcotized her, fertilized her by rape and removed the embryos by cutting and hacking her womb and vagina.

Two years later she had an existing pregnancy terminated under pressure from her mother. This event ultimately convinced her about the "falseness" of her mother. She became more and more promiscuous and believed that she would not get pregnant anyway, because her womb might be "so severely damaged". Unexpectedly she became pregnant -presumably by the man with whom she had an unstable but long-lasting sexual relationship-. F.K. was plea-sed with the pregnancy, but the potential father did not acknowledge the fatherhood. Her mother pointed out F.K.'s poor financial conditions, and pressed her to terminate the pregnancy. After that F.K.'s persecutory, genealogic and misidentificatory delusions flared up. On the 8 week of pregnancy she attacked her mother and superficially hurt her with scissors. Therefore F.K. had to be hospitalized, and needed to be medicated with 10 mg/ day of olanzapine for the rest of the pregnancy.

Being acutely psychotic, F.K. was not able to care adequately for the newborn. On admission to the psychiatry she reported bizarre persecutory and misidentificatory delusions beside delusion of pregnancy. Her delusional belief of pregnancy remained unshakable for several weeks. Since her mother refused to look after the baby, the Child Welfare decided to place him in a foster home for infants. Eight weeks after the delivery while combined antipsychotic medications (flupenthixol decanoate and clozapine) were continually administered most of F.K.'s delusions gradually disappeared, and -apart from some residual symptoms- her behaviour became conventional. Hence, she could be discharged from psychiatric hospital.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first description of delusional pregnancy occurring during the early post-partum period. Brockington29 reviewed symptoms of postpartum psychoses and found that the delusions embrace nearly the whole spectrum of pathological beliefs and ideas, although some are typically associated with the topic of childbirth (e.g. grandiose ideas about the genealogy of the baby, fantasies about a divine or evil baby, persecutory thoughts relating to changelings).

According to Manoj et al.27, delusions of pregnancy are aetiologically heterogeneous phenomena: they can be triggered purely by organic factors without psychodynamic background or they can develop as an adaptation to stress induced by organic (e.g. endocrine) and/ or psychological factors. Mo-reover, deficits of cognitive processing as well as the cultural environment can also influence the emergence of the delusion.

Neuroendocrine factors

In a reported case, delusion of pregnancy accompanied by disorientation occurred in association with postpartum thyroiditis 3 months after the delivery30. Furthermore, it is well documented that prolactin elevation associated with antipsychotic medication can induce delusions of pregnancy in female patients with pre-existing psychotic disorder, especially when significant ambivalence is related to the pregnancy22, 31, 32. Although no direct psychotogenic effects of prolactin are known, Ali et al.31 suggested that delusions of pregnancy reported during antipsychotic treatment might be directly associated with rising prolactin concentrations.

Both of our patients described above had normal thyroidal status, a normal EEG and had no signs of any medical or organic brain disease. The delusion of pregnancy was in none of them a consequence antipsychotic treatment. Being in the early post-partum period their prolactin level was physiologically elevated. After psychiatric admission, high doses of antipsychotic (and mood stabilizing) medication were administered, therefore breastfeeding was contraindicated, and patients were medicated for some weeks to assist ablactation.

Psychodynamic and psychosocial factors

Traditional psycho-analytic interpretations attributed wish-fulfilling and protective role to false beliefs. Pregnancy, which establishes an undisturbed union of the mother and her foetus, was supposed to eliminate loneliness and helplessness in a magical way that can serve as a basis for delusion formation33. Similarly, loss of love and loss of a loved object (or of fertility), acute loneliness and real/ imagined loss of relationship were hypothesized to activate a delusion of pregnancy on a wish-fulfilling manner34, 35. During the post-partum period, ambivalence about role as a mother seems to be a further underlying psychological factor. Difficulties with identification with their mothers, which can be a common source of ambivalence with the mother role and a cause of feeling abandoned and helpless as a new mother, were present in both of our cases. Both of them were neglected by their emotionally unavailable, cold and careless mothers, who did not protect them from neglect and/ or abuse. Nevertheless, past sexual abuse was found to directly predispose patients to develop delusional pregnancy36.

Socio-cultural factors are not negligible in understanding believes about pregnancy. Chowdhury et al.26 reported six unusual cases of delusional puppy pregnancy (five men and one woman) in rural West Bengal area. Detailed phenomenological analysis revealed the special cultural background of the delusions: there is a strong belief in particular region of India that a dog bite may evolve into a puppy pregnancy even in the human male.

In the Christian-culture pregnancy is regarded as a "blessed state" and it is surrounded with respect and acknowledgement, which may find its roots in the fertility cult of the archaic folks. The rural gipsies in Hungary represent an ethnic group which lives in segregation and under very poor conditions. They have preserved many aspects of their archaic matriarchal culture, where fertility strongly influences women's evaluation and appraisal, and where delivery is a magical and uncontrollable act. Our first case (P.J.) occurred in the context of this traditional, rural culture, where childless couples are condemned. Therefore the entire social environment exerted a strong pressure on her to have a baby as soon as possible. She was deeply concerned about her previous two abortions, feared of infertility and of not being able to meet her environment's requirements. During pregnancy, an old woman told her terrifying stories about deliveries with deadly outcome which increased her fears of and ambivalence against motherhood.

Cognitive models

Current neurocognitive models have va-luable contributions to the theories of delusion formation. Models explaining delusion formation have been classically ordered in two main categories, the deficit and the motivational37-39. Deficit models interpret delusions as a result of cognitive dysfunctions and perceptual abnormalities, while motivational theories view delusions as an effort to relief unbearable distress and disintegrating anxiety. One of the most widely accepted deficit model is the two-factor (or two-deficit) model established by Landgon and Coltheart40, here an anomalous sensory perception is the "first factor" (i.e. first deficit) in delusion formation, which -together with cognitive biases- influences the content of the upcoming delusion. However, an additional "second factor" is necessary to explain how unusual assumptions end up in full-blown delusions (i.e. how do patients go from experiencing some bodily signs of pregnancy in the post-partum period to the deep conviction of post-partum pregnancy). Involving both cognitive and sensory aspects, the two factor model seems to be an appropriate cognitive model for somatic delusions.

Nevertheless, rigorous cognitive models do not sufficiently explain the emergence and maintenance of delusions; the integration with motivational aspects can provide a more detailed and individualized view41. In a motivational perspective McKay et al.42 regard delusions as "sleights of mind" composed to reduce fears and distress and to maintain a better integrity. They suggest reconsidering the purely sensory "first factor" in the two-factor model and adding "defences, desires, and motivations" to it. According to that, motivational models can involve some features of the psychoanalytic tradition (e.g. the concept of defence and the potentially wish-fulfilling role of delusions).

An integrated view of the delusion formation

In line with the novel two-factor model anomalous perceptions can be regarded as a "first factor" in the delusion formation. Previously, several case studies underlined the role of bodily changes, and their perception as anomalous experience in the development of delusional pregnancy. Bodily chan-ges and sensations (e.g. intestinal dilatation43, recently increased body weight35, or urinary tract infection21) can all be associated with the emergence of delusional pregnancy. Both of our patients paid increased attention to bodily changes physiologically appear during the puerperium, and reported well-noticeable abdominal and pelvic sensations. They regarded these physical signs as anomalous, namely not as a part of the post-partum physiological changes. Sensory experiences together with cognitive biases typically present in those prone to psychosis reinforced the generation of false hypothesis of pregnancy. An error in probabilistic reasoning ("second factor") led to the delusion formation. Continued anomalous bodily experiences due to the postpartum period favoured maintenance of the delusion.

However, integration of motivational aspects can provide a more differentiated and individualized understanding. The stressful context generated by the experience of being a new mother as well as being possibly insufficient in this role can predispose further hypothesis generation. This could be further motivated by the need to extend the peaceful and passive unity with the foetus, to maintain the restitutive and protective effect of the pregnancy (in case one against the environment, in case two against the patient's mother). Delusion of pregnancy occurring in the post-partum period can be regarded as an attempt to extend the time of expectation in order to avoid confrontation with painful emotions evoked by experiencing the mother role. Taken together, factors that favour maintenance of these delusions include cognitive reinforcement mainly caused by the relief following the delusion formation and by some cultural traditions regarding pregnancy.

Clinical relevance

Nosologically most cases (90%) of post-partum psychoses fulfil diagnostic criteria for a mood disorder (with 40% showing mania)44, but other psychotic disorders, including schizophreniform, schizoaffective, delusive, as well as brief psychotic disorders are also diagnosed in the puerperium. Delusion of pregnancy occurring in the post-partum period is a delusion with bi-zarre content, and refers to schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder, and not to a delusive or affective one.

Case reports usually reveal demographic characteristics, describe response to treatment, and/ or suggest etiology45. Patients with delusional pregnancy have been reported to be more hostile and treatment resistant compared with matched controls35. Possible etiological factors in delusion of pregnancy are typically limited to neurophysiologic, endocrine and traditional psychodynamic factors. Given the growing evidence of cognitive and affective models of delusion formation, an integrated, individualized model of delusion of pregnancy can advantageously contextualize the phenomenology and course of the illness.

Furthermore, an integrated model of de-lusion formation can generate implications for planning therapeutic interventions. During the post-partum period, when therapy resistance can be particularly challenging, integrating cognitive or supportive psychotherapy can be of particular importance. Cognitive psychotherapy can focus on cognitive processing of sensory experiences, and can help patients to correct irrational beliefs and hypothesis. The supportive psychotherapy can address motivational aspects of the delusion formation, in order to help patients develop adequate skills to cope with the large amount of stress emerging in the postpartum period.

References

1. Brockington I. Motherhood and mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. p. 27-35. [ Links ]

2. Fried PH, Rakoff AE, Schopbach RR, Kaplan AJ. Pseudocyesis: A psychosomatic study in gynecology. JAMA 1951; 145: 1329-1335. [ Links ]

3. Ladipo OA. Pseudocyesis in infertile patients. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1979; 16: 427-429. [ Links ]

4. Cohen LM. A current perspective of pseudocyesis. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139: 1140-1144. [ Links ]

5. DePauw KW. Three thousand days of pregnancy. A case of monosymptomatic delusional pseudocyesis responding to pimozide. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157: 924-928. [ Links ]

6. Hardwick PJ, Fitzpatrick C. Fear, folie, and phantom pregnancy: Pseudocyesis in a fifteen-year-old girl. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 139: 558-560. [ Links ]

7. Dumont M. La fecondite malheureuse de la premiere feministe francaise, Olympe de Gouges. Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet 1989; 84: 63-66. [ Links ]

8. Underhill JW. Observations on pseudocyesis, and on pregnancy in its relation to capital punishment. Am J Obstet 1878; 11: 21-36. [ Links ]

9. Mayer C, Kapfhammer HP. Couvade-Syndrom, ein psychogenes Beschwerdebild am Übergang zur Vaterschaft. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 1993; 61: 354-360. [ Links ]

10. Tényi T, Trixler M, Jádi F. Psychotic couvade: 2 case reports. Psychopathology 1996; 29: 252-254. [ Links ]

11. Chengappa KNR, Steingard S, Brar JS, Keshavan MS. Delusion of pregnancy in men. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 155: 422-423. [ Links ]

12. Michael A, Joseph A, Pallen A. Delusions of pregnancy. Br J Psychiat 1994; 164: 244-264. [ Links ]

13. Adityanjee A. Delusions of pregnancy in males. Psychopathology 1995; 28: 307-311. [ Links ]

14. Kornischka J, Schneider F. Delusion of pregnancy. A case report and review of the literature. Psychoptahology 2003; 36: 276-278. [ Links ]

15. Bitton G, Thibaut F, Lefevre-Lesage I. Delusions of pregnancy in a man. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148: 811-812. [ Links ]

16. Miller LJ, Forcier K. Situational influence on the development of delusions of pregnancy in a man. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149(1): 140. [ Links ]

17. Camus V, Schmitt L, Foulon C, De Mendonca Lima CA, Wertheimer J. Pregnancy delusions in elderly depressed woman: A clinical feature of Cotard's syndrome. Int J Geriatr Psychiat 1995; 10: 1071-1073. [ Links ]

18. Chaturvedi SK. Delusions of pregnancy in men. Brit J Psychiatry 1989; 154: 716-718. [ Links ]

19. Tényi T, Herold R, Fekete S, Kovács A, Trixler M. Coexistence of delusions of pregnancy and infestation in a male. Psychopathology 2001; 34: 215-216. [ Links ]

20. Jenkins SB, Revita DM, Tousignant A. Delusions of child-birth and labour in a bachelor. Am J Psychiatry 1962; 118: 1048-1050. [ Links ]

21. Rajagopalan M, Varma SL. Urinary tract infection and delusion of pregnancy. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1997; 31: 775-776. [ Links ]

22. Cramer B. Delusion of pregnancy in a girl with drug-induced lactation. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 127: 960-963. [ Links ]

23. Shiwach RS, Dudley AF. Delusional pregnancy with polydipsia: A case report. J Psychosom Res 1997; 42(5): 477-480. [ Links ]

24. Vié J, Bobé J. Les idees delirantes de grossesse. L'Encephale 1932; 27: 468-502. [ Links ]

25. Radhakrishnan R, Satheeshkumar G, Chaturvedi SK. Recurrent delusions of pregnancy in a male. Psychopathology 1999; 32: 1-4. [ Links ]

26. Chowdhury AN, Mukherjee H, Ghosh KK, Chowdhury S. Puppy pregnancy in humans. a culture-bound disorder in rural West Bengal, India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2003; 49: 35-42. [ Links ]

27. Manoj PN, John JP, Gandhi A, Kewalramani M, Murthy P, Chaturvedi SK, et al. Delusion of test-tube pregnancy in a sexually abused girl. Psychopathology 2004; 37: 152-154. [ Links ]

28. Griengl H. Delusional pregnancy in a patient with primary sterility. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2000; 21: 57-59. [ Links ]

29. Brockington I. Motherhood and mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996, p. 206. [ Links ]

30. Bokhari R, Bhatara VS, Bandettini F, McMillin JM. Postpartum psychosis and postpartum thyroiditis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1998; 23: 643-650. [ Links ]

31. Ali JA, Desai KD, Ali LJ. Delusions of pregnancy associated with increased prolactin concentrations produced by antipsychotic treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2003; 6: 111-115. [ Links ]

32. Ahuja N, Vasudev K, Lloyd A. Hyperprolactinaemia and Delusion of Pregnancy. Psychopathology 2008; 41: 65-68. [ Links ]

33. Deutsch H. The Psychology of Women. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1945. [ Links ]

34. Shankar R. Delusions of pregnancy in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 159: 285-286. [ Links ]

35. Rosch DS, Sajatovic M, Sivec H. Behavioral characteristics in delusional pregnancy: a matched control study. Int J Psychiatry Med 2002; 32: 295-303. [ Links ]

36. Varma SL, Katsenos S. Delusion of pregnancy. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1999; 33: 118. [ Links ]

37. Winters KC, Neale JM. Delusions and delusional thinking in psychotics: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 1983; 3: 227-253. [ Links ]

38. Blaney PH. Paranoid conditions. In: Millon T & Blaney PH, eds. Oxford textbook of psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999; p. 339-361. [ Links ]

39. Bentall RP, Corcoran R, Howard R, Blackood N, Kindermann P. Persecutory delusions, a review and theoretical integration. Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21: 1143-1192. [ Links ]

40. Langdon R, Coltheart M. The cognitive neuropsychology of delusions. Mind and Language 2000; 15: 183-216. [ Links ]

41. McKay R, Langdon R, Coltheart M. Models of misbelief: Integrating motivational and deficit theories of delusions. Conscious Cogn 2007; 16(4): 932-941. [ Links ]

42. McKay R, Langdon R, Coltheart M. Sleights of mind: delusions, defenses and self-depiction. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 2005; 10: 305-326. [ Links ]

43. Bhattacharyya S, Chaturvedi SK. Metamorphosis of delusion of pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46: 561-562. [ Links ]

44. Chaudron LH, Pies RW. The relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64: 1284-1292. [ Links ]

45. Dunn J, Murphy MB, Fox KM. Diffuse pruritic lesions in a 37-year-old man after sleeping in an abandoned building. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1166-1172. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Tamas Tényi MD, Ph.D.

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy

University of Pécs

Medical School, Pécs, Rét utca 2

H-7623, Hungary

Phone: 36-72-535950

Fax: 36-72-535951

E-mail: tamas.tenyi@aok.pte.hu

Received: 18 December 2008

Revised: 4 August 2009

Accepted: 7 September 2009