My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The European Journal of Psychiatry

Print version ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.26 n.3 Zaragoza Jul./Sep. 2012

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632012000300001

Common mental health disorders in children and adolescents in primary care: A survey of knowledge, skills and attitudes among general practitioners in a newly developed European country

Kurt Buhagiar*; Joseph R. Cassar**

* Department of Mental Health Sciences, University College London Medical School, London. United Kingdom

** Department of Psychiatry, Mount Carmel Hospital, Malta.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: General Practitioners (GPs) are generally the first point of contact for children and adolescents with mental health problems. This study investigates the confidence, beliefs, and knowledge of GPs regarding common mental health problems in youngsters.

Methods: A self-designed questionnaire was distributed to nearly all registered GPs in a middle-income European country in order to address the aims of the study.

Results: Response rate was 58%. Many GPs reported relatively low confidence on a number of issues, including diagnosis (70.0%), initiating management (86.6%), assessing the child-caregiver relationship (72.0%) and the ability to distinguish between normal and pathological behavioural problems (75.1%). However, GPs showed greater inclination to conduct follow-up care after assessment by specialist services (53.5%). Few GPs considered psychosocial interventions to play a role in the treatment of anxiety disorders (18.5%), hyperkinetic disorders (24.2%), depression (22.9%) and disruptive behaviour disorders (18.5%) and this largely came from younger GPs (p < 0.001).

Conclusions: Confidence of GPs in the management of youngsters with mental health problems is generally low. They may require significant back-up from specialist services in the form of both training and clinical collaboration.

Key words: General practitioner; Child and adolescent mental health; Self-evaluation; Skills; Training.

Introduction

About 10% of children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 are estimated to be affected by behavioural and psychological problems that completely meet formal diagnostic criteria for mental disorders1. However, only a small minority of these youngsters are usually seen by secondary care specialist services2. This suggests that in most cases the responsibility for the diagnosis, management and follow-up is often taken by general practitioners (GPs)3. The latter are strategically placed to promptly identify emerging mental health problems in youngsters due to the nature of the relationship they can have with families4 and subsequently they can be play a major role in the provision of their clinical care3.

Nevertheless, specialised psychiatric skills may be required for the management of children and adolescents with mental disorders5. Psychiatric care delivery within primary care can also be limited by a number of factors, including limited support from primary care psychologists and social workers, excessive workloads of GPs6 and restricted training in child psychiatry7. It is indeed recognised that all professionals caring for youngsters require basic skills to identify and manage their psychological difficulties and to access specialised professionals when necessary8. Although children and adolescents with mental health problems presenting to GPs may not necessarily fulfil diagnostic criteria for mental disorders, these difficulties can be predictive of the future development of fully-fledged disorders9. Supporting the mental health of youngsters is therefore crucially important for the sound psychodevelopment of future generations.

However, detailed knowledge about the confidence and practices of GPs in working with children and adolescents with emotional and mental health problems remains somewhat sparse, compared to the knowledge available regarding similar practices with adults10. A few studies have been conducted that looked at specific mental disorders11. Others have included community paediatricians in their sample hence reducing the relevance and generalisability of the findings,5 some had a comparative approach as a main objective12,13 and others focused specifically on GPs practising in a rural setting14. Other studies adopting a broader perspective have all been conducted in countries with advanced economies, mostly in the US and Northern Europe7,10,15-17. It is recognised that developing and newly-developed countries are unable to match the capability and quality of primary care provision compared to their more developed counterparts18. The management of youngsters with mental disorders by GPs within less advanced economies, including emerging European countries, is therefore even less well known.

Aims and objectives

To partly address this shortcoming in knowledge, we conducted a cross-sectional survey amongst all GPs in Malta - a newly developed small island nation in the European Union. The objectives of this study were therefore to investigate how GPs evaluate their knowledge, skills and attitudes about the management of common mental disorders in children and adolescents.

Background to local setting

To put the study in perspective, primary care services in Malta are mainly delivered privately, with statutory-funded services only available as walk-in clinics, which are often unable to meet routine "non-urgent" presentations. On the other hand, privately-run services benefit from ubiquitous geographical availability, relative low financial cost and continuity of care akin to what can be expected in well-organised primary care services, such as health services in the UK. GPs in private care usually maintain comprehensive medical records similar and families usually have a specific GP they consistently present to. Youngsters under 16 years of age are invariably only seen by GPs as long as they are accompanied by their parents. In contrast, extensive secondary care services are largely delivered through public funding. However, secondary care child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) are limited and have long waiting lists for psychotherapeutic interventions, although this appears to be a universal phenomenon19. Middletier services providing a range of psychosocial care to children and adolescents are usually only available through both primary and secondary care, yet they have limited human resources. Adequate psychotherapeutic interventions are however available in private settings and can be accessed through primary care, but these may not lie within ordinary financial reach. Finally, collaboration between the various tiers of health care is uncommon.

Methods

Sample

The names and contact details of all GPs registered with the Family Practitioners' Register in Malta were formally obtained. A self-designed questionnaire was initially piloted with five trainees in general practice and two psychiatrists who gave their comments about structure, clarity and relevance of the questions. Due to limited funding, more formal evaluation and validation of the questionnaire was not possible. Following modification based on feedback received from piloting, it was sent to all 286 GPs in the register in a single wave in March 2008, accompanied by a cover letter which did not include specific instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. A return self-addressed envelope was also included, but no incentives of any kind were offered. A reminder and a duplicate survey package were posted after two months. The questionnaire was entirely anonymous, and had no coding system that would lead to retrospective tracking of respondents. Participant responses were thus only identified by sequential numbers in chronological order as they were received. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Malta research ethics committee.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of 3 parts, each presented on a separate page. The first page concerned demographic and general aspects of the respondents. GPs were also asked about the number of children and adolescents less than 16 years of age, including pre-school aged children presenting for the first time with mental health problems to their clinics every month. In our cover letter, we defined "mental health problems", as "any clinical presentation suggestive of difficulties in living, learning and relating, which is expressed in troublesome emotions and/or behaviours, as well as more explicit psychiatric disorders". Youngsters could be included regardless of whether these were the primary or secondary presenting problems.

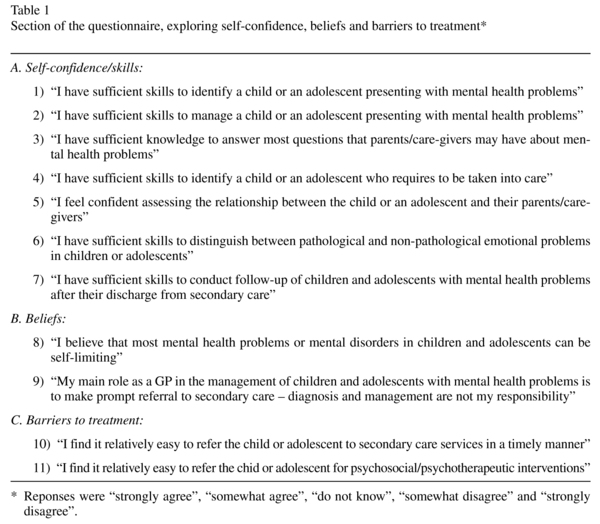

In the second page, inquiry about more specific issues pertinent to the aim of the survey was made. Firstly, GPs were asked about their general self-confidence, beliefs and barriers to treatment of children and adolescents. Measurement was made by a 5-point Likert anchored by: "strongly agree", "somewhat agree", "do not know", "somewhat disagree" and "strongly disagree". For statistical analysis, the terms "strongly agree" and "somewhat agree" were combined, and similarly for "strongly disagree" and "some-what disagree". Statements presented to GPs are listed in Table 1.

The final section explored more specific knowledge about the management of more explicit mental disorders, loosely based on ICD-1020 classification, namely: disruptive behaviour disorders, anxiety disorders, hyperkinetic disorders and depression. For each of these conditions, a choice of four therapeutic modalities ("antipsychotics", "antidepressants", "psychostimulants" and "psychosocial interventions") were presented. GPs had to choose either one or a combination of two options to denote the treatment they considered to be the most appropriate, whether recommended by them or by a psychiatrist.

Data analysis

Data were entered in duplicate in an electronic database by two independent assessors (KB and JC) and cross-checked at the end. SPSS version 14 for Windows was used for data analysis. Means, ranges and standard deviations for continuous and categorical variables are presented. Classified cross-tabulation and 2-tailed Chi-square tests were initially carried out as appropriate in order to evaluate GPs' responses with respect to demographic variables. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are quoted. Multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression was used to adjust for potential confounding demographic factors, namely age, years of clinical practice and gender, as guided by the initial unvariate analysis.

Results

Sample characteristics

We received 166 completed questionnaires (response rate = 58%). However, nine surveys were excluded from analysis due to substantial missing data. Therefore, there were 157 eligible respondents, whose characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Self-reported confidence, beliefs and barriers to treatment

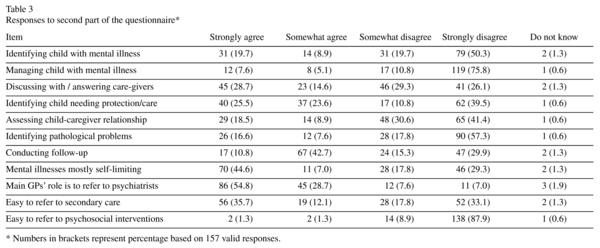

Responses to the questionnaire are summarised in Table 3. Of note is that may GPs reported low confidence in making a diagnosis (70.0%), initiating management (86.6%), assessing the child-caregiver relationship (72.0%) and distinguishing between normal and pathological behavioural problems (75.1%). Nevertheless, they encounter significant barriers when referring patients to secondary care specialist services (51.9%) and to psychosocial interventions (87.8%). Just over half of GPs believed that mental disorders in children and adolescents often resolve spontaneously.

Factors associated with confidence, beliefs and barriers to treatment

Analysis revealed correlations between demographic variables and some items of the questionnaire, as summarised in Table 4. GPs who had completed their medical training in the previous decade (p < 0.001; OR 14.4; 95% CI 2.3-4.8) and those who had attended continued medical education (CME) in general psychiatry (p = 0.002; OR 2.9; 95% CI 1.5-5.7) were more likely to have greater confidence discussing issues regarding mental disorders with the child's guardians. Years of clinical experience significantly confer confidence to conduct follow-up after discharge from secondary care CAMHS (p = 0.003; OR 3.0; 95% CI 1.5-6.1). Female GPs rated themselves better than males in assessing relationships with their caregivers (p < 0.05; OR 2.8; 95% CI 1.3-6.1) and identifying the need for custodial care (p < 0.001; OR 5.1; 95% CI 2.2-12.2). GPs with greater clinical experience (p = 0.003; OR 3.0; 95% CI 1.5-6.1) and those who did not participate in psychiatry-related CME (p < 0.001l; OR 9.3; 95% CI 4.5-19.7) showed a higher tendency to believe than mental disorders can be self-limiting. Significance levels unchanged after adjusting for confounding factors (age, gender, years of clinical experience) accordingly. Finally, Kendall tau rank correlation did not show a significant association between the number of patients seen by GPs per month and any of these items in the questionnaire.

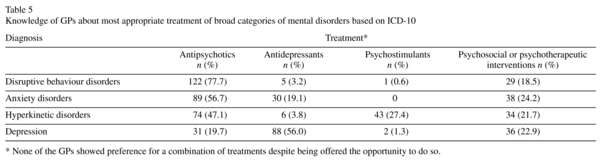

Knowledge about treatment

GPs were asked to select the therapeutic modality which they believed would be most appropriately instituted by themselves or child psychiatrists, either as stand-alone treatment or in combination. Results are summarised in Table 5.

None of the GPs opted for combination therapy of any kind. Only a minority of GPs (<25% in all diagnoses) considered psychosocial interventions to be the treatment of choice, and this largely came from younger GPs (p < 0.001 in all instances). There were no other factors influencing the choice of treatment for all diagnoses. The majority of GPs identified anti-psychotics as first-line treatment in disruptive behaviour/conduct disorders (77.7%), anxiety disorders (56.7%) and hyperkinetic disorders (47.1%).

Discussion

This study adds to the relatively sparse literature concerning GPs' attitudes to child and adolescent psychiatry. It is unique in having been conducted in a newly developed middle-income European country and with a study population that effectively represents more than half the entire national cohort of GPs.

Our questionnaire showed that on average two youngsters with new-onset mental health presentations are seen by GPs every month. It is clearly beyond the capability of the study to make any epidemiological extrapolations, but these self-reported data do provide a crude indication of the severity of this clinical presentation in the absence of any formally collated national data set.

In general, respondents were critical of their comfort in managing youngsters with mental health problems. Over two-thirds of GPs do not feel confident in making a diagnosis, initiate treatment, or able to differentiate understandable vagaries of childhood suffering from morbid states. Greater clinical experience, greater exposure to youngsters with mental health problems and participation in CME in psychiatry do not confer greater confidence in this respect. This may partly be related to the GPs' self-awareness of their level of knowledge of child psychiatry. Such unassuming approach adopted by GPs is however completely understandable when one considers that management decisions of this kind may carry life-long implications for the children and adolescents concerned.

Limitation of clinical skills is most likely not the sole contributory factor to this discomfort in GPs. Primary care frequently presents seriously challenging clinical and logistic situations4, including a lack of availability of fully-fledged multi-disciplinary teams, time constraints and overloaded clinics that negatively impact on the quality of care GPs could otherwise provide6. Therefore, GPs are aware that assessment and management of youngsters with emotional difficulties can be too strenuous and less effective in their clinics. Faced with these adversities, GPs may feel more inclined to refer youngsters immediately to specialist CAMHS were multi-disciplinary resources that can offer a holistic and more assertive approach are available. A qualitative study amongst inner London GPs about their attitudes towards adolescents presenting with depression showed that GPs often view this population of patients as differing in their qualities from adults, particularly with respect to their higher tendency to disengage from further follow-up appointments21. GPs may therefore perceive themselves to be in a vulnerable position while assessing youngsters and holding this notion in perspective, such that they may be reluctant to make clinically challenging decisions. Additionally, these London GPs expressed significant discomfort with making a diagnosis of depression in youngsters, and showed a tendency to challenge the validity of psychiatric diagnoses in this age group. These two attitudes held by GPs to adolescent mental health may therefore partly explain the increased likelihood of immediate referral to CAMHS reported by our respondents, as they may not necessarily feel comfortable making the initial decision-making themselves. On the other hand, it is encouraging that GPs in our study appear less intimidated by follow-up and maintenance treatment once specialist care has been involved as indicated by their responses.

Many of our respondents held the view that mental disorders in youngsters are often self-limiting. While, this may well be true in a proportion of children, there is also evidence that in a different sub-set of children and adolescents, mental disorders can be persistent and recurrent, contributing to a high degree of functional disability22. This tendency to "normalise" mental problems in youngsters is not unique amongst our respondents, having also been a dominant theme amongst London GPs21.

It is also acknowledged that accessing more specialist services represents a significant barrier for GPs. Scarcity of specialist CAMHS appears to be widespread even in highly advanced healthcare systems19 and GPs are likely to find themselves feeling responsible for burdening the saturated specialist services. Similar difficulties with accessing specialist CAMHS have also been expressed by Scottish GPs16. Access to local psychotherapeutic interventions is an even greater hurdle due to the limited number of qualified professionals within statutory CAMHS and the financial burden of accessing privately offered services. The latter would further add to the health inequalities in middle- and low-income countries given the increased prevalence of mental disorders in children of deprived families23. With the relative lack of confidence of GPs on the one hand, and the overall barriers to accessing secondary care CAMHS and psychotherapeutic interventions on the other hand, one wonders what happens to those youngsters who are possibly remaining bereft of immediate assessment and intervention. One would also fear that some youngsters may not be correctly identified as having a mental disorder as a result of the GPs' level of confidence. All of these factors highlight the importance for health systems in less advanced economies to deliver adequate care to young people with mental health problems given the public health concern arising from delayed or absent treatment.9 Stepped care, liaison and shared-care approaches with GPs could utilise resources more efficiently and enhance the confidence of GPs24.

In our study, female GPs were more confident than males in assessing child-guardian relationships and identifying youngsters needing to go into care. This may well be a reflection of women's greater sensitivity to the needs of youngsters.

Regarding the knowledge of GPs about treatment, there was great preference for pharmacological interventions. The potential role of combining pharmacological and psychosocial treatment was also greatly overlooked by GPs. Unfortunately, we did not enquire specifically about the GPs' actual clinical practice, although it is envisaged that such knowledge may also partly reflect itself in daily practice. A more encouraging finding is that less experienced GPs (hence likely of younger age) valued psychosocial interventions more highly than more experienced colleagues, probably reflecting newer trends in training. GPs are indeed aware of the difficulties they encounter in referring their young patients to psychosocial interventions. Faced with this discouraging scenario, GPs may have to rely on a culture that promotes a largely medicalised approach to mental disorders in primary care.

GPs also showed some underperformance with respect to their knowledge about psychotropic use in children and adolescents. In the absence of training and self-confidence in this field, it appears that GPs common prescribe medications in a way that most experts would consider to be inappropriate. While this may be viewed as a gap in knowledge, it is also recognised that doctors across all medical specialities are less likely to know management protocols developed by bodies of knowledge outside their own specialty25. It would therefore be valuable to highlight to GPs the importance of evidence-based practice and to make reference to guidelines such as those issued by the National Institutes of Health and Clinical Excellence in the UK.

GPs may need support to nurture greater confidence and increase their sensitivity to emotional issues in children and adolescents. This is particularly important given the high prevalence rates of youngsters presenting to primary care with mental health problems26,27. Amongst seven- to twelve-year old children presenting to primary care, 23% may be suffering from a mental disorder, many of whom are likely to initially present with a somatic complaint26. Amongst adolescents attending general practice, the prevalence of mental disorders increases to 38%, with the tendency for presentation with somatic complaints becoming even more pronounced27. Some GPs, particularly the more experienced sub-group of GPs who would have undertaken medical within the context of decades ago, should be encouraged to acquire greater awareness of the interplay between emotional, social and physical factors in the development of psychopathology. CME, including that delivered online, could potentially play a major role in fostering attitudinal change and increasing confidence15. Many GPs in our sample had not attended CME in psychiatry, but one postulates that little opportunities had been available in general. However, psychiatrists have an important role of taking initiatives to design and deliver educational programmes that target the needs of a non-specialist audience28. It has been shown that an educational intervention specifically developed to enhance the clinical qualities of GPs' who encounter adolescents presenting with potential mood disorders, resulted in greater rates of identification of the disorder by those GPs who had undergone this training29. Importantly, this intervention provided GPs with a psychosocial framework within which they could conceptualise and assess mental illness - a framework that the more experienced GPs in our sample may not necessarily be adopting. Similarly, a one-session educational intervention amongst GP trainees was shown to be effective in changing the trainees' attitudes, skills and knowledge with respect to child psychiatry such that at the end of training, they exhibited a lower threshold to identify mental disorders30. Finally, a brief training package for GPs, not only helped their recognition of mental disorders in children, but also improved their ability to involve parents in the child's psychiatric evaluation and management31.

Comparison with other studies

Similar low confidence levels in diagnosis and management of children and adolescents with mental problems has been reported by GPs in Scotland16 in the north of England10, in Finland7 and in a rural part of Canada14 on a wide range of issues in diagnosis and management of children and adolescents with psychiatric illness. GPs in South London were only able to detect one-fourth of children suffering from a mental disorder, and those who made the diagnosis planned to refer the children to CAMHS immediately17. Only one Canadian study showed that GPs had an intermediate level of confidence, and this improved with CME15. Unfortunately there is no similar data from other developing or newly developed European countries, which would have been particularly beneficial for comparative purposes.

Limitations

A number of limitations in our study should be acknowledged. Its main limitation arises from having been conducted in a small island nation, where medical training and health services are dictated by local intricacies. However, similar healthcare systems are likely to prevail in middle-income countries. Our response rate of 58% is modest, but GPs have been consistently reported to be a difficult group to survey32. Our questionnaire was only piloted among a small number of clinicians, and we were unable to ascertain its validity. The survey is entirely based on cross-sectional self-reported data, which may neither be entirely objective nor reflective of true clinical practices. As highlighted previously, it was not possible to determine how non-respondents differed from respondents due to the anonymous nature of the questionnaire, precluding any objective assessment of non-response bias. We have therefore not been able to determine not only the uniqueness of non-respondents in terms of their attitudes and how they would have responded to the questionnaire items, but also basic demographic information. Such nonresponse bias ultimately necessitates that our findings be interpreted with this perspective in mind. Further limitations arise from the nature of the survey design, including failure to enquire about confidence with respect to specific mental disorders and providing only a small number of generic therapeutic options on the items exploring knowledge of treatment. Enquiring about the actual clinical practice of GPs would have additionally added to the scientific value of our results.

Conclusions

Our findings may have implications for GP education, health services and public health, particularly within low-to-middle income countries. In our sample, GPs appear to have low levels of confidence on a wide range of factors related to the diagnosis and management of children and adolescent with mental health problems and disorders. Child psychiatrists need to take initiatives to tailor educational programmes aimed at filling training gaps and fostering greater confidence in GPs. Collaborative approaches between secondary care CAMHS and GPs, as well as enhanced access to psychotherapeutic interventions is likely to have major impact on the quality of treatment and subsequent health outcomes of youngsters.

References

1. Meltzer H, Gatward R, Goodman R, Ford T. The mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. London: Office for National Statistics; 2000. [ Links ]

2. Farmer E, Stangl DK, Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A. Use persistence and intensity: patterns of care for children's mental health across one year. Comm Ment Health J 1999; 5: 31-46. [ Links ]

3. Kramer T, Garralda E. Child and adolescent mental health problems in primary care. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2000; 6: 287-294. [ Links ]

4. Barbaresi W. Primary-care approach to the diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Mayo Clin Proc 1996; 71: 463-471. [ Links ]

5. Rushton JL, Clark SJ, Freed GL. Paediatrician and family physician prescription of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pediatr 2000; 105: E82. [ Links ]

6. Zantinge EM, Verhaak PFM, Bensing JM. The work-load of GPs: patients with psychological and somatic problems compared. Fam Pract 2005; 22: 293-297. [ Links ]

7. Heikkinen A, Puura K, Ala-Laurila EL, Niskanen T, Mattila K. Child psychiatric skills in primary healthcare - self-evaluation of Finnish health centre doctors. Child Care Health Dev 2002; 28: 131-137. [ Links ]

8. Ford T, Ramchandani P. Common mental health problems in childhood and adolescence: the broad and varied landscape. Child Care Health Dev 2009; 35: 751-753. [ Links ]

9. Taylor E, Chadwick O, Hepinstall E, Danckaerts M. Hyperactivity and conduct problems as risk factors for adolescent development. J Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35: 1213-1226. [ Links ]

10. Cockburn K, Bernard P. Child and adolescent mental health within primary care: a study of general practitioners' perception. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2004; 9: 21-24. [ Links ]

11. Shaw KA, Mitchell GK, Wagner IJ, Eastwood HL. Attitudes and practices of general practitioners in the diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Paediatr Child Health 2002; 38: 481-486. [ Links ]

12. DeBar L, Clarke GN, O'Connor E, Nichols GA. Treated prevalence, incidence, and pharmacotherapy of child and adolescent mood disorders in an HMO. Ment Health Serv Res 2001; 3: 73-89. [ Links ]

13. Harpaz-Rotem I, Rosenheck RA. Prescribing practices of psychiatrists and primary care physicians caring for children with mental illness. Child Care Health Dev 2005; 32: 225-237. [ Links ]

14. Steele M, Fisman S, Dickie G, Stretch N, Rourke J, Grindrod A. Assessing the need for and interest in a scholarship program in children's mental health for rural family physicians. Can J Rural Med 2003; 8: 163-170. [ Links ]

15. Miller AR, Johnston C, Klassen AF, Fine S, Papsdor M. Family physicians' involvement and self-reported comfort and skill in care of children with behavioral and emotional problems: a population-based survey. BMC Fam Pract 2005; 6: 12. [ Links ]

16. Bryce G, Gordon J. Managing child and adolescent mental health problems: the views of general practitioners. Health Bulletin (Edinb) 2000; 58: 224-226. [ Links ]

17. Sayal K, Taylor E. Detection of child mental health disorders by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 2004; 54: 348-352. [ Links ]

18. Reerink RH, Sauerborn R. Quality of primary healthcare in developing countries. Int J Qual Healthcare 1996; 8: 131-139. [ Links ]

19. Connor DF, McLaughlin TJ, Jeffers-Terry M, O'Brien WH, Stille CJ, Young LM, et al. Targeted child psychiatric services: a new model of pediatric primary clinician - child psychiatry collaborative care. Clin Pediatr 2006; 45: 423-434. [ Links ]

20. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [ Links ]

21. Iliffe S, Williams G, Fernandez V, Vila M, Kramer T, Gledhill J, et al. General practitioners' understanding of depression in young people: qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2008; 9: 269-279. [ Links ]

22. Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rhode P. Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 33: 809-818. [ Links ]

23. MacLeod JD, Shanahan MJ. Trajectories of poverty and children's mental health. J Health Soc Behav 1986; 37: 207-220. [ Links ]

24. Katon W, Russo J, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Bush T, et al. Long-term effects of collaborative care intervention in persistently depressed primary care patients. J Gen Int Med 2002; 17: 741-748. [ Links ]

25. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PAC, et al. Why don't physicians follow practice guidelines: does it really matter? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999; 282: 1458-1465. [ Links ]

26. Garralda ME, Bailey D. Children with psychiatric disorders in primary care. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1986; 27: 611-624. [ Links ]

27. Kramer T, Garralda ME. Psychiatric disorders in adolescents in primary care. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173: 508-513. [ Links ]

28. Hodges B, Inch C, Silver I. Improving the psychiatric knowledge, skills, and attitudes of primary care physicians, 1995-2000: A review. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1579-1586. [ Links ]

29. Gledhill J, Kramer T, Iliffe S, Garralda ME. Training general practitioners in the identification and management of adolescent depression within the consultation: a feasibility study. J Adolesc 2003; 26: 245-250. [ Links ]

30. Bernard P, Garralda ME, Hughes T, Tylee A. Evaluation of a teaching package in adolescent psychiatry for general practitioner registrars. Educ Gen Pract 1999; 10: 21-28. [ Links ]

31. Luk ESL, Brann P, Surtherland S, Mildred H, Birleson P. Training general practitioners in the assessment of childhood mental health problems. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002; 7(4): 571-579. [ Links ]

32. Thomson CE, Paterson-Brown S, Russell D, McCaldin D, Russell IT. Encouraging GPs to complete postal questionnaires - one big prize or many small prizes? A randomized controlled trial. Fam Pract 2004; 21: 697-698. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kurt Buhagiar

Department of Mental Health Sciences

University College London Medical School

Rowland Hill Street, London NW3 2PF, UK

Tel: +44 (0)20 7472 6168

Fax: +44 (0)20 7830 2808

E-mail: k.buhagiar@ucl.ac.uk

Received: 1 April 2011

Revised: 19 March 2012

Accepted: 27 March 2012