Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.26 no.3 Zaragoza jul./sep. 2012

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632012000300006

Burnout, occupational stressors, and social support in psychiatric and medical trainees

Antigonos Sochos, PhD*; Alexis Bowers, MRCPsych MSc**

* Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychology, University of Bedfordshire, Park Square, Luton. United Kingdom

** Consultant in Adult Psychiatry, Albany Lodge, Church Crescent, St Albans Herts. United Kingdom

Dirección para correspondencia

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: Although previous research reports that psychiatrists experience greater work-related distress than other specialties, very little is known about how psychiatric trainees compare to their medical colleagues. The aim of this study was to compare psychiatric and general medical trainees in burnout, work stressors, and social support and investigate potential buffering effects of social support.

Methods: This cross-sectional study included 112 psychiatric and 72 general medical trainees, based in the UK. Participants completed three questionnaires on-line: Maslach Burnout Inventory, Specialist Doctors´ Stress Inventory, and Social Support Scale.

Results: According to the findings, psychiatric trainees reported less burnout, fewer time demands, more consultant and emotional support but less family support than general medical trainees. In addition, social support moderated the effects of specialty on burnout, as it substantially reduced depersonalisation in medical but not in psychiatric trainees.

Conclusions: Findings may reflect recent changes in psychiatric training in the UK. Factors contributing specifically to medical trainees´ burnout and factors potentially preventing psychiatric trainees from utilising social support need to be explored in future research. The cross-sectional design and the low response rate were the main limitations of the study.

Key words: Burnout; Occupational stressors; Social support; Moderation effects; Psychiatric trainees; Medical trainees.

Introduction

Previous research suggests that, compared to other medical specialties, psychiatrists suffer from higher rates of psychological distress. Psychiatrists have reported higher levels of depression1 misuse of licit and illicit substances2, personal or family psychiatric history3, and negative personality attributes like neuroticism, agreeableness, and lack of conscientiousness1. Studies also suggest that psychiatrists experience higher work-related distress4. In the UK, psychiatrists of various seniority levels seem to experience higher work-related emotional exhaustion than their general medical or surgical colleagues, although they report fewer clinical work demands1. In addition, over one fifth of consultant psychiatrists working with the elderly scored at the highest brackets of burnout5. Nonetheless, most previous studies comparing burnout levels across medical specialties have recruited either consultants or doctors of varied clinical experience, neglecting trainees. This gap in the literature may be important as it has been suggested that patterns of psychological distress in doctors may be established very early in their careers6. Moreover, research reports that junior psychiatrists experience greater work-related distress than senior psychiatrists7, suggesting that this may be a particularly vulnerable group.

Research has identified various factors contributing to distress among psychiatrists; these could be distinguished into personal predispositions and external stressors. Like other mental health professionals, psychiatrists seem more likely to have experienced early abuse and trauma than the rest of health workers8, which may predispose them to ineffective coping strategies and an increased vulnerability to psychological distress. On the other hand, the psychiatric workplace is afflicted by external occupational stressors. Psychiatrists often work with threatening patients in isolation, experience violence and patient suicide, need to make critical decisions within multidisciplinary teams with unclear role definitions, and have to predict the risk of loss of life or serious injury when discharging difficult patients9. A recent study also lists long working hours, an aggressive administrative environment, and low pay as major correlates of emotional exhaustion among psychiatrists10. An important consequence of the above conditions seem to be the recent crisis in the recruitment and retention of psychiatrists, both in the UK and abroad11,12. In the UK psychiatrists who had retired early reported significant dissatisfaction with how psychiatry was conducted in the country while trainees identified inadequate sourcing, understaffing, and excess bureaucracy as the three major difficulties in the quality and safety of psychiatric practice13. However, a latest study evaluating changes introduced in UK psychiatry in the past decade found that training demands, rapid changes in the NHS, working across interfaces, and work-life balance are currently psychiatrists' major difficulties14.

Moreover, research has identified protective factors that can buffer or moderate the negative effects of occupational stressors. Although participation in recreational activities and taking time off on a holiday have been found to make a difference, a crucial protective factor against burnout may be social support. Support from colleagues, peers, and loved ones has been reported to protect psychiatrists as well as other health professionals from burnout15. However, empirical evidence backing the buffering role of social support is conflicting, as studies have also reported either no or limited moderating effects in relation to both occupational and non-occupational stressors16,17. Inconsistent conceptualisation and the use of ambiguous composite scores to measure social support are discussed by these authors as the most likely causes of this contradiction18.

Present study had three aims. The first aim was to fill the gap of the literature on junior doctors by comparing psychiatric and general medical trainees on burnout. The second aim was to compare psychiatric and general medical trainees on four types of occupational stressors: clinical responsibility, demands on time, organisational constraints, and personal confidence. Finally, our third aim was to compare psychiatric and general medical trainees on social support and investigate whether social support would protect junior doctors from burnout. Instead of using a global index of social support, we decided to measure six different types separately: instrumental, emotional, support from consultants, from coworkers, from management, and from family. To our knowledge no previous study has compared different specialties of medical trainees in separately measured types of social support.

To address the above aims, we formulated the following hypotheses on the basis of previous research:

a. Firstly, we expected psychiatric trainees to suffer greater burnout than general medical trainees.

b. Secondly, we hypothesised that psychiatric trainees would score lower than general medical trainees in clinical responsibility and personal confidence, but the two groups would not differ on the other two types of occupation stressor - demands on time, and organisational constraints.

c. We assumed that consultant psychiatrists would be more skilled in support provision than their medical counterparts and, as a result, we hypothesised that psychiatric trainees would perceive more social support from their consultants. On the other hand, as we assumed higher levels of general distress and lower capacity for support provision among junior psychiatrists, we expected psychiatric trainees to experience less co-worker and general emotional support than their medical counterparts. We also expected psychiatric trainees to perceive less support from their families than medical trainees.

d. Finally, we hypothesised that social support would moderate the effects of specialty on the two main aspects of burnout - emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. We thought that the variable specialty would encompass all personal and occupational, internal and external distress predisposing factors that may differentiate psychiatrists from other medical doctors, so we wanted to confirm that the effects of this all-inclusive variable on burnout would be buffered by the various types of social support.

Method

Participants and Design

The sample comprised 184 core junior doctors based in London, UK, 112 psychiatric and 72 general medical. Questionnaires were sent to all 1195 junior doctors (540 psychiatric, 654 medical) registered in a training post within the London Deanery in the particular year. Response rates were 20.7 for psychiatrists, 11% for general medical, and 15.4% for the whole sample. A cross-sectional questionnaire-based design was employed measuring four types of occupational stressor, six types of social support, and three aspects of burnout.

Materials

The following self-report questionnaires were used on an online format:

Socio-demographic Questionnaire: Participants were also asked to provide information on gender, age, marital status, ethnicity, number of years in medicine, and medical specialty.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)19. This 22-item questionnaire uses a 7-point Likert scale to measure 3 burnout dimensions (Emotional Expression, Depersonalisation, Personal Accomplishment). As the authors report good reliability and validity, this instrument has been used in a variety of studies involving health professionals20. In the current study Cronbach α was 0.91 for EE, 0.79 for DP, and 0.77 for PA.

Specialist Doctors' Stress Inventory (SDSI)21. This 25-item questionnaire uses a 7-point Likert scale to measure four types of occupational stressors (Clinical Responsibility, Demands on Time, Organisational Constraints, Lack of Personal Confidence). The questionnaire has been validated against the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Neuroticism scale of the NEO-Five Factor Inventory and measures of work satisfaction and quality of life1,22. In the present study, Cronbach α was 0.72 for CR, 0.67 for DT, 0.82 for OC, and 0.75 for PC.

Social Support Scale (SSS)23. This 24-item questionnaire uses a five-point Likert scale to measure the perception of two types of social support (instrumental, emotional) from four sources (family, consultant, co-worker, senior management). Research with health and social care workers has supported the scale reliability and validity of the questionnaire24. Cronbach α in the current study was 0.78 for Instrumental, 0.72 for Emotional, 0.92 for Family, 0.95 for Consultant, 0.89 for Coworker and 0.93 for Senior Management support.

Procedure

Questionnaires in an online format were sent to participants via email. The attached hyperlink directed participants to a custom made website that allowed them to provide informed consent and complete the questionnaires anonymously. The research proposal received ethical approval from the ethics committees of the University of Bedfordshire, the local NHS, the West London Mental Health Research and Development Consortium, and the London Deanery.

Data Analysis

To address the first three hypotheses we used multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and to address the fourth hypothesis we used moderated regression analysis.

Results

Sixty percent of the participants were female and 68% were married (mean age of whole sample = 30.6, sd = 4.4). The mean time since obtaining a medical degree was 1.48 years, sd = 0.63 (M = 1.13, sd = 0.35 for medical and M = 1.71, sd = 0.68 for psychiatric trainees).

Skewness and kurtosis statistics for study variables ranged from -0.62 to 1.71 and -0.83 to 0.72 respectively (kurtosis for management social support was 2.80), suggesting no major deviations from normality. Firstly, we compared the two specialty groups in terms of demographic and other background variables, so that we controlled for potential differences in group comparisons involving the study variables (occupational stressors, social support, and burnout); we found that general medical trainees were younger (t = 8.81, p < 0.001), more recently qualified (t = 7.57, p < 0.001, df = 182), more often single (χ2 = 7.17, p = 0.007, df = 1) and female (χ2 = 5.46, p = 0.019, df = 1). As each background variable was related with at least a few study variables, we decided to control for these background variables in the MANOVA analyses.

To address our first three hypotheses, we conducted four MANOVAs, with specialty as the independent variable and the following blocks of dependent variables each time: the three aspects of burnout, the four work-related stressors, the four sources of social support, and the two overall types of social support, instrumental and emotional (Table 2). Results indicated that, compared to psychiatric trainees, medical trainees experienced higher burnout and a larger number of general medical trainees scored at the top bracket of emotional exhaustion (58 vs. 32 trainees, χ2 = 12.52, p = 0.002) and depersonalisation (64 vs. 30 trainees, χ2 = 28.16, p < 0.001) scales. In addition, medical trainees experienced greater time pressure and lower emotional and consultant support, while psychiatric trainees reported lower levels of family support. The two specialties did not differ in relation to any other work stressor or type of support.

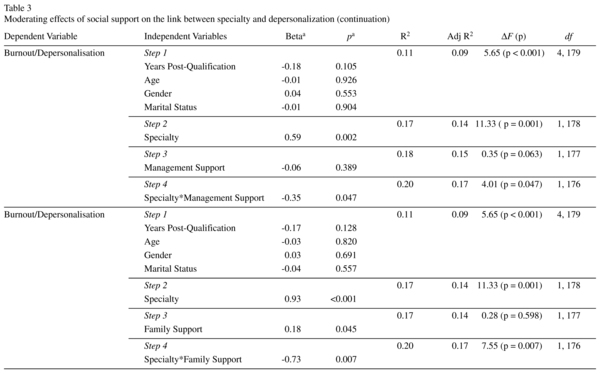

To address our last hypothesis, we conducted a series of moderated regression analyses using specialty group as the independent variable, either emotional exhaustion or depersonalization as the dependent variable, and one of the six types of social support as the moderating variable each time (in total, twelve analyses were conducted). Age, gender, marital status, and post-qualification experience were controlled for (Table 3). Analyses suggested that four types of social support moderated the effects of specialty group on depersonalisation: instrumental, emotional, management, and family support. In particular, while these support resources did not substantially reduce the level of depersonalisation psychiatric trainees experienced, they did do so for medical trainees.

Discussion

Contrary to our hypotheses, general medical trainees reported more burnout and greater time demands than psychiatric trainees, while the groups did not differ on clinical responsibility, personal confidence, and organisational constrains. Confirming our expectations, psychiatric trainees perceived their consultants as more supportive and their families as less supportive than general medical trainees, while the former also reported higher emotional support. Finally, instrumental, emotional, management, and family support moderated the effects of specialty on depersonalisation.

Present findings should be approached with caution, due to the study's low response rate and correlational design. Low response rate was the most serious, as the study followed a similar recent trend in physician surveys, particularly on-line. Despite their convenience and cost-effectiveness, online questionnaires for medical practitioners often seem to end up at the bottom of very busy in-trays, particularly if the topic is not among doctors' priorities25. Those questionnaires require computer access, such as in the busy workplace where other matters are urgent. As reminder emails do not appear effective, paper based questionnaires may be the best options at the moment; they can be completed during a break or outside the workplace. However, this is expected to change, particularly among younger practitioners, due to internet dominance. It is possible that present low response may have introduced non-response bias, as respondents may have been among the most distressed medical trainees or/and the least distressed psychiatric. Nonetheless, burnout means and standard deviations, as well as bracket percentages in the whole and the psychiatric samples were very similar to those reported in the literature19,26; the figures for general medical trainees were slightly higher than usual, but only by less than half a standard deviation.

Present findings seem to contradict previous studies suggesting that psychiatrists experience higher work-related distress4. Although, as suggested above, this may have been the result of non-response bias, alternative explanations are also possible. Only one previous study exclusively compared trainee groups, using small samples with very dissimilar response rates and finding no differences27. It is possible that present findings reflect recent improvements in psychiatric training in the UK28. Such changes have included an increase in consultant posts, an increase in consultant time allocated in the most unwell patients and the related trainee supervision, the creation of functional teams, and changes in the Mental Health Act making appeals against civil sections less likely.

The greater perception of consultant support among psychiatric trainees appears consistent with a recent emphasis on social support at work in UK psychiatry, while the perception of lower family support may reflect more frequent distress in psychiatrists' families due to mental illness, perhaps imposing limitations on how these families support their healthier members3. Finally depersonalisation was the only aspect of burnout reduced by the presence of social support, while medical trainees were the only group to benefit from it. It is possible that factors specific to psychiatric work not addressed by recent changes, dysfunctional behavioural patterns of psychiatrists themselves or a combination of these, do not allow the utilisation of social support by trainees.

To the best of our knowledge this study is the first to comprehensively compare psychiatric and general medical trainees in aspects of work-related stress. Without overlooking the study's limitations, present findings may contribute to our understanding of current challenges faced by junior doctors. Findings suggest that the supportive role of consultants should be emphasised in psychiatric training and more resources need to be allocated towards the expansion of that role. Although in current study junior psychiatrists experienced more consultant support than medical trainees, such support was not protective against burnout, so future research should explore why this may be the case. The consultant-trainee relationship may be an important factor, so the contributions of the two parties need to be investigated (e.g. consultant accessibility, consultant empathy, trainee compliance with supervision, trainee support seeking). Training programmes also need to take into account trainee support resources outside the workplace. The relatively low support junior psychiatrists seem to perceive from their families may need to be considered in how the provision of workplace support is organised. Perhaps a more personal and emotional element should be integrated into the provision of consultant support.

Training programs in general medicine could build on the effectiveness of support resources utilised by the trainees and enrich the role of consultants as well as that of managers, as the latter seemed to have a protective effect. Perhaps the role of social support in combating occupational stress needs to be made clearer in trainees of any specialty and workshops developing their support utilising capabilities should be developed for those who need them. Future research should explore factors contributing specifically to medical trainees' burnout and factors rendering support resources for psychiatric trainees ineffective. Similar studies need also to be conducted in other countries so that potential national and cultural variations in medical training are identified.

References

1. Deary I, Agius R, Sadler A. Personality and stress in consultant psychiatrists. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1996; 42: 112-123. [ Links ]

2. Myers T, Weiss E. Substance use by internes and residents: an analysis of personal, social and professional differences. Br J Addiction 1987; 10: 1091-1099. [ Links ]

3. Frank E, Boswell L, Dickstein L, Chapman D. Characteristics of female psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 158: 205-212. [ Links ]

4. Kumar S, Hatcher S, Huggard P. Burnout in psychiatrists: an etiological model. Int J Psychiatry Med 2005; 35: 405-416. [ Links ]

5. Benbow S, Jolley J. Burnout and stress amongst old age psychiatrists. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17: 710-714. [ Links ]

6. Firth-Cozens J, Payne R. The psychological problems of doctors. In: Firth-Cozens J, Payne R, editors. Stress in health professionals: psychological and organizational causes and interventions. London: Wiley; 1999. p. 12-26. [ Links ]

7. Guthrie E, Tattan T, Williams E, Williams E, Black D, Bacliocotti H. Sources of stress, psychological distress and burnout in psychiatrists. Comparison of junior doctors, senior registrars and consultants. Psychiatr Bull 1999; 23: 207-212. [ Links ]

8. Elliot D, Guy J. Mental health versus non-mental health professionals: Child trauma and adult functioning. Professional Psychology: Theory and Practice 1993; 24: 83-90. [ Links ]

9. Firth-Cozens J. Improving the health of psychiatrists. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2007; 13: 161-168. [ Links ]

10. Kumar S, Hatcher S, Dutu G, Fischer J, Ma'u E. Stresses experienced by psychiatrists and their role in burnout: A national follow-up study. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2011; 57: 166-179. [ Links ]

11. Wilson R, Corby C, Atkins M, Marston G. Trainee views on active problems and issues in UK psychiatry: Collegiate Trainees' Committee survey of three UK training regions. Psychiatr Bull 2000; 24: 336-338. [ Links ]

12. Llewellyn A. Evidenced Based Recruitment in Psychiatry, the Missing Link - Prevocational Trainees. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2007; 41(Supp 1): A46-A47. [ Links ]

13. Kendell R, Pearce A. Consultant psychiatrists who retired prematurely in 1995 and 1996. Psychatr Bull 1997; 21: 741-745. [ Links ]

14. Rathod S, Mistry M, Ibbotson B, Kingdon D. Stress in psychiatrists: coping with a decade of rapid change. The Psychiatrist 2011; 35: 130-134. [ Links ]

15. Dallender J, Nolan P, Soares J, Thomsen S, Arnetz B. A comparative study of the perceptions of British mental health nurses and psychiatrists of their work environment. J Adv Nurs 1999; 29: 36-43. [ Links ]

16. Fenlason K, Beehr T. Social support and occupational stress: Effects of talking to others. J Organ Behav 1994; 15: 157-175. [ Links ]

17. Holmbeck G. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65: 599-601. [ Links ]

18. Hutchison C. Social support: factors to consider when designing studies that measure social support. J Adv Nurs 1999; 29: 1520-1526. [ Links ]

19. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual (3rd ed.). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [ Links ]

20. Truzzi A, Souza W, Bucasio E, Berger W, Figueira I, Engelhardt E, et al. Burnout in a sample of Alzheimer's disease caregivers in Brazil. Eur J Psychiat 2008; 22: 151-160. [ Links ]

21. Agius R, Blenkin H, Deary I, Zealley H, Wood R. Survey of Perceived Stress and Work Demands of Consultant Doctors. Occup Environ Med 1996; 53: 217-224. [ Links ]

22. Deary I, Blenkin H. Models of job-related stress and personal achievement among consultant doctors. Br J Psychol 1996; 87: 3-29. [ Links ]

23. House J, Wells J. Occupational stress, social support, and health. In: McLean A., Black G, Colligan M, editors. Reducing Occupational Stress: Proceedings of a Conference (Publication 78-140). Washington, DC: National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety; 1978. p. 8-29. [ Links ]

24. Jenkins R, Elliot P. Stressors, burnout and social support: Nurses in acute mental health settings. J Adv Nurs 2004; 48: 622-631. [ Links ]

25. Aitken C, Power R, Dwyer R. A very low response rate in an on-line survey of medical practitioners. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008; 32: 288-289. [ Links ]

26. Peisah C, Latif E, Wilhelm K, Williams B. Secrets to psychological success: Why older doctors might have lower psychological distress and burnout than younger doctors. Aging & Mental Health. 2009; 13: 300-307. [ Links ]

27. Martini S, Arfken C, Churchill A, Balon R. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry 2004; 28: 240-242. [ Links ]

28. Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (2009). National Survey of Trainees 2009. Retrieved March 2, 2010 http://reports.pmetb.org.uk/GroupCluster.aspx?agg=AGG27|2009 [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Antigonos Sochos, PhD

Departament of Psychology

University of Bedfordshire

Park Square

Luton LU1 3JU

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0) 1234 400400 (switchboard) ext 2037

F: +44 (0) 1582 489212

E-mail: antigonos.sochos@beds.ac.uk

Received: 20 September 2011

Revised: 21 March 2012

Accepted: 27 March 2012