My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

The European Journal of Psychiatry

Print version ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.27 n.1 Zaragoza Jan./Mar. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632013000100002

Subtyping demoralization in the medically ill by cluster analysis

Chiara Rafanelli, MD, PhD*; Jenny Guidi, PhD*; Sara Gostoli, PhD*; Elena Tomba, PhD*; Piero Porcelli, PhD** and Silvana Grandi, MD*

*Laboratory of Psychosomatics and Clinimetrics, Department of Psychology, University of Bologna, Bologna. Italy

**IRCCS De Bellis Hospital, Department of Gastroenterology, Psychosomatic Unit, Castellana Grotte. Italy

This study was supported in part by a grant from Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino, Italy, to Dr. Chiara Rafanelli.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: There is increasing interest in the issue of demoralization, particularly in the setting of medical disease. The aim of this investigation was to use both DSM-IV comorbidity and the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR) in order to characterize demoralization in the medically ill.

Methods: 1700 patients were recruited from 8 medical centers in the Italian Health System and 1560 agreed to participate. They all underwent a cross-sectional assessment with DSM-IV and DCPR structured interviews. 373 patients (23.9%) received a diagnosis of demoralization. Data were submitted to cluster analysis.

Results: Four clusters were identified: demoralization and comorbid depression; demoralization and comorbid somatoform/adjustment disorders; demoralization and comorbid anxiety; demoralization without any comorbid DSM disorder. The first cluster included 27.6% of the total sample and was characterized by the presence of DSM-IV mood disorders (mainly major depressive disorder). The second cluster had 18.2% of the cases and contained both DSM-IV somatoform (particularly, undifferentiated somatoform disorder and hypochondriasis) and adjustment disorders. In the third cluster (24.7%), DSM-IV anxiety disorders in comorbidity with demoralization were predominant (particularly, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder). The fourth cluster had 29.5% of the patients and was characterized by the absence of any DSM-IV comorbid disorder.

Conclusions: The findings indicate the need of expanding clinical assessment in the medically ill to include the various manifestations of demoralization as encompassed by the DCPR. Subtyping demoralization may yield improved targets for psychosomatic research and treatment trials.

Key words: Demoralization; DCPR; DSM-IV; Cluster analysis.

Introduction

Several studies confirmed a high prevalence of demoralization among patients with medical disorders, especially with life-threatening or disabling disorders1-7. Demoralization was also found to precede the onset of serious diseases, such as cancer, ischemic heart disease and stroke1,6,8. Despite its clinical and prognostic relevance, demoralization has not been adequately recognized by traditional psychiatric classifications and very few dimensional instruments have been specifically developed for its assessment9. A substantial problem of research in demoralization lies in the various way in which it is defined10 ranging from a non-specific psychological distress11 and a normal response to adversity3 to a specific syndrome resulting from the convergence of distress and subjective incompetence12 that may negatively affect the course of both psychiatric and medical disorders13,14.

Schmale and Engel15 described the pattern of psychological features of the "giving up-given up complex", whose characteristics may be related to the concept of subjective incompetence: feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, perception of diminished competence and loss of mastery and control15. The giving up-given up complex was found to frequently occur in the life setting immediately preceding the onset of disease and can also be exacerbated by the course of illness16. Frank17 suggested that demoralization results from the awareness of being unable to cope with a pressing problem or of having failed to meet one's own or others' expectations and is the main reason why individuals seek psychotherapeutic treatment. All these subclinical aspects, which cannot be identified by psychiatric categories3, are included in the concept of demoralization according to the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR)18,19 (Table 1). DCPR were developed about 15 years ago by an international group of investigators18 with the aim to translate psychosocial variables, issued from a wide body of psychosomatic literature, of prognostic and therapeutic value in the course of physical conditions, into working categories whereby individual patients could be identified. The application of the DCPR operational criteria has permitted to document the occurrence of demoralization across different medical settings, substantiating previous findings that used dimensional tools20,21. In studies utilizing the DCPR, demoralization was found in 14-44% of patients with cardiac22, oncological23, dermatological24, gastrointestinal25 and endocrine conditions26-28, in those recruited in primary care29 and in consultation-liaison psychiatry settings30,31. DCPR demoralization appeared to be far less frequent in the general population32.

The aim of this investigation was to use both DSM and DCPR comorbidity in order to examine the feasibility of subtyping in a highly heterogenous group of medical patients diagnosed as suffering from DCPR demoralization, by a cluster analysis technique.

Methods

Design, procedures and subjects

Patients were recruited from different medical settings in an ongoing multicenter project concerned with the psychosocial dimensions of medical patients33. Even though studies involved in the research project had different aims and sample sizes, they shared a common methodology in the assessment of psychopathology and psychosocial syndromes. Patients were recruited consecutively, with the intent of being representative of their respective patient populations:

1. Consecutive outpatients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (N = 190, 12.2% of the total sample) from the Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Outpatient Clinic of the Scientific Institute of Gastroenterology at Castellana Grotte, Italy.

2. Consecutive outpatients with heart diseases (N = 351, 22.5%) from 3 different sources: 1) 198 patients who underwent heart transplantation from the Heart Transplantation Unit of the Institute of Cardiology at S. Orsola Hospital of Bologna, Italy; 2) 61 consecutive patients with a recent (within 1 month) first myocardial infarction diagnosis from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Program of the Bellaria Hospital in Bologna, Italy; and 3) 92 consecutive patients with a recent (within 1 month) first myocardial infarction diagnosis, from the Institute of Cardiology of University Hospital in Modena, Italy.

3. Consecutive outpatients with endocrine disorders (N = 162, 10.4%) from the Division of Endocrinology of the University of Padova Medical Center, Padova, Italy.

4. Consecutive outpatients who had received a diagnosis of cancer within the past 18 months (N = 104, 6.7%) from the S. Anna University Hospital in Ferrara, Italy.

5. Consecutive outpatients with skin disorders (N = 545, 34.9%) from the Dermopathic Institute of the Immaculate (IDI-IRCCS), Rome, Italy.

6. Consecutive inpatients referred for psychiatric consultation in 2 large university-based general hospitals (N = 208, 13.3%) from the University of Perugia and University of Foggia, Italy.

The study was approved by institutional review boards and local ethics committees, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The patients who were approached were 1700; 140 (8.2%) declined to participate. The most common reason for refusal was lack of time. The total sample included 1560 patients (712 men, 45.6%, and 848 women, 54.4%), with a mean age of 45 (SD = 15.02) years, and a mean of 10.6 (SD = 3.85) years of education. There were no significant differences in terms of sociodemographic variables between the patients who accepted and those who refused.

Assessment

All patients underwent two detailed semi-structured interviews by clinical psychologists or psychiatrists with extensive experience, including psychosomatic research. Psychiatric disorders were investigated with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)34. Diagnoses were grouped according to diagnostic categories such as mood disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, adjustment disorders, and other disorders (including psychotic disorders, eating disorders, sexual dysfunctions and substance use related disorders). Psychosomatic syndromes were diagnosed with the Structured Interview for DCPR35. The DCPR encompass various diagnostic rubrics: abnormal illness behavior (disease phobia, thanatophobia, health anxiety, illness denial), somatization syndromes (persistent somatization, functional somatic symptoms secondary to a psychiatric disorder, conversion symptoms, anniversary reactions), irritability (irritable mood, type A behavior), demoralization, and alexithymia. The interview for DCPR consists of 58 items scored in a yes/no response format evaluating the presence of 1 or more of 12 psychosomatic syndromes. The interview has shown excellent inter-rater reliability, construct validity, and predictive validity for psychosocial functioning and treatment outcome30.

Data analysis

Data were entered in SPSS (SPSS Inc., USA), after which descriptive statistics were calculated. Two-step cluster analysis was performed to organize observations into two or more mutually exclusive groups, where members of the groups shared properties in common36. The following variables were included in the analysis: DSM mood disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, adjustment disorders, other disorders (psychotic disorders, eating disorders, sexual dysfunctions and substance use disorders), absence of any DSM disorder absence of any DSM disorder, DCPR abnormal illness behavior, somatization, irritability and alexithymia.

The two-step cluster method is a scalable cluster analysis algorithm designed to handle large data sets. It can handle both continuous and categorical variables. The two steps are: 1) pre-cluster the cases into many small sub-clusters; 2) cluster the sub-clusters resulting from pre-cluster step into the desired number of clusters. The log-likelihood distance measure was used, with subjects assigned to the cluster leading to the largest likelihood. No prescribed number of clusters was suggested. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used to judge the adequacy of the final solution. Differences in sample characteristics were compared according to cluster membership using independent sample t-tests and chi squared tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. For all tests performed, the significance level was set at 0.05, two-tailed.

Results

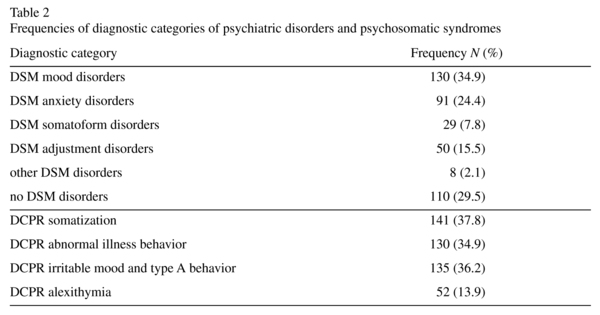

A total of 373 patients (23.9%; 60.3% female) received a diagnosis of demoralization according to DCPR criteria, with a mean age of 48 (SD = 14.57) years, and a mean of 10 (SD = 3.90) years of education. Of these, 263 (70.5%) had at least 1 comorbid Axis I disorder (mainly mood and anxiety disorders), and 308 (82.6%) presented at least 1 comorbid DCPR syndrome. Frequencies for each of the diagnostic categories of psychiatric disorders and psychosomatic syndromes are shown in Table 2.

Two-step cluster analysis yielded 4 clusters, with no exclusion of cases. The composition of the clusters (Figure 1) and the importance of variables within a cluster were then examined.

Figure 1. Distribution of diagnostic categories within each cluster.

The first cluster had 27.6% (N = 103) of the total sample and was characterized by the presence of DSM-IV mood disorders (mainly major depressive disorder); this cluster was named demoralization and comorbid depression.

The second cluster had 18.2% of the cases (N = 68) and contained both DSM-IV somatoform (particularly, undifferentiated somatoform disorder and hypochondriasis) and adjustment disorders; this cluster was named demoralization and comorbid somatoform/ adjustment disorders.

In the third cluster (N = 92; 24.7%), DSM-IV anxiety disorders were predominant (particularly, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder and obsessive- compulsive disorder); this cluster was thus named demoralization and comorbid anxiety.

The fourth cluster had 29.5% (N = 110) of the patients and was characterized by the absence of any DSM-IV comorbid disorder; this cluster was named demoralization without any comorbid DSM disorder.

The frequency and the importance of the remaining variables (e.g., other disorders listed in DSM, DCPR somatization, abnormal illness behavior, irritability, alexithymia) were comparable among the groups, indicating that these diagnostic categories did not make a substantial contribution to cluster formation.

When differences among the cluster groups were examined, no significant differences were found with regard to both gender and years of education. Age differed among the clusters (F3,246 = 4.186; p < 0.01), with patients in the fourth cluster being the oldest (mean age 52 years; SD = 1.76), and those in the second cluster the youngest (mean 43.2 years; SD = 1.88).

With regard to specific medical settings, there were significant differences among the clusters (χ218 = 121.710; p < 0.001): a greater proportion of patients from the Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Outpatient Clinic were found in the first two clusters (N = 14; 32.6% and N = 16; 37.2%, respectively); patients who had received a diagnosis of cancer within the past 18 months were mainly represented in the second cluster (N = 19; 55.9%); a number of patients with skin diseases were contained in both the first and the fourth clusters (N = 22; 29.3% and N = 24; 32%, respectively). The vast majority of inpatients from psychiatric consultation services were present in the first three clusters (N = 19; 35.2%, N = 16; 29.6% and N = 16; 29.6%, respectively). Patients with endocrine disorders were mainly represented in the third cluster (N = 22; 40.7%), as well as those who underwent heart transplantation (N = 27; 42.9%), even though the latter were also present in the fourth cluster (N = 25; 39.7%). About half of patients with a recent first myocardial infarction diagnosis (N = 24; 48%) were found in the fourth cluster.

Discussion

This study has found that almost 24% of patients with various medical illnesses received a diagnosis of demoralization according to DCPR criteria. These results confirm that demoralization is frequent across different medical settings.

The first cluster (demoralization and comorbid depression) encompassed about 30% of cases. This is not a new finding. In fact, previous studies suggested that demoralization can be found in major depression: Klein37 claimed that demoralization may develop in "endogenomorphic depression", and Galeazzi et al.30 and Mangelli et al.10 observed demoralization in more than 50% of medically ill patients with major depression. In a study conducted by Marchesi and Maggini38, the presence of major depression was related to an increase of demoralization scores. Even though demoralization and depression are distinct clinical phenomena10,39-41 in many cases they coexist42. A patient's diminished frustration tolerance and increased mood reactivity while in the hospital are likely due to a sense of demoralization caused by circumstances beyond his control in the hospital. However, his or her more chronic symptoms of anhedonia, social isolation, and poor concentration are suggestive of a coexisting depressive disorder7. There is growing opinion that, within clinical depression, traditional diagnostic systems do not allow differentiation between different mood states commonly experienced in medically ill patients43,44. Clarke and collegues21,45,46 found evidence for different dimensions or types of depression, primarily distinguished by levels of demoralization (hopelessness, helplessness) and anhedonia (diminished interest and ability to experience pleasure). Anhedonia is evident in a number of clusters but did not correlate strongly with the demoralization score.

If on one hand severe and debilitating medical illness can frequently lead to demoralization, on the other hand chronic and disabling mental illness can also be associated with demoralization7. In major depression, demoralization can be viewed as a step in a sequence, starting with the loss of interest and pleasure, the psychopathological core alteration of this disorder37,47. If the loss of pleasure and interest becomes very severe and pervasive, demoralization can follow37. Therefore, demoralization in major depressive patients may represent a psychological response to a prolonged and severe loss of interest and pleasure48. However, in other medically ill patients the relationship between major depression and demoralization might be characterized by a different sequence. In fact, a chronic, severe, incapacitating medical illness may induce feelings of poor self-esteem, helplessness, hopelessness and subjective incompetence5,21,30,49,50. It cannot be excluded that demoralization, once occurred, may predispose medically ill patients to suffer from major depression, which in turn worsen the feelings of poor self-esteem, helplessness and hopelessness. Moreover, it could be that demoralization, when associated with clinical depression, individuates a subgroup of patients at a greater risk of a worse outcome8. This could happen since the addition of demoralization to major depressive disorder results in decreased psychological well-being dimensions, such as autonomy, positive relations and self-acceptance as recently found in a population of heart transplanted patients51.

The second cluster encompassed 18.2% of the cases and was characterized by both DSM-IV somatoform (particularly, undifferentiated somatoform disorder and hypochondriasis) and adjustment disorders. Both diagnostic rubrics have recently undergone considerable criticism as to their clinical usefulness52,53. Clarke et al.21 found that in 312 patients admitted to hospital with a range of medical conditions (cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, respiratory, rheumatological and neurological), clusters of high self-reported distress (demoralization and demoralized grief) were significantly associated with DSM-IV somatoform disorders. Patients with somatization syndromes might present a bias to interpret minor physical changes as a possible sign of a severe illness. Affective consequences such as demoralization might present a negative feed-back loop that helps to maintain the problem54. On the other hand, adjustment disorders have been found to be the most frequent psychiatric diagnosis in the medically ill. Problems have been raised, however, as to their clinical value. In the study by Grassi et al.43 one hundred patients with medical illness and a diagnosis of DSM-IV adjustment disorder were interviewed according to the DCPR system. A considerable overlap was shown between adjustment disorders and DCPR clusters related to somatization (37%) and demoralization (33%), confirming our findings. While researchers have highlighted the need to include demoralization in the psychiatric nomenclature55, currently it is often referred to as adjustment disorder. However, it has been argued that adjustment disorder does not place sufficient emphasis on the personal narrative of incompetence that characterizes the lives of demoralized individuals4.

In the third cluster (24.7%), DSM-IV anxiety disorders (particularly, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder) in comorbidity with demoralization were predominant. Since anxiety disorders can be severely disabling and impairing56, it is not surprising that a number of patients experience demoralization57. The phenomenon of demoralization has been largely applied to clinical populations to explain a developmental spectrum of psychopathology. Frank17 observed both anxiety and depressive symptomatology as direct expressions of demoralization. Research indicates that if an individual endures internal or external stressors that are perceived as severe, then anxiety levels increase5. When anxiety levels increase, an individual may feel the situation is uncontrollable, leading to helplessness. If the feeling of helplessness is not attended to, then hopelessness and the inability to cope will develop5. Anxiety then might evolve into subsequent depression by a sort of process of demoralization58. The relation between symptoms of anxiety/depression and demoralization, as suggested by Grassi et al.43, reopens the question whether demoralization is part of the anxious-depressive spectrum.

The fourth cluster had 29.5% of the patients and was characterized by the absence of any DSM-IV comorbid disorder. This finding is clinically relevant. Through the use of the DCPR among medically ill patients, it has been confirmed that demoralization is a construct that is not necessarily related to psychiatric disorders. In a large study of 809 medical patients, the frequency of DCPR demoralization was 30%, whereas the frequency of DSM-IV major depression was only 17%. Of interest, 44% of patients with major depression did not meet the DCPR criteria for demoralization, whereas up to 69% of those with demoralization did not meet the criteria for major depression10. Patient's inability to cope with some pressing problems, feelings of helplessness, or hopelessness, or giving up could represent key factors for the development of illnesses or contributing factor to the expression of physical or mental disease activity. Demoralization should thus be examined carefully, avoiding the common tendency to dismiss it as an understandable (and thus not requiring attention or treatment) condition in patients with medical illnesses10. Preliminary clinical findings suggest that a careful diagnosis of demoralization may lead to effective treatment of both psychological and somatic symptoms5,59. There remains the need to further investigate if treating sub-clinical syndromes can improve quality of life and reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality in these patients60.

The study has limitations due to its cross-sectional nature. We do not know, in fact, the longitudinal course of these clusters. However, the findings of this study highlight the importance of detecting demoralization alone or in comorbidity with major depression, somatization, adjustment and anxiety disorders. Exclusive reliance on psychiatric diagnostic criteria has impoverished the clinical process and does not reflect the complex thinking that underlies decisions in psychiatric practice61. Identifying and subtyping demoralization in the setting of medical disease may yield improved targets for research and treatment trials, as is currently advocated in major depression62-64.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Antonello Bellomo, MD, Silvia Ferrari, MD, Luigi Grassi, MD, Angelo Picardi, MD, Roberto Quartesan, MD, Marco Rigatelli, MD, and Nicoletta Sonino, MD, for the use of collaborative data.

References

1. Grossarth-Maticek R, Bastiaans J, Kanazir DT. Psychosocial factors as strong predictors of mortality from cancer, ischaemic heart disease and stroke: the Yugoslav prospective study. J Psychosom Res 1985; 29(2): 167-176. [ Links ]

2. Anda R, Williamson D, Jones D, Macera C, Eaker E, Glassman A, et al. Depressed affect, hopelessness, and the risk of ischemic heart disease in a cohort of U.S. adults. Epidemiology 1993; 4(4): 285-294. [ Links ]

3. Slavney PR. Diagnosing demoralization in consultation psychiatry. Psychosomatics 1999; 40(4): 325-329. [ Links ]

4. Angelino AF, Treisman GJ. Major depression and demoralization in cancer patients: diagnostic and treatment considerations. Support Care Cancer 2001; 9(5): 344-349. [ Links ]

5. Clarke DM, Kissane DW. Demoralization: its phenomenology and importance. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2002; 36(6): 733-742. [ Links ]

6. Schuitemaker GE, Dinant GJ, van der Pol GA, Appels A. Assessment of vital exhaustion and identification of subjects at increased risk of myocardial infarction in general practice. Psychosomatics 2004; 45(5): 414-418. [ Links ]

7. Jacobsen JC, Maytal G, Stern TA. Demoralization in medical practice. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007; 9(2): 139-143. [ Links ]

8. Rafanelli C, Roncuzzi R, Milaneschi Y, Tomba E, Colistro MC, Pancaldi LG, et al. Stressful life events, depression and demoralization as risk factors for acute coronary heart disease. Psychother Psychosom 2005; 74(3): 179-184. [ Links ]

9. Fabbri S, Fava GA, Sirri L, Wise T. Development of a new assessment strategy in psychosomatic medicine: The Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research. In: Porcelli P, Sonino N, editors. Psychological factors affecting medical conditions. A new classification for DSM-V. Basel, CH: Karger; 2007. p. 1-20. [ Links ]

10. Mangelli L, Fava GA, Grandi S, Grassi L, Ottolini F, Porcelli P, et al. Assessing demoralization and depression in the setting of medical disease. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(3): 391-394. [ Links ]

11. Dohrenwend BP, Shrout PE, Egri G, Mendelsohn FS. Nonspecific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37(11): 1229-1236. [ Links ]

12. de Figueiredo JM. Depression and demoralization: phenomenologic differences and research perspectives. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34(5): 308-311. [ Links ]

13. Myers JK, Lindenthal JJ, Peper MP. Life events, social integration and psychiatric symptomatology. J Helth Soc Behav 1975; 16(4): 421-427. [ Links ]

14. Craig TJ, Brown GW. Goal frustration and life events in the etiology of painful gastrointestinal disorder. J Psychosom Res 1984; 28(5): 411-421. [ Links ]

15. Schmale AH, Engel GL. The giving up-given up complex illustrated on film. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1967; 17(2): 133-145. [ Links ]

16. Schmale AH. Giving up as a final common pathway to changes in health. Adv Psychosom Med 1972; 8: 20-40. [ Links ]

17. Frank JD. Psychotherapy: the restoration of morale. Am J Psychiatry 1974; 131: 271-274. [ Links ]

18. Fava GA, Freyberger HJ, Bech P, Christodoulou G, Sensky T, Theorell T, et al. Appendix 1. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychosomatic research. In: Porcelli P, Sonino N, editors. Psychological factors affecting medical condition. A new clasiffication for DSM-V. Basel, CH: Karger; 207. p. 169-173. [ Links ]

19. Rafanelli C, Roncuzzi R, Finos L, Tossani E, Tomba E, Mangelli L, et al. Psychosocial assessment in cardiac rehabilitation. Psychother Psychosom 2003; 72(6): 343-349. [ Links ]

20. Feldman D, Rabinowitz J, Yehuda YB. Detecting psychological distress among patients attending secondary health care clinics: Self-report and physician rating. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1995; 17(6): 425-432. [ Links ]

21. Clarke DM, Smith GC, Doweb DL, McKenzieac DP. An empirically derived taxonomy of common distress syndromes in the medically ill. J Psychosom Res 2003; 54(4): 323-330. [ Links ]

22. Ottolini F, Modena MG, Rigatelli M. Prodromal symptoms in myocardial infarction. Psychother Psychosom 2005; 74(5): 323-327. [ Links ]

23. Grassi L, Sabato S, Rossi E, Biancosino B, Marmai L. Use of the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research in oncology. Psychother Psychosom 2005; 74(2): 100-107. [ Links ]

24. Picardi A, Porcelli P, Pasquini P, Fassone G, Mazzotti E, Lega I, et al. Integration of multiple criteria for psychosomatic assessment of dermatological patients. Psychosomatics 2006; 47(2): 122-128. [ Links ]

25. Porcelli P, de Carne M, Fava GA. Assessing somatization in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Integration of different criteria. Psychother Psychosom 2000; 69(4): 198-204. [ Links ]

26. Sonino N, Navarrini C, Ruini C, Ottolini F, Paoletta A, Fallo F, et al. Persistent psychological distress in patients treated for endocrine disease. Psychother Psychosom 2004; 73(2): 78-83. [ Links ]

27. Sonino N, Ruini C, Navarrini C, Ottolini F, Sirri L, Paoletta A, et al. Psychosocial impairment in patients treated for pituitary disease. A controlled study. Clin Endocrinol 2007; 67(5): 719-726. [ Links ]

28. Sonino N, Peruzzi P. A psychoneuroendocrinology service. Psychother Psychosom 2009; 78(6): 346-351. [ Links ]

29. Ferrari S, Galeazzi GM, Mackinnon A, Rigatelli M. Frequent attenders in primary care: impact of medical, psychiatric and psychosomatic diagnoses. Psychother Psychosom 2008; 77(5): 306-314. [ Links ]

30. Galeazzi GM, Ferrari S, Mackinnon A, Rigatelli M. Interrater reliability, prevalence and relation to ICD-10 diagnoses of the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research in consultation-liaison psychiatry patients. Psychosomatics 2004; 45(5): 386-393. [ Links ]

31. Porcelli P, Bellomo A, Quartesan R, Altamura M, Iuso S, Ciannameo I, et al. Psychosocial functioning in consultation-liaison psychiatry patients: influence of psychosomatic syndromes, psychopathology and somatization. Psychother Psychosom 2009; 78(6): 352-358. [ Links ]

32. Mangelli L, Semprini F, Sirri L, Fava GA, Sonino N. Use of the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR) in a community sample. Psychosomatics 2006; 47(2): 143-146. [ Links ]

33. Porcelli P, Sonino N. Preface. In: Porcelli P, Sonino N, editors. Psychological factors affecting medical condition. A new classification for DSM-V. Basel, CH: Karger; 2007. p. VII-X. [ Links ]

34. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. SCID-I - Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (Italian version by Mazzi F, Morosini P, de Girolamo G, Lussetti M, Guaraldi GP). Firenze, IT: Organizzazioni Speciali; 2000. [ Links ]

35. Mangelli L, Rafanelli C, Porcelli P, Fava GA. Appendix 2. Interview for the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research. In: Porcelli P, Sonino N, editors. Psychological factors affecting medical conditions. A new classification for DSM-V. Basel, CH: Karger; 2007. p. 174-181. [ Links ]

36. Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ. Finding groups in data: an introduction to cluster analysis. New York, NY: Wiley; 1990. [ Links ]

37. Klein DF. Endogenomorphic depression: A conceptual and terminological revision. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31(4): 447-454. [ Links ]

38. Marchesi C, Maggini C. Socio-demographic and clinical features associated with demoralization in medically ill in-patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007; 42(10): 824-829. [ Links ]

39. Jacobsen JC, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, Friedlander RJ, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG. Depression and demoralization as distinct syndromes: Preliminary data from a cohort of advanced cancer patients. IJPC 2006; 12(1): 8-15. [ Links ]

40. Strada EA. Grief, demoralization, and depression: Diagnostic challenges and treatment modalities. Primary Psychiatry 2009; 16(5): 49-55. [ Links ]

41. Wellen M. Differentiation between demoralization, grief, and anhedonic depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2010; 12: 229-233. [ Links ]

42. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Demoralization in patients with medical illness. Psychiatry 2010; 7(8): 42-45. [ Links ]

43. Grassi L, Mangelli L, Fava GA, Grandi S, Ottolini F, Porcelli P, et al. Psychosomatic characterization of adjustment disorders in the medical setting: Some suggestions for DSM-V. J Affect Dis 2007; 101(1): 251-254. [ Links ]

44. Guidi J, Fava GA, Bech P, Paykel E. The Clinical Interview for Depression: A comprehensive review of studies and clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom 2011; 80(1): 10-27. [ Links ]

45. Clarke DM, Mackinnon AJ, Smith GC, McKenzie DP, Herrman HE. Dimensions of psychopathology in the medically ill. A latent trait analysis. Psychosomatics 2000; 41: 418-425. [ Links ]

46. Clarke DM, Kissane DW, Trauer T, Smith GC. Demoralization, anhedonia and grief in patients with severe physical illness. World Psychiatry 2005; 4(2): 96-105. [ Links ]

47. Pichot P. Classification of depressive states. Psychopathology 1986; 19(2): 12-16. [ Links ]

48. Chouinard G, Chouinard VA, Corruble E. Beyond DSM-IV bereavement exclusion criterion E for major depressive disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2011; 80(1) :4-9. [ Links ]

49. Grassi L, Rossi E, Sabato S, Cruciani G, Zambelli M. Diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research and psychosocial variables in breast cancer patients. Psychosomatics 2004; 45(6): 483-491. [ Links ]

50. Vehling S, Lehmann C, Oechsle K, Bokemeyer C, Krüll A, Koch U, et al. Is advanced cancer associated with demoralization and lower global meaning? The role of tumor stage and physical problems in explaining existential distress in cancer patients. Psychooncology 2012: 21(1): 54-63. [ Links ]

51. Grandi S, Sirri L, Tossani E, Fava GA. Psychological characterization of demoralization in the setting of heart transplantation. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72(5): 648-654. [ Links ]

52. Wise TN. Diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research are necessary for DSM V. Psychother Psychosom 2009; 78(6): 330-332. [ Links ]

53. Semprini F, Fava GA, Sonino N. The spectrum of adjustment disorders: too broad to be clinically helpful. CNS Spectr 2010; 15(6): 382-388. [ Links ]

54. Rief W, Exner C. Psychobiology of somatoform disorders. In: D'haenen HAH, den Boer JA, Willner P, editors. Biological psychiatry. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley; 2002. p. 1063-1077. [ Links ]

55. Lloyd-Williams M, Reeve J, Kissane D. Distress in palliative care patients: developing patient-centred approaches to clinical management. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44(8): 1133-1138. [ Links ]

56. Beutel ME, Bleichner F, von Heymann F, Tritt K, Hardt J. Anxiety disorders and comorbidity in psychosomatic inpatients. Psychother Psychosom 2010; 79(1): 58. [ Links ]

57. Goodwin R, Olfson M, Feder A, Fuentes M, Pilowsky DJ, Weissman MM. Panic and suicidal ideation in primary care. Depress Anxiety 2001; 14: 244-246. [ Links ]

58. Schindel-Allon I, Aderka IM, Shahar G, Stein M, Gilboa-Schechtman E. Longitudinal associations between post-traumatic distress and depressive symptoms following a traumatic event: a test of three models. Psychol Med 2010; 40(10): 1669-1978. [ Links ]

59. Porcelli P, De Carne M. Non-fearful panic disorder in gastroenterology. Psychosomatics 2008; 49: 543-545. [ Links ]

60. Rafanelli C, Roncuzzi R, Ottolini F, Rigatelli M. Psychological factors affecting cardiologic conditions. In: Porcelli P, Sonino N, editors. Psychological factors affecting medical condition. A new classification for DSM-V. Basel, CH: Karger; 2007. p. 72-108. [ Links ]

61. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Tomba E. The clinical process in psychiatry. A clinimetric approach. J Clin Psychiatry 2012; 73(2): 177-184. [ Links ]

62. Baumeister H, Parker G. A second thought on subtyping major depression. Psychother Psychosom 2010; 79(6): 388-389. [ Links ]

63. Bech P. Struggle for subtypes in primary and secondary depression and their mode-specific treatment or healing. Psychother Psychosom 2010; 79(6): 331-338. [ Links ]

64. Lichtenberg P, Belmaker RH. Subtyping major depressive disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2010; 79(3) :131-135. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Chiara Rafanelli, M.D., Ph.D

Department of Psychology, University of Bologna

Viale Berti Pichat 5

40127 Bologna, Italy

Phone: +39-051-2091847

E-mail: chiara.rafanelli@unibo.it

Received: 3 September 2012

Revised: 1 December 2012

Accepted: 19 December 2012