Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.28 no.4 Zaragoza oct./dic. 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632014000400003

A prospective study of natural recovery from cannabis use in early psychosis

Shane Rebgetz*,**; Leanne Hides*; David J. Kavanagh*; Sharon Dawe***; Ross M. Young*

* Institute of Health & Biomedical Innovation and School of Psychology & Counselling, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland. Australia

** Queensland Health, Metro-North Health Service District, Redcliffe-Caboolture Mental Health Service, Queensland. Australia

*** School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland. Australia

The collection of the data was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council. Leanne Hides is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: Cannabis use is common in early psychosis and has been linked to adverse outcomes. However, factors that influence and maintain change in cannabis use in this population are poorly understood. An existing prospective dataset was used to predict abstinence from cannabis use over the 6 months following inpatient admission for early psychosis.

Methods: Participants were 67 inpatients with early psychosis who had used cannabis in the 6 weeks prior to admission. Current diagnoses of psychotic and substance use disorders were confirmed using a clinical checklist and structured diagnostic interview. Measures of clinical, substance use and social and occupational functioning were administered at baseline and at least fortnightly over the 6-month follow up.

Results: No substance use or clinical variables were associated with 6-months’ of cannabis abstinence. Only Caucasian ethnicity, living in private accommodation and receiving an income before the admission were predictive. Only private accommodation and receiving an income were significant predictors of abstinence when these variables were entered into a multivariate analysis.

Conclusions: While the observed relationships do not necessarily imply causation, they suggest that more optimal substance use outcomes could be achieved by addressing the accommodation and employment needs of patients.

Key words: Psychosis; Substance use; Recovery.

Introduction

Both a heightened risk of cannabis use in psychosis and the adverse biological, psychological, and social consequences of cannabis use in psychosis are well established1,2,3. However, clinical trials examining the impact of substance use interventions for people with psychosis have given inconsistent and disappointing results4,5,6. Several studies have found that substance users with psychosis who undergo assessment only or minimal treatment achieve similar reductions in substance use over time, to those receiving more intensive substance use treatments7,8,9. A greater understanding of natural recovery from substance use in people with psychosis may offer new insights into more effective strategies for addressing it in this population.

Previous research has suggested that continued substance use in people with early psychosis is associated a number of variables, such as younger age, male gender, unemployment, non-completion of secondary school, single marital status and greater cannabis use at baseline10,11. Unsurprisingly, more severe substance use at baseline (e.g. severe substance dependence) also predicts later substance use among people with more chronic psychotic disorders12. It therefore may be expected that reduction in these risk factors may be associated with a lower rate of substance use in early psychosis. To our knowledge no studies have examined which factors predict abstinence of cannabis use in an early psychosis population.

Only a handful of studies have examined predictors of cannabis cessation in people with psychotic disorders13,14. Few findings have been replicated. A recent study conducted by the investigators, found that the presence of a cannabis use disorder only (i.e. without other concurrent substance misuse) and higher levels of premorbid social and occupational functioning were significant predictors of later cessation or reduction of substance use in a treated cohort of first episode patients with psychosis and substance use disorder15. However, no distinction between those who ceased and those who reduced their use was made. The identification of factors that lead to continuous abstinence is of particular interest, as any use is likely to be problematic in this group.

Lifestyle factors that enable maintenance of abstinence include the avoidance of situations in which cannabis was previously used, and the development of interests (e.g., diet, exercise, sport) that are inconsistent with cannabis use16. Such factors have been implicated in sustained abstinence in people with severe mental illness and alcohol dependence17.

In summary, previous research has identified the following predictors of reduction in substance use among people with psychosis: older age, female gender, being employed, less severe cannabis and other substance use, engagement in social activities, better premorbid adjustment and less severe mental health symptoms. This is the first study to identify demographic, substance use, clinical, family and social predictors (assessed at the time of psychiatric admission) of cannabis cessation over the following 6 months in an early psychosis sample.

Methods

Sample and Context

An existing prospective data set collected by Hides et al.18 to examine the influence of cannabis use on psychotic relapse over a 6-month follow-up was used for this study. The original sample consisted of 121 consecutively admitted patients with early psychosis recruited from three public hospitals in Brisbane's Inner, Western and Southern Suburbs between March and October 2000. These participants consented to all assessment periods and ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and the relevant hospital HREC's. Inclusion criteria included meeting DSM-IV criteria for a current Psychotic Disorder or Mood Disorder with Psychotic Features19 and having less than three previous psychotic epi-sodes. A mixed sample of patients (i.e., psychosis and affective psychosis) was selected, as they represent typical clinical presentations to mental health services in early stages of psychosis, when diagnosis is often unclear. Exclusion criteria included diagnoses of Psychotic Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition or Intellectual Disability. Eighty-one (67%) people agreed to participate in the baseline assessment in hospital and a 6-month follow up, comprising monthly face-to-face visits, interspersed with telephone calls, to provide weekly contact for the first 3 months, followed by fortnightly contact for another 3 months (see 18 for further information). The present study focused on a subset of 67 participants (83% of the follow-up sample) who had current cannabis dependence (N = 57) or had used cannabis in the 6 weeks prior to admission (N = 10). Cannabis cessation, the key outcome measure, was defined as abstinence from cannabis use throughout the study period from baseline to a 6-month follow-up.

Baseline Measures

Demographic assessments included age, gender, employment, receiving an income (through employment and government benefits), marital status, parental occupation, current living arrangements, education, ethnicity, diagnosis, age of first diagnosed and admitted, number of episodes and hospital admissions, length of current and previous hospitalisations, current and discharge medication, family history of psychosis and other psychiatric disorders. This information was verified against medical records.

The Operational Criteria Checklist (OP-CRIT; 20) was used to confirm psychotic diagnoses, based on the medical record. The Interview for Retrospective Assessment of Schizophrenia (IRAOS; 21) verified participants' age at onset of psychotic symptoms. The IRAOS is an objective, reliable and valid assessment tool in studying onset, pre-psychotic prodrome and early course of psychosis21. The 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; 22) was administered to assess current psychiatric symptoms and has shown high levels of reliability and validity in dual diagnosis populations23.

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 2.1 (CIDI; 24) Section L identified whether substance abuse or dependence was present in the 12 months prior to admission. A Timeline Followback (TLFB; 25) measured the frequency (days) and quantity of cannabis and other substance use in the 6 weeks prior to admission by anchoring substance use against key life events to assist recall25,26. TLFBs have well-established reliability and validity25,26. Cannabis effect expectancies were identified using the 23-item Cannabis Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ; 27). Positive and negative expec-tancies on the CEQ have demonstrated concurrent validity with cannabi use and dependence in a treatment sample of cannabis users In a treatment sample of cannabis users, higher positive cannabis expectancy scores were associated with greater cannabis use, while higher negative expectancy scores predicted greater cannabis dependence28.

Key life events were defined according to the Psychiatric Epidemiological Interview - Life Events Scale (PERI-LES: 29) measured on the TLFB. The Family Environment Scale (FES; 30) was used to measure family relationships (conflict, expressiveness, cohesion) in current family functioning for those participants' in regular contact with their families. The FES has demonstrated discriminative and predictive validity in psychotic populations31. The Quality of Life (QOL-Brief Version; 32) scale measured objective quality of life and global wellbeing in the previous 12 months. The scale has shown good levels of inter-rater reliability and validity in people with schizophrenia33. The Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS; 34) assessed premorbid functioning in the 6 months preceding first admission. It has demonstrated good levels of inter-rater reliability and validity amongst people with schizophrenia34.

Monitoring Measures

Psychiatric symptoms were monitored using the BPRS22 throughout the 6-month follow-up. Only BPRS items that did not require interviewer observation could be included in telephone interviews. BPRS positive, negative and depression-anxiety symptom scores were derived35. TLFBs measured the frequency (days) and quantity of cannabis and other substance use, life events, life stress (subjectively rated from 0 to 10) and medication adherence (in days) at least fortnightly over the 6-month follow-up.

Participants underwent urine drug screening at 6 months or while in hospital, to verify self-reports of recent substance use and antipsychotic medication adherence. Urine was screened using a cannabis immunoassay and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. There was a high level of agreement between these assays and self-reported CU (Cohen's kappa = 0.90).

Statistical analysis

Candidate predictors of cannabis cessation identified in the literature to date (listed in Table 2) were initially entered into a series of univariate logistic regressions to identify predictors of cannabis cessation. Other plausible predictors that were also examined included living arrangements (living in private accommodation), ethnicity (being Cauca-sian), financial status (having an income), total cannabis expectancy score, age of onset of cannabis use, family relationships (conflict, expressiveness, cohesion) and family history of psychosis or other mental illness. Significant predictors (p < 0.05) were entered simultaneously into a multivariate logistic regression, to identify which variables retained significance (p < 0.05) when other predictors were controlled for. Analyses were performed using IBM® SPPS® Version 22.0.

Results

Participant characteristics

The sample had a mean age of 24.5 (SD 5.2) years, and the majority were male (N = 52/67; 78%), with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder (N = 48/67; 72%). The demographic, substance use and clinical characteristics of the patients who did and not cease cannabis use from baseline to the 6-month follow up assessment are displayed in Table 1. While data were not available on whether they received brief advice concerning their substance use, none received extensive inpatient or outpatient specialist treatment for addiction, and 66% (N = 44) did not see a psychiatrist or case manager during the follow-up period.

Despite the absence of specific substance use treatment, 19 participants (28%) did not use cannabis at all over the 6-month follow-up. In fact, 27% (18/67) refrained from any illicit substance use during the follow up period. Almost 80% (N = 53/67; 79%) abstained from methamphetamine use over the 6-months, but only 10/67 (15%) abstained from alcohol.

Univariate predictors of cessation in cannabis use

Separate univariate logistic regressions identified four predictors of cannabis cessation (see Table 2). Only living in private accommodation, receiving an income at baseline and Caucasian ethnicity predicted cessation with p < 0.05 on the Wald Test. Notably, neither baseline symptoms (on the BPRS) nor any baseline substance use measure (including baseline measures of quantity/frequency of cannabis, other illicit drug or alcohol use, the severity of cannabis dependence or cannabis expectancies on the CEQ) predicted subsequent cannabis cessation.

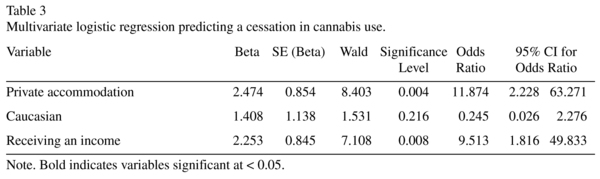

Multivariate predictors of cessation in cannabis use

A multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify which of these univariate predictors retained significance when entered simultaneously into the analysis (see Table 3). The full model significantly distinguished between participants who had ceased and continued cannabis use post-admission (χ2 (3, N = 67) = 21.26, p < 0.001). The model explained 27% (Cox and Snell R square) to 39% (Nagelkerke R squared) of the variance, and correctly classified 81% of cases. As shown in Table 3, only private accommodation and receiving an income made a significant unique contribution. The strongest predictor of cannabis cessation was private accommodation, recording an odds ratio of 11.87, while receiving an income increased the odds by 9.51.

Little change in the model was found if participants with only cannabis dependence (N = 57; i.e. excluding abuse) were included, χ2 (3, N = 57) = 17.83, p < 0.001. The equation explained between 27% (Cox and Snell R2) and 38% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance, and correctly classified 79% of cases. The same unique predictors emerged.

Discussion

This was the first prospective naturalistic study to examine predictors of cannabis cessation, in an early psychosis sample. Almost 30% of cannabis using early psychosis patients ceased cannabis use for at least 6 months following an inpatient admission for acute psychosis. A similar proportion refrained from any illicit substance use at all during the follow up. These results are consistent with a growing body of work indicating that recovery from substance use can occur in early psychosis in the absence of significant substance use treatment36,37,38,39,40.

In order to increase current understanding of natural recovery from cannabis use in early psychosis, the current study examined the impact of a wide range of potential demographic, clinical, substance use, social, treatment, functional and quality of life variables on cannabis cessation. Having private accommodation and an income at admission provided the only significant unique predictions of cannabis cessation in the multivariate analysis. Early psychosis patients living in private accommodation and those with an income were 11 and 9 times more likely to abstain from cannabis use respectively. These findings were consistent with those of Maisto et al.41, who found that living in stable accommodation (group homes), which often restricted access to substances and provided structure, was a factor associated with changing substance use patterns. Individuals who have stronger predictability in their lives may reduce their substance use, due to the associated increases in positive social interactions outside of substance use and decreased stress41. Similarly, having an income may allow people to engage in other activities outside of cannabis use (e.g., sport, hobbies), providing a sense of belonging and acceptance42. These activities may engage people in a positive social network, away from substance-using peers and provide an opportunity for a reappraisal of the value of more functional rewards and of the financial and opportunity costs associated with cannabis use16,42,43.

The protective effects of both private accommodation and an income are open to other interpretations. For example, they may reflect higher levels of cognitive and social functioning, which may then allow greater control over cannabis use. While cognitive functioning was not assessed, it is notable that the presence of social activities and premorbid adjustment were not significant univariate predictors. These characteristics might also be expected among individuals with less severe levels of cannabis use and cannabis-related problems (e.g. less interference with an ability to obtain financial support, a greater proportion of income being available for accommodation). However, the fact that neither the extent of cannabis and other substance use nor the presence of cannabis dependence at baseline predicted later cannabis cessation renders this hypothesis unlikely.

The finding that neither baseline cannabis nor other substance use was associated with cannabis cessation was both noteworthy and surprising. It differs from the observation of Wade et al.11 that continued substance use at 15 months was associated with heavy cannabis use prior to baseline, but was consistent with a chart audit by Dekker et al.44 that found no association.

The presence of polysubstance use is often used as an indicator of severity. While almost 50% of the sample were polysubstance users (defined as cannabis plus other substances) in the 6 weeks prior to admission, there was no significant difference in the proportion of polysubstance users and cannabis users who achieved abstinence from cannabis use or any substance use over the 6-month follow-up. This does not accord with our recent finding that first-episode patients with a cannabis use disorder at baseline were more likely to have reduced or ceased substance use at 18-months follow-up than were those with polysubstance use disorders15. However, that study relied on file audits and included reductions in consumption, whereas the current study focused on complete abstinence, and systematically measured substance use at least fortnightly over 6 months follow-up.

Unlike previous studies conducted by our group45 there was no association between positive and negative cannabis expectancies and cannabis cessation. Notably, however, the current study is the first to examine the association between cannabis expectancies and abstinence.

Contrary to our hypotheses, neither male gender, younger age, incomplete secondary school, nor unemployment46,47 were significant predictors of cannabis cessation. These factors are typically associated with the risk of substance use and related functional impacts rather than with cessation of use among substance users. Equally, the severity of BPRS psychiatric symptoms at baseline was not associated with cannabis cessation.

This study had a relatively small sample size, and while it was adequate -particularly for the univariate predictions48- greater confidence in our conclusions would be given by a replication using a larger sample. Abstinence from cannabis use was assessed over 6 months, whereas some other studies have used a 12-month criterion for abstinence49. On the other hand, the current study had weekly assessments of cannabis use for the first 3 months, followed by fortnightly assessments for 3 months-a level of monitoring that was much more intensive than is typically obtained. The high degree of concordance between self-reported substance use and urine drug screens in the hospital and at 6 months gave further credence to the results.

Finally, while it is plausible that treatment in the post discharge period may influence abstinence, it is noteable that this was a relatively uncommon occurrence. Only a third of participants received specialist psychiatric care during the follow-up, and none received substance use treatment. While some participants may have received brief, opportunistic intervention, the study provides a close approximation of a naturalistic follow-up.

Clinical Implications and Future Research Directions

This was the first prospective study to examine the role of a range of demographic, clinical, substance use, family/social, quality of life and functional variables on cannabis cessation in an early psychosis sample that did not receive substantial substance use treatment. Only private accommodation and access to a regular income predicted cannabis cessation for 6-months following an inpatient admission.

While the current results could be due to an unmeasured factor such as the level of cognitive functioning, the prospective design and the wide range of assessed predictors gave credence to the results. Addressing basic needs is likely to be a vital step in recovery. Our results suggest that optimal substance use outcomes from early psychosis services may be achieved by address the accommodation and employment needs of patients as well as their mental health symptoms. Given the size of the effect found addressing the lack of suitable accommodation via policy and community advocacy is a key priority. Such an approach is consistent with comprehensive case management, and with a strengths-based approach to the challenges of early psychosis.

Acknowledgements

Nil.

Conflict of Interest

The Authors have declared no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Contributors

Rebgetz, Hides, and Kavanagh designed this study. Hides, Dawe, Kavanagh and Young wrote the original protocol and Hides collected the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper and have approved the final manuscript.

References

1. Cleary M, Hunt GE, Matheson S, Walter G. Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance misuse: Systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009; 65 (2): 238-258. [ Links ]

2. Horsfall J, Cleary M, Hunt GE, Walter G. Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illnesses and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): A review of empirical evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009; 17 (1): 24-34. [ Links ]

3. Kavanagh DJ, Mueser KT. Current evidence on integrated treatment for serious mental disorder and substance misuse. J Norwegian Psycholol Ass. 2007; 44 (5): 618-637. [ Links ]

4. Hjorthøj C, Fohlmann A, Nordentoft M. Reprint of "Treatment of cannabis use disorders in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders - a systematic review". Addict Behav. 2009; 34 (10): 846-51. [ Links ]

5. Cleary M, Hunt GE, Matheson S, Siegfried N, Walter G. Psychosocial treatment programs for people with both severe mental illness and substance misuse. Schizophr Bull. 2008; 34 (2): 226-8. [ Links ]

6. Kavanagh DJ, Young R, White A, Saunders JB, Wallis J, Shockley N, et al. A brief motivational intervention for substance misuse in recent-onset psychosis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004; 23 (2): 151-5. [ Links ]

7. Edwards J, Elkins K, Hinton M, Harrigan SM, Donovan K, Athanasopoulos O, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a cannabis-focused intervention for young people with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006; 114 (2): 109-17. [ Links ]

8. Gleeson JF, Cotton SM, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Wade D, Gee D, Crisp K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of relapse prevention therapy for first-episode psychosis patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009; 70 (4): 477-86. [ Links ]

9. Archie S, Rush BR, Akhtar-Danesh N, Norman R, Malla A, Roy P, et al. Substance use and abuse in first-episode psychosis: Prevalence before and after early intervention. Schizophr Bull. 2007; 33 (6): 1354-63. [ Links ]

10. Lambert M, Conus P, Lubman DI, Wade D, Yuen H, Moritz S et al. The impact of substance use disorders on clinical outcome in 643 patients with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005; 112 (2): 141-8. [ Links ]

11. Wade D, Harrigan S, Edwards J, Burgess PM, Whelan G, McGorry PD. Course of substance misuse and daily tobacco use in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2006; 81 (2-3): 145-50. [ Links ]

12. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA. Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1995; 46 (3): 248-51. [ Links ]

13. Rebgetz S, Kavanagh DJ, Hides L. Can exploring natural recovery from substance misuse in psychosis assist with treatment? a review of the current research. Addict Behav Forthcoming. 2014. [ Links ]

14. Childs HE, McCarthy-Jones S, Rowse G, Turpin G. The journey through cannabis use: A qualitative study of the experiences of young adults with psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011; 199 (9): 703-8. [ Links ]

15. Rebgetz S, Conus P, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Cotton S, Schimmelmann BG, et al. Predictors of substance use reduction in an epidemiological first-episode psychosis cohort. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013; DOI: 10.1111/eip.12067. [ Links ]

16. Ellingstad TP, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Eickleberry L, Golden CJ. Self-change: A pathway to cannabis abuse resolution. Addict Behav. 2006; 31 (3): 519-30. [ Links ]

17. Stasiewicz PR, Bradizza CM, Maisto SA. Alcohol problem resolution in the severely mentally ill: A preliminary investigation. J Subst Abuse. 1997; 9: 209-22. [ Links ]

18. Hides L, Dawe S, Kavanagh DJ, Young RM. Psychotic symptom and cannabis relapse in recent-onset psychosis. Prospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 189: 137-43. [ Links ]

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic & statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing. 2000. [ Links ]

20. McGuffin P, Farmer AE, Harvey I. A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness. Development and reliability of the OPCRITsystem. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991; 48 (8): 764-70. [ Links ]

21. Häfner H, Riecher-Rössler A, Hambrecht M, Maurer K, Meissner S, Schmidtke A, et al. IRAOS: An instrument for the assessment of onset and early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1992; 6 (3): 209-23. [ Links ]

22. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962; 10: 799-812. [ Links ]

23. Lykke J, Hesse M, Austin SF, Oestrich I. Validity of the BPRS, the BDI and the BAI in dual diagnosis patients. Addict Behav. 2008; 33 (2): 292-300. [ Links ]

24. World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview: Version 2.1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. [ Links ]

25. Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. 1992. [ Links ]

26. Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000; 68 (1): 134-44. [ Links ]

27. Young RM, Kavanagh DJ. The Cannabis Expectancy Profile (CEP). Brisbane: University of Queensland. 1997. [ Links ]

28. Connor JP, Gullo MJ, Feeney GF, Young RM. Validation of the Cannabis Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ) in adult cannabis users in treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011; 115 (3): 167-74. [ Links ]

29. Dohrenwend BS, Krasnoff L, Askenasy AR, Dohrenwend BP. Exemplification of a method for scaling life events: The PERI Life Events Scale. J Health Soc Behav. 1978; 19 (2): 205-29. [ Links ]

30. Moos RH, Moos RH. Family Environment Scale Manual. Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1992. [ Links ]

31. Phillips MR, West CL, Shen Q, Zheng Y. Comparison of schizophrenic patients' families and normal families in China, using Chinese versions of FACES-II and the Family Environment Scales. Fam Process. 1998; 37 (1): 95-106. [ Links ]

32. Lehman AF. Quality of LifeToolkit. Cambridge (MA): Health Services Research Institute;. 1995. [ Links ]

33. Gupta N, Mattoo SK, Basu D, Lobana A. Psychometric properties of quality of life (QLS) scale: A brief report. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000; 42 (4): 415-20. [ Links ]

34. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982; 8 (3): 470-84. [ Links ]

35. Ventura J, Nuechterlein K, Subotnik KL, Gutkind D, Gilbert EA. Symptom dimensions in recent-onset schizophrenia and mania: A principal components analysis of the 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 2000; 97 (2-3): 129-35. [ Links ]

36. Cleary M, Hunt GE, Matheson S, Siegfried N, Walter G. Psychosocial treatment programs for people with both severe mental illness and substance misuse. Schizophr Bull. 2008; 34 (2): 226-8. [ Links ]

37. Carr JA, Norman RM, Manchanda R. Substance misuse over the first 18 months of specialized intervention for first episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009; 3(3): 221-5. [ Links ]

38. Addington J, Addington D. Impact of an early psychosis program on substance use. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2001; 25 (1): 60-7. [ Links ]

39. Hinton M, Edwards J, Elkins K, Harrigan SM, Donovan K, Purcell R, et al. Reductions in cannabis and other illicit substance use between treatment entry and early recovery in patients with first-episode psychosis. Ear Inter Psychiatry. 2007; 1: 259-266. [ Links ]

40. Harrison I, Joyce EM, Mutsatsa SH, Hutton SB, Huddy V, Kapasi M, et al. Naturalistic follow-up of co-morbid substance use in schizophrenia: The West London first-episode study. Psychol Med. 2008; 38 (1): 79-88. [ Links ]

41. Maisto SA, Carey KB, Carey MP, Purnine DM, Barnes KL. Methods of changing patterns of substance use among individuals with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999; 17 (3): 221-7. [ Links ]

42. Lobbana F, Barrowclough C, Jeffery S, Bucci S, Taylor K, Mallinson S, et al. Understanding factors influencing substance use in people with recent onset psychosis: A qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 70 (8): 1141-7. [ Links ]

43. Addington J, Duchak V. Reasons for substance use in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997; 96 (5): 329-33. [ Links ]

44. Dekker N, de Haan L, van den Berg S, de Gier M, Becker H, Linzen DH. Cessation of cannabis use by patients with recent-onset schizophrenia and related disorders. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2008; 41 (1): 142-53. [ Links ]

45. Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Dawe S, Young RM. The influence of cannabis use expectancies on cannabis use and psychotic symptoms in psychosis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009; 28 (3): 250-6. [ Links ]

46. Wade D, Harrigan S, Edwards J, Burgess PM, Whelan G, McGorry PD. Patterns and predictors of substance use disorders and daily tobacco use in first-episode psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005; 39 (10): 892-8. [ Links ]

47. Cuffel BJ, Chase P. Remisison and relapse of substance use disorders in schizophrenia. Results from a one-year prospective study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994; 182 (6): 342-8. [ Links ]

48. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6th ed. New York: HarperCollins; 2012. [ Links ]

49. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, McHugo GJ. A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occuring substance use disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004; 27 (4): 360-74. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Shane Rebgetz

Locked Mail Bag 4

Caboolture Queensland Australia 4510

Telephone: +61 7 5316 3100 (Australia)

Fax: +61 7 5499 3171 (Australia)

E-mail: shane.rebgetz@health.qld.gov.au

Received: 4 Juny 2014

Revised: 8 October 2014

Accepted: 15 October 2014