Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.30 no.3 Zaragoza jul./sep. 2016

Psychological and behavioral problems in children of war veterans with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Martina Krešić Ćorića; Miro Klarića; Božo Petrova; Nina Mihićb

a Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of Mostar, Mostar. Bosnia and Herzegovina

b Faculty of Health Studies, University of Mostar, Mostar. Bosnia and Herzegovina

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) caused by war trauma experiences affects veterans'; ability to meet their parental obligations, which can lead to the appearance of psychological and behavioral problems in their children. We explored, based on the parents'; assessment, whether the children of veterans with PTSD exhibit more psychological and behavioral problems and whether there are differences in relation to the age and sex of the child.

Methods: The study group consisted of 91 children from 50 veterans receiving treatment for the war-related PTSD at the Psychiatric Department of the University Clinical Hospital Mostar. The control group consisted of 98 children of 50 war veterans without PTSD who were selected from veteran associations by the snowball method. The following instruments were used in the study: General Demographic Questionnaire, Harvard Trauma Questionnaire-Bosnia and Herzegovina version and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire for children.

Results: Children of veterans with PTSD have more pronounced psychological and behavioral problems (U = 2372.5; P < 0.001) compared to the children of veterans without PTSD. Male children of veterans with PTSD have more frequent behavioral problems (χ2 = 7.174; P = 0.025) compared to the female children, and overall, they more frequently exhibit borderline or abnormal psychological difficulties (χ2 = 6.682; P = 0.029). Children exhibiting abnormal levels of hyperactivity are significantly younger than children who exhibit normal or borderline levels of hyperactivity (Kruskal-Wallis = 3.982; P = 0.046).

Conclusions: The children of war veterans with PTSD have more psychological and behavioral problems in comparison with the children of veterans without PTSD.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder; War; Veterans; Children.

Introduction

Childhood and adolescence are particularly sensitive developmental stages of life1, and disturbances experienced in these stages are important for later upbringing, socialization and successful functioning in adulthood. Growing up in aggressive, stressful and unpredictable family environments can have negative consequences in the future lives of those children2. One such milieu is most certainly the family environment of veterans suffering from PTSD3. More specifically, a number of previous studies have found that close contacts and emotional connection with traumatized persons can become a chronic stressor, and that family members often experience symptoms of trauma and a wide range of psychological distress3,4. Veterans suffering from PTSD, in addition to their personal trauma, due to the often present difficulties in controlling aggressive impulses5,6, and impaired occupational and social functioning7, may have observable difficulties in relationships with their spouse and children4,8,9. Withdrawal, isolation, inability to express emotions10,11, and overprotection and overcontrol of their children12 are only some of the difficulties veterans encounter while trying to function within the family system. In such family environments, important developmental processes of children are especially disturbed, such as the sense of attachment, separation and individualization, due to the fact that the sick parent puts the child in an atmosphere of high anxiety, depression and impulsivity4. According to previous research, children of veterans with PTSD, compared to those veterans without PTSD have more developmental, behavioral and emotional difficulties9, and are about twice as likely to develop serious mental health problems12. These children are more aggressive, hyperactive13, have pronounced depression and somatization symptoms14, and more often engage in delinquent behavior and drug use15. Clinical studies have shown that family dysfunction is a significant predictor of emotional problems12, non-suicidal self-injury16 and suicide attempts in adolescent children of veterans with PTSD17. It was also discovered that children of veterans suffering from PTSD are more likely to seek professional help and have dietary, academic and communication problems18, and some children may also develop secondary traumatic stress19.

Given the degree of individual and social traumatization caused by the war trauma and post-war social situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, we have assumed that the war-related PTSD in veteran population would have a major impact on the incidence of psychological and behavioral problems in their children. The aim of this study is to determine whether children of veterans with PTSD compared to those of veterans without PTSD have more psychological and behavioral problems and whether there are differences in relation to age and sex of the child.

Participants and methods

Participants

The study group consisted of 91 children (from 3-16 years of age) of 50 war veterans receiving treatment at the Psychiatric Department of the University Clinical Hospital Mostar for PTSD caused by combat psychotrauma. The control group consisted of 98 children of 50 war veterans who were not diagnosed with PTSD and who reside in the Herzegovina-Neretva and West Herzegovina Counties.

Methods

The creation of both groups went through several phases. Veterans were the starting point in the creation of the sample population. The necessary criteria for the study group were previously established clinical diagnosis of PTSD. Another requirement was that the veteran had children ranging in age from 3-16 years old. Exclusion criteria were an already established presence of mental illness for which the veteran was treated prior to the war and veteran's status as a single father.

Applying the order in which they responded to participate in the study, veterans who fulfilled these criteria were informed by the principal researcher and his associates about the purpose of this study. Those veterans who have accepted to participate received "Research Notification" and "Consent to Participate." Once they have studied the "Research Notification" and signed "Consent to Participate", veterans were given a battery of tests which consisted of a self-evaluation scale regarding their children. The battery of tests veterans received from the researches were filled out at home, with input from their spouses. During this time, the principal investigator and his associates have provided the participants with the possibility of constant direct phone contact, according to their needs.

While creating the study group, the researchers contacted 94 veterans with previously established PTSD diagnosis. Of the total number of veterans, two veterans (2.1%) had clinically diagnosed mental disease that was treated prior to the war, 22 veterans (23.4%) did not have any children ranging in age from 3-16 years, seven (7.4%) were single fathers, and 13 (13.8%) had not signed "Consent to Participate". After exclusion of these 44 (46.8%) veterans, the final sample of the study group consisted of 50 veterans and their 91 children.

Veterans in the control group were initially recruited through the veterans' organizations, and then by using the snowball method20. In addition to not having been diagnosed with PTSD, other excluding criteria for this group were the existence of a mental disorder for which the veteran was treated prior to the war and the veterans's status of a single father. With prior agreement from the representatives of associations of war veterans in Herzegovina-Neretva and West Herzegovina Counties, the principal researcher made a one-day visit to the association's head-quarters, contacted gathered veterans, distributed "Research Notification" and explained the purpose of the research, asking for their consent to participate. The researcher also asked the veterans to spread the word to their fellow veterans who are not single parents, and who have children between 3-16 years of age, while providing them with a copy of the previously prepared "Research Notification" and asking them to participate in the study. Veterans who have accepted to participate in the survey contacted the principal researcher or his associates by phone and, as agreed over the phone, reported to the Psychiatric Department of the University Clinical Hospital Mostar, or alternatively, the researcher would visit the veterans' association at the previously agreed upon time. Veterans who accepted to participate and signed the "Consent to Participate" have been administered Part IV of the HTQ questionnaire21, which contains questions about post-traumatic symptoms. If the results indicated the existence of PTSD, veterans were excluded from the study. Other respondents were included in further research, using the same battery of tests and the same steps as the study group. Based on the results of HTQ testing, 15 (23.1%) out of 65 veterans met the criteria for PTSD diagnosis, and they were eliminated from the research.

Instruments

General Demographic Questionnaire designed for the purpose of this study which included general demographic data on veterans and their children (first and last name, age, sex).

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire - Bosnia and Herzegovina Version is a measuring instrument exploring various traumatic and emotional disturbances that are thought to be directly associated with the trauma. It consists of four sections. For the purposes of this study we have used: the list of possible traumatic events (part I) and the list of issues relating to the psychosocial problems caused by the trauma (Part IV). The instruments were produced in 1998 jointly by the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma with input from associations for protection of mental health as well as psychiatric experts from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia (Harvard Trauma Manual Bosnia and Herzegovina Version, produced by the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma)21. HTQ is administred in the form of an interview, and in the post-war period it was used in the series of studies of war psychotrauma in the former Yugoslavia9,22,23.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-Cro) - A short questionnaire for children between the ages of 3-16, intended to assess emotional and behavioral problems. A significant feature of the survey is that it focuses on assessing the strengths, not only difficulties in the behavior of children and youth. The questionnaire consisted of five sub-scales, where one of them referred to the strengths of the child (prosocial behavior), while the remaining four measured various degrees of problematic behavior of the child (emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity and peer relationship problems). Each of the mentioned subscales consisted of five psychological attributes. There are several versions of the questionnaire. This study used questionnaires that are usually completed by parents of children from 4-16 years of age, while children from 3-4 years of age were subjected to an adapted questionnaire, which featured 22 identical particles, and two particles related to anti-social behavior which have been modified and adapted to that age. The range of answers to each question included three response categories ("not true", "somewhat true","completely true"). Subscales were scored in such a way that the response "somewhat true" was always awarded one point, but marking "not true" and "completely true" would vary depending on the segment. For each of the five subscales, provided that all five segments were filled out, the result could range from 0-10. A higher score on the questionnnaire assesing the child's strenghts indicates a more positive prosocial behaviour, while a higher score on the remaining four subscales indicated major difficulties. Subscale results can be comparatively evaluated as long as the subjects filled out at least three particles. Total difficulties score is obtained by adding up the results of all the subscales, excluding the "prosocial behavior" subscale. The result can range from 0-40 (and is considered to be volatile if it is missing results from one of the subscales). Although the results of the SDQ can often be used as a whole, it is sometimes convenient to classify the results in three categories, according to the level of symptoms, as normal, borderline and abnormal. Abnormal scores on one subscale or on the total difficulties score can be used to identify probable cases with mental problems24.

Statistical methods of data processing

Statistical tests for data processing are selected depending on the type of variables. The χ2 test was used for nominal and ordinal variables. In absence of the expected frequency, Fisher exact test and Yates correction were applied. In unsymmetrical distribution of data, the researchers utilized the Mann Whitney U test for comparison of two independent variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for comparison of more than two independent variables. SPSS for Windows (version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Microsoft Excel (11th version of the Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) were used for statistical analysis.

Results

Demographic characteristics and differences between veterans' children in the study group and the control group

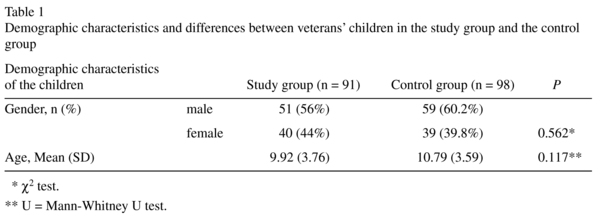

The study group consisted of 51 (56%) boys and 40 (44%) girls, and the control group consisted of 59 (60.2%) boys and 39 (39.8%) girls. There was no statistically significant difference between children of observed groups regarding gender (χ2 test = 0.336; P = 0.562). The average age of children for the study group was M = 9.92 SD = 3.76, versus control group M = 10.79 SD = 3.59, hence there was no statistically significant difference between the observed groups in terms of age (Mann Whitney U = 3872.000; P = 0.117) (Table 1).

Differences in the frequency of psychological and behavioral problems in children of war veterans between the study and control group according to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-Cro)

Of the total number of children, four children in the study group were 3-year-olds for which one of the parents filled out a customized version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ 3-4), and the SDQ questionnaire was not properly filled out on all scales for four children between 4-16 years old. The control group had three 3-year-olds. The results of those children were excluded from the results. The final number of children amounted to 83 in the study group and 95 in the control group.

Using Strengths and Difficulties (SDQ-Cro) Questionnaires for children aged 4-16 years, children of veterans in the study group, when compared to the children of veterans in the control group, showed more pronounced emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, problems in peer relationships, more positive prosocial behavior, and a higher Total difficulties score (Table 2).

Comparison of psychological and behavioral problems regarding sex and age of veterans' children belonging to the study group

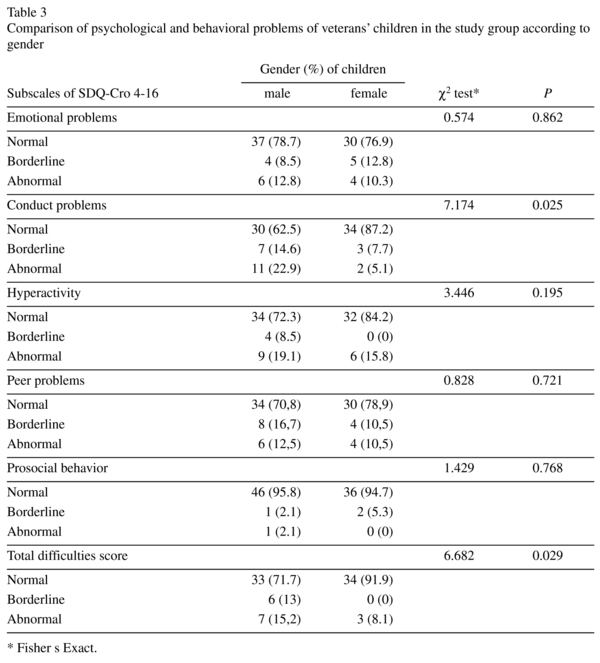

Data from Questionnaire SDQ-Cro 4-16 were classified into three categories according to the level of symptoms, and the results were compared in relation to the sex of veterans'children in the study group. The results indicated that male children had more frequent conduct problems (χ2 test = 7.174; P = 0.025) than female, therefore the totaldifficulties score in male children was frequently more borderline and abnormal than in female children (χ2 test = 6.682; P = 0.029).

While comparing the level of emotional symptoms, hyperactivity, problems in peer relationships and prosocial behavior, there was no statistically significant difference regarding sex of the veterans' children in the study group (Table 3).

Analyzing data questionnaire SDQ-Cro 4-16 in relation to the age of the children revealed that the children with abnormal levels of hyperactivity were significantly younger than the children who had normal or borderline levels of hyperactivity (Kruskal-Wallis = 3.982; P = 0.046). Taking into account emotional symptoms, conduct problems and problems in relationships with peers, prosocial behavior and thetotal difficulties score, there was no statistically significant difference between three levels of symptom manifestationwhen it comes to the sex of children (Table 4).

Discussion

According to the assessment of one of the parents, children of veterans with PTSD have more pronounced psychological and behavioral problems when compared to children of veterans without PTSD. The findings of this study indicate the existence of interconnectedness between veterans' PTSD and psychological and behavioral problems in their children, and is consistent with findings of a series of previous studies4,9,12,25.

Family life with veterans suffering from PTSD can especially negatively impact the development of their children9,12. Exposure of children to stressful intrafamilial atmosphere can increase their vulnerability for development of psychological problems due to their loss of faith in parental relations and security provided by the family environment2. Veterans' poor anger management skills, along with anger outbursts, aggression, and even domestic violence and physical abuse of children, are just some of the characteristics of this atmosphere26,27. Family conflicts and violence may be linked to indifference and lack of parental warmth towards children, neglect, and unstable attachment2 which is the basis for the development of children's emotional symptoms and behavioral problems12,28,29.

Normal development in childhood and adolescence requires regulating of distance/closeness from the parents to enable formation of a separate identity1, which is difficult to achieve in the unstable family environment of PTSD veterans. The physical presence of veteran with PTSD, his psychological absence due to preoccupation with trauma, as well as difficulties in justifying his behavior, can confuse children and lead to disappointment and loss of their respect towards him10. Long-term undefined/missing role of the father in the family leads to confusion regarding boundaries and roles within the family, redistribution of function from father to mother and/or children and emotional distress in the rest of the family3,4. In such situations, children may feel responsible for their father's emotional state, suffer from low self-esteem, lose spontaneity and interest in daily activities, which increases the risk for continuation of such behavioral patterns even in adulthood30,31.

Recently conducted research in the region has also confirmed that children of veterans suffering from PTSD have more pronounced internalized and externalized problems25. Significant predictor of those children's difficulties is a dysfunctional family situation, paternal overcontrol/overprotection and and low maternal and paternal care12.

Although most previous studies found behavioral problems in children of veterans with PTSD9,12,28, the results of this study indicate that, according to the parents' estimates, children of veterans with PTSD have more positive prosocial behavior than children of veterans without PTSD. This could be explained by the fact that parents may be busy with their own suffering, and thus less likely to observe internalized problems in their children. Tense, depressed children of veterans with PTSD often exhibit controlled behavior which can lead to more pronounced prosocial behavior while their suffering and pain remain undetected by those who should provide them with protection and assistance32.

These observations emphasize the interpersonal nature of trauma and can help explain the impact that veterans suffering from PTSD have on the development of children, which ultimately may have far-reaching negative effects on the formation of their personality.

Comparison of psychological and behavioral problems in children of veterans with PTSD regarding gender and age

The findings of this research show that male children of veterans with PTSD exhibit behavioral problems more frequently than female children, and are more likely to exhibit borderline or abnormal overall difficulties. This finding can at least partly be explained by the socialization process and adoption of gender roles. According to previous research, different aspects of quality of family interactions are associated with different psychological problems in children of different sexes33. Our finding that male children are more affected by their father's illness supports "Identification hypothesis"34. Through the process of identification, a male child can start to feel and behave like the veteran with PTSD in order to get closer to him. Such a child may show many of the same symptoms as a veteran with PTSD35,36. Rosenheck34 emphasizes that the degree of identification depends on the quality of parent-child relationship and that children who have a closer relationship with their fathers develop the most similar and most difficult symptoms.

Although very little work has directly evaluated mechanisms of transmission, there is increasing support for genetic and epigenetic effects as well as parenting behaviors28. The system of mirror neurons in the ventral premotor cortex, which is involved in the performance of activities and the observation of behavior of others, also plays a significant role in the development of psychopathology in children of veterans suffering from PTSD, because of its role in imitating behavior37.

The findings of this study also indicate that children with elevated (abnormal) levels of hyperactivity are significantly younger than children who exhibit normal or borderline levels of hyperactivity. The findings suggests that young children of veterans with PTSD are more susceptible to the emergence of distress, and the causes for this are likely due to their limited understanding of their complex intrafamilial situation, due to the fact that these children have not developed the cognitive ability which would enable them to process intrusive and disturbing experiences29,38. The effects of trauma affect their experience of themselves, a sense of the world around them and their self-regulatory capabilities39,40.

While interpreting the results obtained in this study we should take into account the specific methodological limitations. First of all, it is a relatively small sample, which makes it more difficult to apply the results on a broader population. Secondly, there were no self-assessment psychometric instruments that would enable the children to report their own perceived problems. Future research should be more comprehensive, including the children's self-assessment of the occurrence of psychological problems and disorders of behavior that may result from disturbed family relationships, along with the assessment of the objective observer (parent, teacher). In addition to this, there was no assessment of the extent of the trauma for the mother, as well as the impact of her trauma on the family dynamics and functionality, emergence of psychological and behavioral problems in children, and in particular, the consequences on the children when both parents have been traumatized.

Conclusion

Veterans suffering from PTSD have a significant impact on the occurrence of psychological and behavioral problems in their children. This set of data suggests the need for early identification and treatment of the traumatized families, to prevent far-reaching negative effects on growth and development of the affected children.

References

1. Wenar C, Kerig P. Developmental psychopathology: from infancy through adolescence (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. [ Links ]

2. Cummings EM, Davies PT: Marital conflict and children: an emotional security perspective New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [ Links ]

3. Galovski T, Lyons JA. Psychological sequelae of combat violence: a review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran's family and possible interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004; 9: 477-501. [ Links ]

4. Dekel R, Goldblatt H. Is there intergenerational transmission of trauma? The case of combat veterans' children. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008; 78(3): 281-9. [ Links ]

5. Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Fairbank JA, Schlenger WE, Kulka RA, Hough RL, et al. Problems in families of male Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992; 60(6): 916-26. [ Links ]

6. Taft CT, Street AE, Marshall AD, Dowdall DJ, Riggs DS. Posttraumatic stress disorder, anger, and partner abuse among Vietnam combat veterans. J Fam Psychol. 2007; 21(2): 270-7. [ Links ]

7. Davidson AC, Mellor DJ. The adjustment of children of Australian Vietnam veterans: is there evidence for the trans-generational transmission of the effects of war-related trauma? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001; 35: 345-51. [ Links ]

8. Gewirtz AH, Polusny MA, DeGarmo DS, Khaylis A, Erbes CR. Posttraumatic stress symptoms among National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq: associations with parenting behaviors and couple adjustment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010; 78(5): 599-610. [ Links ]

9. Klarić M, Francisković T, Klarić B, Kvesić A, Kastelan A, Graovac M, et al. Psychological problems in children of war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder in Bosnia and Herzegovina: cross-sectional study. Croat Med J. 2008; 49(4): 491-8. [ Links ]

10. Ruscio AM, Weathers FW, King LA, King DW. Male war-zone veterans' perceived relationships with their children: the importance of emotional numbing. J Trauma Stress. 2002; 15(5): 351-7. [ Links ]

11. Samper RE, Taft CT, King DW, King LA. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and parenting satisfaction among a national sample of male vietnam veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2004; 17(4): 311-5. [ Links ]

12. Boricevic Marsanic V, Aukst Margetic B, Jukic V, Matko V, Grgic V. Self-reported emotional and behavioral symptoms, parent-adolescent bonding and family functioning in clinically referred adolescent offspring of Croatian PTSD war veterans. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014; 23(5): 295-306. [ Links ]

13. Parsons J, Kehle TJ, Owen SV. Incidence of behavior problems among children of Vietnam veterans. School Psychol Int. 1990; 11: 253-9. [ Links ]

14. Zalihić A, Zalihić D, Pivić G. Influence of posttraumatic stress disorder of the fathers on other family members. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2008; 8(1): 20-6. [ Links ]

15. Beckham JC, Braxton LE, Kudler HS, Feldman ME, Lytle BL, Palmer S. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profiles of Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and their children. J Clin Psychol. 1997; 53(8): 847-52. [ Links ]

16. Boricevic Marsanic V, Aukst Margetic B, Ozanic Bulic S, Duretic I, Kniewald H, Jukic T, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury among psychiatric outpatient adolescent offspring of Croatian posttraumatic stress disorder male war veterans: Prevalence and psychosocial correlates. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015; 61(3): 265-74. [ Links ]

17. Boricevic Marsanic V, Margetic BA, Zecevic I, Herceg M. The prevalence and psychosocial correlates of suicide attempts among inpatient adolescent offspring of Croatian PTSD male war veterans. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2014; 45(5): 577-87. [ Links ]

18. Davidson J, Smith R, Kudler H. Familial psychiatric illness in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1989; 30(4): 339-45. [ Links ]

19. Steinberg A. Understanding the secondary traumatic stress of children. In: Figley CR, ed. Burnout in Families: The Systematic Costs of Caring. New York (NW): CRC Press; 1998. p. 29-46. [ Links ]

20. Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2004; 34: 193-239. [ Links ]

21. HTQ-Harvard Trauma Manual Bosnia-Herzegovina Version, Produced by the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma; 1998. [ Links ]

22. Wenzel T, Rushiti F, Aghani F, Diaconu G, Maxhuni B, Zitterl W. Suicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress and suicide statistics in Kosovo. An analysis five years after the war. Suicidal ideation in Kosovo. Torture. 2009; 19(3): 238-47. [ Links ]

23. Nemcić-Moro I, Francisković T, Britvić D, Klarić M, Zecević I. Disorder of extreme stress not otherwise specified (DESNOS) in Croatian war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: case-control study. Croat Med J. 2011; 52(4): 505-12. [ Links ]

24. SDQ: Information for researchers and professionals about the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaires 2008 (http://www.sdqinfo.com). [ Links ]

25. Sarajlic Vukovic I, Boricevic Marsanic V, Aukst Margetic B, Paradzik LJ, Vidovic D, Buljan Flander G. Self-reported emotional and behavioral problems, family functioning and parental bonding among psychiatric outpatient adolescent offspring of Croatian male veterans with partial PTSD. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2015; 44: 655-69. [ Links ]

26. Harkness L, Zador N. Treatment of PTSD in families and couples. In: Wilson JP, Friedman MJ, Lindy JD, eds. Treating psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford; 2001. p. 335-53. [ Links ]

27. Leen-Feldner EW, Feldner MT, Bunaciu L, Blumenthal H. Associations between parental posttraumatic stress disorder and both offspring internalizing problems and parental aggression within the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. J Anxiety Disord. 2011; 25(2): 169-75. [ Links ]

28. Leen-Feldner EW, Feldner MT, Knapp A, Bunaciu L, Blumenthal H, Amstadter AB. Offspring psychological and biological correlates of parental posttraumatic stress: review of the literature and research agenda. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013; 33(8): 1106-33. [ Links ]

29. Barthassat J. Positive and Negative Effects of Parental Conflicts on Children's Condition and Behaviour. Journal of European Psychology Students. 2014; 5: 10-8. [ Links ]

30. Harkness LL. The Effect of Combat-Related PTSD on Children. National Center for PTSD Clinical Newsletter. 1991; 2: 12-13. [ Links ]

31. Matsakis A. Vietnam Wives. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press; 1996. [ Links ]

32. Dansby VS, Marinelli RP. Adolescent children of Vietnam combat veteran fathers: a population at risk. J Adolesc. 1999; 22(3): 329-40. [ Links ]

33. Schleider JL, Chorpita BF, Weisz JR. Relation between parent psychiatric symptoms and youth problems: moderation through family structure and youth gender. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014; 42(2): 195-204. [ Links ]

34. Rosenheck R, Thomson J. "Detoxification" of Vietnam War trauma: a combined family-individual approach. Fam Process. 1986; 25(4): 559-70. [ Links ]

35. Ancharoff MR, Munroe JF, Fisher LM. The legacy of combat trauma: Clinical implications of intergenerational transmission. In: Danieli Y, ed. International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma New York (NY): Plenum Press; 1998. p. 257-75. [ Links ]

36. Franić T, Kardum G, Marin Prižmić I, Pavletić N, Marčinko D. Parental involvement in the war in Croatia 1991-1995 and suicidality in Croatian male adolescents. Croat Med J. 2012; 53(3): 244-53. [ Links ]

37. Oztop E, Kawato M, Arbib MA. Mirror neurons: functions, mechanisms and models. Neurosci Lett. 2013; 540: 43-55. [ Links ]

38. Dass-Brailsford P. A practical approach to trauma: Empowering interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [ Links ]

39. van der Kolk BA. Developmental trauma disorder: A new, rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals. 2005; 35: 401-8. [ Links ]

40. Arvidson J, Kinniburgh K, Howard K, Spinazzola J, Strothers H, Evans M, et al. Treatment of complex trauma in young children: Developmental and cultural considerations in application of the ARC intervention model. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma. 2011; 4: 34-51. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Martina Krešić Ćorić

Department of Psychiatry

School of Medicine, University of Mostar

Bijeli Brijeg bb 88000 Mostar

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Telephone: 00 387 63 316 545

E-mail: martinakresic5@yahoo.com

Received: 18 January 2016

Revised: 24 April 2016

Accepted: 24 May 2016