Introduction

Environmental and policy interventions based on boosting environments that emphasize healthy behaviours within school-age populations have been identified as the most promising strategies for creating population-wide improvements in dietary and physical activity patterns, as well as weight status.1 These strategies often take place within the school, where children spend considerable daylight time and consume between one-third to one-half of their meals, making this environment critical in forming and reinforcing healthy lifestyle habits.2

Multiple scholars have documented the effectiveness of school-based interventions aimed at nutrition3 and physical activity environments,4,5 yet there is still a dearth of understanding on the actual mechanisms through which those interventions might modify, or not, behavioural patterns at the student level. In this context, several researchers have developed tools for assessing school environments relevant to food and/or physical activity.6,7 Nonetheless, in a recent systematic review of 23 different tools, Lane et al.7 concluded that many of these instruments do not provide enough evidence for its relevance and usability, which lead to an important obstacle for future replication and implementation in other context. Furthermore, they often focused only on one dimension (physical activity or nutrition), or they did not include aspects such as situational or policy environments.7

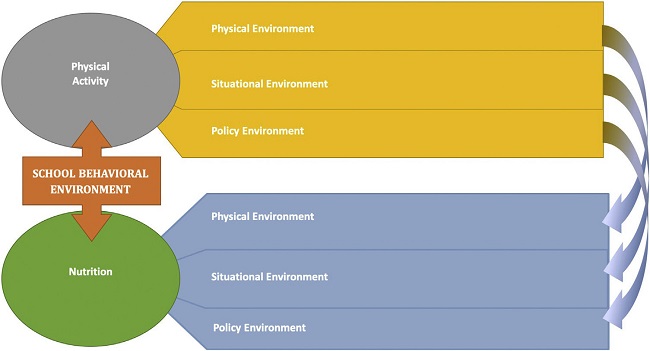

Among the validated tools with both dimensions (physical activity and nutrition), the School Physical Activity and Nutrition Environment Tool (SPAN-ET) stand out among the rest because of its comprehensively assessment of the school environment's role in terms of nutrition and physical activities along three environmental categories: physical, situational, and policy related.8 Using several methods of collecting data and triangulating confirmed data criteria, the SPAN-ET surveys and scores school resources and readiness to improve nutrition and physical activity environments. SPAN-ET was created and validated for the US elementary school context and in English by Oregon State University researchers.8 Despite its methodology and content are relevant, a simple language translation does not make it ready for use in other countries, as legal regulations and cultural contexts might vary among them.

This paper aims at performing a cross-cultural adaptation, content validity and feasibility of SPAN-ET for the Spanish context. By following the guidelines of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) on how to achieve a translation and cultural adaptation, perform a content validation,9 and apply pilot testing, we purvey a full new version of the SPAN-ET in Spanish (SPAN-ET-ES, hereafter).

Method

Baseline instrument: School Physical Activity and Nutrition Environment Tool (SPAN-ET)

The SPAN-ET is a standardized instrument that provides a comprehensive observational assessment of the features, practices, and policies within the school environment that might affect the physical activity and nutrition habits in elementary school children.8 As a result, the SPAN-ET identifies the critical areas within the school that are in need of improvement, specifically the environments that promote healthy nutrition and/or physical activity habits, enhance student learning outcomes, and support core competences of partnerships and learning strategies.8

The SPAN-ET evaluates the school's physical activity and nutrition contexts through 27 items, referred to as “areas of interest” (AI), which are organized within three environmental categories: physical, situational, and policy.Figure 1 visualizes the multidimensional and interactive framework of the SPAN-ET model for quantifying the quality of the school's physical activity and nutrition contexts across the three environmental categories.8

In order to evaluate each AI, the SPAN-ET provides a set of criteria that describes evidence-based best practices for each AI. If a school under evaluation fulfils at least 75% of the set criteria, we can conclude that this institution uses the best practices of this given AI. If, in contrast, it only fulfils 25% or less of the criteria, we conclude that this institution has poor practices. Table I in the online Appendix A shows the entire set of evaluations for each AI or environment.

The set of criteria for each AI might cover different types of aspects that require different types of information. Thereby, the use of the SPAN-ET implies the triangulation of different qualitative and quantitative information using direct observation, photography, interviews, document review, among others. During the school visit, two auditors observe physical and situational environments and interview all informants necessary to adequately assess each AI (Table II in the online Appendix A).

Schools are asked to provide two main sources of information: 1) institutional documentation (secondary data), and 2) interviews of key informants listed in Table II in the online Appendix A (primary data). The two auditors independently code each item. Before doing the interviews and physical visits, the auditors review in detail all the documentation, making an initial assessment of each AI. These data sources are complemented with systematic direct observations of physical and situational environments that are conducted before, during, and after the school day.

After the completion of data collection, auditors review the data, item by item, to identify the level of agreement. When a disagreement occurs between the auditors, they re-review all the available evidence as well as their perceptions to come to an agreement. Thus, the final scoring of a given AI assessment is the result of a consensus between the two auditors. Finally, a comprehensive report is delivered to each school to provide them with a set of recommendations.

Cross-cultural adaptation, content validation, and feasibility

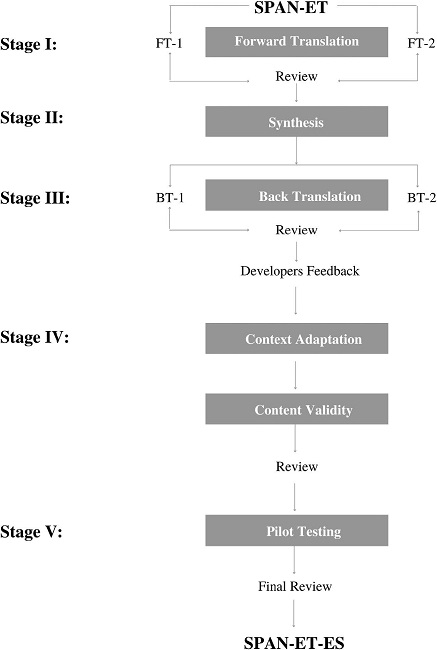

Cross-cultural adaptation was conducted from September 2018 to August 2019. Based on the Guideline for Process of Cross-cultural Adaptation proposed by Beaton et al.,9 we followed a five-stage methodological process that contains the standard stages suggested by the authors as well as a content validity analysis to obtain a better adapted version for the Spanish context. Figure 2 describes each stage. As a result, we provided a new version of the SPAN-ET for the Spanish context, which we have called SPAN-ET-ES. Both the translation and cross-cultural adaptation were conducted using the English version of the SPAN-ET, provided directly by the original developers.

Figure 2. Global schema illustrating the different phases of cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the SPAN-ET questionnaire to the Spanish context. Stages proposed by Beaton et al.9 for cross-cultural adaptation are indicated as Stages I to V. The content validity analysis was performed by a panel of five experts just before the pilot testing. FT, forward translation; BT, back translation.

1) Stages I and II: forward translation and synthesis

The first step for the cross-cultural validation was the initial translation from English into Spanish. In order to identify translation discrepancies and the absence of equivalent wording in specific questions as well as other theoretical or cultural differences, two independent translators with proficient English and different backgrounds were selected.9 Our research team compared the translations in order to identify the main agreements and disagreements. In most cases, both translators agreed on the wording and phrasing of the translation. The SPAN-ET developers clarified a few disagreements in the Spanish translation. After their feedback and discussion, the synthesis version of the SPAN-ET-ES was completed.

2) Stage III: back translation

Thereafter, two independent professional English translators with no knowledge of the original SPAN-ET were asked to translate the SPAN-ET-ES back from Spanish to English. These two new versions of the SPAN-ET were again reviewed and refined. The reviewed version was sent to the original developers to analyse the accuracy and proximity of this new version with respect to the original. Based on the final feedback and discussion, a second version of the SPAN-ET-ES was concluded.

3) Stage IV: context adaptation

Starting with the new version, our research team performed a comprehensive context adaptation in two main areas. In the first area, as the original instrument was based on US legislation, we used the Spanish regulation counterpart. In the second area, we incorporated the Spanish equivalences of all references related to the US education system. All these adaptations required an extensive revision of Spanish legislation, regulations, and guides on different issues and, in some cases, their comparison with their US counterparts. All the literature consulted can be found in the Appendix B online.

After the context validation, SPAN-ET-ES was tested to assess the level of comprehensibility, applicability, and cultural appropriateness in the Spanish context. To do this, we performed a content validity analysis10 where a panel of five experts with different backgrounds were invited to evaluate each AI of the SPAN-ET-ES11,12. Using a four-point scale, each expert was asked to evaluate four dimensions of each AI: relevance, clarity, simplicity, and ambiguity (Table 1).

Table 1. Criteria for measuring content validity.10.

| Four-point scale for the content validity index | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Relevance | |||

| Not relevant | Item needs some revisions | Relevant but needs minor revisions | Very relevant |

| Clarity | |||

| Not clear | Item needs some revisions | Clear but needs minor revisions | Very clear |

| Simplicity | |||

| Not simple | Item needs some revisions | Simple but needs minor revisions | Very simple |

| Ambiguity | |||

| Ambiguous | Item needs some revisions | No doubt but needs minor revisions | Meaning is clear |

The panel of experts was made up of five professionals from different fields: a doctor in Physical Activity and Exercise Sciences specialized in motor learning in childhood, a doctor in Food Science and Technology specialized in Food Hygiene, a dietitian and doctor in medicine specialized in collective catering a dietitian-nutritionist responsible for the program for the revision of school menus of the Generalitat de Catalunya, and a dietitian and anthropologist specialized in nutrition in childhood and adolescence.

Based on the expert assessment, we computed the content validity of each individual item (I-CVI), which is the share of experts giving a rating of either 3 or 4 for each dimension:12

Once the I-CVI was calculated for each AI, we estimated an aggregated approach of content validity by environment and by the entire instrument.13 For doing this, we estimated the content validity of the overall scale average (S-CVI/Ave):

We developed an online tool using Open Data Kit 8 (opendatakit.org) in order to facilitate the review by the experts. Once collected, the information was analysed using Stata 14 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA).

4) Stage V: pilot testing

Once the new version of the SPAN-ET-ES was obtained from the content validity analysis, we performed a pilot test. This was carried out in Santa Coloma de Gramenet, a city close to Barcelona, in Catalonia, Spain. According to the latest national registry in 2019,14 Santa Coloma was estimated to have 119,215 inhabitants and have a per capita gross income of €22,539 per capita. In total, we visited five public schools (four public schools and one sponsored by a public voucher system). Two well-trained researchers performed the evaluations, following the guidelines provided by the original developers.8

Results

SPAN-ET translation and cross-cultural adaptation

After the forward and back translations were done, a revised version was discussed with the original developers who agreed on the new wording and re-rephrasing. Once our research team had the certainty that the SPAN-ET-ES preserved the main dimensions of the original instrument, the context adaptation was performed in order to make the SPAN-ET-ES compatible with the legislation and other particularities of the Spanish context. In this process we added three items and deleted one. First, in order to gather information about the participation in various physical activity programs,15-17 we included a new item in AI-12 (Table 2). Additionally, we added two items in AI 16 and AI 27 that refer to the use of new technologies and their potential effects on the physical activity (AI-16) and nutrition (AI-27) of children. Second, as the item related to the presence of a health and nutrition educator did not apply to the Spanish context, we deleted item H in AI-27.

Table 2. Number of items and changes made to them during the translation and cross-cultural validation process for the SPAN-ET-ES.

| Content | SPAN-ET (items) | SPAN-ET-ES (items) | Changes made | Main modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | 106 | 108 | ||

| Physical environment | 50 | 50 | ||

| AI 1: Indoor physical activity space | 15 | 15 | 8 | Legislation and phrasing |

| AI 2: Fixed-outdoor features/space | 9 | 9 | 3 | |

| AI 3: Shelter and shade structures | 3 | 3 | ||

| AI 4: Natural features | 4 | 4 | ||

| AI 5: Garden features | 3 | 3 | ||

| AI 6: Surface and surface markings | 4 | 4 | 1 | Cultural context |

| AI 7: Enclosures and safety features | 7 | 7 | 4 | Legislation |

| AI 8: Neighbourhood features | 5 | 5 | 1 | Phrasing |

| Total | 17 | |||

| Situational environment | 32 | 33 | ||

| AI 9: Portable equipment | 5 | 5 | ||

| AI 10: Atmosphere/ambiance | 7 | 7 | ||

| AI 11: Promoting movement opportunities | 6 | 6 | ||

| AI12: Before/after school and summer extracurricular | 11 | 12 | 1 | Item added |

| AI 13: Gardening | 3 | 3 | ||

| Total | 1 | |||

| Policy environment | 24 | 25 | ||

| AI 14: Physical activity and wellness policy | 10 | 10 | 1 | Legislation and cultural context |

| AI 15: Physical activity and wellness committee | 5 | 5 | ||

| AI 16: Structured physical education | 9 | 10 | 2 | Cultural context; item added |

| Total | 3 | |||

| Total for physical activity | 21 | |||

| Nutrition | 81 | 81 | ||

| Physical environment | 7 | 7 | ||

| AI 17: Cafeteria/meal service area | 5 | 5 | ||

| AI 18: Garden features | 2 | 2 | ||

| Total | 0 | |||

| Situational environment | 46 | 46 | ||

| AI 19: School meals | 9 | 9 | 2 | Legislation and cultural context |

| AI 20: Promoting healthy food and beverage habits | 7 | 7 | 1 | Legislation |

| AI 21: Healthy food and beverage practices | 5 | 5 | 2 | Legislation and cultural context |

| AI 22: Promoting water consumption | 8 | 8 | 1 | Phrasing |

| AI 23: Cafeteria atmosphere/ambiance | 10 | 10 | 1 | Cultural context |

| AI24: Before/after school and summer extracurricular | 7 | 7 | 1 | Legislation and phrasing |

| Total | 8 | |||

| Policy environment | 28 | 28 | ||

| AI 25: Nutrition and wellness policy | 15 | 15 | 5 | Legislation, cultural context, and phrasing |

| AI 26: Nutrition and wellness committee | 5 | 5 | ||

| AI 27: Health and nutrition education | 8 | 8 | 4 | Legislation and cultural context; one item added and one suppressed |

| Total | 9 | |||

| Total for nutrition | 17 |

Furthermore, the new version underwent small changes in format, phrasing, and content, in order to simplify its application in Spain. In total, we made 38 changes throughout the instrument; no changes were made to the answer scale (Table 2). A detailed report on the changes are available upon request. An example of an extract of preliminary instructions and some AI translated to Spanish can be found in the Appendix C and Appendix D online.

Content validity analysis

After the translation and cross-cultural adaptation process, as well as the feedback from and discussion with the original developers, a content validity analysis was performed. Overall, the expert panel considered that, on average, items included in the revised version of the SPAN-ET-ES were found relevant (S-CVI/Ave=0.96), clear (S-CVI/Ave=0.96), simple (S-CVI/Ave=0.98), and non-ambiguous (S-CVI/Ave=0.98). When looking at the environmental level, we found that whereas the AI contained within the physical activity environment was considered very relevant, we had to implement minor changes to four AIs (relevance CVI <0.8) within the nutrition environment, as the experts considered them not applicable to the Spanish context. Table 3 summarizes the content analysis results for the SPAN-ET-ES.

Table 3. Overall scale average (S-CVI/Ave) for each area of interest in the SPAN-ET-ES.

| Items | Relevance I-CVI | Clarity I-CVI | SimplicityI-CVI | Ambiguity I-CVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Physical environment | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 1: Indoor physical activity space | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 2: Fixed-outdoor features/space | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 3: Shelter and shade structures | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 4: Natural features | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 5: Garden features | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| AI 6: Surface and surface markings | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 7: Enclosures and safety features | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 8: Neighbourhood features | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Situational environment | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 9: Portable equipment | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 10: Atmosphere/ambiance | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 11: Promoting movement opportunities | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 12: Before/after school and summer extracurricular | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 13: Gardening | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Policy environment | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| AI 14: Physical activity and wellness policy | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 15: Physical activity and wellness committee | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| AI 16: Structured physical education | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Nutrition | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Physical environment | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 17: Safe and adequate cafeteria/meal service area | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 18: Garden features | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Situational environment | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 19: School meals | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 20: Promoting healthy food and beverage habits | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| AI 21: Healthy food and beverage practices | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 22: Promoting water consumption | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| AI 23: Cafeteria atmosphere/ambiance | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 24: Before/after school and summer extracurricular | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Policy environment | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| AI 25: Nutrition and wellness policy | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AI 26: Nutrition and wellness committee | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| AI 27: Health and nutrition education | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Overall (S-CVI/Ave) | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

Pilot testing

Table 4 presents the results of the SPAN-ET-ES pilot testing phase for five Spanish schools located in Santa Coloma de Gramenet. Following the SPAN-ET-ES field work guidelines, the two trained auditors collected the documentation needed to assess the 27 AIs for each school. In all cases, they confirmed the existence of each data source as well as its accessibility. Besides small changes for the field work guidelines, the SPAN-ET-ES is based on information that is available in the Spanish context, which allows for a proper assessment of each AI. The auditors also indicated that the items included in the different AIs were easily understandable. On average, contacting schools, collecting, organizing, assessing the agreement and analyzing all the required information (primary and secondary data) for the SPAN-ET-ES took around 15 hours per school.

Table 4. Level of accomplishment of each item and area of interest after applying the SPAN-ET-ES to the pre-pilot sample.

| School 1 | School 2 | School 3 | School 4 | School 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity | |||||

| Physical Environment | Fair Practice | Good Practice | Good Practice | Fair Practice | Fair Practice |

| AI 1: Indoor Physical Activity Space | 0/15 (0%) | 13/15 (87%) | 11/15 (73%) | 0/15 (0%) | 12/15 (80%) |

| AI 2: Fixed-Outdoor Features/Space | 4/9 (44%) | 4/9 (44%) | 4/9 (44%) | 3/9 (33%) | 2/9 (22%) |

| AI 3: Shelter and Shade Structures | 1/3 (33%) | 0/3 (0%) | 3/3 (100%) | 1/3 (33%) | 0/3 (00%) |

| AI 4: Natural Features | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 1/4 (25%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/4 (00%) |

| AI 5: Garden Features | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 1/3 (33%) | 2/3 (67%) | 1/3 (33%) |

| AI 6: Surface and Surface Markings | 2/4 (50%) | 2/4 (50%) | 1/4 (25%) | 2/4 (50%) | 1/4 (25%) |

| AI 7: Enclosures and Safety Features | 7/7 (71%) | 7/7 (100%) | 7/7 (100%) | 6/7 (86%) | 7/7 (100%) |

| AI 8: Neighbourhood Features | 1/5 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) |

| Situational Environment | Good Practice | Fair Practice | Good Practice | Good Practice | Good Practice |

| AI 9: Portable Equipment | 1/6 (17%) | 1/6 (17%) | 2/6 (33%) | 5/6 (83%) | 5/6 (83%) |

| AI 10: Atmosphere/Ambiance | 6/7 (86%) | 2/7 (29%) | 4/7 (57%) | 2/7 (29%) | 3/7 (43%) |

| AI 11: Promoting Movement Opportunities | 2/6 (33%) | 2/6 (33%) | 4/6 (67%) | 1/6 (17%) | 3/6 (50%) |

| AI 12: Before/After School and Summer Extracurricular | 10/12 (83%) | 5/12 (42%) | 11/12 (92%) | 10/12 (83%) | 11/12 (92%) |

| AI 13: Gardening | 0/3 (0%) | 1/3 (33%) | 2/3 (67%) | 1/3 (33%) | 1/3 (33%) |

| Policy Environment | Fair Practice | Fair Practice | Fair Practice | Fair Practice | Fair Practice |

| AI 14: Physical Activity and Wellness Policy | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| AI 15: Physical Activity and Wellness Committee | 4/5 (80%) | 0/5 (0%) | 4/5 (80%) | 4/5 (80%) | 4/5 (80%) |

| AI 16: Structured Physical Education | 8/10 (80%) | 8/10 (80%) | 8/10 (80%) | 8/10 (80%) | 8/10 (80%) |

| Nutrition | |||||

| Physical Environment | Good Practice | Good Practice | Best Practice | Best Practice | Good Practice |

| AI 17: Safe and Adequate Cafeteria/Meal Service Area | 4/5 (80%) | 5/5 (100%) | 5/5 (100%) | 5/5 (100%) | 4/5 (80%) |

| AI 18: Garden Features | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/2 (100%) | 2/2 (100%) | 1/2 (50%) |

| Situational Environment | Good Practice | Fair Practice | Good Practice | Good Practice | Good Practice |

| AI 19: School Meals | 5/9 (56%) | 1/9 (11%) | 5/9 (56%) | 5/9 (56%) | 4/9 (44%) |

| AI 20: Promoting Healthy Food and Beverage Habits | 3/7 (43%) | 1/7 (14%) | 3/7 (43%) | 3/7 (43%) | 2/7 (29%) |

| AI 21: Healthy Food and Beverage Practices | 5/5 (100%) | 2/5 (40%) | 2/5 (40%) | 3/5 (60%) | 3/5 (60%) |

| AI 22: Promoting Water Consumption | 5/8 (63%) | 4/8 (50%) | 5/8 (63%) | 3/8 (38%) | 6/8 (75%) |

| AI 23: Cafeteria Atmosphere/Ambiance | 4/10 (40%) | 8/10 (80%) | 6/10 (60%) | 9/10 (90%) | 8/10 (80%) |

| AI 24: Before/After School and Summer Extracurricular | 5/8 (63%) | 0/8 (0%) | 5/8 (63%) | 3/8 (38%) | 2/8 (25%) |

| Policy Environment | Poor Practice | Poor Practice | Poor Practice | Poor Practice | Poor Practice |

| AI 25: Nutrition and Wellness Policy | 0/15 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) |

| AI 26: Nutrition and Wellness Committee | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) |

| AI 27: Health and Nutrition Education | 7/8 (88%) | 4/8 (50%) | 3/8 (38%) | 4/8 (50%) | 4/8 (50%) |

Overall, we found a 93% of agreement in the item scores between the two auditors when evaluating each AI. We only found two main disagreements in AI 1 and 23, which were easily resolved after reviewing complementary data sources. This high level of agreement between auditors was due to previous training in the administration of SPAN-ET-ES and the homogeneity achieved in the evaluation criteria. Table 4 presents the results of the assessment after applying the SPAN-ET-ES to the pilot testing sample.

Discussion

Prior work has documented the effectiveness of school-based interventions for promoting nutrition and physical activity among children and adolescents.3,18 Such programs are developed within complex school behavioural environments which in turn involve physical, situational, and policy environments that can either facilitate or obstruct the effectiveness of any initiative to promote healthy habits among school-age populations.3,8 In this setting, it is important to be able to count on standardized tools that allow for the comprehensive understanding of the complexity of the school environment in its role in supporting healthy nutrition and physical activities. In this study, we adapted and partially validated the SPAN-ET, a tool developed in the US context, to be able to evaluate the school environment in its different contextual dimensions in the Spanish context.

Although we found some studies of cross-cultural translation and adaptation to the Spanish context of instruments related to nutritional outcomes of school age population,19 we did not find previous experiences of tools like the SPAN-ET. In our work on the Spanish version of the SPAN-ET, apart from modifying some criteria phrasing, we have incorporated important changes in some features related to specificities in legislation and the cultural context. These changes are essential because the cross-cultural adaptation includes not only a correct translation that preserves the meaning of each test item, but also, if necessary, replaces items in order to make them relevant and valid in the new context.9,20

Face validity was assessed by our research team at both the cross-cultural adaptation and the review stages.21 Additionally, the extensive literature and documentation review that was done, ensured that all significant aspects in the assessment of nutrition and physical activity environments were included. The final version of the SPAN-ET-ES includes more precise wording in some cases, as well as extensive instructions that also accompanied the original SPAN-ET, which were translated and adapted with the help of the original developers.

Content validity was studied with the collaboration of an expert panel that used content validity indexes to evaluate the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the SPAN-ET-ES's content.21 The results obtained indicated the relevance of the items included. Content validity facilitates the interpretation of the results obtained by the questionnaire and ensures construct validity.

Employing the SPAN-ET-ES in the pilot study confirmed its feasibility in the Spanish context. One important advantage of the SPAN-ET (and its Spanish version) is that it assesses simultaneously the two main school behavioural environments (i.e. nutrition and physical activity), integrates documentation, observations, and interviews with key school actors, and assesses multiple aspects of the physical, situational, and policy environment allowing for a comprehensive description of the school environment.22 Other similar tools do not offer such coverage and describe only some aspects of the school environment,23 rely mainly on interviews with administrators,24 or include only food or physical activity environments.22

In a recent systematic review, Micha et al.3 found that there is strong evidence that nutritional programs and policies such as direct provision policies, competitive food/beverage standards, and school meal standards increasing fruit and vegetable intake, reduce the consumption of unhealthy snacks, as well as reduce total and saturated fat intake. Ridgers et al.5 provide a systematic review of one of the most documented interventions within the school environment: the role of recess on physical activity. These authors conclude that this type of intervention makes a small contribution to daily moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity.

Even though these school-based interventions have well established effects on several outcomes, there is an important lack of understanding on the actual mechanisms through which these interventions produce changes in individual outcomes.3 Likewise, the unintended structural effects produced by a specific intervention on dimensions such as school policies or situational environments, are often neglected in school environment assessment tools.8,25 In this context, the SPAN-ET (and its Spanish version) provides a valuable tool to assess school environments, which can work either as a baseline for an intervention or as an end-line for measuring effects.8 Additionally, the SPAN-ET can be helpful in collecting data to assess school environments and then designing appropriate community policies aimed at improving them. This is the first study to our knowledge that assesses a standardized tool for evaluating school nutrition and physical activity environments in the Spanish context.

The scientific evidence on school-based interventions or assessments of school environments is scarce in Spain. In the framework of diverse initiatives of health promotion in schools led by various international organizations,26 some authors have assessed the implementation of these initiatives in a sample of schools in different regions of Spain.27,28 They had a general health promotion focus and did not evaluate the school environment in detail in the aforementioned aspects. Additionally, some education-based interventions have shown some preliminary evidence of their actual effects on nutrition related to outcomes such as obesity.29,30 None of this research provides any detailed baseline or end-line assessment of the actual conditions of environments within schools, probably due to its difficulty and the lack of adequate tools.

Although this study has completed a proper translation of the SPAN-ET for the Spanish context and included the assessment of some psychometric characteristics, there are some others that still remain undetermined. Additional research is now in process to complete the study of criterion validity, reliability (internal consistency, stability, and inter-auditor agreement), and the establishment of construct validity using a representative sample of Spanish schools. Once this validation process is finished, we will be able to assess the validity of the SPAN-ET-ES for the entire Spanish scholar system. Additional research could also examine the extent to which the use of the SPAN-ET-ES can provide new data for understanding the mechanisms through which school-based interventions could lead to structural transformations within the school.

In sum, the results from the cross-cultural adaptation and content validity analysis, allow us to conclude that SPAN-ET-ES is a feasible tool for assessing nutrition and physical activity environments at schools in the Spanish context. Likewise, our results are limited to the country setting of Spain. In order to use this tool in other Spanish-speaking contexts like those of Latin America, the SPAN-ET-ES should be adapted in terms of language, legislation, and other context-specific characteristics in each dimension, and then correspondingly validated.

What is known about the topic?

It is well stablished the effectiveness of school-based interventions for promoting nutrition and physical activity among children and adolescents. However, there is a lack of standardized tools, especially in non-English speaking countries, that allow a comprehensive understanding of the complexity of the school micro-environment in its role in supporting healthy nutrition and physical activities.

What does this study add to the literature?

This paper reports the cross-cultural adaptation and the validation of the content and feasibility of an instrument for assessing the school micro-environment in the Spanish context, which can work either as a baseline for school-based interventions or as an end-line for measuring effects in promoting the adoption of lifelong healthy habits in school-age populations.

What are the implications of the results?

The SPAN-ET-ES is a new tool that can work either as a baseline for school-based interventions or as an end-line for measuring effects in promoting the adoption of lifelong healthy habits in school-age populations in Spain. Moreover, it might also improve the design of evidenced-based policies and the development of institutional standards for promoting the nutrition and physical activity among Spanish schools.

Transparency declaration

The corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.