The reading of meta-analyses is now common among psychologists. It is often taken for granted that they refer to quantitative studies, although this is not necessarily the case since there are qualitative meta-analyses of various types (Levitt, 2020; Paterson et al., 2001; Zhao, 1991). These are methods of aggregation of analyses whose main use is the detection of trends in research objectives and results. They can also focus on methods, techniques, procedures, epistemological approaches, and even values (Levitt, 2020); knowing the perspective from which a researcher works enables the selection of findings to be questioned, if applicable.

When dealing with qualitative research, aggregation methods are called qualitative meta-analysis or metasynthesis (e.g., Paterson et al., 2001). And when they focus on analyzing the methods that have been used in the empirical studies reviewed, the adjective metamethod is used. One of the main objectives of metamethod studies is to document the standardization of uses in a research field; they are also useful to show the limitations of different methods (Levitt, 2020).

Metamethod studies are little known despite being of interest to our discipline given the remarkable growth of qualitative research on psychological topics (Delgado, 2013; Kidd, 2002; Levitt et al., 2018; Wertz, 2014). In the initial stages of a research program, it is key to have a detailed description of the phenomena under study. Otherwise, the observations required to generate and test substantive theories will be based on expert intuitions or theories implicit in ordinary language. Failure to address a phenomenon is not recognized as a methodological error (Laudan, 2000), even knowing that a carefully documented description could serve to detect limitations in dominant theories or discover the existence of unknown mechanisms (Rozin, 2009). This is the main reason why qualitative methods, in common use among psychologists (Delgado, 2013; Kidd, 2002; Madill & Gough, 2008; Wertz, 2014), are of interest to the scientist and not only, as one might think, to the practitioner.

Of course, the role of qualitative methods is not limited to the context of discovery: the classification of phenomena or their properties, in general, and the study of subjective experience, in particular, are other frequent uses in psychological practice and research (Delgado, 2010). There are guidelines for assessing the quality of these studies that call for reporting techniques, epistemological approaches, and researcher values if they are considered relevant to the interpretation of the results (Levitt, 2020; Levitt et al., 2018). However, it is still common to find articles that do not adequately report the procedure followed, limiting themselves to citing references from one or another approach or mentioning the commercial software program used to organize codes and generate figures.

It follows from the above that metamethod studies will be of particular relevance when they are aimed at analyzing research on new constructs related to subjective experience whose complexity requires a detailed description. This is the case of emotional regulation (ER), which refers to the attempt to influence our emotions, in the moment or the way in which they are experienced or expressed (McRae & Gross, 2020). There are several models, classifications, and terms associated with ER strategies (Braunstein et al., 2017; McRae et al., 2012; Nook et al., 2021). For example, in the process model (Gross, 1998), the most widespread, regulative strategies can be classified into five families: situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation.

Inadequate selection and implementation of regulative strategies (e.g., positively valuing substance use and abuse as an adaptive strategy) can lead to different forms of psychopathology. Similarly, errors in identifying a situation that requires emotional regulation and in monitoring the regulative process can lead to psychopathological manifestations (Sheppes et al., 2015). In the field of intervention, the improvement of the ability to regulate emotions is associated with the improvement of clinical symptoms of disorders such as depression, anxiety, substance use, eating disorders, and borderline personality disorder, so it is suggested that treatments aimed at improving ER could be contributing to the reduction of various psychological pathologies (Sloan et al., 2017).

From a quantitative perspective, it is already possible to find reviews of the most commonly used ER tests, ones that, in many cases, refer to various strategies without mentioning their theoretical provenance (Pérez-Sánchez et al., 2020a), simply asking about the frequency of use (McRae & Gross, 2020; Naragon-Gainey et al., 2017). Certain specific techniques have been particularly studied, such as suppression and reappraisal. Research carried out using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), the most widely used tests in the assessment of ER in adults, have shown that their scales have adequate psychometric properties (Pérez-Sánchez et al., 2020b). The same can be said of the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC) for the assessment of ER in children and adolescents (Pérez-Sánchez et al., 2022).

There is no doubt that psychometric tests allow us to quantify the relationship between variables and to make predictions regarding criteria of interest, as well as serving as support in decision-making (Muñiz & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019). However, given the complex nature of ER, its study has also been approached using qualitative methods. Hence, our objective has been to carry out the metamethod study of qualitative research on ER strategies since the beginning of the 21st century.

METHOD

Procedure and Materials

The search was conducted on July 27, 2021 in Web of Science and Scopus. The search strategy was as follows: ((("emotion regulation strategies" OR "situation selection" OR "situation modification" OR "attention deployment" OR "cognitive change" OR "response modulation" OR "reappraisal" OR "suppression")) AND (("qualitative analysis" OR "thematic analysis" OR "content analysis" OR "framework analysis" OR "grounded theory" OR "phenomenological analysis" OR "narrative analysis" OR "life history research" OR "conversation analysis" OR "discourse analysis" OR "ethnography"))). The following filters were applied: a) year of publication (within the last two decades), b) in the field of psychology and c) in English.

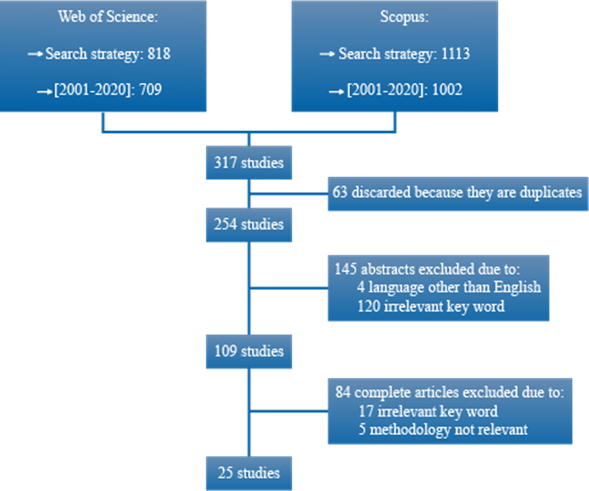

As shown in Figure 1, 317 studies were obtained based on the selection criteria. First, 63 duplicate titles were found. Then, of the 254 abstracts examined, 145 were discarded for the following reasons: 4 were published in a language other than English, 120 contained a keyword that did not correspond to those established in the search strategy (e.g., viral suppression), and in 21 the methodology was experimental, psychometric, or review/synthesis.

The remaining 109 studies were reviewed through the full text. Eighty-four articles were withdrawn because in 17 the keywords did not correspond to those established in the search plan (e.g., viral suppression or immune suppression, since they do not refer to the ER strategy known as suppression), in 5 the methodology was experimental, psychometric, or used a qualitative technique to name experimental variables, and in 62 the objectives did not match those of the metamethod study.

Finally, the 25 articles in which qualitative methodology was used to investigate ER strategies in different areas of psychology were selected. These articles are preceded by an asterisk in the list of bibliographic references.

Data Analysis

In the initial phase, the 254 abstracts obtained were registered in a database to determine whether they indeed referred to qualitative research on emotional regulation strategies, since search engines use keywords that do not always correspond to the contents of interest for the researchers' objectives. Based on the information obtained from the abstracts, 109 studies were selected and analyzed in full text version, in order to continue eliminating papers that were not relevant to our objective, as noted in the previous section.

For the 25 articles finally selected, information was recorded on: a) the year of publication, b) the number of participants, c) the qualitative analysis method, the guidelines and approach used, d) the data collection format, e) the methodological quality criteria, f) the area of study, g) the emotional regulation strategies, and h) the objective or focus of the study.

The data that could be categorized were coded by the authors in order to obtain the prevalence of the different methods, the scope of the study, etc.; discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. A metamethod study also requires analysis of the coherence between the techniques employed and the focus of the studies. Hence, the results of the analyses are included together with their discussion in a single section.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The search strategy was planned to include studies published in the 21st century. After the selection criteria were applied, it can be seen that most of the texts selected for analysis were from the second decade.

In terms of samples, most studies involved between 1 and 66 subjects. Two articles exceeded 100 (Speights et al., 2020; Stanley et al., 2012). And only in one study was the sample composed of posts rather than individuals (Stevens & Wood, 2019). Research participants were mostly female.

Regarding data collection, participants were recruited mainly in person (Table 1), at universities, hospitals, schools, sports venues, or at the participants' homes. Non-face-to-face collection was carried out through telephone contact, by e-mail, or on digital platforms. Thirdly, it can also be observed that data collection was almost always carried out verbally. There were 21 studies that employed interviews, conversations, or open-ended questions in an oral format. All the studies that used grounded theory or discourse analysis as a method of data analysis used this format. Three studies used the written format and one study collected information using the focus group method (which is not included as oral, to emphasize that it is a method of data collection that is distinct from the individual interview). The semi-structured interview is the method chosen by practically all researchers in this field.

It is worth noting that in 6 studies the saturation criterion—coming from the grounded theory approach and currently much discussed (Braun & Clarke, 2021a; 2021b)—was noted. Despite its appearance of objectivity, it depends on the analyst's impression that a point has been reached at which no more new themes or insights appear. Braun and Clarke (2021a) have pointed out that saturation has ended up serving, whether intentionally or not, as a rhetorical device to justify sample size; this is problematic for approaches such as the reflexive approach proposed by these authors, in which the themes or contents of the analysis are not considered to be objective realities waiting to be discovered by the researchers, but constructions in which values, categories, interests, etc., combine with the texts analyzed to yield themes and subthemes that are faithful to the object of study.

Regarding the methods of analysis, it was found that in 13 studies (Courvoisier et al., 2011; Gibbons & Groarke, 2018; Littlewood et al., 2018; Martinent et al., 2015; Normann & Hoff Esbjørn, 2020; Porter et al., 2016; Ringnes et al., 2017; Robbins & Vandree, 2009; Stevens & Wood, 2019; van der Horst et al., 2019; Van Doren et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2013; Willén, 2015), thematic analysis had been used (in 4 of these cases the qualitative study was part of a mixed design), in 8 it was qualitative content analysis (Drageset et al., 2010; Gumuchian et al., 2017; Haver et al., 2014; Kurki et al., 2015; Moscovitch et al., 2013; Stanley et al., 2012; Timraz et al., 2019; Williams, 2013), in 3 grounded theory (Lam et al., 2017; Morse et al., 2014; Speights et al., 2020), and in 1 discourse analysis (Ellis & Cromby, 2012). As reported in the articles, the indications used to carry out the thematic analysis were generally those proposed by Braun & Clarke (2006) in their pioneering article. For content analysis, the usual reference was Hsieh & Shannon (2005) . In the case of grounded theory, several references were used, mainly Strauss & Corbin (1998) and Glaser (1978) , representative of the first two branches into which the original procedure of this methodological approach divided. The reference provided in the articles to support discourse analysis is also a classic (Edwards & Potter, 1992). As for the software, 5 studies used some version of NVivo and only 2, Atlas.ti. The studies that reported the use of software for data analysis tended to employ a methodology based on qualitative content analysis. As we indicated in the introduction, it is still common to use references or mention a commercial software program to justify the method, without reflecting on the methodological integrity of the research. Have procedures been selected that are consistent with the phenomenon being studied as conceived based on the approach used (Levitt et al., 2018; Málaga & Delgado, 2020)? If not, the criterion of fidelity to the subject matter under study may not be met.

And continuing with methodological integrity, only a few studies indicated the approach used, complementing the information on the method of analysis, although not always adequately. For example, saying that a "Glaserian," "inductive," or "exploratory" approach was used does not add information on the ontological or epistemological orientation that its authors have followed in the research. In the first case, moreover, the method employed—grounded theory (together with the reference to Glaser, 1978)—includes the approach, unlike what happens in standard thematic analysis, which can be used as an "agnostic" method and would therefore require to be complemented by an approach appropriate to the objective if quality qualitative research is to be done. In this sense, the phenomenological approach was made explicit in 2 articles classified in the thematic analysis category (Gibbons & Groarke, 2018; Robbins & Vandree, 2009). Social constructionism was mentioned in a single case (Gumuchian, et al., 2017).

Table 1. Method of data analysis according to recruitment and data collection.

| Data analysis | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thematic analysis | Content analysis | Grounded theory | Discourse analysis | ||

| Recruitment | |||||

| Face-to-face | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Non-face-to-face | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Not provided | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Data collection | |||||

| Oral | 11 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 21 |

| Written | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Focus group | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Regarding the register of terms describing quality or methodological rigor, it is worth noting that 5 studies—mostly content analyses—mentioned the term trustworthiness. This is a general concept that must be accompanied by specific quality criteria. Table 2 shows that consensus among researchers was the procedure most frequently used to achieve methodological integrity. In 6 articles, this criterion was complemented by others, such as coherence with previous studies, member checking, reflexivity, audit trail, or grounding in the data by means of textual examples. Only 4 of the studies did not provide quality indicators. However, most of them referred to very basic issues such as consensus, which is not always considered relevant for a thematic or qualitative content analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021a; 2021b). For example, those who follow discursive approaches (in contrast to experiential ones; Reicher, 2000), find that criteria such as consensus or agreement among coders are heirs to a positivist philosophy that does not adequately reflect the epistemological orientation of a large part of today's researchers.

Table 2. Frequency of data analysis method according to quality control.

| Control | Data analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| quality | Thematic analysis | Content analysis | Grounded theory | Discourse analysis | Total |

| Consensus | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| Consensus + CO | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Consensus + CP | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Consensus + GD | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Consensus + CO + CP | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Consensus + RE + AU | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Not provided | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 13 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 25 |

Note: AU= audit; CO= consistency; CP= checking with participants; ED= groundedness in data; RE= reflexivity.

To analyze the coherence between the method of analysis used and the objective or focus of the research, the application setting (categorized as clinical/non-clinical), the emotional regulation strategies used, and the focus of the study were collected. Table 3 shows that the study of emotional regulation using qualitative methodology is common in the clinical setting. Of the 10 articles classified in the clinical setting, 4 referred to patients who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, 2 were linked to anxiety disorders, and the rest related to diverse topics (sexual abuse, borderline personality disorder, scleroderma, and spondylosis).

Table 3. Frequency of data analysis method according to area and emotional regulation strategies.

| Data analysis | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thematic analysis | Content analysis | Grounded theory | Discourse analysis | ||

| Setting | |||||

| Clinic | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| Non-clinical | 9 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| Strategies | |||||

| ER | 9 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 16 |

| Coping | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Suppression | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Note: ER = Emotional regulation

The remaining 15 studies were classified as having a nonclinical setting because their objectives were focused on the study of emotional regulation in research in academic areas (basic, social, and educational) or in applications in various fields (e.g., forensic). The emotional regulation strategies considered also varied. On the one hand, general groupings of emotional regulation strategies stand out (such as the families proposed in the process model; Gross, 1998) and, on the other hand, more specific techniques such as suppression, avoidance, reappraisal, social support, positive thinking, or awareness. Seven studies referred to coping strategies that also included suppression, avoidance, reappraisal, and support-seeking, together with distraction, acceptance, or relaxation techniques. Finally, only 2 studies focused on a single emotional regulation strategy: suppression. From a theoretical point of view, those known as coping strategies are usually studied in relation to stress management rather than emotion management. However, it is observed that the specific strategies categorized as coping strategies are also ER strategies and this is true in both quantitative and qualitative research.

Fidelity to the object of study, assessed by the coherence between the approaches/methods and the objective or focus of the studies, was satisfactory. In general, content analyses, which tend to be epistemologically more conservative, set out to describe, examine, or explore ER strategies in different settings. Only one of these studies, which mentioned the social constructionist approach (Gumuchian, et al., 2017), aimed to understand coping strategies, an objective that seems more in line with a phenomenological approach. The only discourse analysis focused on expressive styles associated with emotional inhibition (Ellis & Cromby, 2012). In the three investigations that employed the grounded theory methodology, there was also method-objective consistency, as they focused on seeking possible explanations—factors, influences, etc.—well-grounded in the data. The focus of the thematic analyses was very similar to that of the qualitative content analyses. Of note is the fidelity to the object of study shown by Robbins and Vandree's (2009) phenomenological approach to thematic analysis, focused on understanding the experience of suppressing laughter. The combination of thematic analysis and phenomenological approach is none other than the descriptive phenomenological method, whose role in scientific psychology, and more specifically in the research on emotional experience, is significant (Delgado, 2010; 2013; Wertz, 2014).

In conclusion, the meta-method study of qualitative research on ER strategies reflects the growing interest in the study of this psychological construct in recent years. The semi-structured interview has been the usual procedure for data collection; thematic analysis, the most common method. In general, the choice of the method of analysis has been consistent with the objective of the study. In future research, the choice of qualitative methods should be justified according to the approach adopted. It is also recommended to employ—and describe—quality control methods consistent with objectives and approaches. Finally, with regard to ER strategies, it is hoped that future studies will contribute to improving the description and classification of regulatory techniques in different contexts.

texto en

texto en