Mental Disorders and Criminal Responsibility in the Spanish Supreme Court

Spanish doctrine establishes that a person may be declared criminally liable for the actions being tried if, at the time of committing the criminal offense, they had full capacity to understand the unlawfulness of the act (cognitive capacity) as well as the capacity to direct their action in accordance with this understanding (volitional capacity) (Molina et al., 2009). This capacity to act in accordance with the administrative sanctioning law is what is known as imputability (Barrios, 2015).

There are three levels of mental circumstances that can change criminal responsibility (CR) in Spanish law (Pérez-Sauquillo, 2018). At the full degree of imputability, the understanding and will are not distorted or subject to mental alterations or illnesses. At the level of partial CR or semi-imputability, the person suffers or has suffered a mental alteration or illness that interferes with his or her higher mental functions, without completely annulling them. At the level of non-imputability, the cognitive and/or volitional capacity is annulled, and there is a perfect causal correspondence between the disorder and the crime (Cano-Lozano, 2006).

The CR sentence requires that the mental state be reconstructed retrospectively at the time of the crime (Mandarelli et al., 2019), assessing three crucial aspects in the determining of imputability: establishing the clinical diagnosis, objectifying the degree of extent of mental dysfunctions, analyzing the psychological effect produced by the disorder on cognition and/or volition, and establishing a causal relationship between the psychological alteration and the crime in question (Dujo et al., 2016).

Despite the consideration that the legal system gives to mental disorders, there is a high prevalence of psychiatric pathology in the prison population (Esbec & Echeburúa, 2016). Research shows that, upon admission to prison, the need for treatment in the psychiatric area is high, since most inmates present anxious and depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits (Casares-López et al., 2012). Several studies on the prevalence of mental disorders in Penitentiary Institutions in Spain (López et al., 2016; Secretaría General de Instituciones Penitenciarias [General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions], 2016; Vicens et al., 2011) have indicated that around 85% of inmates had a history of having suffered a mental health problem throughout their lives, the most prevalent ones being substance use disorder, affective disorders, and psychotic disorders.

Contrary to the existing interest, there are few studies that analyze the legal treatment of mental disorders in Spain; the studies are old and focused on a specific population or on specific mental disorders. Cano-Lozano et al. (2008) reviewed Supreme Court judgments between 1995 and 2006 that requested the modification of CR on psychological grounds, finding that complete and incomplete exemptions accounted for 35% of the approved legal status instances, while mitigating circumstances accounted for 65%. Pintado (2019) reviewed the sentences passed in the Basque Country between 2010 and 2018 and observed that CR was exempted on only 9.6% of occasions, with schizophrenia being the alteration with the greatest power in the modification of liability. Lorenzo et al. (2016), Mohíno et al. (2011), and Penado and González (2015) did the same for personality disorders, concluding that the reduction in CR of this diagnostic group is minor, although more accentuated if there is comorbidity. Beizama et al. (2016) studied this with respect to intellectual disability, noting that the presence of this disorder in Spanish case law is likely to be a modifying circumstance of CR in most cases.

The present study arises with the purpose of illuminating the treatment that mental disorders have in the current penal context, in order to help professionals of the judicial system to identify the influence of mental disorders in determining imputability, as well as to make appropriate decisions regarding the measures to be applied. Thus, the main contribution of our study is the joint analysis of the different psychological disorders in the current penal context, throughout the national territory.

The objective is to understand the repercussion that mental disorders have in determining imputability in current Spanish jurisprudence. The specific objectives are, firstly, to describe the criminal and psychological profile of the individuals involved in these situations, including sex, background, types of offenses, the psychological alteration they suffer, and their comorbidity. Secondly, the aim is to find out the legal characteristics of the appeal in terms of CR, the legal statuses that are pleaded and approved, the changes of criteria with respect to the Sentencing Court, and the type of penalties or measures of deprivation of liberty conferred. The final intention is to establish the psychological-legal interdependence, studying the relationship between psychological alterations and CR, exonerating, and mitigating legal statuses.

Method

An empirical, descriptive, and retrospective study was conducted by reviewing the sentences, according to the classification proposed by Montero and León (2007).

Material and Procedure

The judgments were collected through the Aranzadi digital Legal Sciences database (Thomson Reuters). Those corresponding to the Criminal Chamber of the Spanish Supreme Court during the period between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2019 were selected, opting for the judgments of the Supreme Court because it is the highest ruling body and the most authoritative source on this subject. The terms used as markers in the search were those associated with the psychological constructs contained in the Penal Code (1995) with respect to legal statuses (see Table 1).

Table 1. Terminology markers.

| Article of the Penal Code | Terminology marker |

|---|---|

| 20.1 | Mental anomaly |

| Mental alteration | |

| Transient mental disorder | |

| Mental derangement * | |

| 20.2 | Full intoxication |

| Withdrawal syndrome | |

| 20.3 | Alteration in perception |

| 20.6 | Insurmountable fear |

| 21.2 | Serious addiction |

| 21.3 | Fit of rage |

| Blindness, | |

| Another passionate condition of similar entity | |

| 21.7 | Mitigating circumstance by analogy |

Note: * The term “mental derangement” was included due to its high representation in the legal field, despite it being an obsolete construct.

A total of 449 sentences were obtained in the search phase, of which 89 were discarded in the screening phase, according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The defendants in the criminal proceedings who were found to be responsible for the crime or non-imputable material perpetrators were extracted from the sentences. The accused also met the condition of requesting or having requested any of the exonerating and/or mitigating circumstances for psychological reasons set out in the Penal Code (1995), regardless of the time of the process at which the request was made, the only condition being that it was mentioned in any of the sections of the Supreme Court sentence. All individuals were taken into account, regardless of who filed the appeal and the reasons for requesting it. Judgments in which, despite containing the terminological markers, no modification of responsibility on psychological grounds was requested or applied, those that declared a mistrial or acquitted the defendant on non-psychological grounds, and those judgments that did not contain all the relevant parts were excluded. It was decided to exclude those judgments declaring a mistrial or acquitting the defendant on non-psychological grounds, since these judgments do not establish the existence of any crime, and therefore the defendant could not be responsible for it.

In the coding phase, data from 360 sentences were entered, and a total sample of 501 defendants was obtained. Information was extracted from 15 variables. In some sentences it was not possible to record all the data because it was not explicitly stated. Appendix A defines the set of variables recorded, as well as their different categories.

The coding of the sentences was performed by two independent judges. Each of the judges coded 45% of the total number of sentences. The remaining 10% were coded independently by the two judges to ensure the completeness and concurrence of the data collected. Once the coding was completed, the concordance of the data obtained in these sentences was analyzed, and it was observed that the two judges involved coded 100% of the data in the same way.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used, specifically frequency and percentage analysis. The frequency distribution was compared with the chi-square test, using the binomial test when the variable was dichotomous. The normality of the data in the quantitative variables was contrasted with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Contingency tables were used to study the association between nominal variables. All analyses were contrasted at a significance level α < .05. The analyses were performed with the SPSS 25.0 program.

Results

Psychological-Delinquent Profile

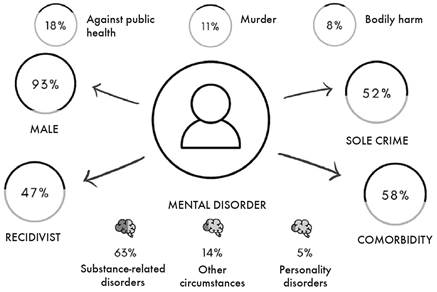

Figure 1 represents the psychological-criminal profile of the defendants. Of the 501 individuals charged, 464 (92.6%) were male. Information regarding criminal history was recorded in 368 cases, of which 174 (47.3%) had a criminal record. Regarding the type of crime, 260 (51.9%) were tried for the committing of a single offense and the remaining 241 (48.1%) were tried for two or more offenses. The crime against public health was the most frequent (18.2%), followed by murder (10.5%), bodily harm (7.6%), and robbery (7.4%).

Psychological disturbance was defined based on the diagnostic criteria for mental disorders of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (2013). In addition, other circumstances that, whilst not mental disorders, could have altered the psychological state of the individual were included (for more information, see Appendix A). A total of 57.5% of the defendants presented comorbidity of pathologies. For this reason, the total number of disorders recorded (783) is higher than the number of individuals prosecuted (501). The most frequently observed psychopathological categories, without differentiating between main disorder and comorbid disorder, were those related to substances and addictive disorders (62.8%), specifically the consumption of other substances or unknown substances (22.1%), consumption of stimulants (12.6%), and alcohol intoxication (6.1%). This was followed, far behind, by the category "other circumstances" (13.7%), the most frequent being arguments or fights (4.5%) and relationship problems (4.0%). The third most frequent psychopathological group was personality disorders (5.1%), specifically unspecified personality disorder (2.4%) and paranoid and antisocial personality disorders, in equal proportion (0.6%).

Legal Results

The CR of the defendants was reduced or annulled on 190 (37.9%) occasions, regardless of the instance in which it was resolved. Of the sentences that included a reduction or annulment of CR, exonerating legal status was granted in 10 (5.3%) cases, semi-exonerating status in 26 (13.7%) cases, and mitigating circumstances were deemed in 154 (81.0%) cases. In 202 (40.3%) cases, more than one legal status was pleaded; therefore, the total number of pleaded legal status instances counted (761) was higher than the number of individuals charged (501). On three occasions, two legal statuses were approved for the same defendant; therefore, the total number of approved legal status instances counted (193) was higher than the number of sentences in which CR was modified (190).

The most frequently invoked legal status was the mitigating circumstance of serious addiction, with an outstanding percentage of 29.2%. This was followed far behind by the mitigating circumstance of fit of rage, blindness, or another passional condition of similar entity (8.7%) and incomplete exemption in relation to mental anomaly or alteration (8.5%). The legal status most frequently approved was also the mitigating circumstance of serious addiction (34.7%), followed by the analogous mitigating circumstance in relation to serious addiction (23.3%), and the analogous mitigating circumstance in relation to mental anomaly or alteration (8.3%).

Of the total number of defendants, 393 (78.4%) filed an appeal before the Supreme Court requesting a review of CR on psychological grounds. The rest did not file an appeal, or they filed an appeal on other grounds. Of the 190 cases in which mitigating and exonerating legal statuses were approved, 167 (87.9%) were granted in previous instances, and 23 (12.1%) when the appeal was made in cassation to the Supreme Court. In other words, of the 393 cases in which an appeal was made to the Supreme Court requesting modification of CR on psychological grounds, only 23 (5.8%) involved a change of criterion with respect to the ruling of the sentencing court.

Forensic Results

Table 2 shows the relationship between psychological disorders and the approved exonerating and mitigating legal statuses. The nosological category of substance-related disorders and addictive disorders has the highest frequency of estimated legal status instances (64.2%). It is followed by other circumstances (10.4%), schizophrenia spectrum (8.8%), and personality disorders (7.3%).

Table 2. Approved legal status according to the main psychological disorder.

| Main psychological disorder |

Approved legal status Frequency (%) |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20.1 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 21.7 | ||

| Substance-related and addictive disorders | - |

5 (2.6) |

62 (32.1) |

1 (0.5) |

56 (29.0) |

124 (64.2) |

| Other circumstances | - |

5 (2.6) |

1 (0.5) |

4 (2.1) |

10 (5.2) |

20 (10.4) |

| Spectrum of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders |

7 (3.6) |

4 (2.1) |

1 (0.5) |

- |

5 (2.6) |

17 (8.8) |

| Personality disorders | - |

6 (3.1) |

2 (1.0) |

1 (0.5) |

5 (2.6) |

14 (7.3) |

| Neurodevelopmental disorder | - |

2 (1.0) |

1 (0.5) |

- |

1 (0.5) |

4 (2.1) |

| Trauma-related disorders and stress factors | - |

1 (0.5) |

- |

1 (0.5) |

- |

2 (1.0) |

| Neurocognitive disorders |

2 (1.0) |

- | - | - |

1 (0.5) |

3 (1.6) |

| No record | - |

3 (1.6) |

- | - | - |

3 (1.6) |

| Bipolar disorder and related disorders |

1 (0.5) |

- | - | - |

1 (0.5) |

2 (1.0) |

| Anxiety disorder | - | - | - | - |

1 (0.5) |

1 (0.5) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders | - | - | - | - |

1 (0.5) |

1 (0.5) |

| Somatic symptom disorders and related disorders | - | - | - | - |

1 (0.5) |

1 (0.5) |

| Paraphilic disorders | - | - | - | - |

1 (0.5) |

1 (0.5) |

| Total |

10 (5,2) |

26 (13,6) |

67 (34,7) |

7 (3,6) |

83 (43,0) |

193 (100,0) |

When analyzing the mental disorders suffered by the defendants according to the modification of CR (complete exemption, incomplete exemption, and attenuation, respectively), it was observed that in the 10 cases in which they were completely exempted from responsibility, up to 70.0% were diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and other psychotic disorders, and 20.0% with neurocognitive disorder. In the 26 cases that were incompletely exonerated, personality disorders were the most represented (23.1%), followed by substance-related disorders and other circumstances in equal proportion (19.2%). In the 154 cases in which responsibility was mitigated, 77.3% suffered from substance-related and addictive disorders. This was followed by other circumstances (8.4%) and personality disorders (5.2%).

In 12 cases, security measures involving deprivation of liberty were applied, of which 11 individuals were sent to a psychiatric center, the majority being persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (58.3%). In only one case was a decision made to place them in a rehabilitation center.

Discussion

The analysis of Supreme Court jurisprudence shows that the profile of offenders with mental disorders is mostly male and that a high proportion are repeat offenders. The most frequent types of crime are crimes against public health (18.2%), murder (10.5%), and bodily harm (7.6%). The most prevalent mental disorders in the sample were, by far, substance-related disorders and addictive disorders (64.1%), followed by the group of circumstances that, whilst not actually being mental disorders, altered the mental state of the accused (15.8%), and personality disorders (5.4%); up to 57.1% of cases had comorbidity of pathologies. In the study conducted by Cano-Lozano et al. (2008) between 1995 and 2006, an analogous psychological-delinquent profile was obtained, coinciding in the typologies, and varying very slightly in frequency.

The Supreme Court admitted the review of 393 cases on psychological grounds, changing its criteria with respect to the Sentencing Court in only 23 of them (5.8%). From these results it can be deduced that the propensity of the Supreme Court is to maintain the criteria of previous rulings. Identical conclusions were reached by Mohíno et al. (2011) in their study of Spanish case law.

The CR of defendants was modified for psychological reasons in 190 (37.9%) cases; complete and incomplete exemptions represent 19.0% and mitigating factors 81.0%. Cano-Lozano et al. (2008) found a distribution of complete and incomplete exemptions of 35% and mitigating circumstances of 65%. It seems that the trend has been to increase the application of mitigating factors to the detriment of exonerating factors.

In the 10 cases that were completely exempted from CR, 70.0% were diagnosed as being on the schizophrenia spectrum. In the 26 cases that were incompletely exempted, personality disorders were the most represented (23.1%), followed by addictive disorders and other circumstances in equal proportion (19.2%). In the 154 cases in which liability was mitigated, up to 77.3% suffered from substance-related disorders and addictive disorders.

The results indicate that schizophrenia spectrum disorders show the greatest power in the modification of CR. A total of 28.0% of the cases were found to be completely exempt from liability and 16.0% were incompletely exempt. The most frequently approved legal status was complete exemption due to mental anomaly or alteration. The review of sentences from the Basque Country carried out by Pintado (2019) shows a complete exemption of 32% and an incomplete exemption of 46% among individuals with schizophrenia. Mandarelli et al. (2019) concluded that non-imputable defendants were more likely to be affected by schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar spectrum disorders. Similarly, Esbec and Echeburúa's (2016) theoretical review indicates that the natural tendency regarding the imputability of schizophrenia is toward full exemption.

With regard to personality disorders, CR was modified in more than half of the cases: 29.6% mitigating circumstances and 22.2% incomplete exemptions. The legal status approved most frequently was the analogous mitigating circumstance with respect to mental anomaly or alteration. Lorenzo et al. (2016) studied the jurisprudential treatment of personality disorders, reaching the conclusion that the Supreme Court, as a general rule, understands that these disorders are criminally assessed as an analogical mitigating circumstance, that simple maladaptive personality traits do not affect imputability, and that incomplete exemption is exceptional and reserved for very serious cases or those associated with drug addiction or other mental disorders. Mohíno et al. (2011) agree in their conclusions, noting that, in their sample, CR with personality disorders varies in relation to the type of disorder, its severity, the comorbidity, the level of influence on volitional capacity, the type of criminal behavior, and the specific circumstances. With these data, it can be concluded that personality disorders have slight power in the modification of CR, which can be emphasized by multiple factors, and that the jurisprudential tendency is to consider it as an analogical mitigating factor.

Substance-related and addictive disorders are the most prevalent disorder and, although in more than half of the cases individuals were considered fully responsible for their acts, this is the psychopathological group with the highest frequency of mitigating circumstances approved. The legal status most granted is the mitigating circumstance of serious addiction. Muñoz (2014) studied the jurisprudential treatment of drug addicts, finding that most of the problems that arise in criminal-legal practice are derived from this psychopathological group. For a long time, a direct relationship has been established between crime and substance abuse, with consumption functioning as a trigger for multiple crimes in the majority of people with mental disorders (Esbec & Echeburúa, 2014). In the present study substance users represent 64.1% of the sample, in that of Cano-Lozano et al. (2008) they comprise 60.8%, and in the study of Pintado (2019), 72.6%. These data are confirmation of the huge influence that drug dependence has on delinquency. Most addicts are criminally responsible for the unlawful behaviors committed (61.4%), but addiction can in some cases undermine the person's ability to control his or her behavior. When this is proven, responsibility is either mitigated (37.1%) or incompletely exempted (1.6%).

According to the statistics of the Consejo General del Poder Judicial [General Council of the Judiciary] (2022), between January 2015 and December 2019, the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court resolved a total of 4,133 sentences; 360 (8.7%) requested mitigating or exonerating circumstances for psychological reasons. In that period, up to 501 defendants requested modification of CR due to psychological conditions. It is urgent to have forensic psychology professionals to assist the justice system, since psychological alterations are, as we have seen, undeniably present in the legal context.

The data provided in our work confirm the importance of the expert evidence and lay the foundations for the need to develop specific assessment instruments and protocols that, from a dimensional perspective, not only allow the diagnosis of the mental disorder, but also make it possible to accurately assess the existence of a causal relationship between the mental disorder and the crime committed. These evaluation protocols should be particularly exhaustive with regard to addictive disorders, given that they represent almost two thirds (62.8%) of the cases.

As for the adoption of therapeutic measures, only in 11 cases was internment in a psychiatric center imposed, and in one case in a rehabilitation center. It is noteworthy that, despite recognizing the influence of mental disorders on the mental state of the accused on 190 occasions, no alternative measures have been adopted to fulfill the function of rehabilitation and social reintegration established by law. This problem was already detected by Martínez et al. (2001), since of the 200 Supreme Court sentences these authors reviewed between 1992 and 1998, except in one case, the measure was reduced to the application of a lesser penalty. Almost 20 years later, the trend remains the same and the adoption of therapeutic measures is undeniably the exception rather than the rule.

These alarming data highlight the need to strengthen the adoption of therapeutic measures. Specialized psychological treatment not only has an impact on the well-being of individuals, but it also has a positive impact on society: the risk of recidivism would be significantly reduced.

It is also essential to reinforce therapeutic treatment in prisons. The high prevalence of mental pathology (around 85%), mainly addictive disorders, requires specialized attention. Considering the figures obtained in our study, it is inevitable to reflect on the huge importance of treatment teams in prisons.

CR does not depend exclusively on the clinical diagnosis; it must be causally related to the committing of the crime, and it must have altered the cognitive and volitional capacities of the perpetrator. It is up to the expert to collect and interpret the data and to the judge to evaluate the veracity of the conflicting hypotheses based on the interpretation of these data (Subijana & Echaburúa, 2022). Therefore, the greater the knowledge that judges have regarding mental disorders and their implications the more closely judicial rulings will be adjusted to the characteristics of these individuals. Our work highlights the need for adequate coordination and cooperation of all the agents involved in the judicial process.

The idea of this study was born out of this need, with a desire to understand the current jurisprudential treatment of mental disorders and, thus, to optimize our work as assistants of justice. Thus, an updated national overview has been provided, with a time frame of five years, which allows a comparison between the different psychopathological groups and their prevalence in the criminal field. In addition, it broadens the knowledge regarding the penalties and security measures adopted.

As limitations, it should be noted that the sentences reviewed showed a conglomeration of terms that reflects the multiplicity of existing approaches in the clinic, making it difficult to structure and study them. In addition, the lack of terminological unity prevented an exhaustive search of the sentences, leaving out of the study all those that did not fit the generic terms used. Furthermore, the selection of the case law of the Supreme Court carries a certain bias, since it is less common for minor offenses to reach higher courts. Finally, it should be noted that the retrospective study of the sentences limited the information available, and we were unable to include information on the evaluation of the psychological alteration.

The determination of the CR of persons with mental disorders is essential for judicial decisions and measures to be adjusted to the needs of these individuals. Given the importance of the expert's work in this context, we propose as a future line of research the detailed study of the functions of the expert in the justice system, as well as their influence on the ruling of imputability. It would be of interest to know how the ruling changes depending on the existence of psychological expertise, the number of experts involved, the party requesting it, and their intervention in the oral trial. To conclude we highlight the crucial need for psychology and law to interact in the search for the best justice.