“The word “entrepreneur” has been glamourized by today's media. When you hear the word “entrepreneur,” you are often shown an image of successful people with profitable, rapidly growing businesses and a glamorous lifestyle. Unfortunately, this representation of entrepreneurship reflects a minute fraction of entrepreneurs. The reality is that 8 out of 10 startups fail. The reality is that starting and running a business is psychologically and mentally distressing. It is years of dedication and relentless hard.”

Mr. Ahmed Osman

Past Chair of the International Council for Small Business

More than five years ago, in this same journal, Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa (2016)formulated the path to follow in the research of entrepreneurial personality. In this period, and with their help, an attempt has been made to advance in this field of knowledge. The same logic will be followed. Here we will present the point where the research on the entrepreneurial personality is at present and the possible paths that can be followed in the near future.

The Entrepreneur

Entrepreneurship has been a hot topicin the last few decades (Chell, 2008; Gielnik et al., 2021). The source of innovation, employment, and productivity it brings to a country makes it a formidable engine for growth in any economy (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor [GEM], 2020, 2021; Van Praag & Versloot, 2007). Moreover, entrepreneurship is essential in organizational psychology, since organizations, companies, and businesses only exist because of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship (Baum et al., 2007). One of the main motives guiding the study of entrepreneurship is the aim to analyze why some people, and not others, start a business. Furthermore, there is the purpose of analyzing why, among the people who are entrepreneurs, some succeed while others end up having to close their businesses.

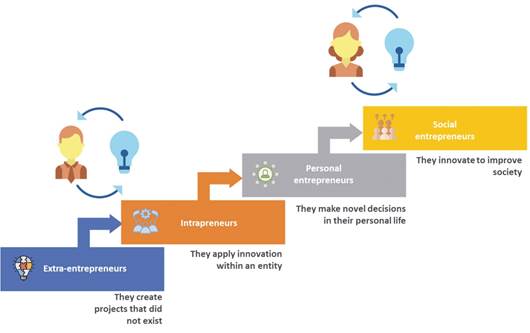

One of the explanations guiding this reasoning is the more personal aspect of the individual. Suárez-Álvarez (2015)defines entrepreneurship as amultidimensional process that determines personal development oriented towards the proposal, resolution, and maintenance of new projects, whether these are of an economic, personal, or social nature. Thus, the entrepreneurial person can develop in multiple contexts (Figure 1; Muñiz et al., 2019). It is possible to differentiate, therefore, the person whose goal is the development of new external projects linked to business creation (extra-entrepreneur; Rauch & Frese, 2007b), from the person who innovates within an organization, improving projects that are already underway (intrapreneur; Lumpkin, 2007; Mumford et al., 2021). The person who manages difficult situations related to stressors, unemployment, or changes at work must be distinguished (personal entrepreneur; Frese & Fay, 2001) from the person who undertakes for social purposes (social entrepreneur; Dees et al., 2001). Similarly, entrepreneurs should also be differentiated according to the stage of business they are in, the type of business (family, agricultural, technological, service sector, and franchising) and according to their pre-entrepreneurship situation, such as unemployed people or immigrants (see Salmony & Kanbach, 2021).

The Psychological Approach to the Study of Entrepreneurship

Throughout the 21st century, there have been four main approaches to the study of entrepreneurial activity: economic, sociological, biological, and psychological. Within the psychological approach, which is the one that concerns us here, there have been variations on its influence on entrepreneurial activity. In the 1980s, the psychology of entrepreneurship or entrepreneurial psychology had not found its place in the literature. In fact, Gartner (1989)in his famous article "Who is an entrepreneur?" Is the wrong question, focuses on the rejection of the trait approach (and everything psychological), stating that no entrepreneur can be defined on the basis of his or her personal characteristics. The main reason is that during those years this approach had made little progress in the explanation and prediction of entrepreneurial performance (Wortman, 1987). As stated by Baum et al. (2007), despite the belief that personal characteristics are important for the creation and success of businesses, the psychology of entrepreneurship had not been widely studied. It is from the 21st century onwards that different perspectives within the psychological approach begin to gain recognitionwhen explaining the determinants that lead people to entrepreneurship and business success. Since then, it has begun to be demonstrated that entrepreneurship is fundamentally personal (Baum et al., 2007, p. 1), since it is an effort that depends largely on the actions of the entrepreneurial person (Frese, 2009). So much so that the GEM Spain report (2020, p. 29), in its framework of entrepreneurial activity, establishes psychological attributes as one of the central axes of entrepreneurship. Therefore, and as concluded by Cardon et al. (2021)in their recent chapter entitled The Psychology of Entrepreneurship: Looking 10 years back and 10 years ahead, "Gartner challenged us all to think beyond who an entrepreneur is in order to understand a more complex phenomenon of what entrepreneurs do and why, how they act, think, and feel" (Cardon et al., 2021, p. 566).

One of the essential aspects of the psychological approach in the entrepreneurial context is the success of training in different psychological aspects related to entrepreneurship, known as entrepreneurship training and transfer(ETT; Weers & Gielnik, 2021). ETT has responded to one of the major debates among professionals: whether the entrepreneur is born or made (Gartner, 1989; Ramoglou et al., 2020; Schoon & Duckworth, 2012; Walter & Heinrichs, 2015). Evidence shows that ETT can be effective in both the short and long run (Blume et al., 2010; Martin et al., 2013; Ubfal et al., 2019; Walter & Block, 2016). However, and as is the case in multiple disciplines, results vary widely depending on the study and methodology applied (Martin et al., 2013), and insufficient evidence has been provided on how and why ETT is effective (Weers & Gielnik, 2021).

It could be stated that the psychological approach is integrated in the combination of three perspectives: cognitive (Baker & Powell, 2021), affective (Huang et al., 2021), and personality. The present work will focus on the latter.

The Entrepreneurial Personality Perspective

This perspective emphasizes the personality traits of entrepreneurs, which help to make some individuals more likely than others to start a business and to be successful in it (Rauch & Frese, 2007a, 2007b). Research on entrepreneurial personality has been increasing exponentially (Frese & Gielnik, 2014; Rauch & Gielnik, 2021). In fact, of all the meta-analytic reviews conducted on the psychology of entrepreneurship, those on entrepreneurial personality (Rauch & Frese, 2007b; Stewart & Roth, 2001; Zhao et al., 2010; Zhao & Seibert, 2006) are the most cited in the literature (see Rauch & Gielnik, 2021, pp. 489-491). The rise of this perspective has been spurred by a consensus on a general model of personality (Big Five model; Costa & McCrae, 1992) and by the use of meta-analysis as a technique for aggregating and generalizing the results of many individual studies (Brandstätter, 2011). Thus, different positions have tried to explain, to a greater or lesser extent, which aspects of personality lead a person to start a business. One idea is that the person who decides to become an entrepreneur is shown to have certain personality traits that lead him or her to "self-select" for an entrepreneurial career (Walter & Heinrichs, 2015).

Within the entrepreneurial personality, there is a debate, which continues today, between those who advocate assessing entrepreneurial personality through broad personality traits (such as the Big Five model) and those who advocate assessing personality through more specific traits. Personality traits can be measured with different degrees of conceptual breadth (Soto & John, 2017). A broad character trait allows us to summarize a large amount of behavioral information and predict a wide variety of relevant criteria (having the advantage of breadth). A narrowly measured trait, on the other hand, has the advantage of fidelity, i.e., it accurately expresses a specific behavioral description and can predict criteria closely linked to that description (John et al., 2008). The fact that different breadths in personality traits have advantages and disadvantages is known as the bandwidth-fidelity tradeoff(John et al., 1991).

Within the psychology of entrepreneurship, researchers have focused on general personality frameworks (breadth), such as the Big Five model (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Goldberg et al., 2006; McCrae & John, 1992). The Big Five model captures individual differences in the way people feel, think, and behave along five broad dimensions: openness (broadminded vs. closed minded), conscientiousness (well-organized vs. careless), extraversion (sociable vs. reserved), agreeableness (compassionate vs. competitive), and neuroticism (emotionally unstable vs. stable). Supporting the assumption that psychological traits play an important role in the entrepreneurial process, research shows that the Big Five model successfully predicts both business creation and entrepreneurial success (Obschonka, Duckworth et al., 2012; Obschonka, Silbereisen et al., 2012; Shane et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010; Zhao & Seibert, 2006). Thus, this approach continues to be used today in research on entrepreneurial personality (Antoncic et al., 2015; Dai et al., 2019; Fichter et al., 2020; Hussein & Aziz, 2017; López-Núñez et al., 2020; Sahinidis et al., 2020).

However, other researchers consider that trying to encompass many behaviors (breadth) in only five broad characteristics may become too reductionist (Almeida et al., 2014; Leutner et al., 2014; Muñiz et al., 2014). Specific entrepreneurial personality traits provide a more accurate description (fidelity) of how entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs differ on specific behavioral dimensions, allowing them to predict outcomes more accurately (Baum et al., 2007; Cuesta et al., 2018; Paunonen & Ashton, 2001; Rauch & Frese, 2007a; Suárez-Álvarez et al., 2014). For example, a meta-analysis by Rauch and Frese (2007b)showed that personality traits that were more closely related to the task of running a business were stronger predictors of business creation (r= 0.247) than general personality traits such as the Big Five (r= 0.124). Recent research has shown that specific personality traits offer, relative to the Big Five, incremental validity for predicting both business creation and entrepreneurial success (Leutner et al., 2014; Postigo, Cuesta, García-Cueto et al., 2021). Another advantage of taking into account specific traits is that they are more malleable than general, Big Five-type traits. As they are more specific traits (and, therefore, more specific behaviors), it is easier to intervene on them and try to enhance them. Personality change is not an oxymoron, as a person can change over time depending on life experiences (Blackie et al., 2014). In fact, recent longitudinal studies have shown that moving up in a company and even moving from employed to self-employed leads to changes in personality test scores (Li, Li et al., 2021; Li, Feng et al., 2021).

Entrepreneurial Personality Models

There are different theoretical models that have attempted to define the personality of an entrepreneur. Because the personality of the entrepreneur is a relatively new topic in the 21st century, there is considerable diversity in the personality traits of the different theoretical models. There are, however, certain personality traits that are essential to most theorists (Frese & Gielnik, 2014; Rauch & Gielnik, 2021). A summary of the entrepreneurial personality models with the definitions provided by their authors can be found below (Table 1).

Table 1. Entrepreneurial Personality Models.

| Model | Dimensions | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Personality Model (Rauch & Frese, 2007a) | Achievement motivation | A preference for challenges rather than routines, taking personal responsibility for their performance, and seeking feedback on their performance as well as new ways to improve it (Rauch & Frese, 2007a). |

| Risk taking | The probability or propensity of a person to take risks (Rauch & Frese, 2007a). | |

| Innovation | The inclination and interest to search for new forms of action (Patchen, 1965). | |

| Autonomy | The preference to be in control, to avoid restrictions and rules by organizations and, therefore, to choose entrepreneurial work (Brandstätter, 1997). | |

| Locus of control | Implies that one has the belief of controlling one's destiny and one's future (Rotter, 1966). | |

| Self-efficacy | The belief of being able to perform a certain action effectively (Rauch & Frese, 2007a). | |

| Cambridge University Psychometric Center Model - Barclays | Risk appetite | The degree to which one is willing to take risks and miss experiences. |

| Locus of control | The extent to which an individual believes that his or her actions and behaviors determine the outcomes of external events. | |

| Achievement motivation | The level at which a person needs success for self-motivation and strives for excellence and recognition. | |

| Self-efficacy | The way in which people perceive their capability as the way in which they perform novel and difficult tasks and overcome adversity. | |

| Autonomy as an attitude | Attitudes toward the degree to which others need autonomy. | |

| Autonomy as a necessity | The degree to which a person needs independence and freedom to make decisions freely, especially regarding the expectations of his or her workplace. | |

| Initiative | The level of how a person behaves at work. | |

| Innovation | The level at which a person seeks novelty and complexity, being willing to embrace and drive change. | |

| Entrepreneurial and Intrapreneurial Attitudes Model (Jain et al., 2015). | Achievement orientation | A driving force for successful entrepreneurship. |

| Risk taking | An individual's ability to take calculated risks and meet achievable challenges. | |

| Internal locus of control | The personal belief about the influence a person has on outcomes through his or her ability (Rotter, 1966). | |

| Innovation | The tendency to engage and support new ideas, creative processes, and experimentation that can lead to new products, services, and technological processes (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). | |

| Proactivity | An opportunity-seeking and forward-looking perspective that involves new products or services ahead of competitors and acting in anticipation of future demand to create change (Lumpkin & Dess, 2001). | |

| Market orientation | The generation of market intelligence concerning future customer needs, promoting horizontal and vertical intelligence within the organization (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). | |

| Measuring Entrepreneurial Talent(META; Ahmetoglu & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2013). | Business creativity | The ability to generate innovative business ideas. |

| Opportunism | The tendency to detect new business opportunities. | |

| Proactivity | The tendency to be proactive about projects. | |

| Vision | The ability to look at the business globally and create business progress. | |

| The Entrepreneurial Personality System(EPS; Obschonka & Stuetzer, 2017). | Risk taking | The probability or propensity of a person to take risks (Rauch & Frese, 2007a). |

| Internal locus of control | Implies that one has the belief of controlling one's destiny and future (Rotter, 1966). | |

| Self-efficacy | The belief of being able to perform a certain action effectively (Rauch & Frese, 2007a). | |

| Integral Model of Entrepreneurship (Suárez-Álvarez & Pedrosa, 2016). | Autonomy | The motivation for entrepreneurship as an attempt to achieve a certain individual freedom (Van Gelderen & Jansen, 2006). |

| Self-efficacy | The conviction that one can organize and execute actions efficiently as well as persist when faced with obstacles to produce desired outcomes (Costa et al., 2013). | |

| Innovation | Willingness and interest in new ways of doing things (Rauch & Frese, 2007b). | |

| Internal locus of control | The causal attribution that the consequences of a behavior are dependent on oneself (Chell, 2008; Rauch & Frese, 2007b; Suárez-Álvarez et al., 2013). | |

| Achievement motivation | The desire to achieve standards of excellence (Rauch & Frese, 2007b; Suárez-Álvarez, Campillo-Álvarez, Fonseca-Pedrero, García-Cueto, & Muñiz, 2013). | |

| Optimism | A person's beliefs regarding the occurrence of positive rather than negative events in his or her life (Shepperd et al., 2002). | |

| Stress tolerance | Resilience to perceive environmental and stressful stimuli through the appropriate use of coping strategies (Lazarus & Folkman, 1986). | |

| Risk taking | The tendency and willingness of people to face certain levels of insecurity that will allow them to achieve a goal that presents benefits greater than the possible negative consequences (Moore & Gullone, 1996). |

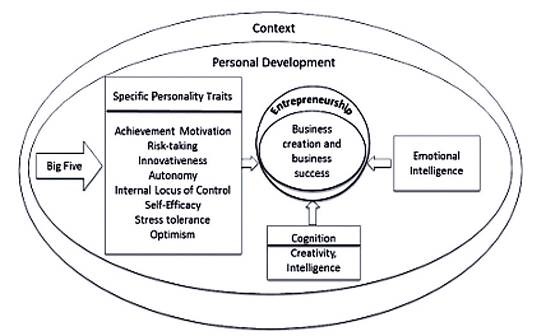

The last model presented in Table 1, by Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa (2016), establishes that eight personality traits are related to entrepreneurial activity. Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa (2016)consider that specific personality traits, influenced by more general personality traits, influence entrepreneurial creation and success, together with cognitive and affective variables within the person's sociocultural context (Figure 2).

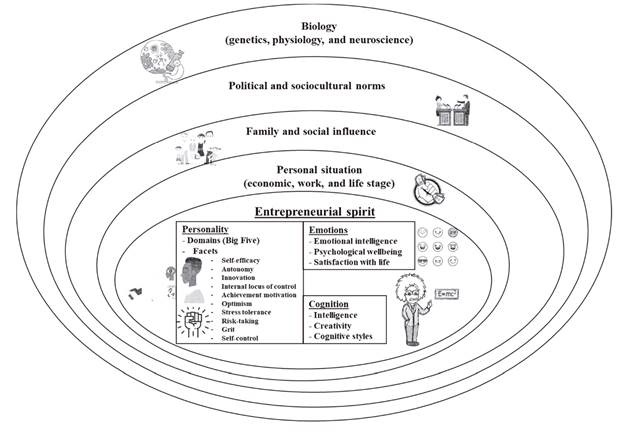

Here we present another model, based on that of Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa (2016), but adding some personal as well as contextual variables that have shown an important relationship with entrepreneurship in recent years (see, Figure 3). The model takes biology into account, so that genetics, physiology with hormones, and neuroscience with brain activity have shown certain correlational patterns in entrepreneurship (Lindquist et al., 2015; Nofal et al., 2021). Political and sociocultural norms are the broadest contextual level, where the laws, regulations, and taxes of each country or region come into play. In short, the facilities and difficulties faced by the person in the place where he or she wants to start a business. The family and the social environment of the person is also relevant in entrepreneurial activity. The family can be a source of inspiration for entrepreneurship or the opposite (Arregle et al., 2015; Erdogan et al., 2020). In turn, many entrepreneurs inherit family businesses, helping to overcome the difficulties of the first stages of the entrepreneurial path. Next, there is the person's current situation, both economically and in terms of employment. The economic level of the person and the work situation (having or not having a job, stability, salary, and satisfaction with the job and with the organization, etc.) are relevant variables when making the decision to become an entrepreneur or not. Once this has been contemplated, there is the personal part, characterized by the psychological variables relevant to entrepreneurial activity. The cognitive perspective (intelligence, creativity, and cognitive styles) and the affective perspective (emotional intelligence, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction) help to explain entrepreneurial creation and success. Finally, the importance of the personality of individuals is highlighted. This is considered both from the breadth of the domains, Big Five type, and the fidelity of the facets (including grit, self-control, and the eight traits of the model of Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa, 2016).

Within the whole model, it is worth highlighting the two traits that are added to the entrepreneurial personality: grit and self-control. Both traits are considered facets of the Big Five trait Conscientiousness, one of the general traits that has shown the strongest relationship with entrepreneurship (Zhao et al., 2010). Grit is the one that has experienced the greatest boom in recent years in the study of entrepreneurial activity.

Grit is a concept that was rebornin 2007, after a study by Duckworth et al. (2007). Grit is defined as passion and perseverance for long-term goals (Duckworth, 2016; Duckworth et al., 2007). Specifically, "grit involves working strenuously toward challenges, maintaining effort and interest for years despite failure, adversity, and stagnation in progress. The person with high levels of grit approaches achievement like a marathon; his or her advantage is endurance" (Duckworth et al., 2007, p. 1087). This construct is composed of two dimensions, perseverance of effort and consistency of interest. Duckworth et al. (2007)studied grit in different contexts (e.g. school and military), finding that it shows incremental validity of different measures of success (e.g. academic performance) over IQ and Conscientiousness of the Big Five model. Within the organizational context, grit predicts job satisfaction and pay, as well as job tenure (Danner et al., 2020; Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014; Farina et al., 2019; Salles et al., 2017). In the entrepreneurial context, grit predicts entrepreneurial creation and success (Arco-Tirado et al., 2019; Mooradian et al., 2016; Mueller et al., 2017; Postigo, Cuesta, & García-Cueto, 2021) in addition to the job performance of workers (Dugan et al., 2019; Jordan et al., 2019). The idea is that the entrepreneurial process is fraught with challenges (Cardon & Patel, 2015) and people with higher levels of grit are more likely to interpret obstacles as problems to be solved rather than reasons to quit (Southwick et al., 2021; Yeager & Dweck, 2020).

It goes without saying that the term grit has not come out of nowhere, but that other researchers in the business world had already spoken previously of the importance of passion, interest, and effort (e.g. Baum & Locke, 2004). In fact, Eskreis-Winkler et al. (2016, p. 380)note that "grit has a short history but a long past" and its origins go back to Galton and Cox's observation that perseverance and persistence are key characteristics shared by successful people.

Entrepreneurial Personality Assessment Instruments

In the past decade, the development of instruments that integrate the assessment of entrepreneurial personality traits in one single instrument has been dizzying. Table 2presents the main entrepreneurship assessment measurement instruments developed to date. First of all, it should be said that this Table 2is a continuation of the information provided by Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa (2016)where the authors presented seven entrepreneurial personality assessment instruments. Today, the table has doubled in size, which is good evidence of the boom of assessment in the field of entrepreneurship. These scales are oriented towards the evaluation of different groups such as adolescents (Muñiz et al., 2014; Oliver & Galiana, 2015), university students (Caird, 2006; Oliver & Galiana, 2015), and workers (Almeida et al., 2014; Cuesta et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 1991).

Table 2. Entrepreneurial Personality Measurement Instruments.

| Name | Dimensions | Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation [EAO]. | Motivation, innovation, perceived personal control, and perceived self-esteem in business. | 75 | Robinson et al. (1991) |

| Entrepreneurial Aptitude Test [TAI in Italian]. | Goal orientation, leadership, adaptation, achievement motivation, self-fulfillment, innovation, flexibility and autonomy. | 75 | Favretto et al. (2003) |

| Skills Confidence Inventory [SCI]. | Realistic, investigative, artistic, social, entrepreneurial, and conventional. | 60 | Betz et al. (2005) |

| General Enterprising Tendency [GET2]. | Need for achievement, autonomy, determination, risk-taking, and creativity. | 54 | Caird (2006) |

| Entrepreneurial Intention Questionnaire [EIQ]. | Professional attractiveness, social valuation, and entrepreneurial capacity and intention. | 20 | Liñán & Chen (2006) |

| Cuestionario de Orientación Emprendedora [Entrepreneurial Orientation Questionnaire, COE in Spanish]. | Locus of control, self-efficacy, risk propensity, and proactivity. | 34 | Sánchez, (2010) |

| Measure of Entrepreneurial Tendencies and Abilities [META]. | Creativity, opportunism, proactivity, and vision. | 44 | Almeida et al. (2014) |

| Battery for the Evaluation of Entrepreneurial Personality in Youth (BEPE-J) | Self-efficacy, autonomy, innovation, internal locus of control, achievement motivation, optimism, stress tolerance, and risk taking. | 87 | Muñiz et al. (2014) |

| Escala de Actitudes Emprendedoras para Estudiantes[Entrepreneurial Attitudes Scale for Students, EAEE in Spanish]. | Proactivity, professional ethics, empathy, innovation, autonomy, and risk taking. | 18 | Oliver & Galiana (2015) |

| Entrepreneurial Mindset Profile [EMP]. | Personality traits: Independence, limited structure, nonconformism, risk acceptance, action orientation, passion, and need for achievement. Skills: Future focus, idea generation, execution, self-confidence, optimism, persistence, and interpersonal sensitivity. | 72 | Davis et al. (2016) |

| High Entrepreneurship, Leadership and Professionalism Questionnaire [HELP]. | Entrepreneurship, leadership, and professionalism. | 9 | Di Fabio et al. (2016) |

| Role Related Personal Profile [FLORA] | Extraversion (Interaction, Multitasking, Initiative, Activism, Influence, Leadership, Autonomy). Sociability (Interpersonal sensitivity, Affection, Collaboration, Support, Positive affectivity). Conscientiousness (Reliability, Consistency, Accuracy, Deliberation, Achievement). Openness (Learning, Inventive, Deepening, Flexibility). Emotional stability (stress tolerance, frustration tolerance, self-control). | 176 | Sartori et al. (2016) |

| Batería para la Evaluación de la Personalidad Emprendedora[Battery for the Evaluation of Entrepreneurial Personality in Adults, BEPE-A in Spanish] | Self-efficacy, autonomy, innovation, internal locus of control, achievement motivation, optimism, stress tolerance, and risk taking. | 80 | Cuesta et al. (2018) |

| MindCette Entrepreneurial Test [MCET]. | Confidence, diligence, entrepreneurial desire, innovation, leadership, motivation, permanence, resilience, and self-control. | 38 | Shaver et al. (2019) |

Note.Expanded and updated from Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa (2016).

What is striking is not so much the type of dimensions, but the disparity in the number of traits measured by each instrument. Thus, one could go from the HELP (Di Fabio et al., 2016) with only three dimensions to the EMP (Davis et al., 2016) with 14. Furthermore, the EMP stands out for its distinction between skills, such as idea generation, and between personality traits, such as the need for achievement, the latter being better predictors of entrepreneurial behavior. The instruments also differ in terms of the number of items, ranging from nine items (HELP; Di Fabio et al., 2016) to the 176 items of FLORA (Sartori et al., 2016). On the other hand, the only ones developed in Spain are the Cuestionario de Orientación Emprendedora[Entrepreneurial Orientation Questionnaire], the Escala de Actitudes Emprendedoras para Estudiantes[the Entrepreneurial Attitudes Scale for Students] and the Batería para la Evaluación de la Personalidad Emprendedora[Entrepreneurial Personality Assessment Battery], both in its version for adolescents and adults, although others have been translated and adapted from different cultures (Almeida et al., 2014; Caird, 2006; Liñán & Chen, 2006). In contrast, the FLORA (Sartori et al., 2016) was constructed from the Big Five perspective, but in turn, it breaks down each general trait into certain specific traits or facets (see Table 2). The MCET (Shaver et al., 2019) assesses ten dimensions; however, it lacks a detailed explanation of the instrument construction process. Finally, the BEPE-A (in adults, Cuesta et al., 2018), which originated as the BEPE-J (in youth, Muñiz et al., 2014), assesses eight specific personality traits.

Characteristics of the Entrepreneurial Personality Instruments

Now that the current instruments for measuring entrepreneurial personality have been identified, an indicative overall assessment of the quality of these instruments is produced according to the criteria established by the European Federation of Psychologists' Associations (EFPA) for the evaluation of tests (Evers et al., 2013) and the Standards for Educational and Psychological Assessment (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education [AERA, APA, NCME], 2014).

First, as indicated by Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa (2016), it is striking that, although some authors mention evidence of content validity, few provide data based on expert judgments and quantitative indicators (Pedrosa et al., 2014; Sireci & Faulkner-Bond, 2014). However, it is true that more recent measurement instruments seem to pay more attention to this aspect during the construction process (Davis et al., 2016; Di Fabio et al., 2016; Oliver & Galiana, 2015). Other aspects that have scarcely been contemplated are the study of differential item functioning (DIF) and measurement invariance. In the case of DIF, only the BEPE has taken it into account, both in its version for adolescents (Muñiz et al., 2014) and in its version for adults (Cuesta et al., 2018). Even more neglected is measurement invariance, since only the BEPE in its adult version has analyzed this psychometric aspect (Postigo et al., 2023). Both are essential, since they make it possible to identify, roughly speaking, whether the content of the items that make up the instrument is biased and, therefore, prejudices a certain group, whether men or women, young people or adults, entrepreneurs or non-entrepreneurs, among other possible populations (Pendergast et al., 2017; Sandilands et al., 2013; Zumbo, 2007). Finally, despite the advances enabled by item response theory (IRT) in psychological assessment (Van der Linden, 2016), it seems that only the BEPE in youth and adults has been developed based on this methodological framework, developing a computerized adaptive test in both populations (Pedrosa et al., 2016; Postigo, Cuesta et al., 2020). Finally, the instruments with a smaller number of items are the EIQ (Liñán & Chen, 2006) with 20 items, the EAEE (Oliver & Galiana, 2015) with 18, and the HELP-Q (Di Fabio et al., 2016) with nine items. However, these instruments, despite having few items, do not offer a total score of entrepreneurial personality, limiting themselves to assessing each of the dimensions of which they are composed with a small number of items. Of the instruments with a high number of items, the BEPE has been developed in a short version, which assesses entrepreneurial personality with 16 items, two items per specific dimension, with the aim of covering the greatest possible content of the eight entrepreneurial personality traits of which it is composed (BEPE-16; Postigo, García-Cueto et al., 2020). Table 3shows the strengths and weaknesses of each entrepreneurial personality assessment instrument mentioned above. With respect to Spain, there are currently at least six measuring instruments for assessing entrepreneurial personality, either developed in Spain or translated and adapted from other countries and cultures: EIQ (Liñán & Chen, 2006); COE (Sánchez, 2010); META (Almeida et al., 2014)., EAEE (Oliver & Galiana, 2015), and BEPE-J (Muñiz et al., 2014) and BEPE-A (Cuesta et al., 2018). It is important to highlight that, to our knowledge, the META offers only a translation of its items into Spanish, which is not enough to confirm its reliable and valid use in the Spanish context (Hernández et al., 2020; Muñiz et al., 2013).

Table 3. Psychometric Properties of the Different Entrepreneurial Personality Assessment Instruments.

| Test | Reliability | Evidence of validity: Content | Evidence of validity: Construct | Evidence of validity: Criterion | DIF | Measurement invariance | TAI | Short version | Available in Spanish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAO | √ | √ | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| CAT | √ | x | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| SCI | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| GET2 | √ | x | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| EIQ | √ | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | √ |

| COE | √ | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | √ |

| META | √ | x | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | √ |

| BEPE-J | √ | √ | √ | x | √ | x | √ | x | √ |

| EAEE | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | √ |

| EMP | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| HELP | √ | √ | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| FLORA | √ | x | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | x |

| BEPE-A | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| MCET | √ | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Present Limitations and Future Lines

The first limitation in the study of entrepreneurial personality is the difficulty in differentiating a person who starts a business because he or she wants to from the person who starts a business because he or she needs to, as the outcomes can be (and are) very different (Henrekson & Sanandaji, 2014). Future studies should differentiate innovative entrepreneurs, i.e., those who have a business idea and start it, from subsistenceentrepreneurs, who see entrepreneurship as the only possible way to join or rejoin the labor market (GEM, 2020, 2021; OCDE, 2019). It is recalled that more than 70% of Spaniards started a business in 2020 due to the lack of employment opportunities (GEM, 2021). Also, most studies focus only on what is known as the extra-entrepreneur (Rauch & Frese, 2007b) or "general entrepreneur"−someone who chooses to work for himself or herself rather than for others. However, as we have seen, the very definition of an entrepreneurial person includes other types of entrepreneurs (e.g., intrapreneur). Thus, a person may claim to be an employee, but in reality he or she is in charge of entrepreneurship and innovation within his or her company. Likewise, no distinction is usually made between extra-entrepreneurs, and the terms "entrepreneur" and "self-employed" are used interchangeably. Future studies should differentiate entrepreneurs by type of business (e.g. technology vs. franchise) and motivation for entrepreneurship (those who have had to become entrepreneurs due to unemployment or immigration vs. those who have not).

Secondly, and following a limitation already pointed out by Suárez-Álvarez and Pedrosa (2016), the data collected on the different samples tend to be obtained through self-reports. When employing this methodology, it is assumed that there may be certain biases on the part of the participants when answering the items. Two examples of these biases would be acquiescence (agreeing with the wording of the items) and social desirability (wanting to give a positive self-image), which have been shown to have some influence on personality testing (Ferrando & Navarro-González, 2021; Navarro-González et al., 2016; Vigil-Colet et al., 2013). In recent years, attempts have been made to propose solutions such as implicit association tests (IATs), which allow the assessment of attitudes and beliefs through the strength of the automatic association between mental representations of concepts in memory (Greenwald et al., 2009). However, these attempts seem not to have worked in the field of entrepreneurial personality (Martínez-Loredo et al., 2018). A possible future line in the assessment of entrepreneurial personality is the use of situational judgment and forced-choice tests (Abad et al., 2022; Kyllonen, 2015; Murano et al., 2021), which can be very useful in the complex contexts in which entrepreneurial personality is assessed (grant-giving entities, recruitment firms, etc.) where the influence of social desirability is evident.

Thirdly, the IATs assessing entrepreneurial personality to date (Pedrosa et al., 2016; Postigo, Cuesta et al., 2020) are based on a unidimensional model, leaving out important information regarding traits and facets. Future lines should be directed towards multidimensional item response theory (MIRT) models and develop a multidimensional computerized adaptive version, to enable an adaptive profile of entrepreneurial personality based on the IRT approach. Multidimensional adaptive assessment has been receiving special attention for some years now (Frey & Seitz, 2009; Reckase, 2009), and the generation of an algorithm to assess all specific traits in an adaptive manner is an interesting future line of research.

Fourthly, it appears that measurement invariance has only been studied in two groups in relation to age and to being an entrepreneur or not. With regard to age, only two groups were taken into account, with the cut-off point being 30 years of age (Postigo et al., 2023). Future data collection should take this aspect into account, studying measurement invariance and differences in entrepreneurial personality across the different stages of life (Zacher et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021) or, at least, contemplating the age cut-off points set by major international reports such as the GEM report (18-24; 25-34; 35-44; 45-54; 55-64 years; GEM, 2020, 2021).

Finally, one of the limitations of most of the studies is that they have studied the entrepreneurial personality in a practically isolatedmanner, neglecting the cognitive, affective, and contextual variables of individuals. Future studies should include, on the one hand, other personal characteristics by addressing other approaches such as the aptitudinal or cognitive (Mitchell et al., 2021; Sternberg, 2004) and affective (Baron & Branscombe, 2017; Baron et al., 2012) and, on the other, contextual and biographical variables. Contemplating the seas in which the entrepreneur navigates becomes a fundamental task in order to understand well what drives entrepreneurs to start a business. Attention must be paid to factors such as the opportunities and resources available to the person, culture, laws, and even family influence, which are essential aspects in the study of the entrepreneur. Lastly, among the emerging topicson the subject of entrepreneurship (Cardon et al., 2021) are entrepreneurial teams. Entrepreneurship research has traditionally implied that a new venture is founded by a single person, whereas awareness is emerging that many companies are founded by entrepreneurial teams, formed by two or more individuals pursuing the same business idea (Breugst & Preller, 2021; Jin et al., 2017; Lazar et al., 2020). In view of all this, we will see what the field of entrepreneurial personality has in store for us in the next five years.