Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.96 no.1 Madrid ene. 2004

| ORIGINAL PAPERS |

Endoscopic resection of large colorectal polyps

F. Pérez Roldán, P. González Carro, M. L. Legaz Huidobro, M. C. Villafáñez García1, S. Soto Fernández,

A. de Pedro Esteban, O. Roncero García- Escribano and F. Ruiz Carrillo

Service of Digestive Diseases. Department of Internal Medicine. 1Emergency Department. Complejo Hospitalario

La Mancha-Centro. Alcázar de San Juan, Ciudad Real. Spain

ABSTRACT

Backgrounds: endoscopic polypectomy is a common technique, but there are discrepancies over which treatment -surgical or endoscopic- to follow in case of polyps of 2 cm or larger.

Objectives: to analyse the efficacy and complications of colonoscopic polypectomy of large colorectal polyps.

Patients and methods: 147 polypectomies were performed on 142 patients over an eight-year period. The technique used was that of submucosal adrenaline 1:10000 or saline injection at the base of the polyp, followed by resection of the polyp using a diathermic snare in the smallest number of fragments. Remnant adenomatous tissue was fulgurated with an argon plasma coagulator. Lately, prophylactic hemoclips have been used for thick-pedicle polyps.

Complete removal was defined as when a polyp was completely resected in one or more polypectomy sessions. Polypectomy failure was defined as when a polyp could not be completely resected or contained an invasive carcinoma.

Results: the mean patient age was 67.9 years (range, 4-90 years), with 68 men and 79 women. There were 74 sessile polyps, and the most common location was the sigmoid colon. The most frequent histology was tubulovillous. Most of the polyps (96.6%), were resected and cured. This was not achieved in four cases of invasive carcinoma, and a villous polyp of the cecum. All pedunculated polyps were resected in one session, whereas the average number of colonoscopies for sessile polyps was 1.35 ± 0.6 (range, 1-4). The polypectomy was curative in all of the in situ carcinomata except one. As for complications, 2 colonic perforations (requiring surgery) and 8 hemorrhages appeared, which were controlled via endoscopy. There was no associated mortality.

Conclusions: endoscopic polypectomy of large polyps (≥ 2 cm) is a safe, effective treatment, though it is not free from complications. Complete resection is achieved in a high percentage, and there are few relapses. It should be considered a technique of choice for this type of polyp, except in cases of invasive carcinoma.

Key words: Colonoscopy. Polipectomy. Larges polyps. Colorectal.

Pérez Roldán F, González Carro P, Legaz Huidobro ML, Villafáñez García MC, Soto Fernández S, de Pedro Esteban A, Roncero García-Escribano O, Ruiz Carrillo F. Endoscopic resection of large colorectal polyps. Rev esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 36-47.

Recibido: 29-05-03.

Aceptado: 03-09-03.

Correspondencia: Francisco Pérez Roldán. Unidad de Aparato Digestivo. Servicio de Medicina Interna. Complejo Hospitalario La Mancha-Centro. Avda. de la Constitución, 3. 13600 Alcázar de San Juan, Ciudad Real. Tfno.: 926 580 735/753. Fax: 926 547 700. e-mail: perezrold@teleline.es

INTRODUCTIÓN

Initially, gastrointestinal endoscopy represented a useful diagnostic tool for digestive tract diseases. Yet, ever since Wolff and Shinya (1) introduced endoscopic polypectomy in the 1970's, treatment of colorectal polyp has undergone a significant progress.

Endoscopic polypectomy is becoming increasingly safe and ambitious, although this treatment comes with a price tag: complications secondary to polypectomy. These complications are more frequent in sessile polyps, and in those over 2 cm in size. They can generally be grouped into two types: hemorrhages (0.8-1.5%) and perforation (0.25-0.5%) (2,3-6).

There are several techniques for resection, but it generally consists of a submucosal 1:10,000 adrenaline or saline injection at the base of the polyp, followed by resection of the polyp using a diathermic snare (7-10). Recently, argon plasma coagulators have been introduced to fulgurate large polyp remnants or for hemostasis with very positive results (11,12).

This study aims to show a retrospective series endoscopic resections of large polyp, describing the efficacy and complications that have emerged.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between January 1995 and December 2002, 8,175 colonoscopies were performed, 882 of which had an associated polypectomy. Of these polypectomies, 147 were performed on large polyps, those measuring 2 or more centimetres regardless of whether they were sessile or pedunculated (approximately 13%). An open-biopsy forceps was used as a reference to measure polyp size.

The colon was prepared following a standard procedure with a fibre- and residue-free diet within 48 hours of colonoscopy, later adding an osmotic laxative (senosides or phosphates). The colonoscopy was performed according to the standard procedure using Olympus CF-130HL, CF-VL, CF-Q140L and CF-Q145L videocolonoscopes, the latter being used only in 2002 (Olympus Optical Co, Hamburg, Germany). As electrocoagulation sources, an Erbe HF-100 Olympus Europe model knife was initially used. As of 1998, a Söring Arco-2000 model argon-gas knife was used (Söring Medizintechnik, Hamburg, Germany). The sclerosis needle and endoscopic snare used were standard models. Disposable models were used since 2000.

The technique used was an injection of diluted adrenaline -1:10,000- at the base of the pedicle, or a submucosal injection for sessile polyps. If a sessile polyp was larger than 3 cm it was raised with saline to a variable volume. It was then resected with a diathermic snare, in one fragment if possible, or otherwise with the smallest possible number of fragments (piecemeal resection), with a later attempt to recover them all (Fig. 1).

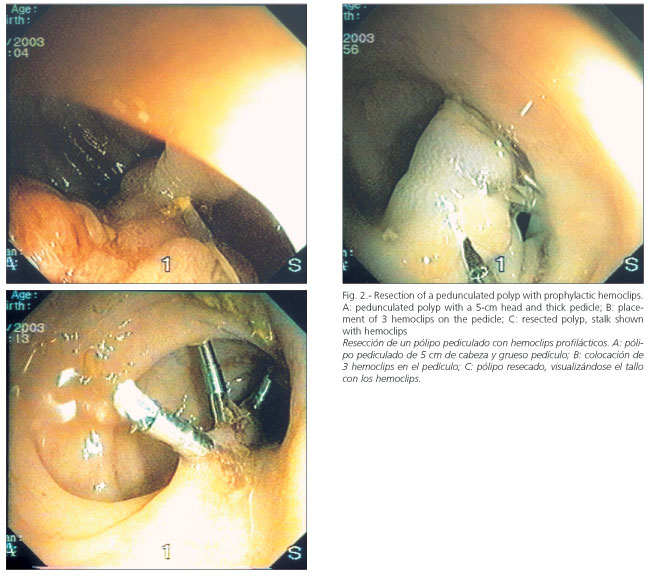

Remnant adenomatous tissue was fulgurated with an argon plasma coagulator. An injection of diluted epinephrine at a concentration of 1:10,000, and occasionally an endoloop for pedunculated polyps, was used as a prophylactic measure to prevent postpolypectomy bleeding. Starting in 2002, hemoclips have been used prophylactically for thick-pedicle polyps prior to resection with an endoscopic snare (Fig. 2). Polypectomy sites were not marked with India ink, nor was chromoendoscopy used in the diagnosis of residual polyps, except in 2002.

Once the polyp was recovered, it was sent to thepathology department for analysis, being histologically classified into hyperplastic, tubular, villous or mixed categories, and checked for dysplasia and carcinoma, and if present, whether it was in situ or invasive. A miscellaneous group of polyps included juvenile, hamartomatous, inflammatory, and lipomatous polyps.

Polyp removalwas defined as the complete resection in either one or several polypectomy sessions, regardless of the endoscopic technique used. Further, in the case of sessile polyps, it was necessary to attain endoscopic and histological proof that no residual polyp existed. Polypectomy failure was defined as cases in whom polyps could not be completely resected and had to be referred to surgery, those who withdrew from endoscopic treatment or those that had invasive carcinoma. Finally, polyp relapsewas defined as the appearance of a polyp or neoplasm at the previous polypectomy site during follow-up.

The follow-up of completely resected polyps (removal of polyps) varied depending on their histology:

-If there was no severe dysplasia or carcinoma,the patient was considered to be cured, and checkups were carried out depending on the type of polyp. For non-adenomatous polyps it varied depending on the underlying illness: for tubular adenomas, sessile polyps were checked every 6 months, and pedunculated polyps at 12 months (if the patient evolved correctly, they were che-cked again every 1-2 years); villous and tubovillous adenomas were checked at 6 and 12 months the first year. If the patient evolved correctly, they were checked again every 1-2 years.

-If a severe dysplasia or in situcarcinoma appeared, and the edge of the resection was clear, polyps were considered to be removed and checkups were scheduled at 3, 6 and 12 months. If the patient evolved correctly, the checkup was annual. If the edge of the resection was affected, resective surgery was recommended. But for those patients with severe associated illnesses, or those who refused to follow this recommendation, the eschar was checked at 1-2 months and biopsies were taken. If the biopsies were negative, a follow-up at three-month intervals was conducted over one year. If biopsies tested positive for malignancy, patients were referred to surgery unless they specifically refused.

-If an invasive carcinoma appeared, patients were referred to surgery for resection unless they specifically refused.

Finally, the Rsigmastatistical programme was used to construct the database, and for the statistical analysis of both parametric and non-parametric variables.

RESULTS

One hundred and forty-seven large polyps were resected from 142 patients in this period. During follow-up, polyps (of any size) appeared in 96 patients (67.6%). The number of polyps that were discovered and resected during follow-up was 2.6 ± 2.09 (range, 1-11). In this study, mean follow-up lasted 43.27 ± 24.8 months (range, 7-97 months).

The mean patient age was 67.9 ± 12.6 years (range 4-90 years). No gender differences existed. Polypectomies were carried out on 68 men and 79 women (53.7%).

The reasons for polypectomy were varied: 127 polyps (86.4%) were resected merely because their presence was detected, 12 polyps (8.2%) appeared during the follow-up of patients who had had colon cancer operations, and eight polyps (5.4%) were resected prior to the surgical resection of a colon neoplasm, so that a less extensive and mutilating surgery could be carried out.

As for polyp type, there were 73 pedunculated and 74 sessile polyps. Generally, the mean number of colonoscopies needed to resect the polyps was 1.17 ± 0.49 (range, 1-4). All of the pedunculated polyps were resected in a single session. In cases of sessile polyps, the mean number of colonoscopies was 1.35 ± 0.6 (range, 1-4); polyps <4 cm required 1.11 ± 0.32 (range, 1-2) colonoscopies for complete resection. Sessile polyps of 4 cm or more in size required 1.76 ± 0.86 colonoscopies (1-4) for complete polypectomy.

The most frequent location of these polyps was the sigmoid colon, as is shown in table I. As expected, 50% of polyps were smaller than 3 cm, and 15% had a size over 5 cm (Table II).

The most frequent histological type was tubulovillous adenoma for both pedunculated and sessile polyps, as shown in table III. There were 23 in situ carcinoma (96.6% cured) and 4 invasive carcinomas. Of them, three received surgery, and one patient refused. In the miscellaneous polyp group, there was a hamartoma, an inflammatory polyp, 2 juvenile polyps, and one inflammatory polyp with moderate dysplasia in a patient with ulcera-tive colitis. Slight or moderate dysplasia appeared in 35 polyps of the 114 which had tubular, villous or tubulovillous histology (19 pedunculated and 16 sessile).

In terms of complications, there were eight hemorrhages (5.4%) and two perforations (1.3%). Four of these hemorrhages appeared in pedunculated polyps, and the rest of complications arose with sessile polyps. One of the perforations occurred in a 4x3 cm sessile polyp at the splenic flexure that could not be sealed with hemoclips, and the other in a 7 cm sessile polyp located in the rectum-sigmoid colon, which was seen to be an invasive carcinoma (prior biopsies showed a villous adenoma with moderate dysplasia). Surgery was only required for the two perforations, and there was no associated mortality. Regarding hemorrhages, one appeared in a thick pedicle that was controlled with an 1:10,000 adrenaline injection and with argon. The other seven hemorrhages were treated with 1:10,000 adrenaline in four cases, argon in two cases, and in one case with the use of hemoclips. Hemoclips have been recently used on 4 pedunculated polyps to prevent bleeding, and no complications have arisen.

The efficacy of polypectomy varied depending on the polyp -whether it was pedunculated or sessile- although in general terms 142 polyps (96.59%) were resected. All pedunculated polyps were resected, with complete removal in 100% of cases regardless of size. There was no tumoural invasion of the pedicle in any of the cases. As regards sessile polyps, five patients had incomplete resections: one 7 cm villous polyp of the cecum and four invasive carcinomata. Overall, five patients required surgery:

-Perforation of a tubulovillous adenoma: suture of perforation and complete resection of polyp checked.

-Two centimeters invasive carcinomata in the rectum: lower anterior resection and complete resection checked by endoscopy.

-2.5 cm invasive carcinoma in the descending colon: hemicolectomy with failed polypectomy.

-Seven centimeters invasive carcinoma in the rectum (perforation): lower anterior resection, with failed polypectomy.

-Failed polypectomy on a 7centimeters villous polyp of the cecum: hemicolectomy.

One patient with an in situ carcinoma refused to have surgery following an initial incomplete resection (elderly, pluripathological patient); he had a relapse of invasive carcinoma at 12 months. In addition, this patient had an invasive carcinoma that was partially resected and fulgurated with argon, but without success. The patient required a colon prosthesis to palliate obstruction one year after initial diagnosis. The patient died six months after a prosthesis was implanted from tumoural dissemination and old age.

The most commonly used technique was endoscopic snare resection prior to the injection of diluted adrenaline (79.6%), particularly in pedunculated polyps. In large sessile polyps, a saline injection followed by piecemeal polyp resection was frequently used. An associated treatment was required by 36.74% of patients, argon being most frequently used, above all in sessile polyps (55.4%).

DISCUSSION

Ever since the introduction of endoscopic polyp resection in the 1970's by Wolf and Shinya (1), endoscopic polypectomy has become a common technique in any Department of Gastroenterology. Large polyps represent a treatment challenge, and there are discrepancies on how to proceed. Some authors believe that surgery is best due to the problems associated with endoscopy, such as being a risky procedure, the possibility for inadequate endoscopic resection, and the high possibility of a co-existing malignancy. Various authors consider these polyps to be most difficult and dangerous for endoscopic resection. They tend to require piecemeal resection. Therefore, their endoscopic treatment is a controversial issue (2,7-18).

The fact that surgery has higher mortality (2-4%) and morbidity (10%) rates than endoscopic polypectomy cannot be overlooked (11). On the other hand, some of the surgical procedures carried out require a permanent or temporary colostomy, with an obvious impact on the patient's quality of life, along with their inherent morbidity/mortality.

Large polyps are understood to be pedunculated or (more frequently) sessile polyps of 2 or more centimetres in diameter, as later described by Christie (2) and others (11). Few published studies evaluate the endoscopic treatment of these polyps and its efficacy, safety, and cost as compared to surgery. Table IV lists data for an analysis of the main series published so far (4,5,7,8,11-18), including that of our hospital.

The usual resection method is resection using an endoscopic snare. This is generally associated with an injection of 1:10,000 or 1:20,000 adrenaline (up to 10 mL) at the polyp base to prevent potential haemorrhage follow-ing resection (7-9). Efficacy has also been proven for the submucosal injection of saline alone (even in volumes over 20 mL) or associated with epinephrine to raise the polyp, thus facilitating its piecemeal resection in fragments which should range from 1 to 2.5 cm in size (3,10,13,14). In this study we used 1:10,000 adrenaline for both pedunculated and sessile polyps ≤3 cm in size. For polyps >3 cm we used a submucosal saline injection, with a very high complete resection rate.

In order to prevent relapses of resected polyps, or residual tissue remaining above all in sessile polyps, the fulguration of the polyp base with argon gas following resection with a diathermic snare (12) has been introduced, with good results. Since argon was introduced in 1998 to supplement edge and residual tissue resection in sessile polyps, fewer colonoscopies have been needed for complete removal. An examination of resection margins using chromoscopy with indigocarmine or water-immersion endoscopy has been shown to be helpful to complete the eradication of residual polyps. Recently, the introduction of high-magnification to complete polypectomy may prevent polyp recurrence (19).

The localisation of an exact polypectomy site for later biopsy taking (mainly for sessile polyps with in situ carcinoma) may be achieved via the injection (tattoo) of India ink at the resection site. India ink tattooing of the colon is a safe, accurate and reliable method to facilitate future endoscopic localisation as well as to mark lesions prior to surgery (20-23). India ink tattoos were only used in 2002, with highly positive results during later follow-up.

Additionally, the use of vital stains allows a more precise viewing of sessile polyp edges (especially on flat polyps), thus facilitating a complete resection of these polyps. The most widely used stain is indigocarmine, (19,24) which we used in our department all over the past year.

Endoscopy may be used to measure the depth or degree of polyp invasion into the colon wall. Its effectiveness has been proven for villous sessile polyps over 2 cm in size (24,26) as it allows the integrity of the third hyperechogenic (submucosal) layer to be viewed. This makes it possible to visualize tumour accessibility to local treatment (endoscopic polypectomy or locally via transanal excision), or otherwise the advanced T2-T3 stage of the lesion. Nevertheless, endoscopy cannot detect focal malignity limited to the mucosa and muscularis mucosae. The efficacy of endoscopic ultrasonography for the follow-up of resected polyps with in situ carcinoma should not be overlooked. Surgery must be indicated for cases where tumor invasion breaks and goes beyond the submucosa.

Large polyp polypectomy has different degrees of efficacy depending on the type of polyp resected (whether they are pedunculated or sessile (7,11,12,14-18). Overall efficacy ranges from 74% according to Brooker (18) to 100% according to Kanamori (15), as shown in table IV. For pedunculated polyps, a complete resection is reached in virtually 100% of cases, including those that must be resected in a piecemeal fashion due to their size. An exception are carcinomas that invade the pedicle and surpass resection edges (7,16,17). Insofar as sessile polyps are concerned, efficacy and removal of polyps depend on various factors: (7,11-18) polyp size (8,12-15,18,20,21), resection technique (11,12) endoscopist experience (16,18) and histological type, together with the presence of an associated carcinoma (7,12, 13,16,18,20,21). The efficacy in our series was 100% for pedunculated polyps, and 93.2% for sessile polyps. There were 4 patients with invasive carcinomata who had surgery, and one patient who refused.

Finally, the complications of polypectomy should not be overlooked. Generally speaking, it is considered that a complication may arise for every 300-700 colonoscopies (3), and that these complications are directly related with the experience of endoscopist, being more frequent in polypectomies. The complications described in the literature are widely varied, with a special emphasis on hemorrhage (1-2%), intestinal perforation (0-3%), transmural burns, pneumoperitoneum, snare trapping, ileum and colon perforation, thrombophlebitis (when an intravenous catheter is present), abdominal distension, vasovagal symptoms, septicaemia, electrocardiographic changes, volvulus, and strangulation of inguinal hernia (3-6). The first four complications are clearly related to the endoscopic procedure, and particularly to the polypectomy. Hemorrhage and perforation are related to the size of the polyp, its morphology (sessile or pedunculated) and location (5,6).

Special note is to be taken of the treatment of complications, which is increasingly feasible. In post-polypectomy hemorrhages, treatment includes the strangulation of the stalk, implantation of an endoloop, injection of adrenaline or cold saline, electrocoagulation, argon plasma coagulation (12), or a combination of any of them (3,6). If these techniques do not succeed, an arterial embolisation of the point of bleeding (5) or a colonic resection (6) may be performed. In our series, we used adrenaline injection, hemoclips, or argon plasma coagulation. Over the last year of the study, we used prophylactic hemoclips on the stalk of pedunculated polyps to prevent bleeding with good results. This hemostatic method has no controlled studies to prove its efficacy. No cases of bleeding required surgery for their control.

Perforation may be treated conservatively with a simple suture or a plasty with peritoneum (3,5). In recent years, some publications have dealt with the possibility of placing hemoclips on small perforations and performing conservative treatment in selected cases. For the two perforations that occurred in our series (polyps 4 and 7 cm in size), one required a simple suture and the other a lower anterior resection because of an invasive carcinoma. All polyps were removed similary by blend coagulation and pulsed current. For both perforations, total electric power used was higher and both sessile polyps had a large basis. In fact, these two polyps had transmural burns involving the whole thickness of the intestinal wall. As for other complications, they can generally be solved with conservative treatment.

In clonclusion, the endoscopic resection of large polyps (≥2 cm in size) is a technique that is safe, effective, and less expensive than surgery, though not free from complications. It entails a high percentage of complete resections, and a low number of relapses when performed using the right technique, along with a low frequency of complications. It should be considered the technique of choice for the treatment of these types of polyps except for those including an invasive carcinoma, in which case the polyp is not completely resected and complications may appear. Such patients must be referred for laparoscopic or open surgery.

REFERENCES

1. Wolff WI, Shinya H. Endoscopic polypectomy: therapheutic and clinicopathologic aspects. Cancer 1975; 36: 683. [ Links ]

2. Christie JP. Colonoscopic excision of large sessile polyps. Am J Gastroenterol 1977; 67: 430-8. [ Links ]

3. Macrae FA, Tan KG, Willians CB. Towards safer colonoscopy: a report on the complications of 5000 diagnostic or therapeutic colonoscopies. Gut 1983; 24: 376-83. [ Links ]

4. Webb WA, McDaniel L, Jones L. Experience with 1000 colonoscopic polypectomies. Ann Surg 1985; 201: 626-32. [ Links ]

5. Nivatvongs S. Complications in colonoscopic polypectomy. An experience with 1555 polypectomies. Dig Colon Rectum 1986; 29: 825-30. [ Links ]

6. Rosen L, Bub DS, Reed JF 3rd, Nastasee SA. Hemorrhage following colonoscopic polypectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 1126-31. [ Links ]

7. Binmoeller KF, Bohnacker S, Seifert H, et al. Endoscopic snare excision of "giant" colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43: 183-8. [ Links ]

8. Hsieh YH, Lin HJ, Tseng GY, et al. Is a submucosal epinephrine injection necessary before polypectomy? A prospective, comparative study. Hepatogastroenterology 2001; 48: 1379-82. [ Links ]

9. Shirai M, Nakamura T, Matsuura A, Ito Y, Kobayashi S. Safer colonoscopic polypectomy with local submucosal injection of hypertonic saline-epinephrine solution. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89: 334-8. [ Links ]

10. Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Kitamura S, et al. Endoscopic resection of large sessile colorectal polyps using a submucosal saline inyection technique. Hepatogastroenterology 1997; 44: 698-702. [ Links ]

11. Brooker JC, Saunders BP, Shah SG, et al. Treatment with argon plasma coagulation reduces recurrence after piecemeal resection of large sessile colonic polyps: a randomized trial and recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 55: 371-5. [ Links ]

12. Zlatanic J, Waye JD, Kim PS, et al. Large sessile colonic adenomas: use of argon plasma coagulator to supplement piecemeal snare polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 49: 731-5. [ Links ]

13. Walsh RM, Ackroyd FW, Shellito PC. Endoscopic resection of large sessile colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 1992; 38: 303-9. [ Links ]

14. Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Iseki K, et al. Endoscopic piecemeal resection with submucosal saline injetion of large sessile colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 697-700. [ Links ]

15. Kanamori T, Itoh M, Yokoyama Y, Tsuchida K. Injection-incision-assited snare resection of large sessile colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43: 256-7. [ Links ]

16. Dell'Abate P, Iosca A, Galimberti A, et al. Endoscopic treatment of colorectal benign-appearing lesions 3 cm or larger: techniques and outcome. Dis Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 112-8. [ Links ]

17. Bedogni G, Bertoli G, Ricci E, et al. Colonoscopic excision of large and giant colorectal polyps. Technical implications and results over eight years. Dis Colon Rectum 1986; 29: 831-5. [ Links ]

18. Brooker JC, Saunders BP, Shah SG, Willians CB. Endoscopic resection of large sessile colonic polyps by specialist and non-specialist endoscopists. Br J Surg 2002; 89: 1020-4. [ Links ]

19. Hurlstone DP, Lobo AJ. Assessing resection margins using high-magnification chromoscopy: a useful tool after colonic endoscopic mucosal resection. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 2143-4. [ Links ]

20. McArthur CS, Roayaie S, Waye JD. Safety of preoperation endoscopic tattoo with India ink for identification of colonic lesions. Surg Endosc 1999; 13: 397-400. [ Links ]

21. Nizam R, Siddiqi N, Landas SK, Kaplan DS, Holtzapple PG. Colonic tattooing with India ink: benefits, risks, and alternatives. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 1804-8. [ Links ]

22. Fennerty MB, Sampliner RE, Hixson LJ, Garewal HS. Effectiveness of India ink as a long-term colonic mucosal marker. Am J Gastroenterol 1992; 87: 79-81. [ Links ]

23. Shatz BA, Thavorides V. Colonic tattoo for follow-up of endoscopic sessile polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc 1991; 37: 59-60. [ Links ]

24. Takahashi M, Kubokawa M, Tanaka M, Sadamoto Y, Ito K, Yoshimura R, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography features of colonic muco-submucosal elongated polyp. Endoscopy 2002; 34: 515. [ Links ]

25. Kiesslich R, von Bergh M, Hahn M, Hermann G, Jung M. Chromoendoscopy with indigocarmine improves the detection of adenomatous and nonadenomatous lesions in the colon. Endoscopy 2001; 33: 1001-6. [ Links ]

26. Catalano MF. Indications for endoscopic ultrasonography in colorectal lesions. Endoscopy 1998; 30 (Supl. 1): A79-84. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en