Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.96 no.2 Madrid feb. 2004

| RECOMENDATIONS OF CLINICAL PRACTICE |

Approaching oropharyngeal dysphagia

P. Clavé1,2, R. Terré1, M. de Kraa2 and M. Serra2

1Unit of Digestive Neurophisiology. Institut Guttmann. Badalona, Barcelona. 2Unit of Digestive Explorations. Hospital

de Mataró. Barcelona, Spain

Clavé P, Terré R, de Kraa M, Serra M. Approaching oropharyngeal dysphagia. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 119-131.

Recibido: 14-09-03.

Aceptado: 23-09-03.

Correspondencia: Pere Clavé i Civit. Unidad de Exploraciones Funcionales Digestivas. Hospital de Mataró. Consorci Sanitari del Maresme. Ctra. de Cirera, s/n. 08304 Mataró. Barcelona. Tel.: 93 741 77 00. Fax: 93 741 77 33. e-mail: pclave@teleline.es

INTRODUCTION

Dysphagia is a symptom that refers to difficulty or discomfort during the progression of the alimentary bolus from the mouth to the stomach. From an anatomical standpoint dysphagia may result from oropharyngeal or esophageal dysfunction and from other structure-related or functional causes from a pathophysiological viewpoint. The prevalence of oropharyngeal functional dysphagia is very high in patients with neurological disease: it includes more than 30% of patients having had a CVA; its prevalence in Parkinson's disease is 52-82%; it is the first symptom for 60% of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS); it affects 40% of patients with myasthenia gravis, up to 44% of patients with multiple sclerosis; up to 84% of patients with Alzheimer's disease, and more than 60% of elderly institutionalized patients (1-5). The severity of oro-pharyngeal dysphagia may vary from moderate difficulty to complete inability to swallow.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia may give rise to two groups of clinically relevant complications:

1. When a decrease in deglutition efficacy occurs, patients present with malnutrition and/or dehydration.

2. When a decrease in deglutition safety occurs, choking and airway obstruction develop, most commonly as a tracheobronchial aspiration that may result in pneumonia in 50% of cases, with an associated mortality up to 50% (1).

OBJECTIVE

To define a set of clinical recommendations aimed at facilitating the diagnosis and management of patients with functional oropharyngeal dysphagia.

METHOD

This review on the approach to functional oropharyngeal dysphagia is based on the discussion of recommendations issued within consensus papers relying on "best evidence and best medical practice" by the following groups of experts:

-AGA Technical Review on Management of Oro-pharyngeal Dysphagia (1).

-www.dysphagiaonline.com (2).

-Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. USA (3).

-Interventions for dysphagia in acute stroke. Cochrane Review (4).

-Disfagia Neurógena: Evaluación y Tratamiento. Fundació Institut Guttmann. Hospital de Neurorrehabilitación (5).

NORMAL DEGLUTITION

Normal deglutition comprises four stages; any of these stages (commonly more than just one) may be affected and result in dysphagia:

1. The oral preparatory stage is under voluntary control and is aimed at mastication and bolus formation.

2. The oral stage is also voluntary, and is characterized by bolus propulsion by the tongue.

3. The pharyngeal stage is involuntary and is triggered by an activation of pharyngeal mechanoreceptors that send information to the CNS and trigger the so-called pharyngeal deglutition motor pattern (deglutition reflex), which is characterized by an orderly sequence of consistent motor events that result in closure of the naso-pharynx (soft palate elevation) and the airway (hyoid bone elevation and anterior displacement, lowered epiglottis, and vocal cord closure), opening of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), and contraction of pharyngeal constrictor muscles. The tongue is primarily responsible for bolus propulsion, and the main goal of pharyngeal constrictor muscles is the clearance of bolus remnants within the hypopharynx.

4. The esophageal stage begins with the opening of UES, which is followed by esophageal peristalsis.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF DYSPHAGIA

Dysphagia may result from a wide range of structural alterations that may hinder or prevent oropharyngeal reconfiguration during deglutition from the airway to the alimentary canal, or hamper the bolus progression, and also functional alterations that may impair bolus propulsion of pharyngeal configuration. Most common structural abnormalities include esophageal and ENT tumors, neck osteophytes, commonly postsurgical esophageal stenosis, upper sphincter aperture disturbances (crico-pharyngeal bar, cricopharyngeal achalasia), and Zenker's diverticulum. However, oropharyngeal dysphagia is frequently a clinical manifestation of a systemic or neurological disease, or associated with ageing. Most commonly dysphagia precedes other neurological symptoms (6). Neurological disease may also bring about impairment in the function of esophageal smooth and striated muscles, or of motor neurons at the myenteric plexus, which control esophageal width and peristalsis, and the relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. In addition, esophageal dysphagia may be a common symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease, whose prevalence is also increased in a great number of patient subsets with neurogenic dysphagia.

DIAGNOSIS OF DYSPHAGIA

Dysphagia multidisciplinary team. Dysphagia units

The diagnosis and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia calls for a multidisciplinary approach. A dysphagia multidisciplinary team should be knowledgeable of a number of professional spheres and include: nurses, language therapists, gastroenterologists, ENT specialists, neurologists, rehabilitation physicians, surgeons, dieticians, radiologists, geriatrists, etc. The operativeness example set by some of these teams has revealed the small relevance of their members' baseline training, and the great significance of skill development as a group to provide coverage for the spectrum of diagnostic and therapeutic needs of patients with dysphagia by meeting common criteria. The goals of a dysphagia multidisciplinary team include: a) the identification of patients with dysphagia; b) a diagnosis of any medical or surgical etiology for dysphagia that may respond to a specific treatment, the exclusion of ENT and esophageal tumors, and the identification of gastroesophageal reflux and its complications; c) a characterization of biomechanical oro-pharyngeal changes responsible for dyaphagia in individual patients; and d) the design of a set of therapeutic strategies to provide the patient with safe and effective deglutition, or the provision of an alternative route to oral feeding based on objective and reproducible data. Family involvement in the diagnostic and therapeutic process is of paramount importance. Diagnostic and therapeutic resources are commonly concentrated in the so-called dysphagia units or centers (swallowing centers), which serve as referral institutions where patients with oro-pharyngeal dysphagia from several hospitals may be offered all the diagnostic modalities and treatments or management approaches they need.

A program for the diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia

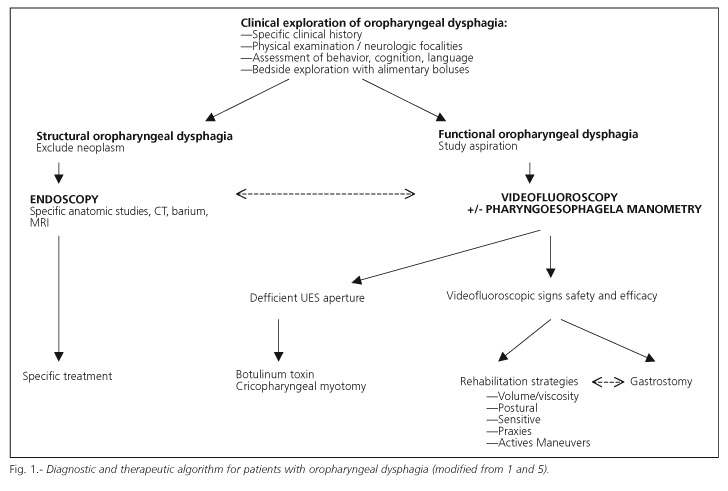

The diagnostic algorithm shown in figure 1 summarizes the diagnostic strategy for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Once structural causes have been ruled out (particularly ENT and esophageal tumors), and a diagnosis of functional oropharyngeal dysphagia has been established, the goal of the diagnostic program is to evaluate two deglutition-defining characteristics: a) efficacy, the patient's ability to ingest all the calories and water he or she needs to remain adequately nourished han hydrated; and b) safety, the patient's ability to ingest all needed calories and water with no respiratory complications. To assess both characteristics of deglutition two groups of diagnostic methods are available: a) clinical methods such as deglutition-specific medical history and clinical examination; and b) the exploration of deglutition using specific complementary studies such as pharyngoesophageal videofluoroscopy and manometry.

Clinical methods: clinical history and examination for deglutition disorders

The program for the diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia starts with clinical methods (Fig. 1). Their objective is to determine whether symptoms correspond to oro-pharyngeal dysphagia, to decide whether the patient will require complementary studies, and to identify potential nutritional and respiratory complications. The examination should include an assessment of behavioral, cognitive, and language aspects, which are needed when evaluating dysphagia mechanisms and treatment possibilities, and any neurological focalities should be definitely ruled out. The two major clinical methods are a specific clinical history and a clinical exploration of deglutition at the patient's bedside.

1. Clinical history. Dysphagia for solids suggests the presence of an obstructive difficulty, whereas dysphagia for liquids suggests the presence of a neurogenic dysphagia. Nasal regurgitation, the need for multiple swallows of a small bolus (fractioning), and a history of repeat respiratory infection also points to neurogenic dysphagia. The presence of choking, coughing or a wet voice suggests aspiration, although 40% of aspirations are silent and not associated with cough in neurologic patients (1-5). A sensation of residue in the pharynx points toward pharyngeal hypomotility, common in neurodegenerative conditions. Food regurgitation may correspond to Zenker's diverticulum. It should be remembered that the location of symptoms in the neck does not allow to differentiate between a pharyngeal or esophageal origin of dysphagia. Odynophagia suggests a pharyngeal or eso-phageal inflammatory condition or an esophageal motor disorder. Antipsychotics, sedatives and antidepressants may well play a role in dysphagia, particularly in the elderly. Nonspecific symptoms that manifest in a continuous manner and regardless of ingestion may correspond to pharyngeal globus. Increased ingestion duration and recent weight loss indicate decreased efficacy of deglutition and potential malnutrition. Nutritional status may be accurately assessed in the clinical setting with an appropriate clinical history and minimal physical examination (7). The clinical severity of dysphagia may be quantitized by using visual analog scales for a set of clinical symptoms (8).

2. Clinical examination of deglutition. An exploration of deglutition at the patient's bedside is performed by administering boluses of differing viscosity and volume, and then observing the patient's response. To select patients who will undergo complementary studies, various authors have developed methods based on the administration of a number of water sips to check whether aspiration signs arise (9). Our team developed a method for clinical examination using boluses with volumes ranging from 3 to 20 mL, and liquid, nectar and pudding viscosities (10). This technique allows the first two stages (oral preparatory, oral) of deglutition to be assessed, and we also use it as a screening method -together with the clinical history, overall neurological examination, and assessment of nutritional status- to select patients who must undergo videofluoroscopy. Although this clinical examination method may provide data on the type of bolus (volume and viscosity) that is most appropriate for the patient, it must be emphasized that patients with suspected efficacy or safety impairment should undergo videofluoroscopy (11).

Complementary examinations: videofluoroscopy and pharyngoesophageal manometry

Videofluoroscopy (VF) is a dynamic radiological technique by which a sequence of both lateral and postero-anterior images may be obtained following the oral administration of a water-soluble contrast in several volumes (3-20 mL) and 3 distinct viscosities (liquid, nectar and pudding) (11-13). It is currently considered the gold standard technique for the study of oropharyngeal dysphagia, even though information provided by pharyngoesophageal manometry is occasionally required to complement it (1,14,15). The goals of videofluoroscopy are to assess deglutition's safety and efficacy, to characterize swallowing alterations in terms of videofluoroscopic signs, to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments, and to obtain quantitative data on oropharyngeal biomechanics (11).

Videofluoroscopic signs during the oral stage

Major signs of impaired efficacy during the oral stage include apraxia and decreased control and bolus propulsion by the tongue. Many patients present with deglutitional apraxia (difficulty, delay or inability to initiate the oral stage) following a CVA. This symptom is also seen in patients with Alzheimer's dementia and patients with diminished oral sensitivity. Impaired lingual control (inability to form the bolus) or propulsion results in oral or vallecular residue when alterations occur at the base of the tongue. The main sign regarding safety during the oral stage is glossopalatal (tongue-soft palate) seal insufficiency, a serious dysfunction that results in the bolus falling into the hypopharynx before the triggering of the pharyngeal motor pattern and while the airway is still open, which causes preswallowing aspiration.

Videofluoroscopic signs during the pharyngeal stage

Major videofluoroscopic signs of efficacy during the pharyngeal stage include hypopharyngeal residue and impaired aperture of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), which are studied by using pharyngoesophageal manometry in combination. Symmetric hypopharyngeal residues in both pyriform sinuses result from weak pharyngeal contraction, which is fairly common in patients with neurodegenerative disease. Patients with CVA may exhibit unilateral residue as a consequence of unilateral pharyngeal paralysis.

Videofluoroscopic signs of safety during the pharyngeal stage include a slow or uncoordinated pharyngeal motor pattern, and penetrations and/or aspirations. Penetration refers to the entering of contrast into the laryngeal vestibule within the boundaries of the vocal cords. When aspiration occurs, contrast goes beyond these cords and into the tracheobronchial tree (Fig. 2). The potential of videofluoroscopy regarding image digitalization and quantitative analysis currently allows accurate motor pattern measurements in patients with dysphagia (Fig. 3). A slow closure of the laryngeal vestibule and a slow aperture of the upper eso-phageal sphincter (as seen in figure 3) are the most characteristic aspiration-related parameters (16). When this interval is above 0.24 seconds, the possibility of an aspiration has been estimated as very high (16). Penetration and aspiration may also result from an insufficient hyoid and laryngeal elevation, which would fail to protect the airway. A high, permanent post-swallow residue may lead to post-swallow aspiration, since the hypopharinx is full of contrast when the patient inhales after swallowing, and then contrast passes directly into the airway.

Pharyngoesophageal manometry

Most useful parameters supplied by pharyngoesophageal manometry in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia include amplitude of pharyngeal contraction, extent of upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxation, amplitude and propagation of esophageal peristalsis, and the coordination thereof (14,15). In normal individuals pharyngeal contraction occurs during UES relaxation, and the high compliance of UES allows the sphincter to fully relax during the ingestion of both 1 mL and 20 mL boluses (Fig. 4A). Pharyngoesophageal manometry is essential in the differential diagnosis of UES aperture disorders seen during videofluoroscopy, and to select an appropriate treatment option.

In patients with Zenker's diverticulum, and also in patients who fail to develop this type of diverticulum but suffer from dysphagia, cricopharyngeal muscle fibers are replaced by connective tissue, which results in fibrosis and decreased sphincter compliance. In these patients manometry shows a so-called obstructive pattern (Fig. 4B) characterized by a pharyngeal wave with preserved amplitude, and a volume-dependent increase in sphincter resideual pressure (incomplete relaxation) as a consequence of high flow and resistn¡ance (17). This pattern is also seen in patients with Parkinson's disease as a result of extrapyramidal rigidity, which prevents UES relaxation (18). Many patients with neuromuscular conditions also exhibit incomplete UES aperture during videofluoroscopy. In these patients manometry shows a so-called propulsive pattern characterized by decreased (even absent) pharyngeal wave and adequate upper sphincter relaxation (Fig. 4C). These patients show incomplete UES aperture during videofluoroscopy despite normal manometric relaxation, which results from lack of strength at bolus propulsion because of a weak lingual and pharyngeal contraction.

Clinical usefulness of the videofluoroscopic diagnosis program

VF is the gold standard in the study of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Between 45 and 90% of patients with neurologic disease show impaired deglutition efficacy that may result in malnutrition and two thirds of these patients suffer from an impaired safety that may result in aspiration (2). In addition, VF may identify potential silent aspiration in 1/4 to 1/3 of such patients, which is not clinically diagnosable and therefore entails an extremely high risk of pneumonia (11).

MANAGEMENT OF OROPHARYNGEAL DYSPHAGIA

Management strategies for oropharyngeal dysphagia may be grouped into four major categories that may be simultaneously applied to the treatment of each individual patient (21). During videofluoroscopy the needed combination of strategies may be selected to compensate each patient's specific deficiency, and its usefulness to treat the patient's symptoms may be explored:

1. Postural strategies. Verticality and symmetry should be sought during the patient's ingestion. Attention must be paid to controlling breathing and muscle tone. Postural strategies are easy to adopt -they cause no fatigue- and allow modification of oropharyngeal and bolus path dimensions. Anterior neck flexion protects the airway (22); posterior flexion facilitates gravitational pharyngeal drainage and improves oral transit velocity; head rotation toward the paralyzed pharyngeal side directs food to the healthy side, increases pharyngeal transit efficacy, and facilitates UES aperture (23); deglutition in the lateral or supine decubitus protects from aspirating hypopharyngeal residues.

2. Change in bolus volume or viscosity. In patients with neurogenic dysphagia, bolus volume reductions and bolus viscosity increases significantly improve safety signs, particularly regarding penetration and aspiration. Viscosity is a physical property that can be measured and expressed in international system units by the name of Pa.s. The prevalence of penetrations and aspirations is maximal with fluids (20 mPa.s) and decreases with nectar (270 mPa.s) and pudding (3900 mPa.s) viscosity boluses (24). Modifying the texture of liquids is particularly important to ensure that patients with neurogenic or ageing-associated dysphagia remain adequately hydrated and aspiration-free (25). This may be easily achieved by using appropriate thickening agents, which are readily available nowadays.

3. Sensorial enhancement strategies. Oral sensorial enhancement strategies are particularly useful in patients with apraxia or impaired oral sensitivity (very common in elderly patients). The focus of other strategies is the initiation or acceleration of the swallowing pharyngeal motor pattern. Most sensorial enhancement strategies include a mechanical stimulation of the tongue, bolus modifications (volume, temperature, and taste) or a mechanical stimulation of the pharyngeal pillars. Acid flavours such as lemon or lime, and cold substances such as ice cream or ice, trigger the mechanism of deglutition (26). The development of physical or drug-based strategies to accelerate the pharyngeal motor pattern represents a relevant field of research for the management of neurogenic dysphagia and ageing-associated dysphagia.

4. Neuromuscular praxis. The goal is improving the physiology of deglutition (the tonicity, sensitivity, and motility of oral structures, particularly the lips and tongue, and pharyngeal structures). Lingual control and propulsion may be improved by using rehabilitation and biofeedback techniques. Of late, the rehabilitation of hyoid muscles with cervical flexion exercises has been shown to improve hyoid and laryngeal elevation, to increase UES aperture, to reduce pharyngeal residue, and to improve dysphagia symptoms in patients with neurogenic dysphagia (20). The management of patients with impaired UES aperture as a consequence of propulsive deficiencies should be basically oriented to increase bolus propulsion force and to rehabilitate the extrinsic mechanisms of UES aperture, particularly the activity of hyoid muscles (20).

5. Specific swallowing maneuvers. These are maneuvers the patient must be able to learn and perform in an automated way. Each maneuver is specifically directed to compensate specific biomechanical alterations (12, 21):

-Supraglottic (super/supraglottic) deglutition: its aim is to close the vocal folds before and during deglutition in order to protect the airway from aspiration. It is useful in patients with penetrations or aspirations during the pharyngeal stage or slow pharyngeal motor pattern.

-Stress or forced deglutition: its aim is to increase the posterior motion of the tongue base during deglutition in order to improve bolus propulsion. It is useful in patients with low bolus propulsion.

-Double deglutition: its aim is to minimize postswallow residue before a new inspiration. It is useful in patients with postswallow residue.

-Mendelsohn's maneuver: it allows for increased extent and duration of laryngeal elevation and therefore increased duration and amplitude of UES aperture.

6. Surgical/drug-based management of UES. Identifying an obstructive pattern at the UES allows patient management using a surgical cricopharyngeal section (17) or an injection of botulin toxin (19).

VF will help in treatment selection depending upon the severity of efficacy or safety impairment in each individual patient: a) patients with mild efficacy alterations and correct safety may have a family-supervised restriction-free diet; b) in patients with moderate alterations dietary changes will be introduced aiming at decreasing the volume and increasing the viscosity of the alimentary bolus; c) patients with severe alterations will require additional strategies based upon increased viscosity and the introduction of postural techniques, active maneuvers and oral sensorial enhancement; and d) there is a group of patients with alterations so severe that cannot be treated despite using rehabilitation techniques; in these patients VF allows to objectively demonstrate the inability of the oral route and the need to perform a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (27). Even though no absolute criteria exist, a number of teams tend to indicate gastrostomy in: a) patients with severe alterations of efficacy during the oral or pharyngeal stages, or with malnutrition; b) patients with safety alterations during the pharyngeal stage that do not respond to rehabilitation; and c) patients with significant silent aspirations, particularly in neurodegenerative conditions. For most patients requiring gastrostomy a small percentage of food may still be safely administered through the oral route.

CONCLUSIONS

The way to approach oropharyngeal dysphagia and its clinical relevance may be summarized in four points:

1. Oropharyneal dysphagia is a severe symptom with both nutritional and respiratory complications that are life-threatening.

2. It is a scarcely assessed and studied symptom in the clinical setting despite the availability of specific methods for its diagnosis, as is the case with videofluoroscopy and pharyngoesophageal manometry. Figure 1 summarizes a diagnostic algorithm for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia.

3. Therapeutic strategies exist for patients with oro-pharyngeal dysphagia, including changes in bolus volume and viscocity, postural changes, praxis, active maneuvers, rehabilitation procedures, and sensorial enhancement techniques, all of them of well-proven efficacy and capable of preventing complications. These techniques fail to treat some patients where gastrostomy must be indicated to prevent respiratory and nutritional complications.

4. The diagnosis and treatment of patients with oro-pharyngeal dysphagia depend on the work of a multidisciplinary team of professionals made up of physicians, nurses, language therapists, dieticians, and the patient's family.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Institut Guttmann: Dr. M. Bernabeu, Dr. S. Ramón, Dr. Orient (Brain Damage Unit), Mrs. M. Martinell (Language Therapist), Mr. P. Corpas (Radiodiagnosis).

Hospital de Mataró. Dr. P. Fossas, Dr. Palomeras (Neurology), Dr. M. Cabré (Geriatrics), Dr. M. Girvent (Surgery, nutritional studies), Mrs. M. Arús (Dietician), Mrs. R. Monteis (Geriatric Nurse), Mrs. E. Palomeras.

Fundació de Gastroenterlogía Dr. F. Vilardell. Mr. A. Blanco (Telecommunications Engineer), Mr. R. Farré, Mrs. Emma Martínez (in vitro viscosity studies).

Hospital de Sant Pau: Dr. J. Pradas, Dr. Rojas (Neurology Dept.), Dr. R. Güell, Dr. P. Antón (Pneumology Dept.), Mrs. M. Casanovas (Language Pathology School).

Fundació Dr. Vilardell. Mrs. G. Foyo.

Clinical trials prformed with the support of FIS 98/0794), Novartis Consumer Health S.A. (FCG/NHC-1), Fundació de Gastroenterología Dr. F. Vilardell, and Filial del Maresme de la Academia de Ciencies Mediques de Catalunya i Balears.

REFERENCES

1. Cook IJ, Kahrillas PJ. AGA Technical review on management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 455-78. [ Links ]

2. Dysphagia: a tertiary and specialised medical problem. www.dysphagiaonline.com. [ Links ]

3. Diagnosis and treatment of Swallowing Disorders in Acute-Care Stroke Patients. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Number 8, March 1999. Rockville, MD, USA. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/dysphsum.htm [ Links ]

4. Kerr JE, Bath PMW. Interventions for dysphagia in acute stroke (Protocol for a Cochrane Review. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 1999. [ Links ]

5. Disfagia Neurógena: Evaluación y tratamiento. Blocs 14. Fundació Institut Guttmann (ed. Badalona, 2002). www.guttmann.com [ Links ]

6. Buchholz DW. Neurogenic dysphagia: what is the cause when the cause is not obvious? Dysphagia 1994; 9: 245-55. [ Links ]

7. Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP, Johnston N, Whittaker S, Mendelson R, et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN 1987; 11: 8-13. [ Links ]

8. Wallace KL, Middleton S, Cook IJ. Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology 2000; 118: 678-87. [ Links ]

9. DePippo KL, Holas MA, Reding MJ. Validation of the 3-oz water swallow test for aspiration following stroke. Arch Neurol 1992; 49: 1259-61. [ Links ]

10. Clavé P. Protocolo de ensayo clínico: Evaluación videofluoroscópica del efecto terapéutico de resource espesante en pacientes con disfagia orofaríngea. FCG/Novartis-1, 2001. [ Links ]

11. Clavé P. Videofluoroscopic diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Nutrition Matters 2001; 3: 1-2. [ Links ]

12. Logemann JA. Manual for the videofluorographic study of swallowing. 2nd ed. Pro-ed, Austin, USA, 1993. [ Links ]

13. Clavé P. Diagnóstico de la disfagia neurógena: Exploraciones complementarias. En: Disfagia neurógena: evaluación y tratamiento. Blocs 14. Fundació Institut Guttmann (ed. Badalona). 2002. p. 19-27. [ Links ]

14. Kahrilas PJ, Logemann JA, Lin S, Ergun GA. Pharyngeal clearance during swallowing: a combined manometric and videofluoroscopic study. Gastroenterology 1992; 103: 128-36. [ Links ]

15. Fuster M, Negredo E, Cadafalch J, Domingo J, Illa I, Clavé P. HIV-associated polimyositis with life-threatening myocardial and esophageal involvement. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 1011-2. [ Links ]

16. Kahrilas PJ, Lin S, Rademaker A, Logemann JA. Impaired deglutitive airway protection: a videofluoroscopic analysis of severity and mechanism. Gastroenterology 1997; 113: 1457-64. [ Links ]

17. Shaw DW, Cook IJ, Jamieson GG, Gabb M, Simula MEW, Dent. Influence of surgery on deglutitive upper oesophageal sphincter mechanics in Zenker's diverticulum. Gut 1996; 38: 806-11. [ Links ]

18. Ali GN, Wallace KL, Schwartz R, deCarle J, Zagami AS, Cook IJ. Mechanisms of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia in patients with Parkinson's disease. Gastroenterology 1996; 110: 383-92. [ Links ]

19. Ravich WJ. Botulin toxin for UES dysfunction: Theraphy or poison? Editorial. Dysphagia 2001; 16: 168-70. [ Links ]

20. Shaker R, Easterling C, Kern M, Nitschke, Massey B, Daniels S, et al. Rehabilitation of swallowing by exercise in tube-fed patients with pharyngeal dysphagia secondary to abnormal UES openinng. Gastroenterology 2002. p. 1314-21. [ Links ]

21. Logemann JA. Dysphagia: Evaluation and Treatment. Folia Phoniatr Logop 1995; 47: 121-9. [ Links ]

22. Logemann JA, Kahrilas PJ, Kobara M, Vakil NB. The benefit of head rotation on pharyngoesophageal dysphagia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989; 70: 767-71. [ Links ]

23. Rasley A, Logemann JA, Kahrilas PJ, Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR, Dodds WJ. Prevention of barium aspiration during videofluoroscopic swallowing studies: value of change in posture. Am J Roentgenol 1993; 160: 1005-9. [ Links ]

24. Clavé P, Terré R, de Kraa M, Girvent, Farré R, Martínez E, et al. Therapeutic effect of increasing bolus viscosity in neurogenic dysphagia. ESPEN, 2003. [ Links ]

25. Clavé P, de Kraa M. Diagnóstico y tratamiento de la disfagia orofaríngea en el anciano. En: Sociedad española de Geriatría y Gerontología, y Sociedad Española de Nutrición Básica y Aplicada (eds). Manual de Práctica Clínica de Nutrición en Geriatría. Madrid, 2003. [ Links ]

26. Logemann JA, Pauloski BR, Colangelo L, Lazarus C, Fujiu M, Kahrilas P. Effects of a sour bolus on oropharyngeal swallowing measures in patients with neurogenic dysphagia. J Speech Hear Res 1995; 38: 556-63. [ Links ]

27. Mazzini L, Corrà T, Zaccala M, Mora G, Del Piano, M, Galante. Percutaneous endoscopic gasrostomy and enteral nutrition in amyotrophc lateral sclerosis. J Neurol 1995; 242: 695-8. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en