Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.96 no.8 Madrid ago. 2004

| RECOMENDATIONS ON CLINICAL NOTES |

Approaching focal liver lesions

F. Pons and J. M. Llovet

Liver Oncology. Service of Hepatology. IDIBAPS. Hospital Clínic. Barcelona. Spain

Pons F, Llovet JM. Approaching focal liver lesions. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 567-577.

Recibido: 08-01-03.

Aceptado: 12-01-04.

Correspondencia: Josep M. Llovet. Servicio de Hepatología. Institut d'Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS). Hospital Clínic. C/ Villarroel, 170. 08022 Barcelona. e-mail: jmllovet@clinic.ub.es

INTRODUCTION

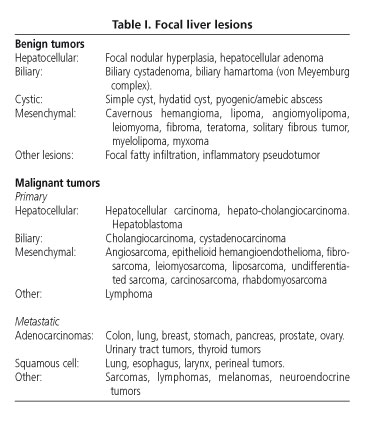

Focal liver lesions are defined as solid or liquid-containing masses foreign to the normal anatomy of the liver that may be told apart from the latter organ using imaging techniques. Their nature is widely varying, and may range from benign lesions with an indolent clinical course to aggressive malignant tumors (Table I). They are common findings as a result of the ever increasing use of imaging techniques in patients with nonspecific abdominal complaints (1).

The etiopathogenic diagnosis of focal liver lesions is based on clinical findings, laboratory data, imaging techniques, and frequently histology (1,2). Beforehand, incidental lesions in asymptomatic patients with no history of neoplasms or liver disease are usually benign, and cysts, hemangiomas and focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) are most prevalent in our setting (3). In contrast, liver lesions in cirrhotic patients demand that hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) be ruled out.

Initial assessment is relevant to exclude factors predisposing to selected tumors. Thus, a history of oral contraceptive use in a young woman suggests hepatocellular adenoma, cirrhosis is a preneoplastic condition for hepatocellular carcinoma, and sclerosing cholangitis predisposes to cholangiocarcinoma. Serologic tests for hepatitis viruses, Echinococcus and Entamoeba may suggest a diagnosis, as a number of tumor markers also do. However, a definite diagnosis is established using two essential tests: imaging techniques and a cytohistologic study.

Radiographic features provide a hint of a lesion' solid (benign or malignant tumors) or liquid (cysts, abscesses, etc.) contents. Solid tumor vascularization provides guidance on their etiology (3). Characteristically, tumors with arterial hypervascularization may be benign -adenomas or FNH- or malignant, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastases from neuroendocrine tumors or hypernephroma. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with vascular (gadolinium) or ferric (ferumoxides) contrast media have taken over radionuclide tests, and often allow getting around histology.

Sometimes, a pathologic study is absolutely necessary to assure a definite diagnosis. It is useful to establish the characteristics and origin of metastatic lesions, and to differentiate dysplastic lesions from hepatocellular carcinoma. Similarly, it may be essential to distinguish between liver adenoma and FNH, or to establish the nature of a number of atypical lesions. This practical clinical guide will review liver lesions most commonly seen in our setting, and a suggested diagnostic and therapeutic approach (Fig. 1) will be set forth.

CYSTIC LESIONS

Simple cyst

Simple liver cyst is a congenital lesion affecting 2-7% of the population (4-8). It is usually a single lesion of serous contents lined by cuboidal, biliary type epithelium with no communication with bile ducts (4-6). Regarding multiple lesions, liver or renal polycystosis stands out. This is a haphazard finding in asymptomatic patients, but may also induce pain when reaching greater sizes (diameter > 10 cm). It rarely causes jaundice, infection or hemorrhage (< 5%) (5,7). It is radiographically diagnosed, being depicted as an anechoic, wall-less, posterior enhanced lesion by ultrasonography (6,8) and as a T2-hyperintense, non-contrast-enhanced mass by MRI (5). If symptoms arise, it may be drained percutaneously. A simultaneous injection of an sclerosing substance such as alcohol or tetracycline is recommended, but relapse is common (6,7). In case of severe hemorrhage or recurrent infection a surgical approach is recommended (7).

Hydatid cyst

Liver hydatidosis is caused by the cestode Echinococcus granulosus. It is an endemic condition in Spain involving the liver, lung, and central nervous system among others (9,10). Hydatid cysts may become complicated in one third of cases, rupturing into the peritoneum or into the pleural space or bile tract. Using ultrasound, hydatid cysts may be differentiated from simple cysts by the presence of thicker walls, internal septa, daughter vesicles (multiloculated cysts), and hyperechogenic debris inside, as well as by the occasional presence of wall calcifications (9,10). CT or MRI may establish the diagnosis, assess complications, and define relations to vascular and biliary structures when planning a therapeutic approach. Serology is diagnostic in up to 70% of patients (10). Initial treatment with mebendazole or albendazole is recommended, as well as the use of either drug as an adjuvant to liver resection (10).

Hydatid cysts must be differentiated from biliary cystadenomas. The latter is a biliary, usually multiloculated tumor that mainly affects women and may degenerate to cystadenocarcinoma. Management is surgical.

Liver abscess

Pyogenic liver abscess is caused by gastrointestinal microorganisms as a result of cholangitis from bile obstruction (40% of patients) or portal bacteremia secondary to gastrointestinal infections such as diverticulitis or appendicitis (2,10,11). Clinical suspicion is based on the presence of general malaise, anorexia, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever and leukocytosis. CT allows diagnosis confirmation upon the finding of one or several cystic lesions with a hyperenhanced perilesional halo in the dynamic study, occasionally with gas inside (2,10,11). Blood culture is positive in 60% of cases (11). Treatment includes antibiotics and percutaneous or surgical drainage (10,11).

Pyogenic abscesses should be told apart from amebic

abscesses, which are rare in our setting and are caused by Entamoeba histolytica. Clinical manifestations are similar, but the latter type develops in patients with a history of traveling to countries with endemic amebiasis. Imaging techniques cannot differentiate between pyogenic and amebic abscesses but serology can, as tests are positive in 90% of patients. The treatment of choice is metronidazole, but drainage should be considered for refractory cases (12).

SOLID LESIONS

Liver hemangioma

Hemangioma is the commonest tumor in the liver, with a prevalence of 0.4-7.4% (2,4,13). Of vascular origin, this tumor consists of large vessels lined with mature endothelial cells within a fibrous stroma (2,4,5,14). It is a usually single small lesion of up to 20 cm in size that is more frequently found in women (1,2,4,13). In most cases, it is a haphazard finding in a patient with no symptoms or unspecific abdominal complaints (1,2,5,13). Of indolent natural history, it remains stable during follow-up but may grow in the presence of pregnancy or estrogenic therapies (1,2,13,14). It rarely causes symptoms and only exceptionally associates with thrombopenia, consumption coagulopathy and microangiopathic anemia (Kassabach-Merritt syndrome).

Diagnosis is radiographic. Ultrasonography shows a hyperechogenic, well-defined lesion that may be more heterogeneous in case of intratumor thrombosis (13,14). MRI is essential to tell atypical hemangioma from malignant tumors (2,13-15). Hemangioma is usually hyperintense in T2 and exhibits a characteristic pattern of contrast wash-in (early stages: reduced contrast enhancement or peripheral nodular enhancement; late stages: opacification extends towards the center) (4,5,14,15). Labeled red blood cell scintigraphy may be useful in atypical cases according to MRI for tumors > 2 cm (14,16). Management is symptomatic and surgery is only exceptionally considered (1,2,14).

Focal nodular hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is a benign tumor with a prevalence of 0.01% in the general population (2,4,5,17). It is usually smaller than 5 cm in size but may range from 1 to 20 cm, and is multiple in 20% of cases (4,5,17). It is considered a hyperplastic proliferation of normal liver cells in response to a preexisting arterial malformation (1,2,5,17). Histologically, it consists of liver cells abnormally laid out in sheets instead of lobules, which contain Kupffer cells and abnormal bile ducts not connected with the bile system. Greater lesions commonly have a central scar made up from fibrous stroma by a supply artery and hyperplastic bile ducts (5,17-19).

FNH is more frequent in women of childbearing age (2,5), develops in healthy livers, and is usually an incidental finding since its clinical course is commonly asymptomatic. It may exceptionally result in pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen (2). No cases with hemorrhage or malignization have ever been reported (1,2,17). Oral contraceptive use and pregnancy may favor its growth, but not its development (1,5,17). MRI is the technique of choice in the diagnosis of this condition, and has completely replaced liver scintigraphy. FNH is isointense in T1 and isointense or slightly hyperintense in T2, but central scars are clearly hyerintense (4,5,17,19). The lesion becomes hyperenhanced following gadolinium administration. Ferumoxide use may increase MRI' diagnostic yield (3).

In an asymptomatic patient with normal liver tests, a diagnosis of FNH may be reached by using MRI in 70% of cases (17,18). In the remaining patients, histology is required for a differential diagnosis regarding liver adenoma. FNH management is conservative. Oral contraceptive discontinuation is recommended, as this may decrease size (2).

Surgical resection is only advisable when diagnostic hesitancy exists.

Hepatocellular adenoma

Hepatocellular adenoma is an uncommon tumor (prevalence: 0.001%) that almost exclusively affects women of childbearing (2,5,17). It is associated with oral contraceptive use and less frequently with anabolic androgens and type I glycogenosis (2,4,5,17). Usually it occurs as a solitary mass, but a diagnosis of liver adenomatosis (10-20% of cases) should be considered for multiple adenomas (2,4,17,18). It is histologically made up of atypia-free liver cells arranged in rows separated by dilated sinusoids, with no portal spaces or bile ducts (2,5).

This tumor is asymptomatic in most cases, but may present with pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The most common complication is hemoperitoneum, whose risk increases for tumors larger than 5 cm and when contraceptive use persists beyond diagnosis (1,2,17,18). Similarly, cases with degeneration to liver cell carcinoma have been reported (1,4,17).

Diagnosing an adenoma may be difficult even when advanced imaging techniques and histology are used (17). In MRI scans it appears as a hyperintense mass in T2 -occasionally also in T1- with hyperenhancement during the arterial phase, whereas it is isointense/isodense versus the liver parenchyma in parenchymal phases (2,5,17,19). Kupffer cell scarcity is responsible for absent colloid uptake in liver scans using Tc99, a technique that has become obsolete for its differential diagnosis from FNH (1,2).

Whether symptomatic or otherwise, the management of hepatocellular adenoma is surgical in view of the risk of its peritoneal bleeding or malignant transformation (1,16,17). Patients with liver adenomatosis call for individualized decision making.

Liver metastatic disease

Liver metastases are the most common malignant tumors in the liver, since 35-40% of cancers develop this sort of dissemination (2,20). In our setting, most common metastases originate in the lung, the gastrointestinal tract (colon, stomach, pancreas, gallbladder), breast and ovary (21). The presence of metastatic liver disease usually entails a poor prognosis. Two major exceptions include colorectal cancer (CRC) metastases when susceptible of surgical resection, and neuroendocrine tumor metastases, as they are of a less aggressive nature.

A search for the primary tumor is warranted for patients with an acceptable general condition, be it in order to initiate an intent-to-heal surgical approach (CRC and neuroendocrine cancer) or to plan palliative management (21). From a clinical standpoint, a number of symptoms may provide guidance on the origin of the primary tumor: altered bowel habit and/or rectorrhage in CRC, jaundice in pancreatic tumors, carcinoid syndrome in endocrine tumors, etc. Tumor markers may be useful, but they are not definite parameters. CEA is increased in 90% of CRC metastases; in pancreatic and ovarian tumors CA 125 may be elevated; PSA may rise in prostate cancer, and 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid in carcinoid tumors (21). Regarding imaging techniques, CT reveals a hypovascular lesion with characteristic contrast uptake, whereas in a few cases there is hypervascular enhancement suggesting a carcinoid tumor, melanoma, sarcoma, hypernephroma or thyroid cancer (2,5). Octreotide scintigraphy may locate primary tumors and their extension in neuroendocrine metastatic disease (2).

For known primary tumors, biopsy is only needed when the nature of the liver lesion is doubtful (21). In contrast, for unknown primary tumors, fine-needle puncturing is a definite test in diagnosis guidance, its sensitivity and specificity being 85 and 93-100%, respectively (21).

A surgical management of metastatic liver disease may prolong survival for CRC, neuroendocrine tumors, and some renal tumors (2,21), but is controversial in the remaining tumors. In selected patients with CRC (less than 4 nodules), resection allows survivals of 40% at 5 years (21). For neuroendocrine tumors, resection may cure the disease when associated with primary tumor elimination (20). For non-resectable neuroendocrine tumors, hepatic embolization, interferon and somatostatin analogs may be useful in the management of carcinoid syndrome (21).

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequent primary tumor of the liver and the fifth more common malignancy worldwide, and represents the third cause of cancer-related mortality (22). In developed countries it sits on a cirrhotic liver in more than 80% of cases (23). Follow-up every 6 months using ultrasonography and alpha-fetoprotein determination is recommended in these patients to detect early tumors, at a time when healing treatments are feasible (24).

Diagnosis may be based upon histology or non-invasive criteria, only for cirrhotic patients. Non-invasive criteria include hypervascular tumors greater than 2 cm in size as confirmed by two imaging techniques, or by one imaging technique plus plasma alpha- fetoprotein more than 400 ng/mL (24). Ultrasonography usually reveals a hypo- or hetero-echogenic hypervascular lesion by using contrast media. CT scans show a hypodense lesion in baseline phases that takes up contrast during the arterial phase and then becomes hypovascular versus the liver parenchyma in portal and later phases (5,25). MRI reveals a lesion that is hypointense in T1 and

hyperintense in T2, with a behavior similar to that seen in CT in dynamic studies (5,19,25). Of late, angio-MRI has been shown to represent the best technique for tumor staging, mainly in the detection of nodules between 1 and 2 cm in size (25).

Differentiation between initial HCC and both regeneration and dysplastic nodules is important in patients with cirrhosis, as is also the case with atypical hemangioma and metastatic disease. In tumors greater than 2 cm, this may be achieved by using imaging techniques, whereas puncturing for histology samples is essential in tumors 1-2 cm in size (Fig. 2). The strategy recommended for nodules smaller than 1 cm is an expectant attitude and serial ultrasounds every 3 months (24).

The prognosis and treatment of HCC has been recently revised (26-28). Prognosis depends upon tumor stage, the grade of hepatocellular failure, general condition, and treatment used. We recently developed a new prognostic classification for HCC that takes these variables into account and allows selecting the best therapy possible for each patient (26-28). Patients with stage 0 disease have in situ carcinoma, and achieve 80% survivals at 5 years following healing treatment (29). Patients with early-stage disease (stage A) present with single tumors or 3 nodules less than 3 cm in size, are eligible for resection, liver transplantation or percutaneous treatment, and achieve 50-70% survivals at 5 years (26-28,30). Patients with multinodular asymptomatic tumors (stage B) are eligible for chemoembolization (31,32). Patients with symptomatic tumors or vascular, nodular or extrahepatic involvement (stage C) will receive new agents in clinical trials. Finally, end-stage patients (stage D) will receive symptomatic treatment.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is less common than ductal cholangiocarcinoma, and characteristically presents as a focal liver lesion (33). Histologically, it is an intrahepatic biliary epithelium-derived adenocarcinoma. Sclerosing cholangitis, liver clonorchiasis and choledocal cysts are conditions that predispose to ductal cholangicarcinoma (2,20,33), but their relation to the intrahepatic variety is not clear (33).

It most commonly develops in advanced-age individuals (65% of patients > 65 years) (2,20,34). It may be asymptomatic until a considerable size is reached; hence it presents with pain in the right hypochondrium and loss weight.

The diagnosis, prognosis and management of cholangiocarcinoma have been recently revised (23,34). Definitive diagnosis is based on histology. Baseline CT shows a hypodense lesion, hypovascular in dynamic studies (20), with peripheral contrast uptake during the portal phase (5). MRI reveals a tumor that is hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2 (5), which behaves as in CT during dynamic studies (5). A dilatation of the bile duct beyond the lesion may suggest this diagnosis (5). On occasion, it may result in an entrapment of vascular structures, but invasive thrombosis is rare (2,5,33).

Management is essentially surgical; with survival odds reaching up to 40-60% at 3 years (33). Liver transplantation has disparate results and is not recommended.

Although less frequent, angiosarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, primary lymphoma and primary neuroendocrine tumors should be considered in the differential diagnosis of primary malignant tumors of the liver.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

In the diagnostic strategy of liver masses, we may consider four clinical settings (21,35): a) liquid lesion; b) solid lesion in healthy patient; c) solid lesion in patient with liver disease; d) solid lesion in patient with suspected neoplasm (Fig. 1).

Strategy for liquid lesion

Ultrasonography suffices to determine the liquid contents of a focal liver lesion. Clinical characteristics, hydatid- and amebic-related serologic tests, and CT and MRI scans allow a differential diagnosis between simple cyst, liver and renal polycystosis, hydatid cyst, and pyogenic and amebic abscess. Telling apart a cystadenoma from a cystadenocarcinoma is difficult and requires the histological study of the resected lesion for confirmation. Finally, some metastases may look cystic, as is the case in those of ovarian or pancreatic origin, and in those stemming from selected neuroendocrine tumors.

Strategy for solid mass in healthy patient

The most prevalent lesion is hemangioma, which is diagnosed by using ultrasonography and MRI. FNH and adenoma should be ruled out in younger women or in women with a history of oral contraceptive use. FNH is asymptomatic and much more common. Despite the fact that MRI and to a lesser extent Tc99 scintigraphy may differentiate these two conditions in more than two thirds of patients (17,18), fine-needle aspiration is required for doubtful cases. If uncertainty persists on the nature of the lesion, surgical resection is recommended. Biopsy collection will also allow etiology to be established in asymptomatic malignancies and atypical tumors.

Strategy for focal lesion in cirrhotic patient

For these patients a diagnostic strategy has been clearly established by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) expert panel in their Barcelona-2000 EASL Conference (Fig. 2) (24). Lesions greater than 2 cm are usually diagnosed using imaging techniques; lesions of 1-2 cm in size require histology, and lesions less than 1 cm in diameter call for ultrasonographic surveillance at 3 months.

Strategy for focal lesion in patient with suspected metastasis or known tumor

Three distinct situations may be considered (21):

1. Patients with a known primary tumor who have liver metastases found at tumor staging or following his/her primary tumor management. Histology is only required when the nature of the focal lesion is doubtful.

2. Patients with an unknown primary tumor who are in good general condition. The search for a primary tumor is based on histology. Most common liver metastases stem from adenocarcinomas and poorly differentiated neoplasms:

-Adenocarcinoma (well or moderately differentiated): when of gastrointestinal origin, colorectal cancer must be ruled out particularly in patients older than 50 years with CEA > 5 ng/mL or altered bowel rhythm. Then gastric cancer must be excluded, and finally pancreatic cancer in patients with jaundice or altered CA-19.9 or CA-125. For non-gastrointestinal tumors, the following tumors should be ruled out in order of frequency: lung cancer and prostate cancer, the latter especially in patients with PSA > 4 ng/mL, increased acid phosphatase or bone osteoblastic metastases. In women, gynecologic tumors such as breast and ovary cancer.

-Poorly differentiated neoplasms: immunohistochemical techniques are of great clinical importance to differentiate carcinomas (anti-cytokeratin antibodies) from the rest of tumors. Amongst carcinomas, lung, breast, prostate, pancreas, and urologic cancers stand out. Neuroendocrine tumors make up a distinct subgroup according to their differential characteristics. Immunohistochemistry using chromogranin or neural enolase staining may confirm diagnosis. Among non-carcinomas, lymphomas, sarcomas and melanomas stand out.

3. Patients with an unknown primary tumor and severe impairment of the general condition (performance status

3-4). These patients exhibit severe toxic syndrome, liver infiltration and liver failure symptoms, severe laboratory abnormalities, and multiple metastatic images. Patient characteristics hamper a number of explorations and render therapy unuseful; symptomatic treatment is therefore recommended.

REFERENCES

1. Reddy KR, Schiff E. Approach to a liver mass. Seminars in liver disease 1993; 13: 423-35. [ Links ]

2. Rubin RA, Mithchell DG. Evaluation of the solid hepatic mass. Med Clin North Am 1996; 80: 907-28. [ Links ]

3. Ros PR, Davis GL. The incidental focal liver lesion: Photon, Proton, or Needle? Hepatology 1998; 27: 1183-90. [ Links ]

4. Horton KM, Bluemke DA, Hruban RH, et al. CT and MR imaging of benign hepatic and biliary tumors. Radiographics 1999; 19: 431-51. [ Links ]

5. Fulcher AS, Sterling RK. Hepatic Neoplasms. J Clin Gastroenteol 2002; 34: 463-71. [ Links ]

6. Benhamou JP, Menu Y. Enfermedades quísticas no parasitarias del hígado y del árbol biliar. En: Rodes, Benhamou, Bircher, eds. Tratado de Hepatología Clínica. 2ª ed. Masson, 2001. p. 911-3. [ Links ]

7. Zozaya JM, Rodríguez C, Aznarez R. Quistes hepáticos no parasitarios. En: Berenguer M, Bruguera M, García M, Rodrigo L, eds. Tratamiento de las enfermedades hepáticas y biliares. ELBA S.A., 2001. p. 333-41. [ Links ]

8. Kew MC. Hepatic tumors and cysts. En: Sleissenger, Fordtran, eds. Gastrointestinal and liver diseases. 7ª ed. Filadelfia: Saunders, 2002. p. 1577-602. [ Links ]

9. Breson-Hadni S, Miguet JP, Vuitton DA. Equinococosis hepática. En: Rodes, Benhamou, Bircher, eds. Tratado de Hepatología Clínica. 2ª ed. Masson, 2001. [ Links ]

10. Hidalgo M, Castillo MJ, Eymar JL. Hidatidosis hepática y abscesos hepáticos. En: Berenguer M, Bruguera M, García M, Rodrigo L, eds.. Tratamiento de las enfermedades hepáticas y biliares. ELBA s.a., 2001. p. 301-10. [ Links ]

11. Kibbler CC, Sánchez-Tapias JM. Infecciones bacterianas y Ricketsiosis. En: Rodes, Benhamou, Bircher, eds. Tratado de Hepatología Clínica. 2ª ed. Masson, 2001 [ Links ]

12. Martínez-Palomo. Infecciones protozoarias. En: Rodes, Benhamou, Bircher, eds. Tratado de Hepatología Clínica. 2ª ed. Masson, 2001 [ Links ]

13. Gandolfi L, Leo P Solmi L, et al. Natural history of hepatic haemangiomas: clinical and ultrasound study. Gut 1999; 32: 677-80. [ Links ]

14. Benhamou JP. Tumores hepáticos y biliares benignos. En: Rodes, Benhamou, Bircher, eds. Tratado de Hepatología Clínica. 2ª ed. Masson, 2001. p. 1671-7. [ Links ]

15. Mitchell DG, Saini S, Weinreb J, et al. Hepatic metastases and cavernous hemangiomas: distinction with standard and triple-dose gadoteridol-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 1994; 193: 49-57. [ Links ]

16. Weimann A, Burckhardt R, Klempnauer J, et al. Benign liver tumors: differential diagnosis and indications for surgery. World J Surg 1997; 21: 983-91. [ Links ]

17. Flejou JF, Menu Y, Benhamou JP. Tumores hepáticos y biliares benignos. En: Rodes, Benhamou, Bircher, eds. Tratado de Hepatología Clínica. 2ª ed. Masson, 2001. p. 1671-7 [ Links ]

18. Cherqui D, Rahmouni A, Charlotte F, et al. Management of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma in young women: a series of 41 patients with clinical, radiological and pathological correlations. Hepatology 1995; 22: 1764-81. [ Links ]

19. Hussain SM, Zondervan PE, Ifzermans JNM, et al. Benign versus malignant hepatic nodules: MR findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2002; 22: 1023-39. [ Links ]

20. Sherlock S , Dooley J. Hepatic Tumours. In: Sherlock S, Dooley J, eds. Diseases of the Liver and biliary system. 9th ed. Blackwell Science Publications, 1993. p. 518. [ Links ]

21. Llovet JM, Castells A, Bruix J. Tumores metastásicos. En: Rodes, Benhamou, Bircher, eds. Tratado de Hepatología Clínica. 2ª ed. Masson, 2001. [ Links ]

22. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: GLOBOCAN 2000. Int J Cancer 2001; 94: 153-6. [ Links ]

23. Colombo M. Risk groups and preventive strategies. In: Berr F, Bruix J, Hauss J,Wands J, Wittekind Ch, eds. Malignant liver tumors: basic concepts and clinical management. Kluwer Academic Publishers BV and Falk Foundation. Dordrecht, 2003. p. 67-74. [ Links ]

24. Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, et al. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL Conference. J Hepatol 2001; 35: 421-30. [ Links ]

25. Burrell M, Llovet JM, Ayuso MC, et al. MRI angiography is superior to helical CT for detection of HCC prior to liver transplantation: an explant correlation. Hepatology 2003; 38: 1034-42. [ Links ]

26. Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2003; 362: 1907-17-26. [ Links ]

27. Bruix J, Llovet JM. Prognostic prediction and treatment strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002; 35: 519-24. [ Links ]

28. Pons F, Llovet JM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: A clinical update. Med Gen Med 2003; 5 (3). [ Links ]

29. Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S. Natural history and prognosis od adenomatous hyperplasia and early hepatocellular carcinoma: multi-institutional analysis of 53 nodules followed up for more than 6 months and 141 patients with single early hepatocellular carcinoma treated by surgical resection or percutaneous ethanol injection. Jp J Clin Oncol 1998; 28: 604-8. [ Links ]

30. Arii S, Yamaoka Y, Futagawa S, et al. Results of surgical and nonsurgical treatment for small-sized hepatocellular carcinomas: A retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. Hepatology 2000; 32: 1224-9. [ Links ]

31. Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology 2003; 37: 429-42. [ Links ]

32. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte JJ, Ayuso C, Sala M, Muchart J, Solà R, Rodés J, Bruix J for the Barcelona-Clínic-Liver Cancer Group. Arterial embolization or chemoembolization vs symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable HCC: a randomized controlled trial. The Lancet 2002; 359: 1734-9. [ Links ]

33. Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma: Current concepts and insights. Hepatology, 2003; 37: 961-9. [ Links ]

34. Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin R, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: consensus document. Gut 2002; 51 (Supl. VI): vi1-9. [ Links ]

35. Xiol X. Estudio del nódulo hepático aislado. GH continuada, 2003; 2: 151-5. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en