Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.98 no.2 Madrid feb. 2006

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Diagnostic yield of 335 push video-enteroscopies

B. J. Gómez Rodríguez, C. Ortiz Moyano, R. Romero Castro, A. Caunedo Álvarez, M. D. Hernández Durán, P. Hergueta Delgado, F. Pellicer Bautista and J. Herrerías Gutiérrez

Service of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena. Sevilla, Spain

ABSTRACT

Background and objectives: the diagnostic yield of push enteroscopy (PE) varies widely from 13 to 78% of cases, according to the various series. The aim of this retrospective cohort study was to determine the endoscopic and histological yield of PE in our health area.

Patients and methods: a total of 355 consecutive patients (190 males/165 females; mean age 45 years, range 15-89) underwent PE over a 6-year period, from 1997 to 2003. PE was performed under sedation and without overtube. Small-bowel mucosa biopsies were taken in 199 explorations (56%). Clinical indications for PE included: chronic diarrhea (35%), occult digestive bleeding (ODB) or iron-deficiency anemia (28%), suspected small-bowel malignancy (16%), chronic abdominal pain (28/355; 8%), follow-up of polyposis or malabsorption syndromes (7%), and abnormal radiographic findings (6%).

Results: PE detected lesions in 122 cases (34%); in 6 cases (6%) lesions were within the reach of esophagogastroduodenoscopy. A normal macroscopic appearance of the small intestinal mucosa with an abnormal histological study was seen in 16 patients (6%). Major findings included: malabsorptive diseases (14%), nonspecific enteropathy (5%), angiodysplasia (3,5%), lymphangiectasia (3%); jejunal polyps (2%), Crohn's disease (2%), intestinal tumors (2%), extrinsic jejunal strictures (0.5%), and other (10/355; 3%). Abnormal radiographic findings (62%), chronic diarrhea (37%) and ODB (31%) were the indications with a higher diagnostic yield. No major complications were seen.

Conclusions: according to our experience, PE is a safe and useful tool for the evaluation of small-bowel disease, especially in some indications (abnormal radiographic findings, chronic diarrhea, and ODB). Small-bowel biopsy increases PE's diagnostic yield in patients with chronic diarrhea.

Key words: Push-enteroscopy. Occult GI bleeding. Malabsorption. Intestinal biopsy. Diagnostic yield.

Gómez Rodríguez BJ, Ortiz Moyano C, Romero Castro R, Caunedo Álvarez A, Hernández Durán MD, Hergueta Delgado P, Pellicer Bautista F, Herrerías Gutiérrez J. Diagnostic yield f 335 push video-enteroscopies. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2006; 98: 82-92.

Introduction

The difficulty of exploring the small bowel is due to its length and anatomic peculiarities, resulting not only in various incomplete examinations but also in the interpretation of observed lesions. With the development of new diagnostic tools such as capsule endoscopy (CE) some of these difficulties have been overcome, and now the entire small bowel can be viewed and hence the so called "occult zone" has disappeared. However, in some specific situations, traditional enteroscopy is necessary.

Nowadays the role of push enteroscopy is well established, especially in cases such as occult digestive bleeding (ODB), abnormal radiographic findings, chronic diarrhea, and malabsorption, but also in the screening of small-bowel polyposis, the staging of inflammatory intestinal disease, and in nonspecific chronic abdominal pain.

In addition, PE does have numerous therapeutic possibilities including treatment of digestive bleeding, polypectomy, dilation of intestinal stenosis, removal of foreign material, treatment of intestinal invaginations, and placement of enteral feeding tubes and prostheses. PE also allows an improvement of radiological techniques almost forgotten, such as small-bowel follow-through and intraoperative enteroscopy.

However, there is no consensus in the studies published regarding the diagnostic yield of PE. Differences in results may be due to the wide variety of indications this technique has (1). In our series, the largest to this day, the diagnostic yield of PE has been evaluated according to the most frequent indications in our health-area.

Patients and method

Between 1997 and 2003, 355 PE were performed consecutively. All patients were identified and their informed consent was obtained for the examination. The majority of patients were referred by gastroenterologists belonging to our health area. All patients had at least undergone a prior esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy. Patients with malabsorption or polyposis in which a PE had been performed prior to the inclusion period were excluded from this study.

Clinical indications for PE included: a) evaluation of chronic diarrhea, especially if malabsorption was suspected, mostly celiac disease; b) occult digestive bleeding or iron-deficiency anemia; c) screening for lesions in patients with symptoms or laboratory values suggestive of malignancy (weight loss, anorexia, asthenia, change in stool habits, elevated tumor markers); d) unspecific chronic abdominal pain; e) follow-up of patients with polyposis and malabsorption syndromes; and f) abnormal radiological findings (stenosis or filling defects in a small-bowel follow-through).

The examination was performed under sedation, which was administered by the endoscopist using midazolam or diazepam and meperidin intravenously according to the patient's weight and age. All examinations were performed using 2 enteroscopes: a Pentax VSB 2900 (length: 240 cm, diameter: 9.8 mm, working channel: 2.8 mm, vision angle: 100º), and a Fuji EN-200WM (length: 230 cm, diameter: 10.5 mm, working channel: 2.8 mm, vision angle: 140º). No overtube was used in any examination. The progression of the enteroscope was achieved using introduction and withdrawal maneuvers, compression, and postural changes by the patient. The distance of insertion in the jejunum was estimated by subtracting 60 cm, the medium distance between the teeth and pylorus, from the distance reached by the enteroscope inserted as far as possible, and then rectifying until the tip of the enteroscope started withdrawing.

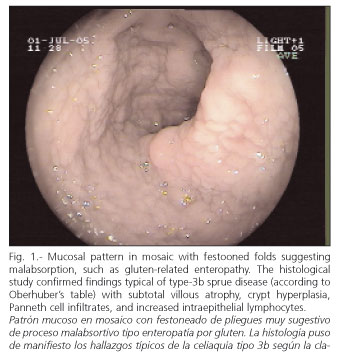

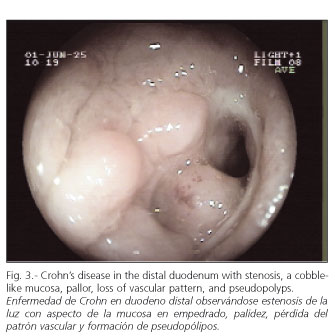

PE was carried out by six senior endoscopists in our Hospital, who took photographs and reached a consensus on the final diagnosis. Various endoscopic patterns were defined: a) malabsorption pattern suggesting celiac disease (Fig. 1): atrophic mucosa, granular and mosaic-shaped with festoon-like intestinal folds; b) unspecific enteropathy: patched erythematous or diffuse tip, without erosions or ulcerations; c) lymphangiectasia (Fig. 2): flat plaques or whitish tip with or without milky white exudates; d) Crohn's disease (Fig. 3): cobbled mucosal pattern, geographical or serpinginous ulcerations, aphthas, pseudo-polyps, stenosis of intestinal lumen; e) angiodysplasia: cherry-colored vascular balls; f) malignant tumors (Fig. 4): exophytic protrusions or areas of infiltration on the intestinal wall; g) polyps (Fig. 5): circumscribed mucosal protrusions; and h) intestinal stenosis, when a reduction of the lumen did not allow the endoscope to go through (Fig. 6).

The findings in the esophagus, stomach and proximal duodenum were considered lesions within the reach of a conventional esophageal gastroduodenoscope, and were therefore not included in the study.

The exploration was considered complete when the insertion was done with a minimal twisting of the enteroscope in the stomach, which allowed the endoscopist to explore the mucosa in withdrawal. The time needed for each exploration was not registered. Biopsies were taken only when the endoscopist considered these to be necessary for the diagnosis. When a therapeutic endoscopy was necessary, it was carried out with the injection of sclerosing agents or adrenaline, argon-plasma, polypectomy loops (Fig. 5), and hydrostatic balloon in case of dilation.

Student's t-test was used for quantitative variables, and Chi square for qualitative variables; a p < 0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic data

In all, 54% (190) of the 355 patients were males, and 46% (165) were females. Mean age was 45 years (range: 13 to 84 years). Major indications for PE in the youngest patients included chronic abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, malabsorption and follow-up of malabsorption syndromes, and polyposis with a mean age of 37, 34 and 33 years, respectively. Major indications for PE in the elder patients were ODB, abnormal radiographic findings, and lesions suspicious of malignancy with a mean age of 58, 53 and 49 years, respectively (p = 0.01).

Regarding sex, main indications in men included chronic abdominal pain (75%) and abnormal radiographic findings (66%). No difference in sex was found when the indication was chronic diarrhea-malabsorption and ODB. The ratio of females was higher when the indication was lesions suspicious of malignancy (52%) and follow-up of malabsorption syndromes and polyposis (60%). However, these differences in sex were not statistically significant (p = 0.32).

Indications

The most frequent indication for PE in our series was chronic diarrhea in 35% (126 out of 355), followed by occult GI bleeding and iron-deficiency anemia in 28% (99 out of 355), and suspected malignant tumor in 26% of cases (56 out of 355). The remaining indications were chronic abdominal pain (8%), follow-up of malabsorption syndromes and polyposis (7%), and abnormal radiographic findings (6%).

Diagnostic yield

We found endoscopic lesions in 121 of 355 PEs, which represents a diagnostic yield of 34%. Six percent of these lesions were located within the reach of esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Endoscopic findings included 50 (14%) lesions suggesting malabsorption, 19 (5%) unspecified enteropathies, 13 (3.5%) angiodysplasias, 10 (3%) lymphangiectasias, 10 (3%) miscellaneous (including jejunal diverticulosis, jejunal ulcerations secondary to NSAID intake, and intestinal varicosis among others), 6 (2%) duodenal Crohn's disease, 6 (2%) benign and malignant intestinal tumors, 6 (2%) jejunal polyps, and 2 (0.5%) jejunal stenoses (Table I). All diagnoses were histologically confirmed. Indications with the highest sensitivity were abnormal radiographic findings and suspicion of malabsorption syndrome (Table II).

Biopsies were taken in 199 patients (56% of all patients). There were no endoscopic lesions in 66% (234) of patients; however, we found that even without endoscopic lesions, the histological study was abnormal in 6% of them. In the study of chronic diarrhea, in 75 cases there were no endoscopic lesions, and 14 had an abnormal histological study, 13 with villous atrophy and one lymphoid nodular hyperplasia, which increased diagnostic efficiency from 40 to 51%. Two of the 17 explorations for patient follow-up with already known normal profiles showed an abnormal histology, one villous atrophy and a non-Hodgkin lymphoma in a patient monitored for celiac disease.

An endoscopic exploration of the proximal jejunum was achieved in 295 patients. The mean distance of insertion beyond Treitz's angle was 63 ± 4 cm, although the length of insertion was not checked with radiology and therefore limits the validity of measurements.

During the study there were no major complications; one patient showed a self-limited vagal reaction; another patient developed a hematoma in the pharynx after the exploration, which resolved spontaneously, and yet another patient with ischemic cardiopathy had an angina, which resolved with the use of a sublingual nitrite tablet. None of them needed intervention outside the endoscopic room.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to evaluate the diagnostic yield of PE in a large patient group according to indication. The diagnostic yield of PE has been, and still is, a subject of debate in this decade (2-4). In our series, the indication with the highest diagnostic yield was the presence of abnormal radiological findings, which represented 62% of patients. This is in agreement with previously reported studies (5,6). It should be mentioned that 2 of these patients (0.05%) were diagnosed with jejunal adenocarcinoma. These data, while scarce, support the role of PE in the evaluation of these patients.

In our study, chronic diarrhea represented the second indication with the highest diagnostic yield. Although most patients suffered from sprue, patients with Crohn's disease and other malabsorption syndromes were included. Diagnostic yield in our cases was 40%, which is remarkable regarding other studies (7-9). A possible explanation could be that most of these patients had sprue. One could argue that, if such is the case, the diagnosis of sprue may be reached by duodenal biopsy with no need for PE. However, as lesions may develop in the jejunum or be patchy (10), we do recommend enteroscopy, just as PE is mandatory in refractory sprue, in order to exclude malignancy (11) and in cases unresponsive to a gluten free diet (12). Also, a normal PE does not exclude the presence of sprue as, in fact, in up to 11% of normal mucosas, as confirmed by endoscopy, there is villous atrophy (13). We found 51 patients with this indication (51 out of 126). We collected biopsy samples in 75 of all normal PEs. The histological study showed 13 villous atrophy cases and 1 lymphoid nodular hyperplasia, which confirms the important role of PE in this indication. The histological study increased the diagnostic yield from 32 to 40% in the subgroup of patients followed up for malabsorption. In addition, a case of villous atrophy was diagnosed, as was another of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in a patient that had not been previously diagnosed with sprue. The latter supports the role of PE in this indication, as we have already mentioned (8).

Besides, it must be said that in our Department, and according to our protocol, we normally perform a PE exam in cases of chronic diarrhea when conventional endoscopic and radiological techniques have not been conclusive. This may explain the fact that this is the most frequent indication in this study, and because of its lower diagnostic efficacy it may have limited the global yield of the complete study.

As for polyposis, PE is a safe and reliable method to find and treat patients with adenomatous polyposis and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. The polypectomy technique allows obstruction reductions in these patients, and therefore avoids urgent surgery (14).

Capsule endoscopy has been shown to give better results than PE in cases of chronic gastrointestinal bleeding (15,16). However, ODB still remains the main indication for PE, with a diagnostic yield of 35-70% (17). Since 2-10% of chronic bleedings are located in the small intestine (18), PE can indicate not only the bleeding lesion but also its location and bleeding severity. It also allows therapeutic endoscopy with a success rate of 85% (19). Nevertheless, the diagnostic yield of PE should be revised, taking into account the number of lesions that can be reached with conventional endoscopy (20). In other studies, lesions reached with EGD varied between 20 and 67% (21,22). In a recent study, Mylonaki et al. (23) showed that the lesions that more often remain unseen are Cameron erosions in giant hiatal hernia, peptic ulcers, Dieulafoy ulcers, and watermelon stomachs. Likewise, it has been described that lesions missed with colonoscopy are mostly polyps and neoplasms (24). In our study, the diagnostic yield for anemia likely due to digestive hemorrhage was 31%, of which arterio-venous malformation (AVM) was the most frequent cause, followed by intestinal tumors. AVMs are more frequent in patients over 50, while intestinal tumors appear in younger patients (25). Therapeutic techniques were used on these lesions and, as described earlier (19), these required more than one session. The results of our study seem to confirm that PE still has a role in the study of these patients in spite of the recent emergence of capsule endoscopy (26,27).

We shall finally mention the last indication we have studied in our series -chronic abdominal pain. As previously stated, this indication showed a poor diagnostic yield of 18% (5 out of 28), in agreement with what has already been published (2). This result may be due to the low number of patients with this indication.

We use no overtube in our explorations because, in our experience, it may be painful for the patient and result in iatrogenic lesions (Mallory-Weiss lacerations, acute pancreatitis, pharyngeal lesions); this may have limited depth of insertion for the enteroscope in our study. There is no uniformity in the literature today regarding the usefulness of overtubes in PE. Although its use may be a significant improvement for length of insertion and prevents curls in the stomach (28), percentage of pathologic findings is not significantly important (29). A recent study by May et al. (30) shows a new method to perform PE using an enteroscope with a double balloon, which allows to visualize the whole of the small intestine by oral and anal introduction. The use of enteroscopes with variable stiffness also seems to show promising results (31,32).

Conclusions

Our conclusion is that PE is a useful technique to study diarrhea and malabsorption cases and their follow-up, to study radiological abnormalities, and in the evaluation of obscure bleeding hemorrhages. It has also been shown to be a safe technique. Biopsies in patients with chronic diarrhea and malabsorption, as well as their follow up, have shown its benefit and increased the sensitivity of the technique, thus justifying the routine performance of biopsies in all patients undergoing this exploration.

References

1. Lin S, Branch MS, Shetzline M. The importance of indication in the diagnostic value of push enteroscopy. Endoscopy 2003; 35: 315-21. [ Links ]

2. Sharma BC, Bashin DK, Makharia G, et al. Diagnostic value of push-type enteroscopy: a report from India. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 137-40. [ Links ]

3. Linder J, Cheruvattath R, Truss C, Wilcox C. Diagnostic yield and clinical implications of push enteroscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002; 35: 383-6. [ Links ]

4. Chen RY, Taylor AC, Desmond PV. Push enteroscopy: a single centre experience and review of published series. ANZ J Surg 2002; 72: 215-8. [ Links ]

5. Landi B, Tkoub M, Gaudric M, et al. Diagnostic yield of push-type enteroscopy in relation to indicatio. Gut 1998; 42: 231-5. [ Links ]

6. Forouzandeh B, Wright R. Diagnostic yield of push-type enteroscopy in relation to indication. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48: 645-7. [ Links ]

7. Penazzio M, Arrigoni A, Risio M, Rossini PF. Clinical evaluation of push enteroscopy. Endoscopy 1995; 27: 164-70. [ Links ]

8. Cellier C, Cuilleier E, Patey-Mariaud de Serre N, Marteau P, Verkarre V, Briere J, et al. Push enteroscopy in celiac sprue and refractory sprue. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 50: 613-7. [ Links ]

9. Cuillerier E, Landi B, Cellier C. Is push enterosocpy useful in patients with malabsorption of unclear origin? Am J Gastroentrol 2001; 96: 2103-6. [ Links ]

10. Barkin JS, Schonfeld W, Thomsen S, et al. Enteroscopy and small bowel biopsy. An improved technique for the diagnosis of small bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 1985; 31: 215-7. [ Links ]

11. Gay GJ, Delmotte JS. Enteroscopy in small intestinal inflammatory diseases. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 1999; 9: 115-23. [ Links ]

12. Parry SD, Welfare MR, Cobden I, Barton JR. Push enteroscopy in a UK district general hospital: experience of 51 cases over 2 years. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 14: 305-9. [ Links ]

13. Murray JA, Smith JA, Cupland K. Intestinal disaccharidase defficiency without villous atrophy may represent early celiac disease. Scan J Gastroenterol 2001; 36: 162-8. [ Links ]

14. Penazzio M, Ronini FP. Small bowel polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: management by combined PE and intraoperative enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 304-8. [ Links ]

15. Ell C, Remke S, May A, et al. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 2002; 34: 685-9. [ Links ]

16. Saurin JC, Delvaux M, Gaudin JL, et al. Diagnostic value of endoscopic capsule in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: blinded comparison with video PE. Endoscopy 2003; 35: 576-84. [ Links ]

17. Zuckerman GR, Prakesh C, Askin MP, et al. AGA technical review on the evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology 2000; 118: 201-21. [ Links ]

18. Lingenfelser T, EllC. Lower intestinal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 15: 135-53. [ Links ]

19. Hayat M, Axon AT, O'Mahony S. Diagnostic yield and effect on clinical outcomes of push enteroscopy in suspected small-bowel bleeding. Endoscopy 2000; 32: 369-72. [ Links ]

20. Descamps C, Schmit A, Van Gossum A. "Missed" upper gastrointestinal tract lesions may explain "occult" bleeding. Endoscopy 1999; 31: 452-5. [ Links ]

21. Banai J, Szanto I. Push enteroscopy in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown origin. Magy Seb 2001; 54: 155-7. [ Links ]

22. Soderman C, Uribe A. Enteroscopy as a tool for diagnosing gastrointestinal bleeding requiring blood transfusión. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2001; 11: 97-102. [ Links ]

23. Mylonaki M, Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy: a comparison with push enterosocpy in patients with gastroscopy and colonoscopy negative gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut 2003; 52: 1122-6. [ Links ]

24. Haseman JH, Lemmel GT, Rahmani EY, et al. Failure of colonoscopy to detect colorectal cancer: evaluation of 47 cases in 20 hospitals. Gastrointest Endosc 1997; 45: 451-5. [ Links ]

25. Van Gossum A. Obscure digestive bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 15: 155-74. [ Links ]

26. Douard R, Wind P, Paris Y, et al. Intraoperative enteroscopy for diagnosis and management of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Surg 2000; 180: 181-4. [ Links ]

27. Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: results of the italian multicentre experience. First Given conference capsule endoscopy, Rome, 2002, p. 17-9. [ Links ]

28. Taylor ACF, Chen RYM, Desmond PV. Use of an overtube for enteroscopy- Does it increase depth of insertion? A prospective study of enteroscopy with and without an overtube. Endoscopy 2001; 33: 227-30. [ Links ]

29. Benz C, Jakobs R, Riemann JF. Do we need the overtube for PE? Endoscopy 2001; 33: 658-61. [ Links ]

30. May A, Nachbar L, Wardak A, et al. Double-balloon enteroscopy: preliminary experience in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or chronic abdominal pain. Endoscopy 2003; 35: 985-91. [ Links ]

31. Harewood GC, Gostout CJ, Farrell MA, et al. Prospective controlled assesment of variable stiffness enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 58: 267-71 [ Links ]

32. Keizman D, Brill S, Umansky M, et al. Diagnostic yield of routine push enteroscopy with a graded-stiffness enteroscope without overtube. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 57: 877-81. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondencia:

Correspondencia:

B.J. Gómez Rodríguez.

Servicio de Aparato Digestivo.

Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena.

Avda. Doctor Fedriani, 3.

41009 Sevilla.

Fax: 955 008 805.

e-mail: bgomezr@medynet.com - cortizm@supercable.es

Recibido: 18-11-04.

Aceptado: 04-10-05.

texto en

texto en