Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.98 no.6 Madrid jun. 2006

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Current epidemiology and accessibility to diet compliance in adult celiac disease

Epidemiología actual y accesibilidad al seguimiento de la dieta de la enfermedad celiaca del adulto

F. Casellas, J. López Vivancos1 and J. R. Malagelada

Service of Digestive Diseases. University Hospital "Vall d'Hebron".

1Service of Internal Medicine. Hospital General de Catalunya. Barcelona, Spain

ABSTRACT

Background: the widespread of serologic diagnosis for celiac disease has brought about an epidemiologic shift. Little up-to-date information is available on relevant epidemiologic issues regarding diagnosis, information, and therapy.

Objective: to examine forms of presentation, diagnostic difficulties, follow-up, information sources, and treatment-related issues regarding celiac disease.

Method: a cross-sectional observational study using a self-completed questionnaire.

Results: seventy-three adult patients were included; 15.0% of cases were diagnosed over 60 years of age. Most were non-smokers (91.8%). The rate of first-degree relatives with celiac sprue was 10.9%. The disease had a classic presentation in only 54.7% of cases. A functional gastrointestinal disorder was initially suspected in 42.4% of patients. Diet adherence is adequate, with unintentional lack of compliance in 15.5% of patients. Diet results in absent or improved symptoms in virtually all patients, but most of them consider compliance a challenge. Forty percent had difficulty finding gluten-free food, and 50.8% had problems in labelling recognition.

Conclusions: celiac disease presents at any age, has a great variety of manifestations, and responds very well to gluten-free diet. It is crucial that patients be highly motivated and informed, and that they know for certain which foods and manufactured products are to be to used. Therefore, adequate control will result from coordination and cooperation regarding all resources involved, including medical care, and information provided by associations and other sources such as the Web.

Key words: Celiac disease. Celiac sprue. Patient opinion. Clinic. Treatment. Gluten-free diet. Epidemiology.

Introduction

Celiac disease is a chronic enteropathy of autoimmune origin that is triggered by a permanent intolerance to selected gluten peptides in a number of cereals, develops in genetically predisposed individuals, and disappears upon gluten exposure discontinuation. A characteristic of celiac disease is the development of antibodies against both self (reticulin, transglutaminase, etc.) and foreign (gliadin, etc.) antigens (1). The high diagnostic yield attained by the positivization of such antibodies allowed the recognition of innaparent, atypical forms of celiac disease, which has led to a fundamental shift in the epidemiology of this disease. Thus, when celiac disease diagnosis was primary based on clinical data, the average prevalence of this condition was 1/3,345 worldwide, whereas its mean prevalence has increased to 1/266 around the world following the incorporation of serology into the diagnostic process (2). The prevalence of celiac disease in Spain's adult general population is also very high -1/389 inhabitants (3).

The natural interest arisen by a disease as common as celiac disease in our setting has encouraged reports on clinical studies that have outlined both the clinical and biologic manifestations of this condition (4,5). Our considerable knowledge of clinical manifestations in celiac sprue is in contrast with the sparse information available on other equally relevant aspects of this disease, as are diagnostic difficulties that may result in diagnostic errors and delays, challenges in follow-up, lost work days, extent and quality of information on the disease, etc.

Similar to its well-structured diagnosis, therapy for this condition is also well established, and a complete, definitive exclusion of gluten-containing foods is recommended (6). However, we lack in our setting contrasted information regarding patient opinions on the difficulty entailed by diet adherence, compliance extent, response to therapy, etc. In this respect, a range of factors has been identified in England -partaking in celiac patient associations, understanding labelling, easy access to gluten-free foods, having information available, and diet compliance control, all of which are associated with good gluten-free diet compliance (7). However, we have no information on the factors associated with adequate gluten-free diet adherence in our setting.

The need for information on reasons leading patients to look for medical help, diagnostic delay, follow-up after diagnosis, information sources, and treatment-related issues in our setting has encouraged the performance of this study. A cross-sectional observational study has been undertaken by means of a specifically-designed questionnaire, which has been administered to a heterogeneous group of celiac patients.

Methods

Patients

Patients older than 20 years with celiac disease, diagnosed using serology and jejunal biopsy histology on samples obtained with Watson's capsule according to current criteria (8), and followed from April 1, 2004 to May 31, 2005 were included. Both patients already on a gluten-free diet and newly diagnosed subjetcs who still were not on a gluten-free diet were included.

Procedure

Patients included in the study completed a 20-item questionnaire regarding demographic data (age, gender, place of residency, family status, education, occupational status), clinical data (symptoms for which they sought help, initial diagnosis, time with symptoms before diagnosis), medical control (monitoring person, how symptoms have changed), information on the disease (how is it obtained, opinion on information), and gluten-free diet-related issues (information, access, opinion on food labelling, response to gluten-containing meals, etc.). Questions related to disease follow-up and treatment were only answered by patients already diagnosed and on a gluten-free diet.

Gluten-free diet compliance in already diagnosed, treated individuals was established by adapting the self-administered questionnaire by Morisky et al. (9). The original questionnaire has 4 items regarding treatment compliance that are answered using a binary (yes/no) scale. The first two questions explore unintentional non-compliance (sometimes I forget about my diet / sometimes I neglect my diet), and the last two questions refer to intentional non-compliance (when I feel well I sometimes discontinue my diet / if I don't feel well I sometimes discontinue my diet). If question 3 or 4 is responded in the affirmative, the patient is considered to voluntarily interrupt his or her diet. If question 1 or 2 is answered in the affirmative, the patient is considered to involuntarily interrupt his or her diet, either from neglect or forgetfulness. This questionnaire was originally designed for use in the monitoring of drug compliance, and has therefore been adapted buy substituting gluten-free diet for drugs. Similar to previous studies, and given that many patients report that "they never forget about their diet", a fifth option was added where the response "I never forget about my diet" is considered a marker of good diet adherence (10).

Statistics

Results are expressed as medians and 25-75 percentiles. The presence of statistical differences was calculated using a Mann-Whitney univariate analysis for non-parametric variables or Fisher's exact test, when needed. The Kruskal-Wallis range variance test was used for multivariate analyses.

Results

Patients

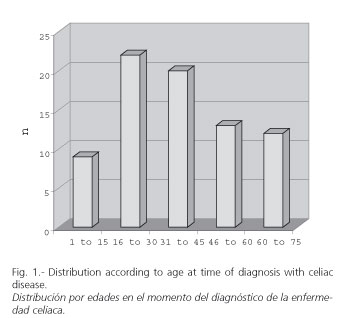

Seventy-three patients were included. Of these, 62 are in the group of previously identified patients on a gluten-free diet, and 11 are in the newly diagnosed group, not on a gluten-free diet yet at the time of inclusion. Demographic characteristics of patients at the time of inclusion are listed in table I. Young females predominate (22 patients were 20 to 30 years old, and 21 patients were 30 to 40 years old at the time of inclusion). However, their distribution according to age at the time of diagnosis (Fig. 1) shows that this disease develops both during childhood (10.9% of patients were diagnosed before 15 years of age) and late life (15.0% were diagnosed from 60 years of age onwards).

Other notable aspects of patients in the study include the fact that most were non-smokers, came from an urban setting (most from the city and outskirts of Barcelona), were married, had secondary or university-level education, and had a job. While statistical comparisons cannot be made, the low number of smokers (8.2%) among patients included in the study is most striking when compared to figures reported by the last National Health Survey above 16 years of age, which estimates 39.1% for males and 24.6% for females (11).

Eight patients reported having first-degree relatives with celiac disease, which gave a celiac disease rate among relatives of 10.9%, similar to that reported by other previous national series (12,13).

Characteristics of celiac disease

Table II lists the primary characteristics of this disease. At the time of inclusion, 49 patients on a gluten-free diet reported no symptoms (81.0%), whereas 9 out of 11 in the group still without treatment had symptoms (81.8%). Symptoms most commonly reported at the time of inclusion were diarrhea in 12 patients, asthenia or fatigue in 7, weight loss in 5, abdominal pain in 3, and abdominal distension in 2. Time from diagnosis to inclusion was 44.0 [9.0-114.0] months for previously diagnosed patients.

Celiac disease presented in its classic form (chronic malabsorptive diarrhea) in 40 (54.7%) patients. Other forms of presentation of celiac disease included ferropenic anemia in 19 patients (26.0%), vitamin B12 deficiency in 3 (4.1%), hypertransaminasemia in 4 (5.4%), mucocutaneous lesions resembling herpetiform dermatitis or recurrent oral aphtas in 6 (8.2%), and isolated cases of thyroid disease, primary IgA immunodeficiency, and lactose intolerance. No initially asymptomatic patient was included who had been identified by a screening program for patient relatives.

The presence of conditions associated with celiac sprue at inclusion was detected in 22 patients. Conditions most commonly associated included thyroid diseases in 8 cases, IgA immunodeficiency in 4, scleroderma in 2, and isolated cases of lymphoma, inflammatory myopathy, depression, Crohn's disease, nephrotic syndrome, Raynaud's disease, Sjögren's disease, and cerebellar atrophy.

Symptoms or complaints prompting patients to seek help were diverse, and are listed in table III. It should be noted that most symptoms are gastrointestinal (diarrhea is most common) and usually multiple (67.1% of patients reported having consulted for more than one symptom). Median duration for these symptoms prior to the diagnosis with celiac disease was 12 months for all 61 patients where said period of time could be established. For 71 patients -and according to their opinion- the cause to which presentation symptoms were initially attributed could be established. In 26 cases (36.6%) the initial diagnosis was already that of celiac disease. In 30 cases (42.2%) symptoms were related to functional disorders such as "nervousness" (19 patients) or irritable bowel syndrome (11 patients). In 10 cases (13.6%) initial symptoms were attributed to some sort of food intolerance, such as lactose intolerance. In the remaining 5 cases other diagnoses were initially reached, but these could not be specified at the time of inclusion.

Issues relating to monitoring and follow-up

Probably as a consequence of their origin, all patients included in the study are monitored by specialists, most of them hospital physicians (95.7 vs. 4.3% in outpatient clinics). Of all 64 patients who answered the question "¿How many work days do you usually lose in a year because of disease follow-up?", 44 (68.7%) responded that they lost no work days at all. Most patients reporting work day losses because of disease follow-up refer to one or two days (11 patients, 17.2%); however, three patients (4.6%) needed two weeks a year, and loss of work days in a year according to patient views amounts thus to 2 [1.5-6.0] days.

All patients were asked about their information sources regarding celiac disease, and how they rated such information. Results, listed in table IV, were differentiated for patients already diagnosed with celiac disease at inclusion and patients being diagnosed at that time. Three facts are noticeable in this table: the most significant information source was the specialist monitoring the patient; previously diagnosed patients use multiple resources, whilst newly-diagnosed subjects basically rely on their specialist exclusively; the major role played by patient associations regarding information and counselling (a resource used either alone or with other sources by 62.5% of patients). The emerging role of internet as an information resource must also be noted, as the web is now used by 25% of patients included. Most patients consider the quality of information received adequate (n = 41) or excellent (n = 17), whereas 7 patients rated it as inadequate or insufficient. Six of these seven patients who considered information inadequate were among those previously diagnosed (median 10.0 [5.0-25.0] months before inclusion), and had various information sources, including the specialist (n = 6), the internet (n = 3) and patient associations (n = 2); the fact that 3 of these 7 patients reported more than just one information source must be highlighted.

Issues relating to treatment

All 62 patients in the group diagnosed prior to inclusion were on a gluten-free diet. Regarding all 58 responders to this question, compliance -according to criteria by Morisky et al. (9)- was correct ("I always strictly stick to my diet") in 48 patients (82.7%). Unintentional non-compliance was recorded for 9 patients (15.5%) -3 because of forgetfulness and 6 because of neglect- and intentional non-compliance was recorded for 1 (1.8%), who discontinued his diet because of being without symptoms. According to patient views, gluten-free diet had improved symptoms in 58 of 59 who answered this question. Thirty-six patients reported full symptom remission (61.0%), with the rest reporting significant (n = 20, 33.8%) or modest (n = 2, 5.2%) improvements.

Attempts have been made at establishing the factors that may influence gluten-free diet compliance. The first variable considered has been the opinion on diet accessibility -75.8% of all 58 patients who answered consider it a somewhat complicated issue, 7.0% state their diet is very difficult to follow, and only 17.2% consider diet adherence easy. As expected, 66.6% of patients considering diet adherence difficult are non-compliant, while only 10.0% of those considering it an easy issue fail to comply; differences, however, do not reach statistical significance (p = 0.2). Another factor analyzed was the opinion of patients regarding information on their selected foods. Of all 62 patients who answered about their being informed on foods they could eat, 46.7% considered themselves adequately informed, 29.0% thought they were informed but had many doubts, and 24.3% considered themselves inadequately informed. This suggests that virtually half of the patients included had serious doubts on the foods making up the diet they must comply with. Despite this, among the 15 patients who considered themselves inadequately informed on the foods they may eat, only 2 unintentionally fail to comply with their diet, and none was intentionally non-compliant.

While suggested in other publications (14), compliance with a gluten-free diet is not associated with age in a statistically significant manner (35.0 [30.0-51.0] in compliers vs. 36.0 [28.0-54.0] in non-compliers, p = n.s.), nor with treatment duration (66.0 [24.0-132.0] months in compliers vs. 70.0 [27.7-180.0] months in non-compliers) or lower education (12 patients of 48 compliers vs. 2 patients of 8 non-compliers has at most primary education, p = n.s.).

An a priori relevant aspect of diet adherence is easiness in finding gluten-free foods. Thirty-six patients report that finding gluten-free food is an easy task (62.0%), but 40% of patients claim moderate difficulties (n = 19) or very serious problems in finding gluten-free food (n = 3). Another aspect related to easiness in diet adherence is the understanding of labels identifying gluten-free products. Only 12 patients (20.3%) consider that they have no problems in identifying gluten in labels. Most patients (n = 30, 50.8%) report occasional or many problems (n = 12, 20.3%), and 5 patients (8.6%) recognize their not knowing how the presence or absence of gluten may be detected in a product's label.

While most patients in the on-treatment group correctly comply with their gluten-free diet, upon asking them whether they experience any reaction when accidentally eating a product containing gluten, 32 patients (58.2%) interestingly report some sort of reaction. Most common reactions when eating a gluten-containing meal include diarrhea (n = 22), abdominal distension (n = 5), vomiting (n = 4), and allergic reactions (n = 1). It should be noted that the rate of patients with no symptoms on inadvertently eating a gluten-containing product is higher for non-intentional non-compliers (55.5% reported no symptoms when taking gluten) versus compliers (38.6%), even if statistical significance is not reached (p = 0.2).

Discussion

The present atudy analyzed issues relating to celiac disease epidemiology, presentation and therapy in the adult. Seventy-three patients diagnosed by serologic suspicion and histologic confirmation were included from hospital care. This pre-selection may entail a bias in the studied sample, but it has been a priori established that most patients are currently diagnosed or followed up in the hospital setting. As a consequence of the criteria used for inclusion, all patients were adults. However, when analyzing age at diagnosis, the fact that patients were diagnosed at any age -including the adolescence and old age- stands out. This would be consistent with previously known data suggesting that around one third of patients older than 65 with intestinal malabsorption have celiac disease (15).

Other relevant aspects of the studied sample include its origin -mostly urban- and a strong predominance of non-smokers. These factors may be associated with a sample bias because of the third-level hospital origin, but other presumptions cannot be excluded, and the higher rate of non-smokers may well be related to greater health-related concerns and healthy habits in a chronically ill group of subjects. A not surprising issue is the 10.9% rate of first-degree relatives also diagnosed with celiac sprue, similar to the 1:22 prevalence reported in the U.S. series by Fasano et al. in 4,508 first-degree relatives (16), or the 5% rate reported by Farré et al. in Catalonia regarding 69 first-degree relatives (12).

As a result of inclusion characteristics, most patients had no symptoms at the time of inclusion, as they had been previously diagnosed and were on a gluten-free diet. However, when disease presentation was analyzed, the classic form of presentation was only apparent in 54.7% of patients. This low rate of classic presentations may be presumed to be in association with the global availability of serologic screening for risk groups, while this cannot be concluded from the results of the present study. Anyway, this remark demands that the diagnostic possibility of celiac disease be borne in mind in atypical situations or even in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms, a fact already suggested in current clinical practice guidelines (17).

The most common presentation complaint in asymptomatic forms was diarrhea, but most patients (67.1%) report that their illness presented with multiple symptoms. Time with symptoms to diagnosis was one year, but during that time, according to patient opinions, symptoms were initially associated with functional disorders or with anxiety or stress. In 10 cases symptoms were initially attributed to food intolerance, including lactose intolerance; lack of response to the exclusion of the culprit food prompted further testing. This suggests that lactose intolerance presenting in an adult patient should lead to consider the possibility of an underlying celiac disease.

Once the diagnosis is reached, it is recommended that gluten be excluded from the diet, and that outcome be monitored. Given the characteristics of the population chosen, most patients are monitored in hospitals. Despite this, most patients either lose no work days yearly or only lose a one or two. Monitoring the dietary exclusion of gluten managed to improve symptoms in virtually all patients. This is maybe why diet compliance -according to Morisky's criteria- has been highly satisfactory, with only 17.3% of non-compliers, most of them involuntarily (from forgetfulness or neglect). Despite this, 75% of patients considered diet adherence complicated, which translates in the fact that patients who consider adherence complicated are those who most commonly fail to comply. A number of reasons may explain difficulties in diet adherence, including information quality and accessibility or difficulty in understanding labels to identify the presence of gluten in manufactured products. It is because of these reasons that both medical and social measures should be sought in order to facilitate gluten-free diet compliance. In this respect, new European regulations to be in force in the near future are expected to facilitate diet adherence, as it makes manufacturers include gluten among the ingredients listed for their foods and beverages.

Regarding the question of what happens when a celiac patient eats gluten half of cases report some sort of reaction -with diarrhea being most common- but many patients report no immediate adverse event. This is relevant as patients who tolerate "occasional" gluten exposures with no apparent symptoms tend to be poorer compliers. Hence patient follow-up and information is very important, as it should prevent the development of late complications associated with long-term gluten exposure.

To conclude, celiac disease presents at any age in a multiform manner, and responds to a gluten-free diet. Hence it is essential that patients be adequately informed and made certain of those foods and manufactured products they may take. Therefore, this disease will escape proper control pending coordination and cooperation among all resources involved, including medical care and information through associations and other sources such as the internet.

References

1. Alaedini A, Green PHR. Narrative review: celiac disease, understanding a complex autoimmune disorder. Annals Intern Med 2005; 142: 289-98. [ Links ]

2. Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 636-51. [ Links ]

3. Riestra S, Fernández E, Rodrigo L, García S, Ocio G. Prevalence of coeliac disease in the general population of northern Spain. Strategies of serologic screening. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000; 35: 398-402. [ Links ]

4. Casellas F, Accarino A, Salas A, López Vivancos J, Guarner L. Enfermedad celiaca del adulto. Med Clin 1985; 84: 46-50. [ Links ]

5. Campo C, Alonso R, Montero M, Todolí J, Bosch N, Calabuig JR. Enfermedad celíaca del adulto: estudio de 21 casos y revisión de la bibliografía. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 24: 236-9. [ Links ]

6. Case S. The gluten-free diet: how to provide effective education and resources. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: S128-S134. [ Links ]

7. Butterworth JR, Banfield LM, Iqbal TH, Cooper BT. Factors relating to compliance with a gluten-free diet in patients with coeliac disease: comparison of white Caucasian and south Asian patients. Clin Nutr 2004; 23: 1127-34. [ Links ]

8. NIH Consensus Development Conference Statement: Celiac Disease. Available at: http: //consensus.nih.gov/cons/118/118celiacPDF.pdf (30 de septiembre de 2004). [ Links ]

9. Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 1986; 24: 67-74. [ Links ]

10. Casellas F, López Vivancos J, Malagelada JR. Percepción del estado de salud en la enfermedad celíaca. Rev Esp Enferm Dig (en prensa). [ Links ]

11. Instituto de Información Sanitaria-Agencia de Calidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Encuesta Nacional de Salud, Consumo de tabaco. Elaborado por la Dirección General de Salud Pública y publicado el 26.4.2005. Disponible en: www.msc.es/sns/observatorioSNS/pdf/informe anual 1parte.pdf [ Links ]

12. Farré P, Humbert P, Vilar V, Varea X, Aldeguer J, Carnicer M, et al, Catalonian Coeliac Disease Study Group. Serological markers and HLA-DQ2 haplotype among first-degree relatives of celiac patients. Dig Dis Sci 1999; 44: 2344-9. [ Links ]

13. López-Hoyos M, Bartolomé MJ, Castro B, Fernández F, de las Heras G. Cribado de la enfermedad celiaca en familiares de primer grado. Med Clin 2003; 120: 132-4. [ Links ]

14. Ciacci C, Cirillo M, Cavallaro R, Mazzacca G. Long-term follow-up of celiac adults on gluten-free diet: Prevalence and correlates of intestinal damage. Digestion 2002; 66: 178-85. [ Links ]

15. Alonso C, Casellas F, Chicharro ML, de Torres I, Malagelada JR. Ferropenia: no siempre son pérdidas. Anales Med Int 2003; 20: 227-31. [ Links ]

16. Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Colletti RB, Drago S, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 286-92. [ Links ]

17. Bai J, Zeballos E, Fried M, Corazza GR, Schuppan D, Farthing MJG, et al. WGO-OMGE Practice Guideline. Celiac disease. World GE News 2005; 10: 1-8. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Francesc Casellas.

Servicio de Digestivo.

Hospital Universitari Vall d´Hebron. Pg. Vall d´Hebron, 119.

08035 Barcelona.

Fax: 93 489 44 56

Recibido: 09-12-05

Aceptado: 23-01-06

texto en

texto en