Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.98 no.9 Madrid sep. 2006

POINT OF VIEW

Sedation/analgesia guidelines for endoscopy

Directrices "guidelines" de sedación/analgesia en endoscopia

L. López Rosés and Subcomité de Protocolos of the Spanish Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (SEED)*

Hospital Xeral de Lugo. Lugo, Spain

*Subcomité de Protocolos de la SEED is made up of members in Comité de Docencia e Información de la SEED: J. Boix Valverde, J.R. Armengol-Miró, J. M. Pou Fernández, J. Jiménez Pérez, J. Pérez Piqueras, T. Sala Felis, D. Delgado Bellido, V. Tejedo Grafia, M. Muñoz Navas, E. castillo Bejines, J. Dot Bach

Introduction

Endoscopic examinations are invasive procedures that turn out uncomfortable and unpleasant to a lesser or greater extent, and whose tolerability by patients is variable. Because of this, and consistent with well-being society trends, patients increasingly request sedation/analgesia to better tolerate these procedures, as recommended by a number of studies (1). In medicine simpler procedures are safer, and any additional medical action will build up risk. Therefore patients should be aware that sedation increases the potential for adverse effects. The role of endoscopy units will be to optimize facilities, staff training, and monitoring means so that such complications are kept to a minimum, or adequately managed should they arise.

Objective

The objective of these Guidelines is to define: how, to whom, where, and by whom should sedation/analgesia be administered regarding patients undergoing gastrointestinal endoscopy.

The standard procedure for upper or lower diagnostic endoscopy usually consists of minimal sedation or anxiolysis, which may be complemented with analgesis when needed (the addition of drug effects leads to adverse effect enhancement, and not always is necesssary). When a prolonged, complex, or particularly troublesome or painful examination is foreseen, deeper patient sedation may be required.

Potential subjects for sedation include all patients undergoing endoscopy, provided they have a favorable risk: benefit ratio. Endoscopy type, characteristics, and duration, as well as the patient's history of good or poor tolerability should all be assessed. Information briefing and an informed consent are also essential (2). Regarding some patient characteristics (severe cardio-respiratory disease, unstable concurrent conditions, anatomic abnormalities or variations entailing potential intubation difficulties, etc.) a pre-sedation assessment is advisable, and information provided by complementary tests (ECG, laboratory tests, chest x-rays, etc.) may be necessary. Patients should be accompanied by a family member or friend, and cannot drive for at least 6 hours after endoscopy (this time may be longer depending upon the drug used).

The place where endoscopy is performed must be properly equipped for sedation. Oxygen, an aspiration system, a pulse oximeter, and resuscitation equipment should all be available.

By whom? By someone qualified to do it. Guidelines from other societies (ASA) include rules that establish requirements to be met by physicians other than anesthesiologists in order to perform sedation. All gastroenterology residents learn and apply cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers during their stays at emergency rooms, and also receive training on sedation and monitorization during their periods in endoscopy units. One should be knowledgable and familiar with methods for airway patency maintenance, as well as with tracheal intubation if needed. In endoscopy units at some hospitals sedation is performed by anesthesiologists, but not for all patients; anesthesiologists should therefore cooperate with endoscopists to provide accurate guidance on how should sedation be administered in endoscopy units, using what monitoring means, etc. Nursing staff training in pre-sedation protocols, care and monitoring during sedation, and post-sedation follow-up under direct control by endoscopists and/or anesthesiologists is a useful and much needed measure.

Sedation levels

Sedation has no fixed, pre-established levels (a given dose not always corresponds to a given sedation level) but represents a continuum -it is initiated at a minimal dose to which each patient responds in a variable, individual way; dose increases or booster doses may keep this level of sedation or progress to another level until deep sedation or even anesthesia is reached.

Four sedation levels -from lesser to greater depth- are considered (3-5):

-Minimal sedation or anxiolysis.

-Moderate sedation and analgesia, or conscious sedation (the patient responds to verbal or tactile stimuli).

-Deep sedation and analgesia (the patient responds to painful stimuli).

-Anesthesia (the patient does not respond to painful stimuli). Ventilation support may be required.

The level that is usually required for conventional endoscopy is that of minimal sedation and conscious sedation. Deep sedation may be required for some complex therapeutic procedures.

In general, anesthesiology and digestive endoscopy scientific societies have established protocols to guide sedation by physicians other than anesthesiologists, and restrict such sedation to patients with a low anesthetic risk, and to those with a high anesthetic risk (ASA 3 or higher) not requiring deep sedation; the presence of an anesthesiologist is to be preferred in the remaining cases (6).

Drugs used

A number of available drugs are useful for sedation/analgesia (benzodiazepines, fentanyl, propofol, meperidine), and for some of these there are also antagonists (flumazenil, naloxone) to neutralize ovsersedation effects. An ideal drug would have a rapid onset of effect, and would also result in a predictable sedation level (7).

The following table summarizes the major characteristics of these drugs (8) (Table I).

Sedation complications

Sedation/analgesia is a safe procedure that is, however, not exempt from complications, including: pain at puncture site, dizziness, hypotension, drug allergy, hematoma at vein puncture site, painful drug extravasation, hallucination, myoclonus, seizures, confusion, coma, constipation, urine retention, pruritus, facial redenning, arrhythmias, hypertension, vagal illness-bradycardia, bronchoaspiration, myocardial ischemia, oxygen desaturation, respiratory depression-apnea, and even cardiorespiratory arrest.

In order to prevent complications history taking should focus on the following: allergies to anesthetics, eggs, and soy; history of problems with previous anesthesias or intubations; history of substance abuse; history of antidepresssant, neuroleptic or cardiologic agent usage, etc. To try and predict which patients may be more likely to pose difficulties regarding airway patency the following should be considered: history of problems with previous anesthesias, presence of sleep apnea, stridor or snoring; patients with facial dysmorphias (Pierre-Robin syndrome) or trisomy 21; patients with oral cavity abnormalities (open mouth smaller than 3 cm, protruding incisors, high-arched palate, macroglossia, tonsillar hypertrophy or nonvisible uvula); patients with neck abnormalities [morbid obesity, short neck, limited neck extension, endothoracic goiter, neck mass, reduced hyoid-mental distance (< 3 cm)]; patients with mandibular abnormalities (micrognatia, retrognatia, trismus).

To prevent or reduce desaturation and/or hypoxemia events oxygen therapy may be administered via a nasal cannula or adapted mouth gag to sedated patients during endoscopy; however, it should be borne in mind that this may delay apnea detection by pulse oximeters (9,10).

In 1991 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration published a survey that reported a frequency of 5.4 cardiopulmonary complications per 1,000 endoscopy-related sedation procedures, which entailed a mortality of 0.03% (11). A similar study from Switzerland reported sedation-related complications in 0.1% of 115,200 procedures, with no mortality (12). A new, recently published Swiss study of 179,953 procedures where various sedation types -including propofol- were administered reported a complication rate of 0.18% and a related mortality rate of 0.0014% (13).

Monitoring

Any patient undergoing sedation/analgesia must be monitored to better control his or her vital signs during the procedure. Conscience status, pain suppression, and cardiovascular and respiratory function should be monitored. To this end the patient' s baseline, intraprocedural, and postprocedural heart rate and oxygen saturation (pulse oximeter) values should be available. All these parameters should be recorded on a specific form for each patient undergoing sedation.

For patients with heart disease or other concomitant conditions (ASA 3) a more comprehensive monitoring including blood pressure, ECG, and respiratory rate is advisable.

Instrumental monitoring (pulse oximetry, ECG and BP monitors) should not exclude visual surveillance regarding skin coloration, type of spontaneous breathing, respiratory movement intensity, etc., which cannot be replaced by monitorization devices alone.

Capnography may be useful in seriously ill patients with multiple conditions who will undergo long-term sedation for prolonged or complex endoscopy procedures (ERCP, prosthesis placement, etc.). This monitorization measures ventilatory activity, and predicts potential respiratory depression before the pulse oximeter may detect desaturation.

It is advisable to have a resuscitation system available, and a defibrillator is also recommended for complex patients with heart disease.

Patient discharge

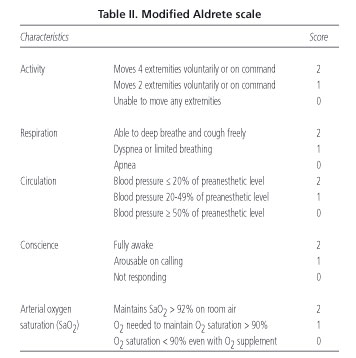

Following sedation/analgesia patients must remain at the Unit until recovery to baseline consciousness occurs, whether with proper monitorization in an examination room or in an ad-hoc recovery room. The nursing staff should monitor the patient during this stage. At discharge it is advisable that patients are provided with written instructions, and a telephone number for consultations regarding subsequent recovery. Various scales will help decide when discharge is most appropriate. Aldrete scale is very simple and practical, and considers that a patient can be discharged when he/she is able to dress without help; it is based on a numeric score that requires 9 or -better still- 10 points for discharge (14) (Table II).

Who should sedate patients

As previously established, those with adequate knowledge and safety means, that is, an appropriately trained endoscopist with the help of a nurse or an anesthesiologist. An anesthesiologist will sedate patients with ASA 3 or higher requiring deep sedation (depending on the endoscopic procedure -therapeutic, prolonged, or complex); patients with a history of intolerance to standard sedatives; and patients with a foreseeable increased risk for airway obstruction from anatomic abnormalities or variants.

Endoscopic procedures exist that because of their complexity make it impossible for the endoscopist to attend to both endoscopy and sedation; in such cases (ERCP, biliary-pancreatic therapy, etc.) we deem it more appropriate that sedation be performed by an individual other than the endoscopist in charge of the procedure. We believe that such a person may be an anesthesiologist or a properly trained physician who is used to managing sedative agents, has been properly educated in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and ultimately assumes responsibility for the procedure.

References

1. Froehlich F, Schwizer W, Thorens J, et al. Conscious sedation for gastroscopy: Patient tolerance and cardiorespiratory parameters. Gastroenterology 1995; 108: 697-704. [ Links ]

2. Guidelines for training in patient monitoring and sedation and analgesia. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48 (6): 669-71. [ Links ]

3. Joint Commission on Accreditation for Health Care Organizations. Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals: the official handbook. Oak Brook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations; 2000. [ Links ]

4. New definitions: revised standarts address the continuum of sedation and analgesia. Jt Comm Perspect 2000; 20: 10-2. [ Links ]

5. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 1996; 84: 459-71. [ Links ]

6. ASGE. Guidelines for the use of deep sedation and anesthesia for G.I. endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 613-7. [ Links ]

7. Nagengast FM. Sedation and monitoring in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol 1993; 28: 28-32. [ Links ]

8. Vicari JJ. Sedation and analgesia. Gastrointest Endoscopy Clin N Am 2002; 12: 297-311. [ Links ]

9. Brandl S, Borody TJ, Andrews P, et al. Oxygenating mouthguard alleviates hypoxia during gastroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1992; 38 (4): 415-7. [ Links ]

10. Crantock L, Cowen AE, Ward M. Supplemental low flow oxygen prevents hypoxia during endoscopic cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc 1992; 38 (4): 418-20. [ Links ]

11. Keeffe EB, O'Connor KW. 1989 ASGE survey of endoscopic sedation and monitoring practices. Gastrointest Endosc 1991; 36 (3): s13-s18. [ Links ]

12. Froehlich F, Gonvers JJ, Friedd M. Conscious sedation, clinically relevant complications and monitoring of endoscopy: results of a nationwide survey in Switzerland. Endoscopy 1994; 26: 231-4. [ Links ]

13. Heuss LT, Froehlich F, Beglinger C. Changing patterns of sedation and monitoring practice during endoscopy: Results of a nationwide survey in Switzerland. Endoscopy 2005; 37: 161-6. [ Links ]

14. Aldrete JA. The post-anesthesia recovery score revisited. J Clin Anesth 1995; 7: 89-91. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Leopoldo López Rosés.

Hospital Xeral. Lugo.

Recibido: 03-08-06.

Aceptado: 04-09-06.

texto en

texto en