Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.98 no.12 Madrid dic. 2006

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Ancillary personnel faced with living liver donation in a Spanish hospital with a transplant program

El personal no sanitario de un hospital español con programa de trasplantes ante la donación de vivo hepática

A. Ríos1,2, P. Ramírez1,2, P. J. Galindo2, M. M. Rodríguez1, L. Martínez1,2, M. J. Montoya2, D. Lucas3, J. Alcaraz4 and P. Parrilla2

1Regional Transplantation Coordination. Health Service of the Autonoma Community of Murcia. 2Department of Surgery. University Hospital "Virgen de la Arrixaca". El Palmar. 3Hospitalary Coordination of Transplants. "Reina Sofía" Hospital. 4Hematology Service. University Hospital "Virgen de la Arrixaca". El Palmar. Servicio Murciano de Salud. Murcia, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: ancillary hospital personnel represent an important body of opinion because as they work in a hospital their opinion has more credibility for the general public as a result of their activity in hospitals. However, in most cases they do not have any health care training which means that their attitude could be based on a lack of knowledge or unfounded fears. The objective of this study is to analyze the attitude toward living liver donation among ancillary personnel in a hospital with a cadaveric and living liver organ transplant program and to analyze the variables that might influence such attitude.

Patients and method: a random sample was taken which was stratified by service (n = 401) among ancillary personnel in the hospital. Attitude was evaluated using a survey that was validated in our geographical area. A representative from each service was contacted. This person was given an explanation of the study and was made responsible for the distribution of the questionnaire in selected work shifts. The survey was completed anonymously and was self-administered. The c2 test, Student's t-test and logistical regression analysis were used in the statistical analysis.

Results: the questionnaire completion rate was 94% (n = 377). Of all the respondents, 20% (n = 74) are in favor of donating a living hemi-liver, but an additional 62% (n = 233) are in favor if donation is for a relative. Of the rest, 8% (n = 30) do not accept this type of donation and the remaining 11% (n = 40) are unsure. The following variables are related to attitude toward living liver donation: attitude toward cadaveric donation (p = 0.002); a respondent's belief that he or she might need a transplant in the future (p < 0.001) and a willingness to receive a donated living liver if one were needed (p < 0.001). In the multivariate analysis the following have been found to be significantly related variables: a) a respondent's belief that he or she might need a transplant in the future (OR = 1.5); and b) a willingness to receive a living donated kidney if one were needed (OR = 16.2).

Conclusions: attitude toward living liver donation is fairly favorable among ancillary personnel in a transplant hospital and is not affected by the psychosocial factors found to be related to attitude toward donation in previous studies. However, if we want to encourage this type of transplantation with living donors it will be necessary to carry out informative campaigns to raise awareness within the hospital.

Key words: Related living liver donation. Hospital personnel. Ancillary personnel. Attitude. Donation.

Introduction

In spite of Spain having the highest rate of cadaveric donation in the world, there is an increasing shortage of liver organs available for transplantation (1). This situation means that so far in the 20th century the mortality rate on the liver transplant waiting list ranges between 8 and 10% (1). An attempt has been made to reduce the deficit by encouraging split-liver transplants for two adults, domino transplants, the use of "suboptimal" donors, and living donors (2,3). However, while the transplantation of the right hepatic lobe of a living donor for an adult recipient is becoming an accepted practice and is even increasing in Japan, the USA and some European countries (4-7), in Spain, its use is minimal (1).

One of the barriers that prevent the development of living donation could be the attitude of health care workers who are not always in favor and therefore do not create the right social climate for its implementation. In this respect ancillary workers in hospital centers are an important body of opinion because as they work in a hospital their opinion and attitude holds more credibility for the general public. However, they do not have health training in most cases, which means that their attitude could be based on a lack of knowledge or unfounded fears. Therefore it is important to find out about their attitude and the factors that influence it in order to be able to design promotional activities directed at this hospital subgroup.

The objective of this study is to find out about the structure of attitude toward living liver donation of ancillary workers who work in a hospital with a cadaveric solid organ transplant program and with a living liver and living kidney donation program and to analyze the variables that influence this attitude.

Material and methods

Study population

The study was carried out at a Spanish tertiary hospital with a cadaveric organ transplant program (kidney, liver, pancreas and heart), a living donation program (kidney and liver) and a tissue transplant program. A random sample was taken and stratified according to service among ancillary hospital personnel [employees who work in clinical services but who do not have any clinical training and are not involved in any type of clinical activity (administrative officers and porters) or in hospital services that do not involve any training or health care activity (porterage, administration, cleaning, kitchen and installation maintenance)]. A total number of 401 workers were selected and the study was carried out between February and December 2003.

Attitudinal survey and study variables

Attitude toward organ donation was evaluated using a survey validated in our geographical area (8-10). For the distribution of the survey contact was made with an administrative worker in clinical services and with the person responsible for each ancillary service (cleaning, laundry, etc.). These representatives were given an explanation of the study and were made responsible for the distribution of the survey in selected work shifts. The questionnaire was given out at the beginning of the working day. This is a time that provided access to all the selected personnel and the questionnaire was completed at that precise time (it took 3 to 5 minutes to complete the survey). The survey was completed anonymously and was self-administered. The process was coordinated by two health care workers from the Regional Transplant Center.

Attitude toward related and unrelated living liver donation was analyzed as the dependent variable. The following were analyzed as independent variables: a) age; b) sex; c) marital status (single, married, divorced, widowed or separated); d) the respondent's job contract situation (permanent or contracted); e) personal experience (through a family member of friend) of organ donation or transplantation; f) attitude toward cadaveric organ donation; g) participation in voluntary type pro-social activities; h) having discussed the subject of organ donation and transplantation within the family; i) concern about possible mutilation after donation; j) a respondent's religion (Catholic or non-Catholic); k) the attitude of a respondent's partner toward organ donation and transplantation; l) a respondent's evaluation of his or her need for a hypothetical transplant in the future; m) a respondent's willingness to receive a donated living liver if one were needed; and n) attitude toward living kidney donation.

Statistical analysis

The data were stored on a database and were analyzed using the SPSS 11.0. statistical package. Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out on each of the variables. Student's t-test and the c2 test complemented by an analysis of the remainders were applied in order to compare the different variables. Fischer's exact test was applied when the contingency tables had an expected frequency of < 5. In order to determine and evaluate multiple risks a logistical regression analysis was applied using the variables that had a statistically significant association in the bivariate analysis. Only values of p less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Attitude toward living liver donation

The questionnaire completion rate was 94% (377 valid surveys out of a total of 401 collected). Of those surveyed, only 20% (n = 74) are in favor of the living donation of a hemi-liver, but an additional 62% (n = 233) are in favor if donation is for a relative. Of the rest, 8% (n = 30) would not accept living liver donation and the remaining 11% (n = 40) are undecided.

31% (n = 117) believe that in the future there is a possibility that they might need a transplant, 1% (n = 5) believe that they will never need one and 68% (n = 255) are undecided about the matter. What is more, when a respondent considers whether or not he or she would be willing to be a recipient of a hemi-liver donated by a family member, 54% (n = 205) would be willing to receive one, 6% would not (n = 24) and 39% are unsure (n = 148).

Bivariate analysis of the factors that influence attitude

An analysis of the variables that influence attitude toward living liver donation (Table I) shows that no differences have been found with respect to the following factors: age; sex; marital status; job situation; type of service in which the respondent is based; job activity related to transplantation; personal experience of the organ donation and transplantation process or participation in pro-social voluntary type activities. On the other hand, attitude toward living liver donation is influenced by attitude toward cadaveric donation. Thus, those who would donate their organs upon death have a more favorable attitude to unrelated donation (24 versus 12%) as well as to related donation (85 versus 75%) (p = 0.002).

Other factors that do not affect attitude are: having discussed the subject of donation or transplantation within the family; fear of mutilation of the body after donation; a respondent's religion; knowing that one's religion is in favor of organ donation and transplantation and knowing the attitude of one's partner toward donation and transplantation.

Those respondents who believe that they might need a transplant in the future tend to have a more favorable attitude toward living liver donation. Thus, 88% of those who believe that they might need a transplant are in favor, compared to 80% among those who are unsure and 20% among those who believe that they are never going to need a transplant (p < 0.001). Being willing to receive a hemi-liver donated by a family member or a friend if it were necessary is another factor that is positively associated to a favorable attitude toward living liver donation. Thus, 97% of those who would be willing to receive one are in favor, compared to 46 and 66% respectively of those who would not accept one or who are unsure (p < 0.001).

Finally, there is a clear association between attitude toward living kidney donation and attitude toward living liver donation (p < 0.001).

Multivariate analysis

In order to carry out a multivariate analysis attitude was grouped into two categories: a) in favor of related living liver donation; and b) not in favor of related living liver donation, including those who are against and those who are undecided.

In this analysis two variables were found to be statistically significant independent factors affecting attitude toward living liver donation: a) a respondent's belief in the possibility of needing a transplant in the future (OR = 1.5); and b) a willingness to receive a donated living liver if one were needed (OR = 16.2) (Table II).

Discussion

Unlike the situation in living kidney donation (where many studies have been undertaken) (8,11-12) studies of attitude toward living liver donation are uncommon (13) and none have specifically analyzed the attitude of ancillary personnel in health care centers. This means that nothing is known about their attitude toward this type of donation, making it difficult to design strategies aimed at encouraging this type of donation.

Living liver donation is a type of donation that is risky for the donor because morbidity is often reported especially biliary fistulas and mortality occurring in 1-2% of donors (5-8,14). However, the nature of liver transplantation means that it is a viable therapeutic option given that the only alternative for a patient on the waiting list who does not receive a liver is death (1) and there is no kind of "dialysis" that can keep a patient alive as is the case with kidney patients. In addition, due to the experience gained by surgical teams in specialist referral centers, the risks for the donor have been significantly reduced (6).

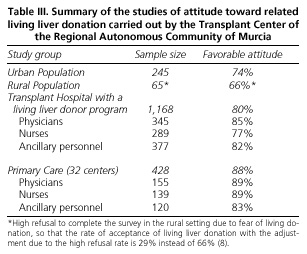

Hospital personnel tend to have quite a favorable attitude toward living liver donation. In fact it is more favorable than that described in the general public in our country (8) and in other European countries (15), where rates are at around 75% in favor. These rates refer to related living liver donation, that is, where there is some kind of relationship between the donor and the recipient, which explains the high level of acceptance in all groups, both among the general public (8,15), as well as among health care workers (9,10). As shown in table III, the Transplant Center of the Regional Autonomous Community of Murcia has analyzed attitude toward living liver donation in many groups and at many levels (8-10). As a general rule it has been seen that attitude is less favorable in the general public (74% in urban areas and 29% in rural areas) than among personnel in health care centers. In this latter group, primary care personnel have a more favorable attitude (88%) than hospital personnel working in a center with a living liver donor program (80%). Regarding ancillary personnel, it has been seen that there is a similar attitude among those who work in primary care (83%) and those who work in the hospital (82%). Also, their attitude is more favorable than that of the general public.

We have found that the attitude of ancillary personnel toward living liver donation is not influenced by the classic psycho-social factors that influence attitude toward cadaveric donation, although it is related to the respondent's attitude toward cadaveric donation. This coincides with data for the general public, which show a clear positive association with respect to attitude toward cadaveric donation (8). However this relationship is not as clear as it is with the general public: in the multivariate analysis it is not a significant variable although it is on the borderline of statistical significance. A close association has also been found between attitudes toward living kidney and living liver donation, which suggests that the main problem with living donation is its acceptance (9,10).

Of the remaining variables, there is only one significant association with two factors that are closely related to feelings of reciprocity, that is, doing for others what you would like to be done for yourself: a respondent's belief that in the future there is the possibility that he or she may need a transplant and a willingness to receive a donated living liver if one were needed. These two factors clearly encourage a favorable attitude toward living liver donation.

The favorable predisposition of ancillary personnel could be used as a source to promote living donation, above all in those areas of the population where attitudes are most negative (8). Living donation needs to be developed in Spain and could provide a potential source of organs which is greater than that provided by cadaveric organs, although, it should be remembered that for a variety of reasons, out of all the people considered as potential donors, only 10-20% actually become donors.

In spite of this potential, some caution should be taken in the development of living liver donation. This is because when we analyze the situation in other countries where this technique has been developed we find that living liver transplantation from one adult to another is becoming more common but it is only carried out by a few specialist centers with a high volume of cases and where there is extensive experience (16), with the objective of reducing morbidity and mortality. What is more, it should be remembered that each recipient has a number of potential liver donors who are subjected to a series of invasive procedures such as (arteriography, etc.) that cause morbidity in them even if they do not become actual donors (16,17).

However, it has been seen that in spite of: a) the need for living donation (1); b) the interest of transplant teams; and c) the favorable attitude of the general public (8) and of the hospital personnel (9,10), as seen in this study, this type of donation continues to be minimal. Although it would be the subject of a further study this is possibly due to the fact that this favorable attitude is not converted into a real demand for living donation from families of patients on the waiting list. What is more, the attitude of Spanish patients is different to that of patients from other countries. A Spanish patient knows that in a relatively short time he or she could receive a cadaveric organ and prevent a family member from losing one of theirs while alive, whereas in other countries the cadaveric organ donation rate is very low and waiting times are longer (18).

To conclude we could say that ancillary hospital personnel are quite in favor of living liver donation, especially if it is related, in spite of the risk of morbidity and mortality for the donor, and that this attitude is not influenced by the classic psycho-social factors previously described as being associated with attitude toward donation. However, if we really want to encourage this type of transplantation with living donors it will be necessary to continue to organize informative campaigns to raise awareness in hospitals.

References

1. Memoria de actividades ONT 2004 (1ª parte). Rev Esp Traspl 2005; 14 (2). [ Links ]

2. Ramírez P, Ríos A, Sánchez Bueno F, Robles R, Pons JA, Acosta F, et al. Trasplante hepático split para dos adultos. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 27 (Supl. 4): 52-7 [ Links ]

3. Parrilla P, Sanchez-Bueno F, Figueras J, Jaurrieta E, Mir J, Margarit C, et al. Analysis of the complications of the piggy-back technique in 1,112 liver transplants. Transplantation 1999; 67: 1214-7. [ Links ]

4. Settmacher U, Theruvath T, Pascher A, Neuhaus P. Living-donor liver transplantation-European experiences. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19 (Supl. 4): 16-21. [ Links ]

5. Tanaka K, Kiuchi T, Kaihara S. Living related liver donor transplantation: techniques and caution. Surg Clin North Am 2004; 84: 481-93. [ Links ]

6. Russo MW, Brown RS Jr. Adult living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant 2004; 4: 458-65. [ Links ]

7. Ghobrial RM, Busuttil RW. Future of adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2003; 9 (Supl. 2): 73-9. [ Links ]

8. Conesa C, Ríos A, Ramírez P, Rodríguez MM, Parrilla P. Socio-personal factors influencing public attitude towards living donation in south-eastern Spain. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19: 2874-82. [ Links ]

9. Ríos A, Conesa C, Ramírez P, Galindo PJ, Martínez L, Pons JA, et al. Attitude toward living liver donation among hospital personnel in services not related to transplantation. Transplant Proc 2005; 37: 3636-40. [ Links ]

10. Conesa C, Ríos A, Ramírez P, Sánchez J, Sánchez E, Rodríguez MM, et al. Acceptance level of living liver donation among primary care nursing personnel. Transplant Proc 2005; 37: 3631-5. [ Links ]

11. Spital A. Public attitudes toward kidney donation by friends and altruistic strangers in the United States. Transplantation 2001; 71: 1061-4. [ Links ]

12. Álvarez M, Martín E, García A, Miranda B, Oppenheimer F, Arias M. Encuesta de opinion sobre la donacion de vivo renal. Nefrologia 2005; 25 (Supl. 2): 57-61. [ Links ]

13. Brown RS Jr, Russo MW, Lai M, Shiffman ML, Richardson MC, Everhart JE, et al. A survey of liver transplantation from living adult donors in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 818-25. [ Links ]

14. Karliova M, Malago M, Valentin-Gamazo C, Reimer J, Treichel U, Franke GH, et al. Living-related liver transplantation from the view of the donor: a 1-year follow-up survey. Transplantation 2002; 73: 1799-804. [ Links ]

15. Neuberger J, Farber L, Corrado M, ODell C. Living liver donation: a survey of the attitudes of the public in Great Britain. Transplantation 2003; 76: 1260-4. [ Links ]

16. Brown RS Jr, Russo MW, Lai M, Shiffman ML, Richardson MC, Everhart JE, et al. A survey of liver transplantation from living adult donors in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 818-25. [ Links ]

17. Sauer P, Schemmer P, Uhl W, Encke J. Living-donor liver transplantation: evaluation of donor and recipient. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19 (Supl. 4): 11-5. [ Links ]

18. Martínez-Alarcón L, Ríos A, Conesa C, Alcaraz J, González MJ, Montoya M, et al. Attitude toward living related donation of patients on the waiting list for deceased donor solid organ transplant. Transplant Proc 2005; 37: 3614-7. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Antonio Ríos Zambudio.

Avda. de la Libertad, 208.

Casillas. 30007 Murcia.

Fax: 968 369 716.

e-mail: ARZRIOS@teleline.es

Recibido: 10-04-06.

Aceptado: 07-09-06.

texto en

texto en