Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.101 no.10 Madrid oct. 2009

CLINICOPATHOLOGICAL CONFERENCE

Ascites and diarrhea

Ascitis y diarrea

M. Amo Peláez, S. Rodríguez Muñoz, G. Castellano Tortajada and J. A. Solís Herruzo

Service of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Universitario "12 de Octubre". Madrid, Spain

Dr. S. Rodríguez. We report the case of a 42-year-old male who presented with diarrhea, abdominal pain, ascites, and edema while travelling in Egypt, and was consequently diagnosed with liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension. He had already presented to the emergency room with edema. The physical exam revealed a distended, soft, non-tender abdomen with positive ascitic wave, as well as edema in the lower limbs. He was discharged on a salt-free diet, compression pantyhose, and advice to undergo further testing by his primary care physician. An ultrasonogram performed in Egypt revealed homogeneous hepatomegaly with no space-occupying lesions, a 16-mm portal vein, bile bile mud, and overt ascites. Two months later the patient attended the gastroenterology clinic with suspicion of liver cirrhosis. He reported asthenia, weight loss (5 kg), malleolar edema, and light-colored soft feces for the last few months. His medical history included: hepatitis A during childhood, and three doses of VHB vaccine. A relative of his had been diagnosed with autoimmune liver disease. He reported no alcohol ingestion. The patient produced lab test results with interestingly normal transaminase levels.

Physical exploration revealed a hard, non-tender hepatomegaly but no evidence of ascites or edema. New lab tests showed: GOT 31 IU/l, GPT 39 IU/l, GGT 7 IU/l, albumin 2.9 g/dl, total bilirubin 0.4 mg/dl, iron 88 μg/dl, ferritin 3.7 ng/ml, copper 65 μg/dl, ceruloplasmin 17 mg/dl, urine Na 90 mEq/l, urine K 25 mEq/l, Hb 13.8 g/dl, platelets 325,000/μl, WBCs 7,400 μl and normal differential, prothrombin activity 66%, TTPA 34, anti-smooth muscle antibodies 1/20, and negative anti-nuclear, anti-mitochondrial, and anti-LKM antibodies. Amylase 85 U/L, urine copper and 24-hour urine porphyrins within the normal range, and negative c-ANCA and p-ANCA. Anti-gliadin IgG antibodies 5.5 IU/ml (normal < 2.5 IU/ml), anti-gliadin IgA antibodies 0.86 IU/ml (normal < 1.5 IU/ml). Vitamin B12 and folic acid levels: normal. Serologic tests for hepatotropic viruses were positive for hepatitis A virus (IgG antibodies). Anti-HBs antibodies were also positive. Thyroid hormones were within the normal range. A gastroduodenal radiographic study and intestinal follow-through were obtained that revealed no lesions, and a new abdominal ultrasonogram revealed a liver with irregular contour, homogeneous echogenicity, and no space-occupying lesions or ascites; patent portal vein, 13.7 cm in diameter, with hepatopetal flow (21 cm/s), and 13-cm spleen with a bipolar axis. No free fluid was identified within the abdominal cavity. Ultrasonographic judgment: image suggestive of chronic liver disease with portal dilation. Gastroscopy revealed no pathological findings and specifically no esophageal varices or other evidence of portal hypertension was identified; the second portion of the duodenum had normal morphology.

Based on these data a previously performed lab test and exploration were repeated, which proved diagnostic.

Differential diagnosis

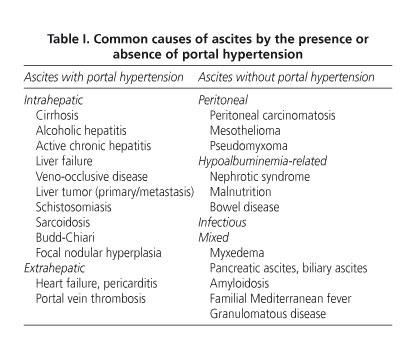

Dr. M. Amo. In summary, this is a 42-year-old male with a family history of autoimmune liver disease who seeks help for edema and ascites, reason why he had previously been diagnosed with liver cirrhosis, all of it preceded by an episode of diarrhea and light-colored stools. In the lab tests only the presence of hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia was outstanding. Ultrasounds demonstrated ascites, a normal-looking liver, and portal vein dilation with no other signs of portal hypertension. Gastroscopy showed no esophageal varices. So, we will start the diagnostic discussion on this patient by focusing on one of his most striking symptoms, namely ascites. An approach to this would consider the serum-ascites albumin gradient (1); however, this was impossible to do with this patient since ascites had already resolved when he presented to our clinic. Therefore, we will differentiate ascites based on the presence or absence of portal hypertension (PH). Table I lists the most common causes of ascites.

The most common cause of ascites with PH is liver cirrhosis (2), which is responsible for ascites in nearly 75% of patients (2). In this case we mayexclude an alcoholic or drug-related/toxic origin given that there is no history of heavy drinking or drug use. Similarly, we may exclude viral cirrhosis given that serologic tests for hepatotropic viruses yielded negative results, except for vaccination against HBV and previous infection with HAV. I must also consider non-alcoholic fatty liver disease since up to 20% of the population has this condition, which is estimated to be the third most common cause of liver disease in Spain, following HCV and alcohol. However, there is an absence of factors associated with this condition (3,4), including metabolic syndrome (insulin resistance, type-2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipemia, central obesity), no history of parenteral nutrition, normal liver tests (3,4), and absence of bright liver echo pattern on ultrasounds (4). Given the patient's family history, I will also cite autoimmune liver diseases. However, non-organ-specific autoantibodies were negative, including anti-mitochondrial antibodies, which are common in primary biliary cirrhosis (5), pANCA, more common in primary sclerosing cholangitis, anti-nuclear or anti-smooth muscle antibodies, etc. (6). Despite the patient's asthenia, anorexia, and weight loss, lab tests suggested no cholestasis (6), hence primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis are unlikely. We also considered metabolic liver conditions for the differential diagnosis. Hereditary hemochromatosis is a genetic disease that mainly results from C282Y mutation in gene HFE. This mutation is present in up to 90% of patients with typical hemochromatosis (7,8). The mutation conditions excessive intestinal iron absorption, hence there is abnormal iron deposition in various organs (brain, heart, liver). It manifests with weakness, abdominal pain, joint pain, diabetes mellitus, dark skin pigmentation, etc., (7) in addition to symptoms originating in involved organs. Our present patient had no diabetes mellitus, melanic pigmentation, joint disease, or heart disease. Blood ferritin was low. Therefore I can rule out this disease (7). I also should exclude Wilson's disease, which results from genetic ATP7B deficiency - biliary copper excretion is highly decreased, which determines a pathological deposition of copper in the liver and then in many other tissues, mainly the brain (9-11). Major neurological symptoms include the presence of choreiform movements, muscular dystonia, dysarthria, tremor, etc. The finding of Kayser-Fleischer corneal rings is common in such cases. Liver manifestations are highly variable, and may oscillate between mild transaminase alterations and chronic hepatitis, mimicking at times autoimmune hepatitis; they can also present as fulminant liver failure (9-11). In this disease plasma ceruloplasmin levels are reduced, urine copper is increased, and copper concentrations in the liver are above 250 μg/gram of dry tissue. The patient's family history of -allegedly- autoimmune liver disease and mildly reduced ceruloplasmin levels favor this diagnosis. However, blood and urine copper levels were normal and no neurological issues were unveiled during the physical exam. Liver tissue copper concentration is not available - it might have ruled out Wilson's disease (9), but this condition is nevertheless unlikely in our patient given the above-mentioned data. Porphyria cutanea tarda is also unlikely. No clinical signs usually associated with this disease are reported, including cutaneous hypersensitivity to sunlight and microtruma, hypertricosis, or hyperpigmentation. Porphyrin levels in both the blood and urine were normal. Knowing whether liver tissue shows red fluorescence under Wood's lamp would have been interesting. To conclude I must mention alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency as a cause of liver disease. I believe I can also exclude this condition since manifestations do not suggest this (age at presentation, absence of pulmonary involvement). Also in this case liver tissue histology offers valuable diagnostic findings, that is, PAS-positive globules (12). Similarly, ultrasounds allow to rule out other rare liver conditions that induce portal hypertension, including focal nodular hyperplasia, Budd-Chiari syndrome, veno-occlusive disease, portal thrombosis, and liver malignancies, both primary and metastatic.

To definitely exclude all these diseases I'd like to know whether this patient had a liver biopsy performed, as well as its findings.

Dr. S. Rodríguez. Yes, a liver biopsy with laparoscopic guidance was performed, which showed a preserved liver architecture with mild diffuse fibrosis and minimal inflammatory changes. No bile pigments, steatosis, siderosis, or PAS-positive globules were seen, and methods for copper or amyloid demonstration yielded negative results. Exposure of the biopsy cylinder to Wood's light showed no red fluorescence. Similarly, laparoscopy offered normal images of the liver and other peritoneal viscera. No masses, collateral circulation, peritoneal or omental lesions, or free fluid were found.

Dr. M. Amo. These histological findings obviously rule out all or nearly all the aforementioned liver conditions. Hence, considering that none of the discussed diseases accounts for the patient's clinical picture, I must analyze whether the patient has an ascites-inducing condition in the absence of PH. These include peritoneal conditions (carcinomatosis, mesothelioma, pseudomyxoma) and pancreatic diseases. However, all of them can be excluded since laparoscopy revealed no changes suggesting their presence. Myxedema is an uncommon cause of ascites. The study of ascitic fluid usually reveals very high protein levels (> 2.5 g/dL) (13), commonly associated with changes in thyroid hormone concentrations and manifestations of hypothyroidism. In our case we have no data to estimate the albumin gradient in ascites, but the absence of hypothyroidism symptoms and normal thyroid function in our patient make myxedema unlikely as the condition underlying ascites. Another condition to rule out is nephrotic syndrome. Despite low blood albumin levels and lower-limb edema, our patient had no associated proteinuria, hyperlipidemia, or renal disease (14).

Amyloidosis is a rare disease with deposition of insoluble, fibrillar amyloid proteins most commonly in extracellular spaces within organs and tissues, including the liver. Different types of amyloidosis exist depending on the protein predominating in tissue deposits. The secondary form is most frequent. In our patient, the absence of macroglossia and amyloid deposition in the heart, as well as the histological study of liver samples, with inconsistent staining and immunohistochemical characteristics, allowed to rule out this diagnosis. Amyloid binds Congo red stain and exhibits green birefringence with polarized light, and such things could not be found in our patient's liver biopsy (15).

The presence of intestinal lymphoma may account for weight loss, disturbed intestinal habit, and even ascites as seen in this patient. However, the absence of B symptoms such as nocturnal sweating or fever, and lack of adenopathies or masses on laparoscopy allows to reject this diagnosis. The absence of severe eosinophilia and other clinical aspects (fever, bouts of joint complaints) suggests that eosinophilic gastroenteritis and familial Mediterranean fever are unlikely.

Infectious causes should also be discussed in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly given that complaints developed while traveling in Egypt. Multiple infections may induce diarrhea and liver involvement, including infection with schistosoma, leishmania, Ascaris lumbricoides, strongyloides, fasciola, and toxoplasma. Most of these illnesses present with fever, eosinophilia, and symptoms originating in other organs, but all may be definitely excluded by the examinations performed, specifically ultrasounds, laparoscopy, and most particularly liver biopsy.

Hypoalbuminemia is characteristic in this patient. There is therefore a chance that his transient ascites resulted from low blood albumin. Malnutrition may be excluded since our patient exhibits no anthropometric measurements suggesting it. Once nephrotic syndrome has been excluded, we should mention illnesses related to bowel disease among the conditions entailing hypoalbuminemia. A differential diagnosis was made with conditions such as bacterial overgrowth and Whipple's disease (16). Bacterial overgrowth seems improbable as no predisposing factors (17) (antibiotics, prior abdominal surgery, fistula, etc.) were reported, and both B12 and folic acid blood levels were normal, even though a definitive diagnosis would be based on pathological small-bowel aspirate cultures (17), which are not available in our case. Whipple's disease is a multisystemic condition induced the bacterium Tropheryma whippelii, and may present with diarrhea, steatorrhea, abdominal pain, and on occasion weight loss, febricula, and night sweating (16). Joint complaints are apparent in up to 90% of cases, and adenopathies are common. Clinical manifestations include vitamin deficiencies or indirect evidence of malabsorption (16). Our patient is unlikely to have Whipple's disease since no data suggest so, including those obtained from exploratory laparotomy. Nor shall I consider intestinal lymphangiectasia, which usually presents during childhood. An intestinal biopsy would be most useful to exclude these conditions.

In view of the aforementioned normal exams, I will focus on the diagnosis of adult-onset celiac disease. While the condition typically develops during childhood, a considerable proportion of adults are known to have this disease despite absent, nonspecific, or non-gastrointestinal manifestations (18-24). Typical symptoms include asthenia, sideropenic anemia, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, and occasionally edema (18-20,22). Physical exploration may reveal weight loss, abdominal distension, and hepatomegaly. In addition, osteopenia, infertility, and even liver disease are also common, the latter being responsible for 2.7-5.0% of hypertransaminasemia events of uncertain origin (18,25-28). Blood biochemistry commonly shows anemia and plasma protein deficiency (18-20,22, 27,28) involving albumin, ferritin and ceruloplasmin, all of which is present in our patient. Ascites secondary to severe hypoproteinemia is a rare finding in celiac disease (29,30), which leads to suspect and exclude other ascites-inducing conditions. Diagnosis is based on measuring antitransglutaminase IgA or antiendomysium IgA antibodies, intestinal biopsy (20,22), and a gluten-free diet trial. Tissue antitransglutaminase IgA and antiendomysium IgA antibodies are extremely sensitive and specific (St: 90-98%, Sp: 94-97% vs. St: 85-98% Sp: 97-100%, respectively) (18,20,21,27). In addition, genetic factors are currently known to play a role in the pathogenesis of this disease, which is furthermore associated with HLA DQ2 and DQ8 (18,19,21,22,28,31). Being a carrier of these HLA markers is a predisposing factor.

From the above, the most likely diagnosis for this patient is celiac disease; however, for confirmation, I would like to know whether our patient had these antibodies measured, his HLA studied, and an intestinal biopsy performed.

Dr. S. Rodríguez. Indeed this patient had antitransglutaminase IgA antibodies measured, and a repeat upper endoscopy provided duodenal biopsy samples. Antigliadin IgG antibodies were 29 IU/ml, antigliadin IgA antibodies were 5.4 IU/ml, and antitransglutaminase antibodies were 185 IU/ml (normal range < 20 IU/ml). A repeat gastroscopy identified no abnormal changes, and biopsies were obtained from the second and third duodenal portions. An HLA study has been ordered but results are not available yet.

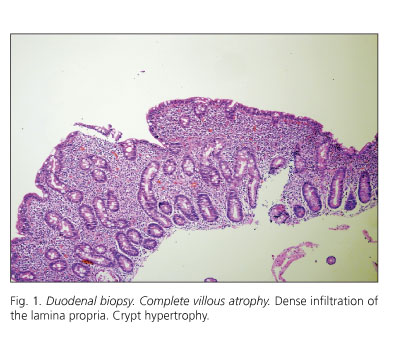

The histological examination of duodenal biopsies showed complete villous atrophy with crypt hypertrophy (Fig. 1). Superficial epithelial cells were cuboid in shape, and nuclei had lost polarity. A high number of intraepithelial lymphocytes were seen (Fig. 2). The lamina propria was densely infiltrated with lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 2).

Dr. M. Amo. This histological description is characteristic of celiac disease, specifically of Marsh stage 4 with complete bowel villi deletion and crypt hypertrophy (32,33). Furthermore, this new measurement showed highly elevated antitransglutaminase antibodies, which strongly supports a diagnosis with celiac disease. The positive predictive value of these antibodies ranges from 97 to 100% (34,35). It would be interesting to know whether a gluten-free diet was administered, and the resulting clinical and histological outcome.

Dr. S. Rodríguez. The patient was in effect diagnosed with celiac disease, hence he was advised to fully eliminate dietary gluten. In this way the patient has remained symptom-free thereafter, and a duodenal biopsy performed two years later showed a recovery of duodenal villi (Fig. 3).

Definitive diagnosis: celiac disease with complete villous atrophy and crypt hypertrophy manifesting as ascites.

References

1. Dittrich S, Yordi LM, de Mattos AA. The value of serum-ascites albumin gradient for the determination of portal hypertension in the diagnosis of ascites. Hepatogastroenterology 2001; 48: 166-8. [ Links ]

2. Moore KP, Aithal GP. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut 2006; 55: vi1-12. [ Links ]

3. Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Wei Y, Ibdah JA. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome: an update. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 185-92. [ Links ]

4. Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology 2006; 43: S99-S112. [ Links ]

5. Lazaridis KN, Talwalkar JA. Clinical epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis: incidence, prevalence, and impact of therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2007; 41: 494-500. [ Links ]

6. Angulo P, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 1999; 30: 325-32. [ Links ]

7. Adams PC, Barton JC. Haemochromatosis. Lancet 2007; 370: 1855-60. [ Links ]

8. Solís-Herruzo JA. Strategy for diagnosis and management in iron overload. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2003; 95: 351-7. [ Links ]

9. Ala A, Walker AP, Ashkan K, Dooley JS, Schilsky ML. Wilson's disease. Lancet 2007; 369: 397-408. [ Links ]

10. Solís-Muñoz P, Solís-Herruzo JA. Wilson's disease --a rare thought present condition. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100: 447-55. [ Links ]

11. Rodrigo Agudo JL, Valdés Mas M, Vargas Acosta AM, Ortiz Sánchez ML, Gil del Castillo ML, Carballo Álvarez, et al. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and long-term outcome of 29 patients with Wilson's disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100: 456-61. [ Links ]

12. Köhnlein T, Welte T. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Med 2008; 121: 3-9. [ Links ]

13. de Castro F, Bonacini M, Walden JM, Schubert TT. Myxedema ascites. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol 1991; 13: 411-4. [ Links ]

14. Ackerman Z. Ascites in nephrotic syndrome. Incidence, patients' characteristics, and complications. J Clin Gastroenterol 1996; 22: 31-4. [ Links ]

15. Rodero Astaburuaga C, Bueno Lledó J, López Baeza F, Señer Peñalva J, Peñas Pardo L, Chirivella Casanova M, et al. Intestinal pseudoobstruction and severe lower gastroinstestinal haemorrhage due to amiloidosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 354-6. [ Links ]

16. Gil Ruiz JA, Gil Simón P, Aparicio Duque R, Mayor Pérez JL. Association between Whipple's disease and Giardia lamblia infection. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2005; 97: 521-6. [ Links ]

17. Gasbarrini A, Lauritano EC, Gabrielli M, Scarpellini E, Lupascu A, Ojetti V, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: diagnosis and treatment. Dig Dis 2007; 25: 237-40. [ Links ]

18. Farrell J. Celiac sprue. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 180-8. [ Links ]

19. Ciclitira PJ, Moodie S. Coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2003; 17: 181-95. [ Links ]

20. Farrell J, Kelly P. Diagnosis of celiac sprue. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 3237-46. [ Links ]

21. Reif S, Lerner A. Tissue transglutaminase-the key player in celiac disease: a review. Autoimmun Rev 2004; 3: 40-5. [ Links ]

22. Green HR, Jabri B. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2003; 362: 383-91. [ Links ]

23. McManus, Kelleher D. Celiac Disease-the villain unmasked? N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2573-4. [ Links ]

24. Lurie Y, Landau DA, Pfeffer J, Oren R. Celiac disease diagnosed in the elderly. J Clin Gastroenterol 2008; 42: 59-61. [ Links ]

25. Barbero Villares A, Moreno Monteagudo JA, Moreno Borque R, Moreno Otero R. Hepatic involvement in celiac disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 31: 25-8. [ Links ]

26. Cantarero Vallejo MD, Gómez Camarero J, Menchén L, Pajares Díaz JA, Lo Iacono O. Liver damage and celiac disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007; 99: 648-52. [ Links ]

27. García Novo MD, Garfia C, Acuña Quirós MD, Asensio J, Zancada G, Barrio Gutiérrez S, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in apparently healthy blood donors in the autonomous community of Madrid. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007; 99: 337-342. [ Links ]

28. Rodrigo L, Fuentes D, Riestra S, Niño P, Álvarez N, López-Vázquez A, et al. Increased prevalence of celiac disease in first and second-grade relatives. A report of a family with 19 studied members. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007; 99: 149-55. [ Links ]

29. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. The liver in celiac disease. Hepatology 2007; 46: 1650-8. [ Links ]

30. Tomei E, Semelka RC, Braga L, Laghi A, Paolantonio P, Marini M, et al. Adult celiac disease: what is the role of MRI? J Magn Reson Imaging 2006; 24: 625-9. [ Links ]

31. Rodrigo L, Riestra S, Fuentes D, González S, López-Vázquez A, López-Larrea C. Diverse clinical presentations of celiac disease in the same family. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 612-9. [ Links ]

32. Farrel RJ, Nelly CP. Celiac sprue and refractory sprue. En: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors. Sleisenger & Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. p. 2277-306. [ Links ]

33. Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity ('celiac sprue'). Gastroenterology 1992; 102: 330-54. [ Links ]

34. Carroccio A, Vitale G, Di Prima L, Chifari N, Napoli S, La Russa C, et al. Comparison of anti-transglutaminase ELISAs and an anti-endomysial antibody assay in the diagnosis of celiac disease: a prospective study. Cin Chem 2002; 48: 1546-50. [ Links ]

35. Gillett HR, Freeman HJ. Comparison of IgA endomysium antibody and IgA tissue transglutaminase antibody in celiac disease. Can J Gastroenterol 2000; 14: 668-71. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M. Amo Peláez.

Servicio de Medicina de Aparato Digestivo.

Hospital Universitario "12 de Octubre".

Avda. de Córdoba, s/n. 28041. Madrid, Spain.

e-mail: mariaamo80@hotmail.com

Received: 27-03-09.

Accepted: 31-03-09.