My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.101 n.12 Madrid Dec. 2009

Adverse events of ERCP at San José Hospital of Bogotá (Colombia)

Eventos adversos de la CPRE en el Hospital de San José de Bogotá

A. Peñaloza-Ramírez, C. Leal-Buitrago and A. Rodríguez-Hernández

Service of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy. San José Hospital. Health Sciences University Foundation. Bogotá Surgery Society. Bogotá, Colombia

ABSTRACT

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has become the preferred treatment method for hepatobiliary and pancreatic disease. Despite technological progress this technique continues to account for the greatest morbidity and mortality caused by digestive endoscopic procedures. ERCP carries a risk of pancreatitis, perforation, hemorrhage, cholangitis and cardiopulmonary events occurring in upto 10% of patients in referral centers, implying a mortality of up to 1%, not including therapeutic failures or the need for re-intervention. A greater mortality rate has been demonstrated in prospective studies rather than in retrospective studies, but overall, the number of complications described in the literature is much lower than the number of complications that actually occur.

A descriptive prospective study was conducted at San José Hospital from April 1, 2006 to April 30, 2007 in patients who underwent an ERCP and had a 1-month follow-up. A total of 381 patients were included; 9 (2.3%) were excluded, and of the remaining 372 there was an overall success in 79.6% of cases, 8.3% had a second intervention, 7.6% developed complications (pancreatitis, perforation, hemorrhage, cholangitis, pain, intolerance to sedatives, and cardiopulmonary events), and 4.3% were failed ERCP studies. The mortality rate of the ERCP procedure was 0.8%.

ERCP-related complications were determined at a teaching center, and this suggests the need to implement centers of excellence in order to improve the efficacy of the procedure.

Key words: ERCP. Complications. Mortality.

RESUMEN

La colangiopancreatografía retrograda endoscópica (CPRE) se ha convertido en el procedimiento terapéutico por excelencia de la vía biliopancreática. A pesar de los avances tecnológicos continúa siendo la técnica con mayor morbimortalidad de la endoscopia digestiva. Las complicaciones de la CPRE incluyen la pancreatitis, perforación, hemorragia, colangitis y eventos cardiopulmonares que en centros de referencia ocurren hasta en un 10%, implicando una mortalidad hasta del 1%, sin incluir las fallas terapéuticas ni las reintervenciones. En los estudios prospectivos se ha demostrado un porcentaje mayor de morbilidad que en los retrospectivos, aunque en general, en los estudios publicados, se reconoce un porcentaje menor de complicaciones al que realmente ocurre.

Se realizó un estudio descriptivo prospectivo desde el 1 de abril de 2006 hasta el 30 de abril de 2007 en los pacientes del Hospital de San José a quienes se les practicó CPRE con un seguimiento durante un mes. Se incluyeron 381 pacientes, se excluyeron 9 (2,3%), de los restantes 372 pacientes estudiados el 79,6% fueron exitosos, el 8,3% reintervenidos, el 7,6% presentaron complicaciones (pancreatitis, perforación, hemorragia, colangitis, dolor, intolerancia a la sedación y eventos cardiopulmonares) y el 4,3% fueron fallidas. La mortalidad atribuida al procedimiento fue del 0,8%.

Se determinaron las complicaciones debidas a la CPRE en un centro de enseñanza sugiriendo el establecimiento de centros de excelencia en busca de una mayor efectividad del procedimiento.

Palabras clave: CPRE. Complicaciones. Mortalidad.

Introduction

Endoscopic techniques have become the gold standard for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions for biliary and pancreatic diseases. The current use of ERCP is mainly therapeutic and only in some very special circumstances is it done for diagnostic purposes (1-5). ERCP is the most complex digestive endoscopy technique. ERCP complexity carries a morbidity rate of up to 10% and a mortality rate of up to 1% (6-9).

A complication is defined as an adverse or undesirable event that may or may not have a precipitating cause and does not that imply a medical error or medical negligence. An adverse event occurring within 30 days following the procedure is considered an early ERCP-related complication. Complications from endoscopy are defined as general complications or they may be specific to the type of procedure (6,7). ERCP complications were classified at the 1991 consensus conference into 3 categories: mild, requiring up to 3 days' hospitalization; moderate, requiring 4 to 10 days' hospitalization; and severe, requiring more than a 10 days' hospitalization, radiologic or surgical intervention or causing death. Mortality attributable to this procedure was defined as that which occurred within 30 days after the procedure or complication.

ERCP-related complications include acute pancreatitis, post-sphincterotomy bleeding, biliary sepsis (cholangitis and cholecystitis), perforation and side effects of sedatives (arrhythmias and hypoxemia) (6-8). In recent years ERCP-related pain has been regarded as an adverse event when it is a typical 24-hour abdominal pain occurring after the procedure, after ruling out pancreatitis or perforation; and when the clinical indication for which ERCP was performed was not resolved. For, even though it does not cause direct morbidity, it does imply the need for additional diagnostic or therapeutic procedures carrying associated morbidity and mortality risks, as well as higher costs for the health care system (6).

It is assumed that different series underscore the number of complications and report less than actually occur (6,7,9,10). In a prospective telephone survey within 30 days after ERCP, the reported complication rate increased by approximately 50% (7).

The purpose of this study was to describe the determining factors of ERCP-related adverse events or success at an academic referral center.

Methods

This descriptive, prospective study was conducted in patients seen at San José Hospital in Bogotá who underwent an ERCP between April 1, 2006 and April 30, 2007. All patients for whom the procedure was clinically indicated according to the service guidelines and who signed an informed consent form were included. Patients who underwent an ERCP practiced by a professional other than the two professors in the service, and those who did not have a minimum 30-day follow-up were excluded. The two experienced professors who practiced the procedures perform an annual average of 180 ERCPs each. Despite the fact that this is a teaching hospital, no training medical procedures were conducted during the study period. Initial patient information was obtained, and follow-up was conducted, by the researchers, personally or by phone, 4 and 24 hours after the ERCP and on day 30. All the necessary calls were made in order to obtain the required information. When an abnormality was detected the patient's clinical record was directly reviewed to confirm what had happened. Additionally, all re-interventions performed in our service were included. Non-invasive monitoring methods were used. Procedures were conducted under conscious sedation with a titrated midazolam dose of up to 5 mg iv and using hyoscine N-butyl bromide as antispasmodic medication at a titrated dose of up to 40 mg iv. Both drugs were administered by a licensed nurse assigned specifically to this task. A curved sphincterotome was used for cannulation and no hydrophilic guide wires were used to facilitate the procedure. Cannulation attempts for each patient were not quantified. Since this is a referral hospital, procedure complexity was diverse and was not analyzed as a variable in this study.

ERCP was defined as a successful procedure when the clinical indication was resolved without any complication. An ERCP was deemed diagnostic when opacification with a contrast medium of the bile or pancreatic ducts was achieved according to the clinical indication and no therapeutic intervention was performed. ERCP was deemed non-successful when complications occurred, second interventions were required, or the indication remained unresolved. ERCP-related complications were reported according to the classification defined at the 1991 consensus conference (6). Pancreatitis was defined as the presence of abdominal pain within 24 hours following ERCP, with a minimum 3-fold increase of amylase above normal values. Perforation was diagnosed when the patient developed abdominal pain associated with retropneumoperitoneum in an abdominal X-ray. Cholangitis was considered when the patient had fever higher than 38 oC within 24 hours following the ERCP procedure. Hemorrhage was defined as bleeding that required an endoscopic injection for its management, anemia that required a blood transfusion, or if the procedure had to be suspended because of it. Post-ERCP-related pain was diagnosed when the patient presented with abdominal pain within 24 hours following ERCP, with pancreatitis and perforation being ruled out. Intolerance to sedation was defined when the procedure had to be discontinued within five minutes after initiation. Cardiopulmonary complications were present when the patient had a decrease in blood saturation levels that required discontinuation, angina or arrhythmias. Re-intervention was defined when the patient required a new procedure to resolve the initial indication, and failed ERCP when the opacification with contrast medium of the indicated duct was not achieved, or the clinical indication for the procedure remained unsolved. The mortality rate accountable to the procedure was defined as death occurring as a consequence of a complication. When there were doubts as to the actual cause of death the case was discussed with the professors and residents in the service, to define it as directly related, possibly related, or unrelated to ERCP.

Quantitative variables were analyzed by calculating the median and standard deviation values, and qualitative variables were described using proportions. A bivariate chi-square analysis was performed to explore possible associations between independent variables and complications.

The ethics committee authorized this trial because no interventions other than those already established were performed, and the information about the procedure and patient follow-up was collected in a confidential manner.

Results

A total of 381 patients were assessed, of which 9 (2.4%) were excluded for failing to achieve the required 1 month of follow-up (n = 8), for rendering unknown outcomes, or because the procedure was performed by an attached gastroenterology specialist (n = 1) without complications. Of the remaining patients (n = 372), 63.2% were intervened by one of the professors and 36.8% by the other professor. The overall features of the patients, and the indications for the procedures are described in table I.

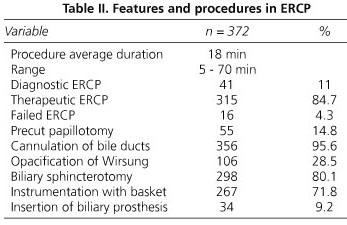

No ERCP was performed for the indication of cannulation of the pancreatic duct. It was observed that 8.6% of patients had previous precut papillotomy, sphincterotomy or sphincteroplasty. No patient had prior BII or Roux-en-Y reconstruction after gastrectomy. The overall success was 79.6%. ERCP findings and interventions are described in table II.

The majority of complications in 22 patients (76%) were diagnosed during the first evaluation carried out 4 hours after the procedure, 5 (17%) were diagnosed during the evaluation performed after 24 hours, and only 2 (7%) at the 48 hours evaluation. A total number of 29 patients (7.8%) presented with complications. Details on procedure complications are shown in table III.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis was present in 9 patients (2.4%). Symptoms occurred within the first 4 hours in 8 cases, particularly pain, which required amylase measurement and an abdominal X-ray. No patient died for this reason. It was mild in 3 patients, moderate in 5, and severe in 1, who required a surgical procedure.

Hemorrhage occurred in 5 patients (1.3%). One outpatient was diagnosed 48 hours later and only required a transfusion. The other 4 were diagnosed during the first 24 hours after the ERCP procedure and were handled with endoscopic injection at the bleeding site. One of these patients received plasma prior to the procedure due to anticoagulation treatment, and died as a result of this complication.

Perforation was present in 5 patients (1.3%). None of them underwent a precut papillotomy, two had prior sphincterotomies, which were enlarged, three had normal bile ducts, and bile duct cannulation was achieved in all of them. None had an intra or peri-diverticular papilla. One patient died due to this complication. No perforation was identified during the procedure or was caused by the duodenoscope at a site other than the major papilla.

Cholangitis occurred in 5 patients (1.3%). Cannulation and derivation of bile ducts was achieved in 4 patients and failed in one. Two cases were mild, two were moderate and one was severe, causing death. It must be noted that none of the patients had a tumor of the biliopancreatic confluence, nor died for this reason. These patients were evaluated independently from those with a tumor and cholangitis who died.

ERCP-related pain was present in one patient (0.3%) in whom perforation or pancreatitis were ruled out. This patient did not undergo precut or opacification with contrast medium of the Wirsung duct. Bile ducts were dilated and the patient required 4-day hospitalization.

Cardiopulmonary complications occurred in two cases (0.5%). One had acute atrial fibrillation and required 4 days' management. Another patient developed pulmonary edema.

The procedure could not be performed in two patients due to intolerance to sedation. One of them had to undergo a second intervention under general anesthesia, with no complications. The other patient was taken to the operation room without complications. No other complications such as basket impaction, allergic reactions or sedation-related respiratory depression were present in this series.

A second intervention was performed in 31 (8.3%) patients, 17 (4.5%) within the first 30 days and 14 after day 30. The mean time between the first and second procedures was 63 days (1 - 368). Complications arose in three patients: atrial fibrilation in one patient, cholangitis requiring percutaneous derivation in another patient, and another one developed hemorrhage, requiring suspension of the procedure. Cannulation of the bile ducts failed in 6 patients, and 4 were only diagnostic procedures.

There were 16 (4.3%) failed ERCP procedures, despite the fact that 10 of them underwent precut papillotomy. Six patients required a second intervention and two had complications: one suffered severe pancreatitis requiring a 14-day hospital stay, and the other one presented with cholangitis. In this patient bile duct cannulation failed, and the patient died due to a procedure-related cause.

Twenty-nine (7.8%) patients died during the follow-up period, 11 of them had neoplasms of the biliopancreatic tree, 2 had a Klatskin tumor, 3 had gallbladder cancer, 12 had choledocholithiasis, and 1 pancreatitis. An analysis of these cases was sub-classified as death unrelated to the procedure in 22 patients (myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism and cerebrovascular disease), possibly related to the procedure (4 patients) and directly related to or attributable to the procedure (3 patients). Consequently, the mortality rate attributable to the procedure in our series was 0.8%, even though, if for discussion purposes we include patients with prior cholangitis aggravated by the ERCP procedure, our mortality rate would increase to 1.6% (Table IV).

A bivariate statistical analysis demonstrated a significant difference in age and gender variables for pancreatitis, gender for perforation and for second interventions, bile duct diameter and time of procedure. No statistically significant variables were found for hemorrhage, cholangitis or ERCP-related pain (Table V).

Discussion

As reported by various prospective series, ERCP carries a significant risk of complications (6,7,10-24). A 1-month follow-up was achieved in 97% of our patients. The present study evaluated the diverse complications of ERCP adding quality indicators such as duration of procedure, failed ERCP procedures, and second interventions. No report specifically analyzing the duration of the procedures was found in the literature review. However, this may be significant for in this series the number of prolonged procedures (lasting 30 minutes or more) was 46 (12%), and of these, two patients died due to complications (cholangitis and perforation). Christensen et al. (7) reported the use of high doses of antispasmodic drugs as an indirect risk factor for cardiopulmonary complications perhaps due to the extended duration of the procedures.

Age was the only factor correlated with cardiopulmonary complications in this study, in patients aged 70 or more; and pancreatitis may be predicted in young females. This is consistent with reports from other series (8,11). Other authors found no significant differences with the use of ERCP in older patients (25).

Diagnostic procedures performed in this series were low (11%) compared with other series (7,11,18), 9% of these patients required a second intervention and 4.8% presented with complications (cholangitis and pancreatitis). These data, although lower than the 17% reported by García-Cano Lizcano (26), led us to reflect on the diagnostic use of ERCP, especially since, in our series, a significant number of patients required a second intervention. The small percentage of diagnostic procedures is attributable to the use of institutional guidelines, which indicate the use of ERCP in an appropriate clinical setting when patients meet two or more of the following criteria: elevated alkaline phosphatase, direct hyperbilirubinemia, dilated bile ducts or pancreatitis possibly due to bile pathogenesis. Thus the therapeutic intention of the procedures is high as suggested by the global trend (5).

Precut was required in 55 patients (14.8%) and success attributable to the procedure was 85%. No patient suffered a perforation but three of them developed pancreatitis (5.4%). However, no statistically significant difference was observed (p = 0.11). This percentage of complications due to precut is similar to what is reported by other authors, who encountered 4.2% complications and a 75% success in using it (11,17). Among the 80% of patients who underwent biliary sphincterotomy, 13% presented with complications, a higher figure than reported in other trials (11,17,18), with this series not providing an explanation for this finding.

Non-intentional Wirsung opacification with contrast medium was done in 28.5% of the patients, of which 12% required a second intervention, 11% had complications, one of them fatal, and 77% evolved without complications. It should be noted that only one case of mild pancreatitis occurred in these patients. No pancreatic prosthesis was used to prevent pancreatitis because this measure is not fully accepted as a protection factor for this condition, and rather increases the costs of the procedure. The Loperfido (11) series shows a smaller percentage of Wirsung opacifications but does not report any complication secondary to pancreatography.

The Cotton international complication grading scale was used in this report. ERCP-related pancreatitis was present in 2.4% of participants. Most of them were considered mild to moderate and only one was considered severe. Precut, biliary sphincterotomy, normal bile ducts, Oddi dysfunction and young healthy females have been related to this complication (6,7,10,11,13,19,21,23). In this series, females aged less than 37 had a higher risk of pancreatitis.

ERCP-related biliary sepsis is reported in up to 3%. The proportion was 1.3% in our study, and a bile duct bypass was performed in all cases except for one. If we included patients with tumors of the biliopancreatic confluence we would have a total of 2.6% for cholangitis. The identified risk factors include biliary stasis, malignant obstruction, and the use of precut (7,22-24). The administration of prophylactic antibiotics is still controversial (21,22). We did not use a routine prophylactic antibiotic regimen prior to ERCP. It was only used in patients with suspected cholangitis.

Hemorrhage occurred in 5 patients (1.3%), reflecting a very similar percentage to that reported by other authors (7,10,11). Bleeding was only diagnosed in one patient in a delayed manner. The other four patients were diagnosed in a timely manner by means of an endoscopic intervention, attributable to the definition of the variable: hemorrhage. The use of precut, sphincterotomy, duodenal diverticula, prior anticoagulation treatment, and the administration of plasma have been deemed risk factors for this event (7,9,15,21,22). None of these factors was encountered in this study. Only intra-operative bleeding became a common factor without reaching statistical significance.

Perforation occurred in 1.3% of patients, and this is similar to what is reported in other trials (7,17,20,22). Diverticula, precut and inexperience have been identified as risk factors (7,12,15,17,20). Perforation was never diagnosed late in this series. However, one patient died due to this cause. Precut was not performed in any patient but biliary prosthesis insertion was performed. These are described by various authors as predisposing risk factors for this condition (11,16, 17,20,21).

There is no analysis of complications describing a difference between inpatients and outpatients (16) in the reviewed series. In this study 38.7% were outpatients and 61.3% inpatients. Pancreatitis, perforation and cholangitis occurred more commonly in outpatients, and we did not find any factors to explain this result. Cardiopulmonary events occurred only in inpatients, which could be explained by inpatient-associated comorbidities.

The mortality rate in our study was 7.8%. Of the 29 patients who died within 30 days following the ERCP procedure 16 had a terminal malignant condition and only 13 a benign condition.

ERCP efficacy is determined by a high success level with a low frequency of complications (22). Most of the studies used to consider an ERCP to be successful if cannulation of the indicated duct was achieved; however, the current trend encourages reporting all the adverse events of a procedure. The proportion of bile duct cannulations in this trial was 95.6%, much greater than that expected for training centers (80%) (22). Precut was used in 14.8% of participants, similar to the percentage accepted for referral centers (10 to 15%) (22).

The incidence of a second intervention due to residual stones after ERCP was 8.3%, much less than the 15% accepted for general centers (22,24). Apparently, the use of Vater papillary balloon dilation could decrease the proportion of residual stones (27,28). It must be noted at this point that literature does not describe a theoretical approach to ERCP - related residual choledocholithiasis as that used after a cholecystectomy, which also considers the time between the ERCP procedure and cholecystectomy. The percentage of failed procedures was 4.3%, much less than the 10% proposed for centers which perform standard ERCPs (15,22). However, although success was achieved in 79% in this series we consider it to be less because some second interventions could have been conducted in another institution and not within the estimated follow-up period.

In conclusion, it is confirmed that ERCP complications relate to the therapeutic intention of this procedure. Moreover, it highlights the importance of an expeditious communication between the physician who perform the procedure and the patient to detect the maximum number of secondary adverse events related to the procedure in a timely manner. The creation of centers of excellence would improve the efficacy of the procedure.

Aknowledgements

Dr. Raúl Piña Téllez, Assistant Professor of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy; Dr. Jesús Díaz Realpe, Resident of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy; Dr. José Chaves Chamorro, Resident of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy; Dr. Juan Lara Ustariz, Resident of Gastrointestinal Surgery and Digestive Endoscopy (PUJ); Mrs. Miryam Millán, Licensed nurse of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy at San José Hospital, Bogotá.

References

1. McCune W, Shorb P, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of Vater: a preliminary report. Ann Surg 1968; 167: 752-6. [ Links ]

2. Soehendra N, Reynders-Frederix V. Palliative gallengang-drainage. Deutsch Med Wochenschr 1979; 104: 206-9. [ Links ]

3. Peñaloza-Rosas A. Cincuentenario de una escuela de Gastroenterología. Medicina (Academia Nacional de Medicina de Colombia) 2002; 24: 124-31. [ Links ]

4. Peñaloza-Ramírez A, Rodríguez-Rubiano C, Mozo-Ortiz J, Aponte-Ordoñez P. Manejo endoscópico de fístulas pancreáticas. Reporte de dos casos. Rev Colomb Cir 2007; 22: 27-32. [ Links ]

5. Prat F, Amouyal G, Amouyal P, Pelletier G, Fritsch J, Choury AD, et al. Prospective controlled study of endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in patients with suspected common-bile duct lithiasis. Lancet 1996; 347: 75-9. [ Links ]

6. Freeman M. Adverse events and success of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56(Supl. 6): 273-82. [ Links ]

7. Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 60: 721-31. [ Links ]

8. Fisher L, Fisher A, Thomson A. Cardiopulmonary complications of ERCP in older patients. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63: 948-55. [ Links ]

9. Baillie J. Complications of ERCP. En: Jacobson I. ERCP and its applications. 1st ed. Philadelphia-New York: Lippincot-Raven Publishers; 1998. p. 37-54. [ Links ]

10. Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, et al. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 417-23. [ Links ]

11. Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilou F, Coston F, De Berardinis F, et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48: 1-10. [ Links ]

12. Aronson N, Flamm C, Bohn R, Mark D, Speroff T. Evidence-based assessment: patient, procedure or operator factors associated with ERCP complications. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56(6 Supl.): 294-302. [ Links ]

13. Vandervoort J, Soetikno R, Tham T, Wong R, Ferrari A, Montes H, et al. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 652-6. [ Links ]

14. Nelson D, Freeman M. Major hemorrhage from endoscopic sphincterotomy: risk factor analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1994; 19: 283-7. [ Links ]

15. Schutz S, Abbott R. Grading ERCPs by degree of difficulty: a new concept to produce more meaningful outcome data. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 535-9. [ Links ]

16. Mahnke D, Chen Y, Antillon M, Brown W, Mattison R, Shah R. A prospective study of complications of endoscopic retrograde colangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound in an ambulatory endoscopic center. Clinical Gastroenterol and Hepatol 2006; 4: 924-30. [ Links ]

17. Tang S, Haber G, Kortan P, Zanati S, Cirocco M, Ennis M, et al. Precut papillotomy versus persistence in difficult biliary cannulation: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy 2005; 37: 58-65. [ Links ]

18. Trap R, Adamsen S, Hart-Hansen O, Henriksen M. Several and fatal complications after diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective series of claims to insurance covering public hospitals. Endoscopy 1999; 31: 125-30. [ Links ]

19. Barhet M, Lesavre N, Desjeux A, Gasmi M, Berthezene P, Berdah S. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy: results from a single tertiary referral center. Endoscopy 2002; 34: 991-7. [ Links ]

20. Kayhan B, Akdogan M, Sahin B. ERCP subsequent to retroperitoneal perforation caused by endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 60: 833-5. [ Links ]

21. Rochester J, Jaffe D. Minimizing complications in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2007; 17: 105-27. [ Links ]

22. Baron T, Petersen B, Mergener K, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal S, et al. Quality indicators for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63(4 Supl.): 29-34. [ Links ]

23. Baley A, Bourke M, Williams S, Walsh P, Murray M, Lee E, et al. A prospective randomized trial of cannulation technique in ERCP: effects on technical success and post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy 2008; 40: 296-301. [ Links ]

24. Freeman M. Adverse outcomes of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: avoidance and management. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2003; 13: 775-98. [ Links ]

25. García-Cano J, González-Martín J, Morillas-Ariño J, Pérez- García J, Redondo-Cerezo E, Jimeno-Ayllon C, et al. Resultados del drenaje de la vía biliar por CPRE en pacientes en edad geriátrica. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007; 99: 453-6. [ Links ]

26. García-Cano Lizcano J, González-Martín J, Morillas-Ariño J, Pérez-Sola A. Complicaciones de la colangiopancreatografia retrograda endoscópica: estudio en una unidad pequeña de CPRE. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 163-73. [ Links ]

27. Espinel J, Pinedo E, Olcoz JL. Balón hidrostático de gran diámetro en coledocolitiasis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007; 99: 33-8. [ Links ]

28. Espinel J, Pinedo E. Dilatación de la papila de Vater con balón de gran diámetro para la extracción de coledocolitiasis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100: 632-6. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A. Peñaloza-Ramírez.

Calle 118 No. 12-25 (apto 302). Bogotá, Colombia.

e-mails: apenaloza@fucsalud.edu.co;

carlosleal73@gmail.com

Received: 02-02-09.

Accepted: 07-07-09.

text in

text in