My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.102 n.2 Madrid Feb. 2010

A retrospective study of pediatric endoscopy as performed in an adult endoscopy unit

Estudio retrospectivo sobre la endoscopia pediátrica desarrollada en un servicio de endoscopias de adultos

L. Julián-Gómez1, J. Barrio1, R. Izquierdo2, P. Gil-Simón1, S. Gómez de la Cuesta1, R. Atienza1, C. de la Serna1, M. Pérez-Miranda1, P. Fernández-Orcajo1, C. Alcalde2 and A. Caro-Patón1

Services of 1Digestive Diseases and 2Pediatrics. University Hospital Río Hortega. Valladolid, Spain

ABSTRACT

Gastrointestinal endoscopy is a safe, efficient technique with minimal complications, and a useful diagnostic tool for the pediatric population. Under ideal conditions endoscopies for children should be performed by experienced pediatric endoscopists. In this study we report our experience with pediatric endoscopy at the general adult endoscopy unit in our hospital. Our goal is to quantify the number of endoscopies performed in children, as well as their indications and findings, the type of sedation or anesthesia used, and the time waiting for the test to occur. Our experience demonstrates that endoscopists in a general adult gastroenterology department, working together with pediatricians, may perform a relevant number of endoscopies in children in a fast, safe, effective manner.

Key words: Pediatric endoscopy. Celiac disease. Sedation. Pediatric endoscopist.

RESUMEN

La endoscopia gastrointestinal es una técnica segura y eficiente con mínimas complicaciones, así como una útil herramienta diagnóstica en la población pediátrica. En condiciones ideales, las endoscopias en niños deberían ser realizadas por endoscopistas pediátricos experimentados. En este estudio reportamos nuestra experiencia en la realización de endoscopias pediátricas en la Unidad de Endoscopias general de adultos de nuestro hospital.

El objetivo es cuantificar la cantidad de endoscopias realizadas en niños, así como las indicaciones y hallazgos de las mismas, el tipo de sedación o anestesia empleado y el tiempo de espera para la realización de la prueba. Nuestra experiencia demuestra que los endoscopistas de un servicio de gastroenterología general de adultos, en colaboración con pediatras, pueden realizar un número importante de endoscopias a niños, de forma rápida, segura y eficaz.

Palabras clave: Endoscopia pediátrica. Enfermedad celiaca. Sedación. Endoscopista pediátrico.

Introduction

Endoscopy is a useful diagnostic, follow-up, and therapeutic tool for both the pediatric and adult populations (1), and represents a simple, low-risk study that allows adequate management for gastrointestinal disease (2).

Under ideal conditions, pediatric endoscopies should be performed by experienced pediatric endoscopists; however, for most patients, as referral to a site with a pediatric dept. including a pediatric endoscopy unit with expertise is challenging and requires wait time, endoscopists at the general gastroenterology dept., working together with pediatricians, eventually perform a high number of endoscopic procedures in children (3).

Our goal was to carry out a retrospective study of pediatric endoscopies performed over 3 years in our gastroenterology dept. endoscopy unit, including sedation type, indications, findings, referral sources, and time elapsed from referral to procedure.

Material and methods

Using our hospital's endoscopy unit's database (Endobase, Olympus. Japan), endoscopies performed from July 2005 to July 2008 were reviewed, and those carried out in children 15 years of age or younger were selected, bearing in mind that not all pediatric endoscopies ordered by the pediatrics dept. were carried out in our unit, but a small number were performed by pediatric gastroenterologists in another referral hospital as will be seen below.

Upper digestive endoscopy (UDE) was performed with a thin GIF-H180 endoscope (Olympus. Japan) 9.8 mm in external diameter and fitted with a 2.8-mm work channel, and colonoscopy (and terminal ileoscopy in some cases) using a pediatric PCF-140L (Olympus. Japan) colonoscope 11.3 mm in diameter and fitted with a 3.2-mm channel, or a CF H180AL colonoscope (Olympus. Japan) 12.8 mm in diameter and with a 3.7-mm work channel.

In children up to 35 kg of body weight colonoscopy was carried out with a pediatric colonoscope, and an adult colonoscope (over 12 mm in diameter) was used for those with a higher weight.

Preparation for gastroscopy included 7-8 hours fasting; preparation for colonoscopy consisted of 8-10 sachets with the osmotic laxative macrogol 400 mixed with electrolytes (Solución Evacuante de Bohm, Laboratorios Bohm. España) 5 hours before the study according to patient age, weight, and stool consistency and number.

The following parameters were analyzed: number of performed endoscopies, number of children examined, patient gender and age, sedation used, study indications, endoscopic findings, source of referral, and time elapsed from order to procedure.

Results

A total of 19,299 endoscopies were performed during the study period of 3 years, and 51 (0.26%) of them were carried out in 42 children (28 boys and 14 girls) from 3 to 15 years of age (mean 12 years). All children undergoing endoscopy weighed above 15 kg.

Indications

Indications for referral included diarrhea, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, weight loss, and suspected flare in a patient diagnosed with IBD for colonoscopy, and foreign body extraction, caustic ingestion, duodenal biopsy collection, suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), upper abdominal discomfort, dysphagia, and PEG regarding UDE.

Endoscopic findings

In all, 26 UDE procedures were carried out for 24 children (15 boys and 9 girls) with ages between 3 and 15 years.

Endoscopic findings and/or required therapy included: foreign body extraction in 8 UDE procedures (30.7%), hiatal hernia (HH) and/or distal esophagitis in 4 (15.4%), caustic-related injury in 4 (15.4%), PEG catheter positioning in 2 (7.7%), and UGIB from PEG in 1 (3.8%). The examination was normal with no intervention in 7 cases (27%).

On the other hand, a total of 25 colonoscopies were carried out in 20 children (14 boys and 6 girls) with ages between 6 and 14 years.

Endoscopic findings included: inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in 12 children (60%) (in 7 children the diagnosis was ulcerative colitis, in 5 Crohn's disease), nonspecific colitis in 2 children (10%), and juvenile polyp excised in 1 patient (5%). The exam was consistent with normality in 5 explored children (25%).

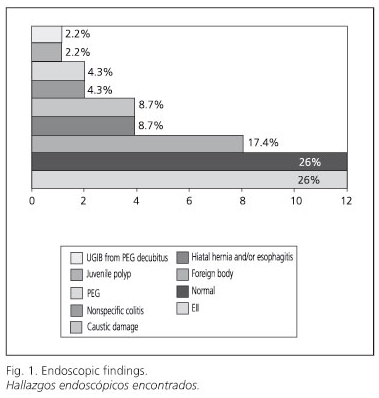

Most common findings during endoscopy (UDE and colonoscopies) included (Fig. 1): IBD (26%), normal exam (26%), and foreign body extraction (17.4%).

Sedation

All exams were performed with sedation. In 34 children (78.6%), sedation was conscious; it was applied at the digestive endoscopy unit and performed by pediatric staff for over 80% of subjects, with the rest (usually children older than 12-13 years), being carried out by general endoscopists.

When sedation was performed at the endoscopy unit patients received oxygen therapy through nasal specs, and pulmonary and cardiac function was monitored constantly. Importantly, none of the explored children had significant comorbidity associated.

Sedation consisted of midazolam up to 5 mg (maximum dose) for UDE, and additionally with Dolantine up to 50 mg for colonoscopy, with dosage according to age, tolerability, and patient body weight.

Only in 8 children (19%) the exploration was performed in an operating room under general anesthesia, in 6 cases (75%) for foreign body extraction from the upper digestive tract thus securing the airway. All 8 children where the exploration was performed under general anesthesia were 8 years or younger and general anesthesia was used for 80% of children (8 of 10 children) with 8 years of age or younger.

Order source and wait time for procedures

Examination orders had the following sources: Pediatrics, 66.6% (34: 15 of which were ordered by emergency pediatricians as UDEs, and 19 were scheduled for inpatients), Gastroenterology, 25.4% (13: 9 for inpatients and 4 for outpatients, none of them with urgency), Intensive Care Unit (ICU), 4% (2 via urgent orders), Family Medicine (Primary Care may freely order endoscopies), 2% (1 non-urgent order), General Emergency Room, Adults, 2% (1 urgent order) (Fig. 2). Endoscopies ordered urgently totaled 18 (35.2%), and all were performed within 14 hours; orders for inpatients totaled 28 (55%), and were processed within 72 hours; orders for outpatients (gastroenterologists and family physicians) totaled 5 (9.8%), and were accomplished within 1-2 months (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The present study shows our experience with pediatric endoscopy at the general adult endoscopy unit in our hospital, which lacks a pediatric surgery department. In a study by Elías Pollina J et al. (4), which surveyed 24 hospitals at all levels with a pediatric surgery dept., pediatric surgeons were shown to perform 43.8% of all pediatric GI endoscopies (75.7% of UDEs, 24.2% of colonoscopies), with the remaining exams being shared with pediatricians and general gastroenterologists; they concluded that in bigger centers with highly developed endoscopy units pediatric surgeons performed fewer endoscopies as compared to other sites, and highlighted that nearly 90% of interventionist endoscopies (PEG, dilation) are carried out by pediatric surgeons, except for endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), which is performed by general adult endoscopists given that it is a rare study in children and the existing learning curve results in complications. Regarding who should perform endoscopies, the training curriculum for pediatric surgery residents clearly establishes that the latter must have completed a given number of endoscopic examinations at training completion, which is not the case for pediatrics training programs.

The indication for endoscopy in our center was carefully considered for each child, and most procedures were performed by pediatric gastroenterologists followed by adult gastroenterologists, which is consistent with a study reported by Hayat et al. (3) analyzing pediatric endoscopies in an adult gastroenterology department. Indications for these explorations are usually consistent with those reported in other papers (3,5), with foreign body extraction, caustic ingestion, and duodenal biopsy collection being most common for UDE, and abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, or suspected IBD flare-up for colonoscopy. Despite careful indication selection, endoscopy was normal (i.e., with no endoscopic and/or histological changes in biopsy samples) for 27% of UDEs and 25% of colonoscopies, which represents a lower percentage when compared to a North American series (6) where 44% of UDEs and 41% of colonoscopies yielded normal findings, and a pediatric Australian series (7) where 48% of UDEs were normal. Endoscopic procedures with a normal result in our series totaled 23.5%, which is almost half the number in the study by Hayat et al. (3) - 52%. A point that may help support this clear difference in percentages across papers is perhaps a higher number of explorations in the above-quoted studies. In our series, orders including duodenal biopsy collection does not surprisingly reach 20% (15.3%), whereas in the series by Hayat et al. (3) such orders amounted to nearly 50% in the case of UDE, and celiac disease (CE) was diagnosed in over 85% of subjects; in our series no histological studies has intestinal atrophy. An explanation is that almost 71% of UDE orders were filled by pediatricians -who ordered duodenal biopsy collection in only 2 (11.7%)- and not all pediatric endoscopies ordered to rule out celiac disease by the pediatrics dept. were performed in our unit -a small percentage were referred to another hospital with a pediatric gastroenterology unit where pediatric gastroenterologists perform GI endoscopies, and yet another percentage had duodenal samples obtained using a Crosby's capsule.

As regards sedation, in the series by Hayat et al. (3) 38.5% of studies were carried out under general anesthesia, and 4.3% had no sedation whatsoever, which is in contrast with our series where, regardless of age, sedation was used for all procedures and only 19% were carried out in an operation theater under general anesthesia. Despite all this, the use of i.v. sedation or general anesthesia is highly variable in pediatric endoscopic procedures. Given that desaturations have been described in children during endoscopy with i.v. sedation (5,8-10) some specialists are in for general anesthesia (11,12). These studies advocate for general anesthesia in children under 11 years of age, and general anesthesia or i.v. sedation in those older than this. However, several studies have shown that conscious i.v. sedation is safe at an endoscopy unit (5,13,14). In our study, children 11 years or younger totaled 14 (77%), and general anesthesia was used for 8 of them (57.1%); these 8 children were 8 years old or younger, which is in contrast with the series by Hayat et al. (3), where sedation was applied in an operating room under general anesthesia for 89% of children younger than 11 years. The use of general anesthesia and propofol is seemingly increasing in pediatric endoscopy units, usually based on patient age, anticipated intolerance to the procedure, study complexity, specialist preferences, or patient comorbidity (15). Propofol has been said to potentially increase efficiency in an endoscopy unit as it reduces time from sedation onset to sedation recovery. However, a prospective study by Lightdale et al. (16) demonstrated that sedation with propofol allowed no shorter endoscopic procedures in children, that sedation with midazolam and fentanyl, while inducing an earlier sedation onset, exhibited a longer period until patient recovery. Prospective studies have shown their matching effectiveness and safety, but a lower cost for a rigorously standardized sedation procedure versus general anesthesia regarding endoscopies in children of all age groups (13). Since it is a minimally invasive procedure with a low complication incidence in the pediatric population, endoscopy is deemed a safe technique (2,6). Given that endoscopies are ever increasing in numbers and complexity with the introduction of therapeutic modalities, additional complications may develop ranging from mild benign issues to life-threatening events (2,17,18). Both in our series and in that reported by Hayat et al. (3) no endoscopic complications arose. In the study by Iqbal et al. (2), including 3,269 colonoscopies in children, perforation had an incidence of 0.09%; on the other hand, the rate of complications after 9308 gastroscopies was 0.06%, with iatrogeny having a wider spectrum (bleeding, perforation, mucosal tear). Data from this study seem consistent with those reported for both adult and pediatric patients elsewhere (2,17-20). There is no single standard regimen for colon cleansing prior to pediatric colonoscopy; in fact, it varies according to site and ordering doctor. Various colon-cleansing solutions for adults are known to be inappropriate for children because of poor palatability and high volume. Fluid ingestion the day before the procedure, and a saline enema may suffice for smaller children with normal or abundant stool production (21). Various regimens have been reported for colon preparation in pediatric patients, including polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 for 4 days at a dose of 1.5 g/kg/d, also limiting fluid ingestion on the fourth day (22), or Fleet Fosfosoda 22.5 ml if body weight is lower than 30 kg or 45 ml for weights above 30 kg both in the morning and in the evening, including fluids the day before the procedure (23).

Finally, in view of the data found in our study, we may conclude that, given the excellent tolerability and safety of pediatric endoscopy as performed by gastroenterologists, the screening of celiac disease in at-risk groups should be an additional indication. Endoscopists in an adult gastroenterology department, working together with pediatricians, may carry out a significant number of endoscopic procedures in children in a rapid, safe, effective manner.

References

1. Fox VL. Pediatric endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2000; 10: 175-94. [ Links ]

2. Iqbal CW, Chun YS, Farley DR. Colonoscopic perforations: a retrospective review. J Gastrointest Surg 2005; 9: 1229-36. [ Links ]

3. Hayat J, Sirohi R, Gorard D. Paediatric endoscopy performed by adult-service gastroenterologist. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 20: 648-52. [ Links ]

4. Elías Pollina J, Esteban Ibarz JA, González Martínez-Pardo N, Ruiz de Temiño Bravo, Escartín Villacampa MR. Endoscopia: estado actual. Cir Pediatr 2007; 20: 29-32. [ Links ]

5. Balsells F, Wyllie R, Kay M, Steffen R. Use of conscious sedation for lower and upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations in children, adolescents, and young adults: a twelve-year review. Gastrointest Endosc 1997; 45: 375-80. [ Links ]

6. Gilger MA, Gold BD. Pediatric endoscopy: new information from the PEDS-CORI project. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2005; 7: 234-9. [ Links ]

7. O'Loughlin EV, Dutt S, Kamath R, Gaskin K, Dorney S. Prospective peer-review audit of paediatric upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Paediatr Child Health 2007; 43: 551-4. [ Links ]

8. Casteel HB, Fiedored SC, Kiel EA. Arterial blood oxygen desaturation in infants and children during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1990; 36: 489-93. [ Links ]

9. Bendig DW. Pulse oximetry and upper intestinal endoscopy in infants and children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1991; 12: 39-43. [ Links ]

10. Gilger MA, Jeiven SD, Barrish JO, McCarroll LR. Oxygen desaturation and cardiac arrhythmias in children during esophagogastroduodenoscopy using conscious sedation, Gastrointest Endosc 1993; 39: 392-5. [ Links ]

11. Stringer MD, McHugh PJ. Monidtoring during endoscopy. Paediatric endoscopy should be carried out under general anaesthesia. Brit Med J 1995; 311: 452-3. [ Links ]

12. Lamireau T, Dubreuil M, Daconceicao M. Oxygen saturation during esophagogastroduodenoscopy in children: general anesthesia versus intravenous sedation. J Pediatr Gastroentgerol Nutr 1998; 27: 172-5. [ Links ]

13. Squires RH, Morriss F, Schluterman S, Drews B, Galyen L, Brown KO. Efficacy, safety, and cost of intravenous sedation versus general anesthesia in children undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 41: 99-104. [ Links ]

14. Mamula P, Markowitz JE, Neiswender K, Zimmerman A, Wood S, Garofolo M, et al. Safety of intravenous midazolam and fentanyl for pediatric Gl endoscopy: prospective study of 1578 endoscopies, Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65: 203-10. [ Links ]

15. Koh JL, Black DD Leatherman LK Harrison RD, Schmitz ML. Experience with an anaesthesiologist intervention model for endoscopy in a pediatric hospital. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001; 33: 314-8. [ Links ]

16. Lightdale J, Valim C, Newburg A, Mahoney L, Zgleszewski S, Fox V. Efficiency of propofol versus midazolam and fentanyl sedation at a pediatric teaching hospital: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 67: 1067-75. [ Links ]

17. Farley DR, Bannon MP, Zietlow SP, Pemberton JH, Ilstrup DM, Larson DR. Management of colonoscopic perforations. Mayo Clin Proc 1997; 72: 729-33. [ Links ]

18. Fatima J, Baron TH, Topazian MD, Houghton SG, Iqbal CW, Ott BJ, et al. Pancreticobiliary and duodenal perforations after periampullary endoscopic procedures. Arch Surg 2007; 142: 448-55. [ Links ]

19. Darbari A, Kalloo AN, Cuffari C. Diagnostic yield, safety, and efficacy of push enteroscopy in pediatrics. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 64: 224-8. [ Links ]

20. Zahavi I, Arnon R, Ovadia B, Rosenbach Y, Hirsch A, Dinari G. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in pediatric patient. Isr J Med Sci 1994; 30: 664-7. [ Links ]

21. Fox VL. Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. In: Walker WA, Durie PR, Hamilton JR, et al., editors. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease. Hamilton (ON), Canada: Decker BC; 2000. p. 1415. [ Links ]

22. Pashankar DS, Uc A, Bishop WP. Polyethylene glycol 3350 without electrolytes: a new safe, effective, and palatable bowel preparation for colonoscopy in children. J Pediatr 2004; 144: 358-62. [ Links ]

23. El-Baba MF, Padilla M, Houston C, Madani S, Lin CH, Thomas R, T et al. A prospective study comparing oral sodium phosphate solution to a bowel cleansing preparation with nutrition food package in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006; 42: 174-7. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Laura Julián Gómez.

Servicio de Aparato Digestivo.

Hospital Universitario Río Hortega.

C/ Rondilla de Santa Teresa, s/n.

47010 Valladolid, Spain.

e-mail: laurahjgo@hotmail.com

Received: 18-08-09.

Accepted: 21-10-09.

text in

text in