My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.102 n.2 Madrid Feb. 2010

Clinical practice guidelines for managing coagulation in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures

Guía de práctica clínica para el manejo de la coagulación en pacientes sometidos a técnicas endoscópicas

F. Alberca-de-las-Parras

Service of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca. Murcia, Spain

Why is there a need to create guidelines related to problems in coagulation and conducting endoscopic procedures?

For many years, anti-coagulants and single or double anti-platelet agents have become a therapeutic and preventative arm particularly in high-prevalence cardiovascular pathologies. This fact, combined with the increase in endoscopic techniques suggests an increased risk.

However, the risk is not only a precursor to potential haemorrhage, but to a potential risk of thrombosis (1) as well, hence the endoscopists should not overlook these possible risks.

An effort must be made to jointly collect criteria based on published scientific literature. Other associations have already initiated efforts towards accomplishing this task (2-4) and secondary benefits have even been demonstrated in both cost-effectiveness as well as having zero impact on the incidents of thrombosis in implementing these guidelines (5).

What attitude should be taken when faced with the utilization of anticoagulants, anti-platelet agents or nsaids in patients with gastrointestinal haemorrhage? (Fig. 1)

Anticoagulants must be discontinued immediately and the following therapeutic measures can be initiated in a sequential manner and concurrently with endoscopic techniques (3,6).

1. Vitamin K1, i.v. (phytomenadione), 10 mg (one ampoule) mixed in 100 ml of 0.9% normal saline or 5% glucose solution: 10 ml over 10 minutes (1 mg/10 min) and afterwards, the remaining solution over 30 minutes. Its effect is not immediate and lasts over approximately 8 hours.

2. Fresh frozen plasma, 10 to 30 ml/kg; at 6 hours, half the dose can be repeated as the half-life of the factors is 5 to 8 hours.

3. Prothrombin complex concentrate combined with factor IX (Prothromplex Immuno TIM 4600 I.U®): Equivalent to 500 ml of plasma. Dosage: (required-obtained prothrombin time) x weight in kg x 0.6.

4. Activated recombinant factor VII: 80 μg/kg per slow i.v. bolus (2 ml amp = 1.2 mg).

-Effect takes place within 10 to 30 minutes after administration.

-The effect lasts up to 12 hours.

-It should not be combined with prothrombin complexes.

-It adjusts prothrombin time and corrects platelet function defects.

These mechanisms will be utilised until the INR stabilizes between 1.5 and 2.5 and the bleeding stops. Anticoagulants are resumed 3-5 days later once we have ensured that the risks have diminished (performed a second-look endoscopy).

Recently, an abstract was presented which demonstrated that the risk of bleeding in patients who are prescribed anticoagulants is 6.5 times higher than in those who do not take these medications (7).

Suspending anti-platelet agents and NSAIDs does not alter the natural course of the process because its effect on coagulation will only be delayed for a few days, although it must be taken into consideration if the case consists of lesions that will not foreseeable heal quickly. Remember that aspirin and NSAIDs can be the cause itself of haemorrhage.

Should coagulation studies be carried out before performing endoscopic procedures?

There is no scientific evidence available to support this action. In a clinical guide published by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) (8), it was established that laboratory tests to detect unmanifested coagulation disorders was unuseful even for high-risk techniques, and is not indicated for routine pre-endoscopy testing. Furthermore, it raises legal questions regarding whether tests should be performed when a wrong interpretation of coagulation studies may lead to legal entanglements. Tests are never a substitute for a prior clinical history, and is only required if a disorder is suspected.

What coagulation disorders must be taken into consideration before performing endoscopic procedures?

For patients presenting with thrombocytopenia, the action to be taken depends upon the type of procedure.

-In high-risk procedures, platelet count must be higher than 50,000/μl.

-Low-risk endoscopic explorations may be carried out in patients with a platelet count > 20,000/μl.

Recommendation D

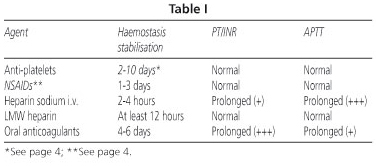

-Prothrombin activity: PT plasma levels less than 50% vs. INR > 1.5 suggests an increased risk of bleeding. The above-mentioned plasma levels are routinely found in patients with chronic hepatopathies and in those undergoing oral anticoagulant treatment (Table I).

-Alteration in activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT): it is considered a prolonged APTT with respect to normal APTT. This can be seen in the utilisation of heparin sodium IV.

How can these disorders be corrected before performing endoscopic procedures?

-Correcting platelet deficiency is carried out in a programmed manner by infusion during the course of the endoscopic procedure and in the immediate prior time span. Increasing the platelet count to between 40,000 and 50,000/mm3 is all that is required.

• Each unit of platelets increases the count by 5,000 to 10,000 per mm3.

• The dosage is 1 U/10 kg of body weight.

• In case of platelet refractoriness with manifestations of severe bleeding, activated recombinant factor VII is recommended (rVlla) (Novoseven©), which has a hemostatic effect in patients with severe thrombocytopenia and thrombocytopathies at a dosage of 90 to 150 μg/kg every two hours i.v. until bleeding is controlled. Due to a high cost, its prophylactic use must be limited to very specific and urgent cases.

-In the event of alterations in prothrombin time, the same guidelines mentioned above are also applicable to patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy.

Alterations in activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), such as in patients being treated with heparin sodium, usually revert to normal levels when medication is withdrawn within 4 to 6 hours. However, if in an emergency situation, a more rapid reversal is desired, protamine sulfate is the drug of choice; 1 mg neutralizes 100 units of heparin. It is administered in 100 ml of 0.9% normal saline in slow i.v. Do not administer a dose higher than 100 mg (2 ampoules), as high doses may produce an anticoagulant effect.

What endoscopic procedures are considered a major risk for bleeding?

The risk of bleeding appears to be defined by consensus and hence different clinical guidelines and manuals were established, suggesting two risk levels (Table II):

-Biopsies: the risk of haemorrhage in biopsies is approximately 1‰ (9).

-Polypectomy: the risk of major haemorrhage from polypectomy in various widespread series varies between 0.05 and 1%, and may even reach 4.3% in polyps larger than 1 cm, and 6.7% in those larger than 2 cm (10-12). This risk seems to increase with polyps larger than 2 cm, and pediculated polyps have been found to bleed more than sessile ones. Thus, combining the procedure with a technique that decreases the risk such as prophylactic adrenaline, an endo-loop or a single-use loop (11) is recommended for patients undergoing antiplatelet treatment.

There are two types of bleeding:

• Immediate, when nutrient vessels do not coagulate sufficiently.

• Delayed, between 1 and 14 days, but serious: It must be taken into consideration before reinitiating antiplatelet agents.

-ERCP and sphincterotomy: the incidence of haemorrhage is between 2.5 and 5% (13). Different studies define anticoagulation as a clear risk factor for bleeding. In terms of platelet antiaggregation only two retrospective studies (14,15) have analysed this effect with inconclusive results as the Clinical Guidelines of the American Society suggest, yet one of them demonstrates an acute risk for bleeding (14) at 9.7 vs. 3.9% (ASA vs. control, p < 0.001), and for delayed bleeding at 6.5 vs. 2.7% (p = 0.04), which suggests that, except for emergency situations, discontinuing the medication at least 7 days before the procedure is recommended. Balloon sphincteroplasty was proposed as an alternative technique in patients requiring an emergency opening of the bile duct who had coagulation disorders (16), as well as the use of temporary biliary prostheses without sphincterotomy.

-Enteroscopy: this simple technique does not suggest any risks, but if one approaches it as a therapeutic and interventional technique, the focus must be placed on considering the procedure a risk, as in up to 64% of cases it is performed as a therapeutic measure (17).

Are single or double antiplatelet agents a contraindication for any endoscopic technique?

There is no convincing data that will convert single antiaggregation into an absolute contraindication for any endoscopic technique to date.

In terms of double antiaggregation, there are no available studies about its effect, although in light of the existing data, it appears reasonable to attempt and avoid any procedures as long as this treatment is required, or low molecular weight heparin should be considered.

Is there any existing evidence about increased intestinal bleeding in patients undergoing antiplatelet therapy?

In a study in experimental animals where 7-mm lesions in the colon were induced, an increase in bleeding time was demonstrated in animals treated with aspirin versus the control group (155 vs. 169 seconds - p < 0.05) (18); in the same manner, an increase in bleeding at the biopsy suture site was also present in patients treated with aspirin versus NSAIDs or the control group (19).

Nevertheless, these experimental studies did not demonstrate any clinical impact on the literature when referring to its relevance in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures.

The Sociedad Española de Anestesiología y Reanimación [The Spanish Society of Anesthesiology and Recovery] have prepared joint recommendations prior to carrying out loco-regional and epidural aenesthesia with the following data (20,21) (Tables III and IV):

-Aspirin and NSAIDs have not demonstrated an increased risk of bleeding in case of in various studies that were carried out, although these studies were retrospective or limited in their analysis, and were the basis for the ASGE clinical guidelines which recommend withdrawing antiaggregants prior to endoscopic procedures (13,22-24).

However, in one of the prospective studies (22), while no increase in complications is seen, it does show bleeding traces in faeces in up to 6.3% of patients versus 2.1% in the placebo group. In a study on controlled cases (25), the most important complication, which is delayed bleeding, was specifically analysed, confirming that there is no increase in bleeding whatsoever in the subgroup that took aspirin versus placebo. However, the use of aspirin beyond 3 days after the procedure was not analysed, and episodes of bleeding occurred up to 19 days after the different techniques, which raises at least questionable doubts about the analysis.

As mentioned before, there are only two studies on sphincterotomies which analyse its effect, even if they are limited in their interpretation. For this reason, some authors (26) recommend withdrawing antiplatelet agents 4 to 7 days before risky procedures, and then reinitiate these agents after 7 days when prescribed as a primary or secondary prevention measure, at 10 days after a sphincterotomy, or at 14 days following polypectomy.

In testing for high risk of bleeding, it has been determined that clopidogrel should be withdrawn 5 days in advance in patients taking double antiplatelet agents (27).

What pathologies have a major risk of thrombosis before antiplatelet reversal?

-Coronary stents: early suspension of double antiplatelet agents (aspirin + clopidogrel) have a 29% (8-30%) risk of thrombosis due to stent placement (Fig. 2):

• Non drug-eluting stents: continue for 1 month.

• Drug-eluting stents (antiproliferative release): continue for 1 year (or 18 months).

-Secondary prevention (after recent AMI): there are no increased benefits for combined ASA + clopidogrel versus clopidogrel as a single agent (28).

-Primary prevention of cardiopathy in at-risk patients: double antiplatelet therapy is not specified.

-Following hip or knee arthroplasty or surgery for hip fracture: the risk is increased at 10 to 35 days, hence LMWH or fondaparinux is recommended.

In all cases, it is preferable to delay the procedure until the thrombotic risk is at the most minimal possible; in cases of double antiplatelet therapy, it is possible to either suspend clopidogrel 7 days in advance and continue with aspirin according to established guidelines, or to provide coverage with a low molecular weight heparin.

Is anticoagulation therapy a contraindication for any endoscopic technique?

-Yes, for endoscopic techniques that have a high risk of bleeding.

-In emergency cases, these techniques can be considered feasible after anticoagulation reversal (vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma or prothrombin factors) until an INR ≤ 1.4 is obtained.

What pathologies have a major risk of thrombosis before anticoagulation reversal?

ASGE (2) defines the risk of thrombosis using two degrees which have been presumed to be a general rule by other authors in manuals (29) and reviews (30), as there is no refuting evidence available in the scientific literature (Table V).

What is the clinical practice guideline for anticoagulation reversal? (Fig. 3)

In a decision-making analysis based on the implementation of ASGE5 clinical guidelines, the most cost-effective strategies were defined as follows:

-In patients with low thrombotic risk (i.e. atrial fibrillation without valvular pathology) or if the likelihood of polypectomy exceeds 60%, stop warfarin 5 days in advance.

-In terms of screening colonoscopies, in which polyps are suspected in at least 35% of cases, continue warfarin at a decreased dose.

-If the likelihood of polypectomy is minor or equal to 1%, continue with warfarin.

What role does low molecular weight heparin play in anticoagulaton reversal?

In its recommendations, ASGE (4) provides management guidelines for low molecular weight heparin utilisation as a bridge for patients at high thrombotic risk. The difficulty is that there is neither an established dosage nor an ideal timing to reinitiate heparin, although it has been suggested that this time could vary from between 2 and 6 hours after the procedure, depending upon a joint consensus by the other specialists involved. Other authors propose decreasing LMWH doses prior to interventional procedures with an early reinitiation in high-risk patients as stated below, even though it is described in a trial for diagnostic catheterizations and not for procedures with a high risk of bleeding (31).

On the other hand, there are no conclusive data in the scientific literature to recommend the use of LMWH as bridge therapy in patients treated with antiplatelet agents at high risk for thrombosis, even if it is routinely used in clinical practice (Table VI and Fig. 3).

The utilisation of low molecular weight heparin as bridge therapy is an appropriate guideline in patients at high-risk for thrombosis undergoing anticoagulant treatment, even though neither the guidelines nor the dosage have been defined as of yet.

Recommendation D

The utilisation of low molecular weight heparin as bridge therapy is a routine guideline in patients at high-risk for thrombosis undergoing antiplatelet treatment, even though it has not yet been confirmed by clinical studies.

Recommendation E

Conclusions

There is probably a lack of sufficient evidence to make decisions and recommendations with absolute certainty in each of the present situations, hence each professional healthcare team must prepare their own standards based on existing data. In this sense, we are providing you with our work proposal (see annex at the conclusion of this document).

An investigative effort must be made to define specific scenarios, especially those regarding the utilisation of double antiplatelet agents, and bridge guidelines for low molecular weight heparin, including the appropriate dosage and timing to reinitiate anticoagulation.

In patients who have an increased risk for coagulation disorders, the endoscopic technique must be specifically clear and concise, and the use of all available tools enabling appropriate bleeding control must be recommended in an explicit manner, optimizing contributory mechanical and thermal means such as clips, sutures, argon, endoloops, etc

References

1. Ezekowitz MD. Anticoagulation Interruptus: Not Without Risk. Circulation 2004; 110: 1518-9. [ Links ]

2. Eisen, GM, Baron, TH, Dominitz, JA, et al. Guideline on the management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 55: 775. [ Links ]

3. Baker RI, Coaughlin PB, Gallus AS, Harper PL, Salem HH, Word EM; the Warfarin Reversal Consensos Group. Warfarin reversal: consensus guidelines, on behalf of the Australasian Society of Trombosis and Haemostasis. Medical Journal of Australia 2004; 181(9): 492-7. [ Links ]

4. Zuckerman, MJ, Hirota, WK, Adler, DG, et al. ASGE guideline: the management of low-molecular-weight heparin and nonaspirin antiplatelet agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61(2): 189-94. [ Links ]

5. Gerson LB, Gage BF, Owens DK, Triadafilopoulos G. Effect and outcomes of the ASGE guidelines on the periendoscopic management of patients who take anticoagulants. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95(7): 1717-24. [ Links ]

6. Lobo B, Saperas E. Tratamiento de la hemorragia digestiva por ruptura de varices esofágicas. Disponible en: http://www.prous.com/digest/protocolos/view_protocolo.asp?id_protocolo=18. 2004 Prous Ed. [ Links ]

7. Cukor B, Cryer BL. The risk of rebleeding after an index GI bleed in patients on anticoagulation (abstract DDW 2008) Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 67 (5): AB243. [ Links ]

8. ASGE. Guidelines for Clinical Aplication. Position statement on laboratory testing before ambulatory elective endoscopic procedures. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 1999; 50(6): 906-9. [ Links ]

9. Parra-Blanco A, Kaminaga N, Kojima Y, et al. Hemoclipping for postpolypectomy and postbiopsy colonia bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 37-41. [ Links ]

10. Smith LE. Fiberoptic colonoscopy: complications of colonoscopy and polyupectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1976; 19: 407-12. [ Links ]

11. Sieg A, Hachmoeller-Eisenbach U, Eisenbach T. Prospective evaluation of complications in outpatient GI endoscopy: a survey among German gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 53: 620-7. [ Links ]

12. Di Giorgio P, De Luca L, Calcagno G, Rivellini G, Mandato M, De Luca B. Detachable snare versus epinephrine injection in the prevention of postpolypectomy bleeding: a randomized and controlled study. Endoscopy 2004; 36: 860-3. [ Links ]

13. Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastorintest Endosc 1991; 37: 383-93. [ Links ]

14. Hui CK, Lai KC, Yuen MF, Wong WM, Lam SK, Lai CL. Does withholding aspirin for one week reduce the risk of post-sphinterotomy bleeding? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 929-36. [ Links ]

15. Nelson DB, Freeman ML. Major haemorrhage from endoscopic sphincterotomy: risk factor analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1994; 19: 283-7. [ Links ]

16. Weinberg BM, Shindy W, Lo S. Dilatación esfinteriana endoscópica con balón (esfinteroplastia) versus esfinterotomía para los cálculos del conducto biliar común (Revisión Cochrane traducida). En: La Biblioteca Cochrane Plus, 2007 Número 4. Oxford: Update Software Ltd. Disponible en: http://www.update-software.com (Traducida de The Cochrane Library, 2007 Issue 4. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd). [ Links ]

17. Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Neumann H, Rickes S, Malfertheiner P. Diagnostic and therapeutic utility of double balloon endoscopy: experience with 225 procedures. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2007; 37(4): 216-23. [ Links ]

18. Bason MD, Manzini L, Palmer RH. Effect of nabumetone and aspirin on colonia mucosal bleeding time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001; 15: 539-42. [ Links ]

19. Nakajima H, Takami H, Yamagata K, Kariya K, Tamai Y, Nara H. Aspirin effects on colonia mucosal bleeding: implications for colonia biopsy and polypectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40(12): 1484-8. [ Links ]

20. Llau JV, de Andrés J, Gomar C, Gómez A, Hidalgo F, Sahagún J, et al. Fármacos que alteran la hemostasia y técnicas regionales anestésicas: recomendaciones de seguridad. Foro de consenso. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanima 2001; 48: 270-8. [ Links ]

21. Llau JV, de Andrés J, Gomar C, Gómez A, Hidalgo F, Torres LM. Fármacos que alteran la hemostasia y técnicas regionales anestésicas: recomendaciones de seguridad. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanima 2004; 51: 137-42. [ Links ]

22. Freeman M, Nelson D, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 909-18. [ Links ]

23. Shiffman ML, Farrel MT, Yee YS. Risk of bleeding alter endoscopic biopsy or polypectomy in patients taking aspirin or other NSAIDs. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 1994; 40: 458-62. [ Links ]

24. Hui AJ, Wong RM, China JK, Hung LC, Chung SC, Sung JJ. Risk of colonoscopic polipectomy bleeding with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents: analiysis of 1657 cases. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59: 44-8. [ Links ]

25. Yousfi M, Gostout CJ, Baron TH, et al. Postpolypectomy lower gastrointestinal bleeding: potencial role of aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99: 1785-9. [ Links ]

26. Kimchi NA, Broide E, Scapa E, Birkenfeld S. Antiplatelet therapy and the risk of bleeding induced by gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. A systematic review of the literature and recommendations. Digestion 2007; 75(1): 36-45. [ Links ]

27. Fox KA, et al. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoing surgical revascularization for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the clopidogrel in unestable angina to prevent recurrent ischemic events (CURE) trial. Circulation 2004; 110: 1202. [ Links ]

28. Diener HC, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone alter recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 331. [ Links ]

29. Kamath PS. Gastroenterologic procedures in patients with disorders of hemostasis. Up to date. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/physicians/gasthepa_toclist.asp 2007 [ Links ]

30. Morillas JD, Simón MA. Endoscopia: preparación, prevención y tratamiento de las complicaciones. En: Asociación Española de Gastroenterología. Tratamiento de las enfermedades gastroenterológicas. Ed. SCM; 2006. [ Links ]

31. Kovacs MJ, Kearon C, Rodger M, Anderson DR, Turpie AGG, Bates SM, et al. Single-arm study of bridging therapy with low-molecular-weight heparin for patients at risk of arterial embolism who require temporary interruption of warfarin. Circulation 2004; 110: 1658-63. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Fernando Alberca de las Parras.

Servicio de Aparato Digestivo.

Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca.

Ctra. Madrid-Cartagena, s/n.

30120 El Palmar, Murcia.

e-mail: f_alberca@yahoo.es

Received: 09-02-09.

Accepted: 17-02-09.

text in

text in