My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.102 n.7 Madrid Jul. 2010

Endoscopic resection as unique treatment for early colorectal cancer

Resección endoscópica de cáncer colorrectal temprano como único tratamiento

J. Ruiz-Tovar1, J. Jiménez Miramón2, A. Valle2 and M. Limones2

1Service of General Surgery and Digestive Diseases. Hospital General Universitario de Elche. Alicante, Spain.

2Service of General Surgery and Digestive Diseases. Hospital Universitario de Getafe. Madrid, Spain

ABSTRACT

Colonoscopic screening in developed countries allows detection and resection of a great number of early colorectal cancers. There is a strong controversy to decide when endoscopic treatment is enough or when surgical resection is necessary. To this contributes the diverse names to define the lesions, the wide number of classifications and the different criteria of each author. We perform an extense literature review, aiming to clarify concepts and unify criteria that can be used as a guide for the treatment of early colorectal cancer. We conclude that in early colorectal cancer arising in pedunculated polyps (0-Ip), mucosal endoscopic resection would be indicated as only treatment in Haggitt levels 1, 2 and 3, tumors smaller than 2 cm, well- or moderately differentiated, without vascular or lymphatic affection, with submucosal infiltration lower than 1 µm from the muscularis mucosae and maximal submucosal width lower than 4 µm, and undergoing en bloc resection. In sessile polyps (0-Is) or non-polypoideal elevated (0-IIa) or plain (0-IIb) lesions, recommendations will be similar, without applicability of Haggitt levels.

Key words: Early colorectal cancer. Malignant polyp. Definitive endoscopic resection.

RESUMEN

El screening mediante colonoscopia que se realiza en países occidentales ha permitido la detección y resección de un número elevado de tumores colorrectales en estadio temprano. Existe una gran controversia a la hora de decidir cuándo el tratamiento endoscópico es suficiente y cuándo debe realizarse la resección quirúrgica. A ello contribuye la gran diversidad en la nomenclatura para definir estas lesiones, la amplia variedad de clasificaciones de las mismas y los diferentes criterios que tiene cada autor. Mediante una revisión extensa de la literatura, pretendemos aclarar conceptos, enlazar los datos de las diferentes clasificaciones y unificar unos criterios que sirvan de guía para el tratamiento del cáncer colorrectal temprano. Tras ello, llegamos a la conclusión de que en el cáncer colorrectal temprano que aparece en pólipos pedunculados (0-Ip), estaría indicada la resección endoscópica como único tratamiento en los niveles 1, 2 y 3 de Haggitt, tumores menores de 2 cm de diámetro, en tumores bien o moderadamente diferenciados, sin afectación vascular ni linfática, con infiltración de la submucosa menor de 1 µm desde la muscularis mucosae y anchura máxima en la submucosa menor de 4 µm y resecados en bloque. En las lesiones polipoideas sésiles (0-Is) y no polipoideas elevadas (0-IIa) o planas (0-IIb) las recomendaciones serían las mismas descritas anteriormente, no siendo aplicables los niveles de Haggitt.

Palabras clave: Cáncer colorrectal temprano. Pólipo maligno. Resección endoscópica definitiva.

Introduction

Adenomas of the gastrointestinal tract may present malignant transformation following the histopathological sequence adenoma-carcinoma. Most colonic adenomas are considered as precursors of colorectal carcinomas. It is described in literature that between 2-10% of adenomas will develop an invasive carcinoma that can achieve up to 85% when considering villous adenomas (1-4). Screening with test for fecal occult blood and, specially, with colonoscopy, recently introduced in Western countries, has permitted the detection and resection of a great number of elevated adenomatous polyps in early stages of malignant transformation, avoiding their progression to invasive carcinoma (4-8).

Historically, most colorectal adenomas were considered polypoid structures, allowing an easy endoscopic resection. Notwithstanding, the number of flat or depressed colorectal lesions has increased in the last decades, representing up to 38% of colonic adenomas (9). Those polyps with a size bigger than 3 cm, affecting more than one third of circumference or two colonic haustras, or with flat or depressed morphology are more difficult to be resected with the conventional endoscopic polypectomy, thus with the new endoscopic approaches, such as endoscopic mucosal resection, the number of resected polyps has increased, avoiding the surgical act in many cases (10).

There is still a strong controversy around the indications of endoscopic or surgical resection, but with the advance of endoscopic techniques, the indications of endoscopic resection are growing and in fewer cases surgical treatment is necessary.

Concepts

"Malignant polyp" is considered as an adenomatous polyp macroscopically benign, whose histological study reveals an invasive carcinoma. Submucosal invasion allows vascular and lymphatic infiltration; therefore malignant polyp are able of developing lymph node metastases and, in these cases, endoscopic resection would be not curative (1,3).

The term "early colorectal cancer" was defined in Japan as the presence of neoplastic cells in mucosa and submucosa, independently of the presence or absence of lymph node metastases (11). These superficial tumors correspond with T1 stage of TNM classification, where tumor invasion is limited to mucosa and submucosa. These lesions, polypoid or sessile, should not be obstructive, being usually asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally or during the performance of a screening (12).

Macroscopic classification

Diverse classifications have been proposed to define the different types of polypoid and sessile lesions and depending on them, different indications for endoscopic resection of colorectal lesions.

The Japanese Society for study of cancer of colon and rectum divided the appearance types of early colorectal cancer into 3 categories: protruding or polypoid, flat elevated and depressed (13,14) (Table I). There is another type of lesion called lateral extension polyps, developing extensive and circumferentially in the colonic wall. These lesions are subdivided in granulated and non-granulated forms. Kudo et al. (14) considered that small flat adenomas may grow into the colonic lumen (exophitic growth) to form pedunculated polyps, or laterally to develop lateral extension lesions. Depressed lesions grow deeply (endophitic growth) and are usually associated with invasive carcinomas, even in small size lesions. In clinical practice, pedunculated polyps were considered low risk lesions that were amenable for endoscopic management, while sessile, flat, ulcerated or lateral extension ones were considered as high risk lesions and surgical resection was recommended as definitive treatment (14). Later on, this affirmation was redefined depending on the size of the lesion, limiting the absolute surgical indication for depressed lesion bigger than 1 cm, while flat, lateral extension and depressed smaller than 1 cm could be amenable for endoscopic mucosal resection (10).

In the Paris classification, polypoid type presented pedunculated/semipedunculated morphology (Type 0-Ip) or sessile (0-Is). Non-polypoideal type was divided into slightly flat (0-IIa), completely flat (0-IIb) or slightly depressed without ulcers (0-IIc). Ulcerated or excavated lesions (0-3) are very infrequent for them (15) (Table II). Following this classification, lesions type (0-IIa), (0-IIb) smaller than 2 cm and (0-IIc) smaller than 1 cm were amenable for endoscopic mucosal resection, and not recommendable in depressed or ulcerated ones (0-3) (16,17).

These classifications are still being used as useful guides to distinguish lesions amenable or not for endoscopic treatment. Notwithstanding, any of them is considered the gold standard, leading to important differences in the definition and interpretation of the lesions.

Microscopic classification

Haggitt et al. classified early colorectal cancer into pedunculated and sessile lesions. Pedunculated polyps have stems longer than their diameter, while sessile ones do not. Stem is formed by normal mucosa, muscularis mucosae and a central area of submucosal tissue. The union between stem and head is the usual point of transition from normal epithelium to an adenomatous one and is called neck. Lymphatic vessels spread in the submucosa through the stem up to the head. Haggitt stratified the polyps depending on the invasion (Table III), being the most important factor of carcinomas arising in adenomatous polyps. Invasion levels 1, 2 and 3 present low risk of lymph node metastases and are amenable for endoscopic resection (18) (Fig. 1).

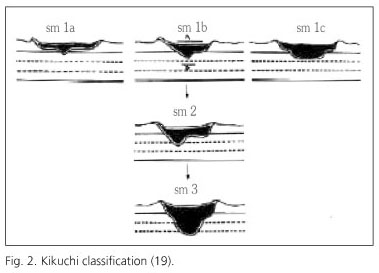

Haggitt defined the submucosal invasion in all sessile polyps as level 4 and therefore associated with bad outcome, independently of the affection or not of the resection margins (18). Despite Haggitt's classification has been widely used to evaluate the resection quality of endoscopic polypectomies, this is less useful in non-pedunculated, flat or depressed lesions. The most accepted classification for them is Kikuchi's one, quantifying the grade of vertical and horizontal submucosal invasion: submucosa is divided into superior third (Sm1), medium third (Sm2) and lower third (Sm3) (Fig. 2). Superior third is subdivided into 3 subtypes depending on horizontal spread in relation with the tumoral size (19) (Table IV). Referring to the outcome, Sm1 is equivalent to Haggitt's level 1, Sm 2 to levels 2 and 3, and Sm3 may correspond with a level 4. Sm1a or Sm1b lesions without invasion never develop metastases. Lesions with deeper or more extent affection are able to develop metastases, determining the necessity of aggregating a surgical treatment after finishing the endoscopic one (1,2,10).

Endoscopic diagnosis

With endoscopic view some features of colorectal lesions may be observed, suggesting submucosal invasion. In elevated lesions, a hart consistence, the appearance of a polyp over another one, the ulceration of the edge, the presence of satellite white points or local signs of bleeding are suggestive of invasion. In depressed lesions, the presence of bleeding points, the disruption of the mucosal capillary pattern and the local deformation of the wall are suspicious signs. When the submucosa is affected, en bloc movement of the lesion and adjacent mucosa is lost, showing a local deformation. After instillation of Indigo red 0,4% it is observed the disruption of innominated grooves in the mucosa, another suspicious sign of submucosal affection (20,21).

The development of amplification endoscopy has permitted the description of 6 patterns of organization of the glands in the colonic mucosa, called pits (Table V). According to the invasion of the submucosa, its structure is destroyed with disappearance of the gland pattern, defined as pit V. The presence of asymmetry and lack of homogeneity in the grooves determine the amorphous grade of the lesion. When the amorphous sign is present, the lesion is classified as pit Va, typical of an invasive carcinoma, while when there is no amorphism, with complete lost of the structure, it is classified as pit Vn, typical of tumors with deeper submucosal invasion (Sm2, Sm3). Actually, the pit pattern observed in amplification colonoscopy allows to differentiate a non-invasive adenoma (pits I-IV) from invasive carcinoma (pit V) and predict somehow the depth of tumor invasion before performing a treatment, improving the accuracy of endoscopic diagnosis of early colorectal cancer, mainly in depressed lesions (21,22).

Particularities of early rectal cancer

The rectum presents some features that make necessary some considerations about its diagnostic and therapeutical management. First of all, the location of a rectal tumour is important in the process of therapeutic decision. Tumors located in the last 10 cm may require neoadjuvant treatment that is not necessary in proximal tumors. On the other hand, tumors located in the last 5 cm of rectum have more chances to require sphincterian resection (23).

The treatment is conditioned by some prognostic factors: the deep invasion in the rectal wall, affection of the mesorectal fascia (circumferential resection margin) and the presence of lymph node or distant metastases. These factors are evaluated with imaging tests. The employed tests to determine local extension, that is the interesting fact in early rectal cancer, are endorectal ultrasonography (EUS) and magnetic resonance (MR). EUS is the most accurate technique to evaluate the tumor invasion into the rectal wall, being more precise in early stages (T1-T2), as occurs in early rectal cancer with invasion up to submucosa (T1) (23). EUS allows establishing the extension into mesorectal fat in T3 tumors, but does not allow to evaluate the circumferential resection margin. MR performs an adequate study of the rectal wall layers and is very exact to determine the affection of mesorectal fascia, but is less accurate to evaluate T1-T2 tumors. Both techniques have shown similar efficacy in the evaluation of regional lymph nodes, being visible only those with pathological size in the EUS and appearing hypoechoic and bigger than 1 cm in MR. Theoretically, in early rectal cancer, the probability of lymph node affection is nearly 0%, but recent studies have shown that tumors reaching the Kukuchi Sm1 level present a risk of lymph node metastases between 1-3%, increasing in Sm2 up to 8% and in Sm3 up to 23% (22). Therefore, MR and EUS are recommended after endoscopic resection, because contribute with additional information, important to predict the validity of definitive endoscopic treatment (24-27).

Indications for definitive endoscopic treatment

The role of endoscopic resection in the treatment of early colorectal cancer has been defined in the last years. Initially, only low risk malignant polyps were amenable for this treatment, and must present the following criteria: complete resection of the polyp, well or moderately differentiated histological grade, histological examination of the complete specimen (piecemeal resections were not accepted) and absence of vascular or lymphatic invasion (28,29).

Haggitt described that polyps affecting levels 1, 2 and 3 present low risk of developing lymph node metastases (< 3%) and therefore are amenable for definitive endoscopic treatment, while the affection of level 4 require surgical resection (18). Kikuchi considered that only the affection of the lower third of the submucosa (Sm3) represents a high risk for lymph node metastases, thus Sm1 and Sm2 could be candidates for endoscopic excision as unique treatment (19). Kafka and Coller recommended definitive endoscopic treatment in pedunculated polyps not reaching Haggitt's level 4, always when adverse factors, such as poorly differentiated tumors (higher lymphatic metastases rate, though submucosal affection is superficial), lymphatic or vascular invasion, or affected or very small resection margins were not present, because in those cases the risk of local recurrence is high. Sessile polyps were considered to be difficult to be completely resected endoscopically and surgical resection was recommended in all the cases (30).

The recommendations of the Japanese Society of Digestive Endoscopy include as indications for definitive endoscopic treatment all colonic adenomas and those adenocarcinomas of small size, well differentiated, limited to the mucosa or with invasion of the submucosa lower than 1 μm deep and without lymphatic or vascular invasion (10,31). Recent studies also quantify the invasion of the submucosa, indicating that deep invasion over 2 mm from muscularis mucosae or a maximum width in the submucosa over 4 mm are risk factors for lymph node metastases (32,33). Moreover, definitive endoscopic treatment is not recommended in those lesions over 2 cm size. On the other hand, they specify that flat depressed lesions are high metastatic risk ones and recommend to restrict definitive endoscopic resection for lesions smaller than 1 cm diameter (10,31).

For en bloc resections of endoscopically completely resected tumors without bad prognostic factors, 5-years survival is similar to that obtained after surgical resection. Piecemeal resection is considered acceptable only for adenomas (premalignant lesions), thus in carcinomas it is not possible to determine the grade of submucosal affection. Therefore, after piecemeal resections of carcinomas, the treatment should be completed with a surgical resection.

There are two diagnostic techniques that may offer information of great value in order to decide the optimal treatment. Amplification colonoscopy is one of them; the pit pattern may help to suggest the invasivity of the lesion. Pit patterns I-IV could be considered amenable for endoscopic resection, while pit V, amorphous or not, are very suggestive of invasivity and surgical resection would be very recommendable in these cases (19,20). The other important diagnostic technique would be EUS, showing a great correlation with histological staging referring to local invasion (T) (23).

Follow up of the patients is an essential point for the performance of a definitive endoscopic resection; it is reason enough to discard it, if follow up could not be done correctly. A close surveillance allows the detection of early recurrences. Follow up strategy is also a controversial issue. It is mandatory to perform a new colonoscopy between 1 and 3 months after definitive endoscopic resection of an early stage carcinoma. Notwithstanding, some authors consider enough a new colonoscopy 1 year after resection, when this was en bloc, considering the recurrence risk low. Other more cautious authors admit that a colonoscopy every 3-6 months during the 2 first years is advisable (10,34,35).

The aim of this study is to collect the prognostic factors established in different studies, trying to unify them and aiming to establish clear indications of definitive endoscopic treatment and recommendations of follow up that clarify a controversial theme in the clinical practice. First of all, it is very important to analyze the findings of preoperative tests: amplification endoscopy and EUS. A pit pattern V in amplification endoscopy and EUS findings suggesting tumor invasion above submucosa should be considered contraindication criteria for definitive endoscopic resection. In the histological study, we consider essential the quantification of the submucosal invasion, deeply and its lateral extension, a fact that numerous pathologists overlook, and has shown to have prognostic implications. In early colorectal cancer arising in pedunculated polyps (0-Ip) we consider indicated endoscopic resection as unique treatment in Haggitt's levels 1, 2 and 3, tumors smaller than 2 cm diameter, well and moderately differentiated, without vascular or lymphatic invasion, with submucosal invasion under 1 μm deep from muscularis mucosae and a maximal width in the submucosa under 4 μm, and undergoing en bloc resection. Deep affection over 2 mm seems to be a clear indication for surgical resection, but between 1 and 2 μm, the elective treatment is controversial, thus it must be individualized according to the circumstances of each patient.

In sessile polypoid lesions (0-Is) and non-polypoideal elevated (0-IIa) or flat (0-IIb) ones, recommendations would be similar to the previously described, without applicability of Haggitt's levels. For depressed lesions without ulceration (0-IIc), recommendations are the same, excepting that the lesion should not be bigger than 1 cm of maximum diameter; in this case, due to its more aggressive natural biology, it would be reasonable to establish 1 μm deep of submucosal invasion as an acceptable limit for definitive endoscopic resection. For depressed and ulcerated lesions, very infrequent, there is no scientific evidence to establish recommendations (Table VI). In rectal lesions we recommend to perform a MR or a EUS after endoscopic resection to evaluate the validity of the resection.

The most adequate follow up protocol would be to perform a colonoscopy 1-3 months after resection, followed by new colonoscopies every 3-6 months during the first 2 years after resection.

References

1. Seitz U, Bohnacker S, Seewald S, Thonke F, Brand B, Bräiutigam T, et al. Is endoscopic polypectomy an adequate therapy for malignant colorectal adenomas? Presentation of 114 patients and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 1789-97. [ Links ]

2. Nivatvongs S. Surgical management of malignant colorectal polyps. Surg Clin N Am 2002; 82: 959-66. [ Links ]

3. Cooper HS, Deppisch LM, Gourley WK, Kahn EI, Lev R, Manley PN, et al. Endoscopically removed malignant colorectal polyps: clinicopathologic correlations. Gastroenterology 1995; 108: 1657-65. [ Links ]

4. Cappell MS. From colonic polyps to colon cancer: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, screening and colonoscopic therapy. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 2007; 53: 351-73. [ Links ]

5. Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1977-81. [ Links ]

6. Nicholson FB, Barro JL, Atkin W, Lilford R, Patnick J, Williams CB, et al. Review article: population screening for colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 22: 1069-77. [ Links ]

7. Navarro M, Peris M, Binefa G, Nogueira JM, Miquel JM, Espinás JA, et al; Catalan Colorectal Cancer Screening Pilot Programme Group. Hallazgos colonoscópicos del estudio piloto de cribado de cáncer colorrectal realizado en Cataluña. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100: 343-8. [ Links ]

8. Diaz Tasende J, Marín Gabriel C. Cribado del cáncer colorrectal mediante test de sangre oculta en heces. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100: 315-9. [ Links ]

9. Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Adam I, Shorthouse AJ, Brown S, Sanders DS, et al. A prospective clinic-pathologic and endoscopic evaluation of flat and depressed colorectal lesions in the United Kingdom. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 2543-9. [ Links ]

10. Repici A, Pellicano R, Strangio G, Danese S, Fagoonee S, Malesci A. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early colorectal neoplasia: pathologic basis, procedures and outcome. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 1502-15. [ Links ]

11. Japanese Society for cancer of colon and rectum. Japanese classification of colorectal carcinoma: Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., LTD; 1997. [ Links ]

12. Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kudo S, Riboli E, Nakamura S, Hainant P, et al. Tumors of the colon and rectum. En: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors. WHO classification of tumors: Pathology and genetics of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon: International agency for research on cancer; 2000. p. 103-43. [ Links ]

13. Koyama Y, Kotake K. Overview of colorectal cancer in Japan: report from the Registry of the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40(Supl. 10): S2-9. [ Links ]

14. Kudo S, Kashida H, Nakajima T, Tamura S, Nakajo K. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of early colorectal cancer. World J Surg 1997; 21: 694-701. [ Links ]

15. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 58 (Supl. 6): S3-43. [ Links ]

16. Rembacken BJ, Fujii T, Cairns A, Dixon MF, Yoshida S, Chalmers DM, et al. Flat and depressed colonic neoplasms: a prospective study of 1000 colonoscopies in the UK. Lancet 2000; 355: 1211-4. [ Links ]

17. Waye JD. Endoscopic mucosal resection of colon polyps. Gastrointest Clin N Am 2001; 3: 537-48. [ Links ]

18. Haggitt RC, Glotzbch RE, Soffer EE, Wruble LD. Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinomas arising in adenomas: implications for lesions removed by endoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology 1985; 89: 328-36. [ Links ]

19. Kikuchi R, Takano M, Takagi K, Fujimoto N, Nozaki R, Fujiyoshi T, et al. Management of early invasive colorectal cancer. Risk of recurrence and clinical guidelines. Dis Colon Rectum 1995; 38: 1286-95. [ Links ]

20. Kashida H, Kudo SE. Early colorectal cancer: concept, diagnosis and management. Int J Clin Oncol 2006; 11: 1-8. [ Links ]

21. Kudo S, Rubio CA, Teixeira CR, Kashida H, Kogure E. Pit pattern in colorectal neoplasia: endoscopic magnifying view. Endoscopy 2001; 33: 367-73. [ Links ]

22. Hurlstone DP, Fujii T. Practical uses of chromoendoscopy and magnification at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2005; 15(4): 687-702. [ Links ]

23. Vila JJ, Jiménez FJ, Irisarri A, Martínez A, Amorena E, Borda F. Estadificación del cáncer de recto mediante ultrasonografía endoscópica: correlación con la estadificación histológica. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007; 99: 132-7. [ Links ]

24. Ortiz Hurtado H, Armendariz Rubio P. Cáncer de recto. En: Parrilla Paricio P, Landa García JI. Cirugía AEC. Madrid: Panamericana; 2009. p. 519-30. [ Links ]

25. Tytherleigh MG, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ. Management of early rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2008; 95: 409-23. [ Links ]

26. Lahaye MJ, Engelen SM, Nelemans PJ, Beets GL, van de Velde CJ, van Engelshoven JM, et al. Imaging for predicting the risk factors - the circumferencial resection margin and nodal disease of local recurrence in rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2005; 26: 259-68. [ Links ]

27. Pahlman L, Bohe M, Cedemark B, Dahlberg M, Lindmark G, Sjödahl R, et al. The Swedish rectal cancer registry. Br J Surg 2007; 94: 1285-92. [ Links ]

28. Morson BC, Whiteway JE, Jones EA, Macrae FA, Williams CB. Histopathology and prognosis of malignant colorectal polyps treated by endoscopic polypectomy. Gut 1984; 25: 437-44. [ Links ]

29. Hermanek P, Gall FP. Early (microinvasive) colorectal carcinoma. Pathology, diagnosis, surgical treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis 1986; 1: 79-84. [ Links ]

30. Kafka NJ, Coller JA. Endoscopic management of malignant colorectal polyps. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 1996; 5: 633-61. [ Links ]

31. Kudo S, Kashida H, Tamura T, Kogure E, Imai Y, Yamano H, et al. Colonoscopic diagnosis and management of nonpolypoid early colorectal cancer. World J Surg 2000; 24: 1081-90. [ Links ]

32. Yasuda K, Inomata M, Shiromizu A, Shiraishi N, Higashi H, Kitano S. Risk factor for occult lymph node metastases of colorectal cancer invading the submucosa and indications for endoscopic mucosal resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50: 1370-6. [ Links ]

33. Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Hashiguchi Y, Shimazaki H, Aida S, Hase K, et al. Risk factors for an adverse outcome in early invasive colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 385-94. [ Links ]

34. Noshirwani KC, van Stolk RU, Rybicki LA, Beck GJ. Adenoma size and number are predictive of adenoma recurrence: implications for surveillance colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 433-7. [ Links ]

35. Repici A, Tricerri R. Endoscopic polypectomy: techniques, complications and follow-up. Tech Coloproctol 2004; 8: 283-90. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jaime Ruiz-Tovar.

Corazón de María, 64, 7o J.

28002 Madrid.

e-mail: jruiztovar@gmail.com

Received: 29-12-09.

Accepted: 04-02-10.

text in

text in