Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.105 no.2 Madrid feb. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082013000200002

Efficacy and safety of ERCP in a low-volume hospital

Eficacia y seguridad de la CPRE en un hospital con bajo volumen

José María Riesco-López1, Manuel Vázquez-Romero2, Juana María Rizo-Pascual3, Miguel Rivero-Fernández1, Rebeca Manzano-Fernández1, Rosario González-Alonso1, Eloísa Moya-Valverde1, Antonio Díaz-Sánchez1 and Rocío Campos-Cantero1

1Department of Gastroenterology. Hospital del Sureste. Arganda del Rey, Madrid. Spain.

2Department of Gastroenterology. Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid, Spain.

3Department of Pediatrics. Hospital Infanta Sofía. San Sebastián de los Reyes, Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

Background and aims: there is little scientific evidence on the outcomes of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) performed in low-volume hospitals; however, in our country, it is growing up its implementation. The objectives of our study were to evaluate the efficacy and safety of this technique performed by two endoscopists with basic training in a center of this nature and analyze the learning curve in the first procedures.

Patients and methods: single-center retrospective study of the first 200 ERCP performed in our hospital (analyzing the evolution between the first 100 and 100 following procedures), comparing them with the quality standards proposed in the literature.

Results: from February 2009 to April 2011, we performed 200 ERCP in 169 patients, and the most common indications were: Choledocholithiasis (77 %), tumors (14.5 %) and other conditions (8.5 %). The cannulation rate rose from 85 % in the first 100 ERCP to 89 % in the next 100 procedures, clinical success from 81 % to 87 %, decreasing the post-ERCP acute pancreatitis rate from 11 % to 4 %, upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) from 3 % to 2 % and acute cholangitis from 4 % to 1 %. There was a death from a massive UGIB in a cirrhotic patient in the first group of patients and a case of biliary perforation resolved by surgery in the second one.

Conclusions: the results obtained after performing 200 procedures support the ability to practice ERCP in low-volume hospitals obtaining levels of efficacy and safety in accordance with published quality standards.

Key words: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Biliary cannulation. Sphincterotomy. Expert biliary endoscopist. Learning curve.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: existe poca evidencia científica sobre los resultados de la CPRE realizada en hospitales con bajo volumen, sin embargo su puesta en marcha en nuestro medio es creciente. Los objetivos de nuestro estudio son evaluar la eficacia y seguridad de dicha técnica realizada por dos endoscopistas biliares noveles en un centro de estas características y analizar la curva de aprendizaje en los primeros procedimientos.

Pacientes y métodos: estudio retrospectivo de las primeras 200 CPRE practicadas en nuestro hospital, analizando la progresión entre los 100 primeros procedimientos y los 100 segundos, comparándolos con los estándares de calidad propuestos en la literatura.

Resultados: desde febrero de 2009 hasta abril de 2011 se realizaron 200 procedimientos a 169 pacientes con las siguientes indicaciones: coledocolitiasis (77 %), neoplasias (14,5 %) y otras patologías (8,5 %). La tasa de canulación ascendió del 85 % en las 100 primeras CPRE al 89 % en las siguientes, el éxito clínico del 81 % al 87 %, disminuyendo la tasa de pancreatitis aguda post-CPRE del 11 al 4 %, la de hemorragia digestiva alta del 3 al 2 % y la de colangitis aguda del 4 al 1 %. Hubo un éxitus secundario a una hemorragia digestiva alta en una paciente cirrótica en el primer grupo y un caso de perforación biliar resuelto mediante cirugía en el segundo.

Conclusiones: los resultados obtenidos tras la realización de 200 procedimientos apoyan la posibilidad de practicar CPRE en hospitales con bajo volumen consiguiendo niveles de eficacia y seguridad acorde con los estándares de calidad publicados.

Palabras clave: Colangiopancreatografía retrógrada endoscópica (CPRE). Canulación biliar. Esfinterotomía. Endoscopista biliar experto. Curva de aprendizaje.

Abreviations:

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists.

ASGE: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

UGIB: Upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is one of the most important procedures in the management of biliopancreatic diseases. In 1968, the first endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of Vater was described (1) and six years later, the first endoscopic sphincterotomy (2,3). Since then, this technique has evolved from a diagnostic modality into a therapeutic procedure. This change has been possible because of the arrival of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and its noninvasive nature. ERCP is a complex test in their learning curve (4) and has potential serious complications, such as pancreatitis, bleeding, cholangitis and perforation (5-8), but in experienced hands is safe and very effective in decompression of the biliary and pancreatic ducts.

There are numerous articles related to the training that an endoscopist should receive to become competent in ERCP (9-15), though little has been published on the results obtained by biliary endoscopists in regional hospitals or low volume hospitals (16-20).

The objectives of the study are to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ERCP performed by staff with basic training in a low-volume center and to analyze the learning curve of the technique (comparing the evolution between the first 100 and 100 following procedures).

Patients and methods

This retrospective study was performed in a hospital recently created an endowment of 115 inpatient beds and a health area of 150,000 inhabitants.

Before starting, the ERCP we made a double estimation of the number of procedures that could be performed annually at our center: On the one hand, considering the formula published by British authors indicating ERCP averaging 0.9 per 1,000 inhabitants/year (21), and on the other, comparing ERCP performed by other hospitals of similar size and assigned population in our setting. In both cases, the estimated ERCP per year was more than 100 procedures, which would allow each endoscopist practicing at least 40 annual sphincterotomies (22) or 50 ERCPs/year (23-25).

To meet these needs, it was decided to assign two endoscopists, one nurse and one nursing assistant to perform the explorations. Considering the previous but limited experience of these professionals in ERCP, we conducted a training program before starting to perform it independently. Endoscopists performed a 6 month rotation (one day per week) in a referral center in order to reach the 180-200 ERCP (12,13); the nursing staff also went for training to the same hospital for four weeks up to they were familiarized with this technique.

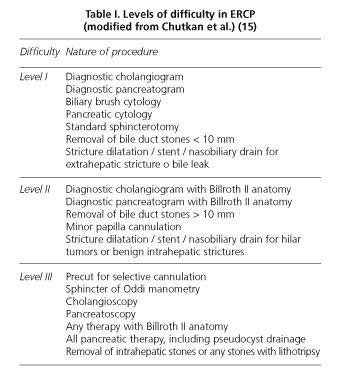

Once the training was completed, ERCP was implemented in our hospital. The first 25 explorations were performed in the X-ray room with propofol sedation in patients whose sedation risk was minimal (ASA I and II) and for institutional reasons the following 175 procedures in the operating room under general anesthesia (at the discretion of Anesthesiology Service) with portable X-ray equipment (patients ASA I-IV). According to the technical complexity we started to perform those with lower difficulty (level I according to Schutz scale, Table I) for the purpose of establishing the technique with certain guarantees of success (other patients were initially referred to the referral hospital in our area). Subsequently and gradually we performed more complicated explorations (levels II-III, Table I) with timely supervision by expert biliary endoscopists from other centers. The only complex maneuver we used from the beginning in case of difficult cannulation was the precut technique.

We design a protocol for patients who were candidates for ERCP: Both individuals hospitalized as outpatients were evaluated by a gastroenterologist before proceeding who confirmed adequate indication of the test (surrendering informed consent and explaining in detail the nature of the art); in addition, patients undergoing ERCP under general anesthesia underwent a preoperative study (electrocardiogram and chest radiograph) and were evaluated by an anesthesiologist. All patients had a recent control of hemostasis before the technique and a blood test 24 hours after ERCP to exclude complications. Those candidates scheduled ERCP on chronic oral anticoagulation therapy must replace it by subcutaneous heparin 3 days before the procedure (receiving the last dose pre-procedure: 12 hours ago) and those taking clopidogrel suspended it with 7 days notice. However we did not usually recommend stop taking aspirin. Ambulatory patients were admitted for 24 hours in the hospital, being discharged the day after the trial in the absence of complications; after discharge all individuals were reviewed in Outpatient Gastroenterology 4 weeks later to confirm adequate clinical course. Controlling appearance of post-ERCP complications was performed by specialists in Gastroenterology in normal business hours and on-call medical specialists in other slots.

The procedures were performed alternately by two endoscopists using Pentax® duoenoscopes (ED-3480TK and ED-3490TK) and rapid exchange system guide (Boston Scientific® Natick, Massachusetts and Cook Medical® Winston-Salem, NC). In those cases of increased risk of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis (after introducing inadvertently the guide-wire twice or iodinated contrast in the pancreatic duct) we placed a 5 cm - 5 French pancreatic stent (Cook Medical® Winston-Salem,NC) in order to avoid this complication, with subsequent removal within one week.

The usual working group was formed by two specialists in gastroenterology, a nurse, a nursing assistant and a radiology technician with the subsequent addition of the anesthesiology team. The modus operandi was established as follows: The nurse helped the main endoscopist (who performed the procedure) while the other endoscopist remained always in the same room to improve its learning curve, besides being responsible for monitoring sedation in the first 25 procedures.

Successful cannulation was defined as cannulation and adequate visualization of the duct/s selected before the examination. In case of cannulation of the non-desired duct, it was not considered a failure if the selected duct was achieved at the end. Clinical success was defined in case of presence of choledocolitiasis by the clearance of the stones or drainage with a stent (if lithiasis > 10 mm or presence of severe disorder of coagulation parameters) and in case of strictures if they were stented.

Information on each patient was recovered by performing a retrospective chart review and included in a database. Minor complications associated with sedation/general anesthesia could not be collected, except those serious complications that did not allow starting the procedures.

Patients over 18 years undergoing ERCP in our center were included in the study. Exclusion criteria for the study were patients with duodenal stenosis that did not allow access to the major papilla (two patients) and other who suffered oxygen desaturation during anesthetic induction and its realization was contraindicated by the anesthesiologist.

Finally, we performed a statistical analysis of the results obtained as well as the characteristics of the two groups compared in the study using the G-Stat 2.0 program. Different statistical tests were applied as comparative variables: t-Student for quantitative variables that follow normal parameters, Mann-Whitney test for non-normal groups and Chi-square and Fisher for qualitative variables.

The commissioning of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Results

From February 2009 to April 2011 we performed 200 ERCPs (74 the first year and 126 in the next 14 months) to a total of 169 patients. The median age of patients was 72 years old (range: 25-103 years old), with 63.5 % female and 36.5 % male. The most common indications were choledocholithiasis: 77 % (including biliary colic, acute cholangitis or acute pancreatitis), tumors: 14.5 % (the most common etiology was pancreatic, followed by ampullary, biliary and gastric) and other pathologies: 8.5 % (benign biliary stenosis, chronic pancreatitis or biliary leaks).

We analyzed our results separating ERCP into two groups: The first 100 vs. the following 100 procedures with similar demographic, clinical and technical characteristics without statistically significant differences (Table II).

The results obtained were as follows: Cannulation of the selected duct rate rose from 85 % in the first 100 ERCPs to 89 % in the following 100 (native papilla: 84 and 85 % respectively), clinical success from 81 to 87 %, acute post-ERCP pancreatitis decreased from 11 to 4 %, rate of acute cholangitis from 4 to 1 % and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) from 3 to 2 %, although no statistically significant differences were found (Table III). In the first group there was a death at 26 days after the procedure in a cirrhotic patient with massive bleeding hours after sphincterotomy, which could not be controlled endoscopically and required emergency surgery and admission to the ICU, with posterior development of respiratory distress related to a polytransfusional syndrome. In the second group there was a biliary perforation induced by the guide-wire in a patient with a benign biliary stenosis post-cholecysctectomy due to a clip placed in the common bile duct; perforation was resolved by surgery.

Discussion

To our knowledge, there are few publications to date on the experience of ERCP performed by biliary endoscopists with basic training (26,27) and in low-volume hospitals (17-20). However, many have been written about the training that an endoscopist should receive to be considered competent in this technique; most authors propose performing 180-200 ERCPs supervised by an expert biliary endoscopist (including different degrees of difficulty and papillary architectures) (11-13,28,29). However, more optimistic recommendations such as those made in 1996 by the Gastroenterology Core Curriculum and supported by other authors suggest that 100 ERCPs would be sufficient (9,30,31) versus 150 ERCPs required to obtain the European gastroenterology diploma (10). On the opposite extreme is the Verma et al. group who suggests the mandatory nature of performing 350 ERCPs on native papilla to ensure a mean biliary cannulation rate of 80 % (14). If we make a small advance in the requirements contemplated for biliary endoscopists with a greater number of procedures in their experience, we find that the recommended cannulation rate for experienced biliary endoscopists is estimated to be ≥ 90 % (4) and to be considered a bile duct expert over 95 % (17).

Gastroenterology specialty programs in most hospitals in Europe (10) and the U.S. (28) usually fail to reach a sufficient number of biliopancreatic procedures as those proposed previously (except Great Britain where they perform approximately 150 ERCPs), and it was found that the European average was 113 procedures (32). In our country performing ERCP is not mandatory during the period of specialization in gastroenterology and the number of ERCPs we had performed during our training period was clearly lower than the recommended to be competent in this technique, which is why we decided to go to a referral center (where they perform more than 250 procedures/year) (16) to complete our training and that of our nursing staff, since their participation after a training period also improve the results of ERCP (33,34).

The number of annual procedures that an ERCP practitioner should perform to maintain endoscopic skill and obtain an adequate technical success rate has not been unanimously established. Some authors have proposed performing an average of 40 sphincterotomies/year (22) or 50 procedures/year (23-25), though other publications recommend performing more than one sphincterotomy/week (6) or at least 200 ERCPs/year (7). Due to the demographic distribution of the population, in some countries and the healthcare resources available, sometimes this type of endoscopic procedures are performed at hospitals with low volume. In the U.S., a total of 199,625 patients undergoing ERCP during hospital admission between 1998 and 2001 were reviewed and it was shown that 70 % had been performed in hospitals with < 100 ERCPs per year, and the mean of all hospitals participating in the study was 49 ERCPs per year (range 1-1004) (35). By other side, in 2007 was determined the availability of ERCP in the U.S. from the American Hospital Association survey and it was demonstrated that it was high in metropolitan areas (35-44 %) and low in rural areas (5-25 %) (36); however, in our country, performing this procedure in non-metropolitan areas is growing, as it happens in the hospital where we work.

In our center we performed 74 ERCPs in the first year, increasing the mean in following years to 115 ERCPs per year up to the present.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the ability acquired by both endoscopists along the first 200 ERCP, and the efficacy and safety of the procedure taking into account the rate of desired duct cannulation, clinical success and complications associated to the test. Furthermore, we believe that it may be useful to assess the feasibility of creating ERCP units in hospitals with low volume taking into account the results obtained.

The decision to analyze the first 200 procedures allowed us to evaluate the evolution of technical skill acquired by both endoscopists over 26 months and objectively compare the progression of the results obtained with those recommended by most authors during ERCP training based on the same number of procedures.

Sub-analysis by groups (first 100 ERCPs versus the next 100 procedures) showed an improvement in the cannulation rate and clinical success favorable to the second 100 procedures, as well as an important reduction in the percentage of complications, although results did not reach statistical significance (probably due to the small sample size).

The cannulation rate achieved by our group is consistent with the criteria recommended by different authors and associations, who recommend reaching 80-85 % after completing their training in ERCP (14,15,24). Besides, the rate of clinical success achieved followed a parallel course to the percentage of cannulation in both groups. As regards complications, it should be noted that the rate of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis published by most groups ranges from 1.6 to 15.7 % (37,38), which in our case was seen to be elevated in the first 100 ERCPs (11 %) but decreasing to levels considered acceptable (4 %) in the next 100 procedures (39). The other complications occurring either in the first 100 ERCPs or the next 100 procedures showed similar figures to those recently recommended by the American Society of Digestive Endoscopy (ASGE) (39), emphasizing the reduction of most complications after performing first 100 ERCPs: Biliary sepsis rate (acute cholangitis) decreased from 4 % (slightly high) to 1 %, and UGIB from 3 to 2 % (similar to that published by groups with more extensive experience) (6,40). Referring to serious complications there was one case of biliary perforation and one death secondary to massive UGIB in 200 procedures analyzed. The overall complication rate in the first 100 ERCPs was above the 10 % recommended (32), though it fell to 8 % in the following procedures. Anyway, we must consider as a limitation inherent to all retrospective studies the possibility to underestimate the complications recorded.

Although this study was not designed to analyze the reasons for the decline in the rate of complications in the second 100 procedures, we believe that the acquired skill after the first 100 ERCPs allowed us to reduce the high rate of undesired pancreatic cannulation (reflected by the marked decrease in the use of pancreatic stents in the second group) and therefore the number of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis. Furthermore, the increase in the number of papiloplasty as well as precut cannulation in the second 100 ERCPs was associated with the performance of increasingly complex procedures, which although decreased the rate of acute pancreatitis and UGIB. These results agree with those recently published by other groups who demonstrate a high level of efficacy and security in the use of papiloplasty for choledocholithiasis extraction (41-43). In any case, the percentage of pre-cuts was high in both groups and we need to improve this aspect in future explorations.

If we compare the results obtained in our hospital by biliary endoscopists with basic training (from the first 100 ERCPs performed independently) with other regional hospitals or with a low volume of ERCPs, we can conclude that the results are superimposable in most cases (17,18, 20,27).

Collection of the results obtained by our group and their subsequent analysis is one of the basic criteria recommended by the ASGE to perform adequate intra- and post-procedure quality control in any ERCP unit (32).

Finally, we would stress that it is very advisable for those endoscopist who are beginning to perform ERCP autonomously (including ourselves) to refer patients requiring highly complex procedures to referral centers in this technique.

In conclusion, although this study has some limitations inherent to its retrospective nature and the results did not reach statistical significance, we believe that the practice of ERCP in our hospital reached adequate levels of efficacy and safety after making the first 200 procedures, consistent with quality standards proposed in the literature. These results suggest the possibility of practicing ERCP in low-volume hospitals provided there is adequate training of its professionals and appropriate hospital facilities.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the continued close cooperation received by the professionals of the Endoscopy Units of Hospital Ramón y Cajal and Gregorio Marañón (Madrid, Spain), well as those of Hospital La Mancha Centro from Alcázar de San Juan (Ciudad Real, Spain), Quirón (Madrid, Spain) and Río Hortega (Valladolid, Spain). Furthermore we want to show our gratitude to all colleagues who are or have been part of the Endoscopy Unit of Hospital del Sureste from Arganda del Rey (Madrid, Spain), without whose help it was not possible commissioning of ERCP in our hospital.

References

1. McCune WS, Shorb PE, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of Vater: A preliminary report. Ann Surg 1968;167:752-6. [ Links ]

2. Classen M, Demling L. Endoskopische Sphinkterotomie der Papilla Vateri und Steinextraktion aus dem Ductus choledochus. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1974;99:496-7. [ Links ]

3. Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc 1974;20:148-51. [ Links ]

4. Baron TH, Petersen BT, Mergener K, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, et al. Quality indicators for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. ASGE /ACG Taskforce for quality in endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:892-7. [ Links ]

5. Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: An attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc 1991;37:383-93. [ Links ]

6. Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:909-18. [ Links ]

7. Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: A prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;48:1-10. [ Links ]

8. Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: A prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:425-34. [ Links ]

9. Eisen GM, Dominitz JA, Faigel DO, Goldstein JL, Kalloo AN, Petersen BT, et al. Guidelines for advanced endoscopic training. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:846-8. [ Links ]

10. Bisschops R, Wilmer A, Tack J. A survey on gastroenterology training in Europe. Gut 2002;50:724-9. [ Links ]

11. Jones DB, Chapuis P. What is adequate training and competence in gastrointestinal endoscopy? Med J Aust 1999;170:274-6. [ Links ]

12. Watkins JL, Etzkorn KP, Wiley TE, DeGuzman L, Harig JM. Assessment of technical competence during ERCP training. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;44:411-5. [ Links ]

13. Jowell PS, Baillie J, Branch MS, Affronti J, Browning CL, Bute BP. Quantitative assessment of procedural competence. A prospective study of training in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:983-9. [ Links ]

14. Verma D, Gostout CJ, Petersen BT, Levy MJ, Baron TH, Adler DG. Establishing a true assessment of endoscopic competence in ERCP during training and beyond: a single-operator learning curve for deep biliary cannulation in patients with native papillary anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:394-400. [ Links ]

15. Chutkan RK, Ahmad AS, Cohen J, Cruz-Correa MR, Desilets DJ, Dominitz J A, et al. ERCP core curriculum. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:361-76. [ Links ]

16. Williams EJ, Taylor S, Fairclough P, Hamlyn A, Logan RF, Martin D, et al. Are we meeting the standards set for endoscopy? Results of a large-scale prospective survey of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatograph practice. Gut 2007;56:821-9. [ Links ]

17. Schlup MM, Williams SM, Barbezat GO. ERCP: A review of technical competency and workload in a small unit. Gastrointest Endosc 1997;46:48-52. [ Links ]

18. García-Cano Lizcano J, González Martín JA, Morillas Ariño J, Pérez Sola A. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A study in a small ERCP unit. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004;96:163-73. [ Links ]

19. Dundee PE, Chin-Lenn L, Syme DB TP. Outcomes of ERCP prospective series from a rural centre. ANZ J Surg 2007;77:1013-7. [ Links ]

20. Ciriza C, Dajil S, Jiménez C, Urquiza O, Karpman G, García L RM. Five-year analysis of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the Hospital del Bierzo. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1999;91:693-702. [ Links ]

21. Isaacs P. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography training in the United Kingdom: A critical review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011;3:30-3. [ Links ]

22. Rabenstein T, Schneider HT, Nicklas M, Ruppert T, Katalinic A, Hahn EG, et al. Impact of skill and experience of the endoscopist on the outcome of endoscopic sphincterotomy techniques. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 1999;50:628-36. [ Links ]

23. Touzin E, Decker C, Kelly L, Minty B. Gallbladder disease in north-western Ontario: the case for Canada's first rural ERCP program. Can J Rural Med 2011;16:55-60. [ Links ]

24. Cockeram A. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Practice Guideline for clinical competence in diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Can J Gastroenterol 1997;11:535-8. [ Links ]

25. Kapral C, Duller C, Wewalka F, Kerstan E, Vogel W, Schreiber F. Case volume and outcome of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: Results of a nationwide Austrian benchmarking project. Endoscopy 2008;40:625-30. [ Links ]

26. Frakes JT. An evaluation of performance after informal training in endoscopic retrograde sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol 1986;81:512-5. [ Links ]

27. García-Cano Lizcano J, González Martín JA. Training in cannulation of the bile ducts using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;23:404-5. [ Links ]

28. Kowalski T, Kanchana T, Pungpapong S. Perceptions of gastroenterology fellows regarding ERCP competency and training. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58:345-9. [ Links ]

29. García-Cano J. 200 supervised procedures: the minimum threshold number for competency in performing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc 2007;21:1254-5. [ Links ]

30. Rabenstein T, Hahn EG. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: Is the endoscopist's experience the major risk factor? JOP 2002;3:177-87. [ Links ]

31. Tavill, AS; Bissell, DM; Katz S. Training the gastroenterologist of the future: The gastroenterology core curriculum. The Gastroenterology Leadership Council. Gastroenterology 1996;110:1266-300. [ Links ]

32. Costamagna G, Familiari P, Marchese M, Tringali A. Endoscopic biliopancreatic investigations and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2008;22:865-81. [ Links ]

33. Mathews JS, Maher KA, Cattau EL. The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography injection training sessions for the gastroenterology nurse and associate. Gastroenterol Nurs 1989;12:106-8. [ Links ]

34. Ratanalert S, Soontrapornchai P, Ovartlarnporn B. Preoperative education improves quality of patient care for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterol Nurs 2003;26:21-5. [ Links ]

35. Varadarajulu S, Kilgore ML, Wilcox CM, Eloubeidi MA. Relationship among hospital ERCP volume, length of stay, and technical outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:338-47. [ Links ]

36. Poulose BK, Phillips S, Nealon W, Shelton J, Kummerow K, Penson D, et al. Choledocholithiasis management in rural America: Health disparity or health opportunity? J Surg Res 2011;170:214-9. [ Links ]

37. Cotton PB, Garrow DA, Gallagher J, Romagnuolo J. Risk factors for complications after ERCP: A multivariate analysis of 11,497 procedures over 12 years. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:80-8. [ Links ]

38. Barthet M, Lesavre N, Desjeux A, Gasmi M, Berthezene P, Berdah S, et al. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy: Results from a single tertiary referral center. Endoscopy 2002;34:991-7. [ Links ]

39. Anderson MA, Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, Ben-Menachem T, et al. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:467-73. [ Links ]

40. Rabenstein T, Schneider HT, Bulling D, Nicklas M, Katalinic A, Hahn EG, et al. Analysis of the risk factors associated with endoscopic sphincterotomy techniques: Preliminary results of a prospective study, with emphasis on the reduced risk of acute pancreatitis with low-dose anticoagulation treatment. Endoscopy 2000;32:10-9. [ Links ]

41. Martín-Arranz E, Rey-Sanz R, Martín-Arranz MD, Gea-Rodríguez F, Mora-Sanz P, Segura-Cabral JM. Safety and efficacy of large balloon sphincteroplasty in a third care hospital. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2012;104: 355-9. [ Links ]

42. Espinel J, Pinedo E. Large balloon dilation for removal of bile duct stones. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008;100:632-6. [ Links ]

43. Espinel J, Pinedo E, Olcoz JL. Large hydrostatic balloon for choledocolithiasis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007;99:33-8. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

José María Riesco-López

Department of Gastroenterology

Hospital del Sureste

Ronda del Sur, 10

28500 Arganda del Rey, Madrid. Spain

e-mail:

jmaria.riesco@salud.madrid.org

Received: 26-10-2012

Accepted: 28-01-2013

texto en

texto en