My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.105 n.4 Madrid Apr. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082013000400004

Histamine intolerance as a cause of chronic digestive complaints in pediatric patients

Intolerancia a la histamina como causa de síntomas digestivos crónicos en pacientes pediátricos

Antonio Rosell-Camps1, Sara Zibetti1, Gerardo Pérez-Esteban2, Magdalena Vila-Vidal2, Laia Ferrés-Ramis1 and Elisa García-Teresa-García1

1Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Unit

2Clinical Analyses Laboratory. Hospital Universitario Son Espases

Palma de Mallorca, Balearic Islands. Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: histamine intolerance (HI) is a poorly described disease in gastroenterology that may present with predominant digestive complaints. The goals of this study include a report of two cases diagnosed in a pediatric gastroenterology clinic.

Material and methods: observational, retrospective study of patients diagnosed with HI from September 2010 to December 2011 at the pediatric gastroenterology clinic of a tertiary hospital. They were deemed to have a diagnosis of HI in the presence of 2 or more characteristic digestive complaints, decreased diamino oxidase (DAO) levels and/or response to a low histamine diet with negative IgE-mediated food allergy tests.

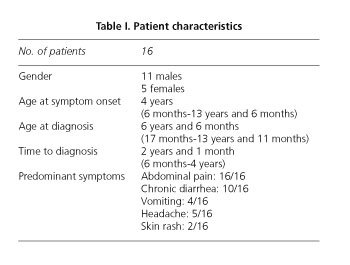

Results: sixteen patients were diagnosed. Males predominated versus females (11/5). Mean age at symptom onset was 4 years (6 months vs. 13 years and 6 months) and mean age at diagnosis was 6 years and 6 months (17 months vs. 13 years and 11 months), with an interval of 2 years and 1 month between symptom onset and diagnosis (5 months vs. 4 years). Predominant symptoms included diffuse abdominal pain (16/16), intermittent diarrhea (10/16), headache (5/16), intermittent vomiting (4/16), and skin rash (2/16). The diagnosis was established by measuring plasma diamino oxidase levels, which were below 10 kU/L (normal > 10 kU/L) in 14 cases, and symptom clearance on initiating a low histamine diet. In two patients DAO levels were above 10 kU/L but responded to diet. Treatment was based on a diet low in histamine-contaning food, and antihistamines H1 y H2 had to be added for two cases.

Conclusions: histamine intolerance is a little known disease with a potentially relevant incidence. Predominant complaints include diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache, and chronic intermittent vomiting. Its diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, plasma DAO measurement, and response to a low histamine diet. Management with the latter provides immediate improvement.

Key words: Histamine. Histamine intolerance. Enteral histaminosis. Diamine oxidase. Gastroenterology. Biogenic amines. Pediatrics.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la intolerancia a la histamina (IH) es una patología poco descrita en gastroenterología y que puede tener una sintomatología digestiva predominante. Los objetivos de este estudio son describir los casos diagnosticados en una consulta de gastroenterología pediátrica.

Material y métodos: estudio observacional y retrospectivo analizando los pacientes diagnosticados de IH desde septiembre de 2010 a diciembre de 2011 en la consulta de gastroenterología pediátrica de un hospital terciario. Se consideraron con diagnóstico de IH al presentar 2 o más síntomas digestivos característicos, determinación de diaminooxidasa disminuida y/o respuesta a la dieta baja en histamina con pruebas de alergia IgE-mediada a alimentos negativos.

Resultados: se han diagnosticado 16 pacientes. Hubo un predominio de niños (11/5) frente a las niñas. La edad media al inicio de los síntomas fue de 4 años (6 meses vs. 13 años y 6 meses) y la edad media al diagnóstico fue de 6 años y 6 meses (17 meses vs. 13 años y 11 meses). Los síntomas predominantes fueron dolor abdominal difuso (16/16), diarrea intermitente (10/16), cefalea (5/16) y vómitos intermitentes (4/16).

Conclusiones: la intolerancia a la histamina es una patología poco conocida pero con una incidencia que puede ser relevante. Los síntomas predominantes son dolor abdominal difuso, diarrea, cefalea y vómitos de aparición crónica e intermitente. El diagnóstico se realiza por sospecha clínica, determinación de diaminooxidasa plasmática y respuesta a dieta baja en histamina. Con el tratamiento de dieta baja en histamina presentan una mejoría inmediata.

Palabras clave: Histamina. Intolerancia a histamina. Histaminosis enteral. Diaminooxidasa. Gastroenterología. Aminas biógenas. Pediatría.

Introduction

Histamine intolerance (HI) is a condition that arises when there is an imbalance between excessive histamine ingestion with food or deficient histamine breakdown by detoxification systems at the intestinal and hepatic level.

Histamine (2-[4-imidazolyl]-ethylamine) is a biogenic amine with multiple effects on human organs and systems. It favors phyisiological functions in the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, respiratory, cardiovascular, cutaneous, central nervous, and immuno-hematological systems.

The presence of an excessive amount of histamine in the plasma may result from histamine release from mast cells following an allergic stimulus, excessive ingestion of histamine-containing food, or reduced histamine breakdown within the body.

Catabolism occurs along three routes. One route is represented by histamine-N-methyl-transferase (HNMT), an intracellularly acting enzyme primarily localized in the liver. It metabolizes histamine into N-methylhistamine, which is subsequently changed into N-methylimidazol acetaldehyde by monoamine oxidase (MAO) or diamine oxidase (DAO), and finally into N-methylimidazole acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). The second route is the most important one and extracellular at the intestinal level. Oxidative deamination is catalized by DAO to produce imidazole acetaldehyde, which by ALDH activity is turned into imidazole acetic acid. The third route depends upon intestinal bacteria, which acetylize histamine ingested with food (1).

The symptoms of excessive histamine in plasma may result from intoxication with spoiled food since the amino acid l-histidine in food is metabolized by bacterial decarboxylases unto histamine, thus substantially increasing histamine levels to the extent of overwhelming catabolization systems in the body, hence increasing plasma concentrations. This manifests as acute pseudoallergic illness with skin rash, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain and/or respiratory distress. Testing for IgE-mediated allergy is negative. This condition is also known as scombroid poisoning and represents a food safety concern.

Another form of histamine excess develops by intolerance. The characteristics of this condition spark more debate among authors and are not without discrepancies because in such cases manifestations are more chronic and subtle in nature, and a specific food origin is therefore difficult to prove, which entails some controversy when it comes to accepting its presence and reaching a diagnosis (2).

It results from inadequate activity in histamine-catabolizing systems (primarly DAO) because of genetic or acquired (acute gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease...) causes, or due to a chemical blocking of enzymes by drugs or alcohol.

The goal of this paper is to describe the HI cases diagnosed in our pediatric gastroenterology clinic, the diagnostic methods used, and the response of patients to treatment.

Material and methods

Patients diagnosed with HI from September 2010 to December 2011 at the pediatric gastroenterology clinic for children younger than 15 years of age were analyzed in a retrospective, observational manner.

Patients were considered to have HI according to the criteria developed by Maintz et al. (4) having two or more of the digestive complaints described for HI (vomiting secondary to multiple foods, diarrhea and/or abdominal pain) for longer than 3 months, reduced plasma diamine oxidase (DAO) levels (< 10 ku/L) and/or a positive response to a low histamine diet with negative studies for IgE-mediated food allergies.

DAO was measured by enzyme immunoanalysis in serum samples (Laboratorio Reference. Barcelona). Reference values include: For high histamine intolerance, values below 3.0 kU/L; for likely histamine intolerance, values of 3.0-10.0 kU/L; for unlikely histamine intolerance, values above 10.0 kU/L.

Histamine was measured in the plasma using radioimmunoassay techniques (Laboratorio Reference. Barcelona).

Studies to rule out food allergy were performed by means of prick tests against the food allergens most commonly seen in pediatrics: Casein, alpha-lactalbumin, beta-lactoglobulin (cow milk proteins), nuts and dried fruits, and pulses (Bial-Aristegui. Bilbao. Spain), and egg white, egg yolk, oily fish, and whitefish (ALK Abelló. Madrid. Spain). Specific IgE blood testing was also used -children younger than 5 years were screened with the Phadiatop Infant® test (Phadiatop infant, Pharmacia Diagnostics AB, Uppsala, Sweden), which detects specific IgE antibodies against milk, egg, peanut, soy, and shrimp, as well as pneumoallergens, thus covering 98 % of allergy-producing allergens in this age group. For those older than 5 years the Phadiatop Unicap® test, which only identifies pneumoallergens, and the fx5 Unicap® test (Phadiatop infant, Pharmacia Diagnostics AB, Uppsala, Suecia), which detects specific IgE antibodies against egg white, cow's milk, codfish, wheat, peanut, and soy with a sensitivity and specificity of 90 %, were used. The measurement of IgE specific for selected food components such as anisakis or gluten was performed with fluoro-enzyme immunoassay (FEIA) (InmunoCap systems. Phadia-Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Screening for celiac disease was carried out by measuring total IgA and anti-transglutaminase IgA antibodies with ELISA (Eu-tTG®IgA. Eurospital. Trieste. Italy).

Results

Sixteen patients were identified who met HI criteria. Males predominated over females (11/5). Mean age at symptom onset was 4 years (6 months vs. 13 years and 6 months), and mean age at diagnosis was 6 years and 6 months (17 months vs. 13 years and 11 months), with an interval between symptom onset and diagnosis of 2 years and 1 month (5 months vs. 4 years) (Table I).

Predominant symptoms included diffuse abdominal pain (16/16), intermittent diarrhea (10/16), headache (5/16), intermittent vomiting (4/16), and skin rash (2/16). The weight-height curve was normal.

Studies searching for IgE-mediated food allergy were performed in all cases using prick tests and/or CAP-RAST. In 6 cases prick tests were done for foods suspected to have caused symptoms according to the medical history (cow's milk proteins, egg, cereals, gluten, pork meat, veal, chicken, fish, and lentils); in 3 patients younger than 5 years the Phadiatop Infant test was used, with some other suspect allergens added according to patient history (veal, apple, pear, fig, soy, cereals, gluten, and/or latex); in 9 cases older than 5 years the fx5 test was done and other suspect foods were occasionally added and had their specific IgE measured (anisakis, gluten).

Twelve cases underwent a metabolic study (ammonium, lactic acid, amino acids in blood and urine, organic acids in urine, carnitine and/or acylcarnitines, both at baseline and during abdominal pain or vomiting episodes), which yielded normal results.

Total IgA and anti-transglutaminase IgA antibodies were tested in all cases with negative results.

Imaging studies were used for 11 cases (abdomen X-rays, follow-through, and/or abdominal ultrasounds); 6 cases were subjected to videogastroscopy with esophageal, gastric or duodenal biopsy sampling. All these tests yielded normal results (Table II).

The diagnosis was established by identifying plasma DAO levels, which were below 10 kU/L (normal > 10 kU/L) in 14 subjects, ranging from 1.3 to 8.6, and symptom clearance within 1 week after initiation of a low histamine diet (Table III). In two cases DAO levels were normal -11 kU/L and 22.1 kU/L (above 10 kU/L); however, both responded well to diet, hence they were considered HI cases.

Blood and urine histamine levels were also measured in 8 cases, but were found to be elevated in just one patient.

Manifestations also included extraintestinal symptoms such as headache (5/16) and rash (2/16). Three patients had a diagnosis of asthma, 1 of atopic dermatitis, and 1 of celiac disease. Eight cases had been previously labeled as multiple food intolerance, and two additional subjects had been referred for suspected celiac disease because of their vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

Treatment was based on a diet low in histamine-containing food; two cases that improved with diet but exhibited recurrences additionally received H1 and H2 antihistamines. Oral zinc was also added in one of them.

Discussion

Histamine intolerance, also called enteral histaminosis, is a poorly described disease in gastroenterology, with few bibliographic references. Some cases may show digestive manifestations predominantly, but diagnosis and treatment are challenging in the absence of suspicion.

In a study Hoffman et al. (5) detected an incidence of up to 4 % in children seen at the pediatric gastroenterology clinic for abdominal pain with no alert signs during a 26-month period.

Symptoms may vary a lot, be generic, and have no association with any specific food; furthermore, no accurate, affordable diagnostic test exists, which entails difficulties for diagnosis and in order to ascertain its incidence. In a systematic review by Schwelberger (3) in 2009 some papers were found with an incidence of 1 % among the general population (4), which was considered an overestimation given its diagnostic difficulties; however, the authors also deemed that a relevant number of patients would benefit from early diagnosis and therapy.

HI results from a quantitative or qualitative reduction in DAO, the primary enzyme for the catabolism of food-related histamine in the bowel, which acts as a barrier of sorts. In such cases symptoms are rather larvate and not usually associated with any specific food. Multiple complaints chronically develop as per the predominating organ or system involved. It may affect the central nervous system with headache, vertigo, nausea or vomiting; at the cardiovascular level it may cause hypotension, fast heart rate, and arrhythmia; pruritus, urticaria and rash may develop in the skin; wheezing, breathlessness and runny nose are seen in the respiratory system; there may be also dysmenorrhea, and gastrointestinal involvement may bring about diarrhea, bloating, vominting, and abdominal pain (4). In our series symptoms were primarily digestive (nonspecific abdominal pain, intermittent vomiting, and intermittent diarrhea predominantly) as these were patients referred to a pediatric gastroenterology clinic to assess their complaints; however, other non-digestive symptoms are associated, including headache, skin rash and tachycardia, that may raise suspicion of the disease.

Diagnosis is challenging given there is no specific, affordable, objective test, which entails some controversy when it comes to reconsidering this syndrome, and adds to the scarce literature available.

The presence of two or more typical symptoms, clinical improvement with a low histamine diet, and the ruling out of food allergies using prick testing or CAP-RAST (5) is recommended for the diagnosis by the authors with more experience in this disease. An oral exposure test with histamine (0.5-1 mg/kg) is also advisable, although symptoms may not always be reproduced (6,7). An oral food challenge test is recommended using previously withdrawn products. In our case we did not do this as patients had improved on the low histamine diet and their parents refused to reintroduce symptom-producing foods. DAO and HNMT measurement in the bowel mucosa is an invasive study most centers cannot afford (8). Genetic polymorphism studies of the human DAO and HNMT genes have been carried out, which found various polymorphisms, particularly for DAO; these studies, however, remain difficult to implement for clinical diagnosis (9,10). Plasma DAO and blood histamine levels are easier to determine but are not always reproducible in clinical practice.

Sixteen cases were collected during 16 months, with more than twice as many males than females (11/5) in contrast to adults, where women usually predominate.

Mean age at diagnosis was 6 years and 6 months with a rather delayed time between symptom onset and diagnosis of 2 years and 1 month. This was mostly so in the initial cases diagnosed as we ruled out other conditions, including food allergy, lactose intolerance, celiac disease, infection with Helicobacter pylori, metabolic disorders, etc., which delayed diagnosis. Once the first few cases and a good response to low histamine diet were identified the subsequent ones were more rapidly detected and the time from symptom onset to diagnosis diminished.

The predominant symptom was nonspecific abdominal pain, with no alert signs, and was seen in all 16 patients. Relapsing diarrhea events with negative cultures were seen in 10 patients. Less common were intermittent vomiting (4/16), headache (5/16), and skin rash (2/16). None of these symptoms was associated by patients with a specific food.

We found in the literature no other pediatric HI series with predominant digestive symptoms except for the report by Hoffmann et al., who in a 26-month review diagnosed with HI 16 patients where male gender and nonspecific abdominal pain predominated.

Before diagnosis with HI food allergy was excluded for all 16 cases using prick tests and CAP-RAST for predominant or clinically suspected food allergens. Metabolic studies (lactic acid, ammonium, amino acids in blood and urine, organic acids in urine, carnitine and acylcarnitines) were also undertaken for 12 patients, imaging studies (abdominal X-rays, abdominal ultrasounds, follow-through, and/or intestinal MRI) for 11 patients, and gastroscopy with biopsy for 6 patients. All these studies were normal.

For the suspected diagnosis of HI plasma DAO levels were measured -following clinical suspicion- in patients with two or more characteristic complaints. Values below 3 kU/L (considered expected intolerance) were obtained in 3 subjects, values between 3 and 10 kU/L (likely intolerance) in 11, and values above 10 kU/L (unlikely intolerance) in 2. These normal values were 11.1 kU/L and 22.1 kU/L, but the patients responded well to a low histamine diet with subsequent histamine exposure and relapse, which led to accept this diagnosis.

Blood and urine histamine levels were measured in eight HI suspects, and was seen to be elevated only in one in which blood sampling and urine collection coincided with acute abdominal pain and headache, reason why this test was not repeated for the following patients. In the review by Hoffmann (5) blood and urine histamine testing was also deemed of little use for diagnosis.

Treatment consisted of recommending a diet of foods low in histamine, to which patients usually respond in a few days, and keeping it up for 1 month in responders (subjects no longer with symptoms); foods withdrawn are then gradually reintroduced one by one. Overall, fresh foods are advisable and processed, preserved, and highly elaborated foods should be avoided.

HI is transient in many patients, who may go back to a normal diet. DAO deficiency allows histamine to enter the circulation from the bowel, hence causing complaints; subsequently, histamine metabolites inhibit HNMT, which prolongs symptoms (4). By eliminating the passage of histamine from the bowel into the circulation fewer metabolites will ensue and enzyme catabolism may be activated.

For more severe cases H1 antihistamines such as dexchlorpheniramine and H2 antihistamines such as ranitidine (8) are recommended by some authors. Supplementation with zinc, copper, vitamin C and vitamin B6, which act as cofactors for DAO, may also be administered to improve function. In our review we found two cases (one male, one female) who required medication and supplementation after huge improvement with diet because of recurrent -less often, less intense- episodes of abdominal pain.

A preparation containing porcine DAO is available as a dietary supplement indicated for histamine intolerance or its associated migraine, but we found no clinical trials to support its efficacy in children, and few do so in adults (11).

Cases associated with atopic dermatitis without food allergy have been described, which improve with histamine-low diet (12); we found one such case in our review, and diet may help control patients with multiple food allergies. HI has also been associated with migraine with digestive symptoms (13,14) and is now being related to fibromyalgia in adults. Subsequently to cases included in our series we have seen to siblings with HI whose mother was diagnosed with fibromyalgia, also had reduced DAO, and then improved with a low histamine diet.

Differential diagnosis includes food allergies, atopic dermatitis, celiac disease, carbohydrate intolerane (lactose, fructose...), migraine, cyclic vomiting syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, other functional disorders, some congenital late-onset metabolic failure in association with vomiting and abdominal pain (such as maple syrup disease), and even anorexia nervosa (15).

Recognizing this condition is not without controversy as symptoms are diverse and nonspecific, and few reports are available. While this observational, retrospective study provides a limited number of cases, our aim is that, in the face of patients with digestive illness susceptible of representing HI, the condition is more readily in mind, more cases may be diagnosed, further understanding on this disease is obtained, and unnecessary testing will be avoided.

To conclude, it should be highlighted that HI is a disorder to bear in mind for patients with chronic, nonspecific digestive issues of unclear origin. Plasma DAO measurement may help select patients for a low histamine diet, and blood and urine histamine levels are of no use for diagnosis, which will be confirmed by response to low histamine diet and subsequent challenge test with an usual diet.

References

1. Veciana Nogués MT, Vidal Carou MC. Dieta baja en histamina. En: Salas-Salvadó J, Bonada Sanjaume A, Trallero Casaña R, Saló Solà M, Burgos Peláez R, editores. Nutrición y dietética clínica. 2.a ed. Barcelona: Ediciones Elsevier España; 2008. p. 443-8. [ Links ]

2. Schwelberger HG. Histamine intolerance: A metabolic disease? Inflamm Res 2010; 59(Supl. 2):s219-s221. [ Links ]

3. Schwelerger HG. Histamine intolerance: Overestimated or underestimated? Inflamm Res 2009;58(Supl.1):s51-s52. [ Links ]

4. Maintz L, Novac N. Histamine and histamine intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1185-96. [ Links ]

5. Hoffmann K, Gruber E, Jahnel J, Deutschmann A, Hauer A. Histamine intolerance in pediatric gastroenterological practice - Diagnosis, occurrence and response to histamine-free diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48(Supl. 3):E54. [ Links ]

6. Komericki P, Klein G, Reider N, Hawranek T, Strimitzer T, Lang R, et al. Histamine intolerance: Lack of reproducibility of single symptoms by oral provocation with histamine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Wien Klein Wochenschr 2011; 123:15-20. [ Links ]

7. Wöhrl S, Hemmer W, Focke M, Rappersberger K, Jarisch R. Histamine intolerance-like symptoms in healthy volunteers after oral provocation with liquid histamine. Allergy Asthma Proc 2004;25:305-11. [ Links ]

8. Amon U, Bangha E, Küster T, Menne A, Wollrath IB, Gibbs BF. Enteral histaminosis: Clinical implications. Inflamm Res 1999;47:291-5. [ Links ]

9. Petersen J, Drasche A, Raithel M, Schwelberger HG. Analysis of genetic polymorphisms of enzymes involved in histamine metabolism. Inflamm Res 2003;52(Supl. 1):S69-S70. [ Links ]

10. Schwelberger HG, Drasche A, Petersen J, Raither M. Genetic polymorphisms of histamine degrading enzymes: From small-scale screening to high-throughput routine testing. Inflamm Res 2003;52(Supl. 1):S71-S73. [ Links ]

11. Missbichler A, Mayer I, Pongracz C, Gaboer F, Komericki P. Supplementation of enteric coated diamine oxidase improves intestinal degradation of food-borne biogenic amines in case of histamine intolerance. Clin Nutr Suppl. 6th Annual Conference of the European Nutraceutical Association (ENA). March 13th 2010, Vienna, Austria. [ Links ]

12. Chung BY, Cho SI, Ahn IS, Lee HB, Kim HO, Park CW, et al. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with a low-histamine diet. Ann Dermatol 2011;23(Supl. 1):S91-S95. [ Links ]

13. Wantke F, Götz M, Jarisch R. Histamine-free diet: Treatment of choice for histamine-induced food intolerance and supporting treatment for chronical headaches. Clin Exp Allergy 1993;23:982-5. [ Links ]

14. Gordon Millichap J, Yee MM. The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Pediatr Neurol 2003;28:9-15. [ Links ]

15. Stolze I, Peters KP, Herbst RA. Histaminintoleranz imitiert anorexia nervosa. Hautarzt 2010;61:776-8. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Antonio Rosell Camps

Pediatric Gastroenterology,

Hepatology and Nutrition Unit

Hospital Universitario Son Espases

Carretera de Valldemossa, 79

07120 Palma de Mallorca

Balearic Islands, Spain

e-mail: antonio.rosell@ssib.es

Received: 18-10-2012

Accepted: 27-02-2013

text in

text in