My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.106 n.8 Madrid Dec. 2014

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: an update on its indications, management, complications, and care

Gastrostomía endoscópica percutánea: actualización de sus indicaciones, tratamiento, complicaciones y cuidados

Alfredo J. Lucendo and Ana Belén Friginal-Ruiz

Department of Gastroenterology. Hospital General de Tomelloso. Tomelloso, Ciudad Real. Spain

ABSTRACT

Background: Numerous disorders impairing or diminishing a patient's ability to swallow may benefit from a PEG tube placement. This is considered the elective feeding technique if a functional digestive system is present.

Methods: A PubMed-based search restricted to the English literature from the last 20 years was conducted. References in the results were also reviewed to identify potential sources of information.

Results: PEG feeding has consistently demonstrated to be more effective and safe than nasogastric tube feeding, having also replaced surgical and radiological gastrostomy techniques for long term feeding. PEG is considered a minimally invasive procedure to ensure an adequate source for enteral nutrition in institutionalized and at home patients. Acute and chronic conditions associated with risk of malnutrition and dysphagia benefit from PEG placement: Beyond degenerative neuro-muscular disorders, an increasing body of evidence supports the advantages of PEG tubes in patients with head and neck cancer and in a wide range of situations in pediatric settings.

The safety of PEG placement under antithrombotic medication is discussed. While antibiotic prophylaxis reduces peristomal wound infection rates, co-trimoxazole solutions administered through a newly inserted catheter constitutes an alternative to intravenous antibiotics. Early feeding (3-6 hours) after PEG placement firmly supports on safety evidences, additionally resulting in reduced costs and hospital stays. Complications of PEG are rare and the majority prevented with appropriated nursing cares.

Conclusions: PEG feeding provides the most valuable access for nutrition in patients with a functional gastrointestinal system. Its high effectiveness, safety and reduced cost underlie increasing worldwide popularity.

Key words: PEG. Gastrostomy. Tube feeding. Enteral nutrition. Gastric feeding tubes. Intubation. Gastrointestinal. Nursing care. Complication.

Introduction

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomies (PEG), first described in 1980, have become widely used to provide enteral nutritional support to patients who are unable to ingest solid or liquid foods due to many disorders, despite having preserved absorption and motility functions of the gastrointestinal tract. In these cases, PEG tubes have arisen as an alternative to artificial parenteral nutrition and especially to nasogastric tubes, for the administration of food directly into the stomach (which is recognized as the most suitable and physiological feeding option).

PEG placement is an endoscopic technique that allows the placement of a flexible tube to create a temporary or permanent communication between the abdominal wall and the gastric cavity, ensuring the direct passing of food into the patient's digestive tract.

Even when the use of PEG tube feeding has not been universally demonstrated to decrease risks of aspiration pneumonia (1) or long term mortality, nor outcomes regarding to weight maintenance when compared with nasogastric tube feeding in several groups of patients (2), PEG feeding has been consistently demonstrated to be the feeding method with a lower probability of intervention failure, suggesting the endoscopic procedure is more effective and safe than nasogastric tube feeding, according with a Cochrane systematic review (3).

SincePonsky and Gauderer described this technique (4), PEG tubes have replaced other surgical (5) and radiological (6) gastrostomy techniques as the method of choice for long term feeding of patients who are unable to maintain adequate nutrition in the presence of a normal gastrointestinal functioning. As a result, PEG use is recognized as a minimally invasive procedure that eliminates the need for general anesthesia and requires less instrumentation, it is therefore a valuable source of nutrition by enteral feeding in nursing homes and domiciliary environments (7) when the administration period is expected to exceed 4 weeks and life expectancy of patients exceeds two months (8). It is favored by its simplicity, usefulness, safety, ease of operation and low cost (4).

This article aims to review current evidence of the indications for and advantages of PEG tube placement in variety of settings and pathological conditions. Placement techniques and procedural management of PEG tubes will also be explained and risks and potential complications discussed. Finally, specific nursing care will be provided.

A PubMed library-based search was carried out for the period between1990 and July 2014, using the following individual and combined key words: PEG tube, PEG tube feeding, complications, diet, dietary intervention, dietary treatment, enteral or parenteral nutrition, and risk factors. References cited in the articles obtained were also searched in order to identify other potential sources of information. The results were limited to human studies available in English.

Indications for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

The option to feed a patient through a PEG tube should be considered in different situations, both in hospital and at home (9). In fact, several acute and chronic conditions may be alleviated by feeding sufferers with an intact digestive tract through a PEG tube. A reduction in oral intake, generally due to neurodegenerative processes (10) represents the main reason for PEG placement in up to 90 % of cases. However, PEG tube feeding in dementia patients has been largely controversial: The extensive use of these devices in situations of oral nutrition failure contrast with of the lack of proven benefits in patients with advanced dementia, that were not demonstrated in a systematic review that included seven observational studies (10): There were no evidences of increased survival, improvement ofnutritional status or reduction of pressure ulcers prevalence rates in patients receiving enteral tube feeding. Therefore, the final decision for PEG tube placement in patients with dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases should be assessed between the physician, family and caregivers, bearing in mind the patient's advance directives (11).

Additionally, a repeated bronchial aspiration of food, or obstruction derived from oropharyngeal, neck or esophageal tumors (12) are other common indications. Table I includes the most frequent indications for PEG placement, classifying patients according to the chronicity of underlying diseases and its ability to recovery.

An increasing body of literature is documenting the potential value of prophylactic PEG tube placement at treatment initiation in patients with head and neck cancer, who are at increased risk of malnutrition and dysphagia (13). In these patients, enteral tube feeding is often required in response to dysphagia, odynophagia or other side effects of treatment that lead to dehydration and/or weight-loss during or after cancer treatment. The majority of studies published in the literature generally commence nutrition support by a PEG tube when clinically indicated in response to deterioration in swallowing or nutritional status (14-16). In contrast, some studies have reported on the commencement of enteral feeds prior to treatment (17-20), showing that prophylactic PEG placement and early tube enteral feeding was associated with a limited loss of weight, allowing an effective and safe nutrition and hydration of the patient during chemoradiation, according to retrospective chart reviews (16,18); Additionally, patients who require therapeutic PEG tube placement in response to significant weight loss during treatment suffered greater morbidity than patients who received PEG tubes prophylactically (21).

The evidence to clearly support the early placement and use of a PEG tube in patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer is weak however and the benefits versus risks have not been definitely established (22). Increasing concern that gastrostomy placement leads to prolonged tube dependency and long term dysphagia exist (23,24).

An ongoing randomized controlled trial (RCT) aimed at assessing the nutritional and clinical outcomes of patients with head and neck cancer undergoing prophylactic gastrostomy prior to treatment compared with standard practice of commencement of tube feeding (25) will shed light on this particular topic.

In the pediatric population, PEG insertion for enteral nutrition has become widely accepted, after having been demonstrated as an efficient and safe technique even in small infants, and associated with an acceptable rate of complications (26). A range of experience from clinical showing an improvement in or maintenance of adequate nutritional status in patients with a variety of underlying disorders (as well as a high level of acceptance by caregivers), has been reflected in the rising number of medical conditions for which PEG feeding is indicated in children. These include not only neurological disorders, or congenital malformations leading to oropharyngeal dysphagia, but also medical and surgical conditions impairing an adequate caloric intake, special feeding requirements (i.e. unpalatable formula in multiple food allergies or metabolic diseases) or the need for continuous enteral feeding in short bowel syndrome and malabsorption.

The use of PEG feeding in pediatric oncology has increased in last few years. In these particular situations of early PEG feeding, PEG placement is able to reverse weight loss (27) and represents a relatively safe way to prevent malnutrition in children with cancer, and subsequently might play a role in the oncological outcome (28).

Contraindications for peg placement

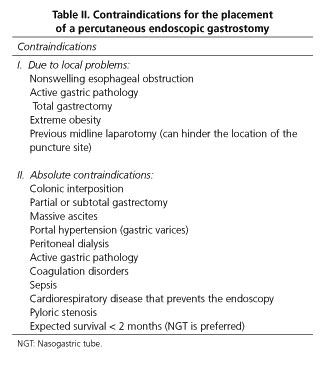

There are few absolute contraindications to PEG placement, and these mainly include technical limitations as a result of anatomical particularities such as lack of transillumination with an inability to access the anterior gastric wall, including colonic interposition and severe ascitis, uncorrectable advanced coagulopathy, portal hypertension with significant gastric varices leading to unassumable risk of bleeding; finally, pharyngeal or esophageal obstruction blocking the passage of the gastroscope to the stomach will prevent a PEG tube placement. The remaining are considered relative contraindications (Table II).

Prior abdominal surgery is currently not considered as a contraindication to PEG placement, with clinical studies showing that it can be safely placed in these patients (29), with a high success rate (30). Gastric surgery may represent a unique challenge to the endoscopist, with a 28 % of placement failures recorded in a retrospective report (29).

Preparing the patient for a peg tube placement

Informed consent

Informed consent should be obtained from patients or their legal surrogate decision makers in a consensuated way with by health professionals. Patients with advanced dementia and dysphagia usually undergo to PEG placement, so consent for a treatment in a patient without legal capacity should be guaranteed from nominated legal substitutes. The intention of informed consent is to enhance the patient's care by providing them or their caregiver with complete information on the benefits and risks of tube feeding and medications before PEG insertion (31).

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant medication

PEG is classified as an invasive interventional endoscopic procedure (32) that can result in bleeding, a complication that has been reported in approximately 2.5 % of procedures in the early literature (33,34). Patients undergoing PEG are commonly treated with aspirin and/or other antithrombotic agents, which are commonly used for treating or preventing several cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases. A major dilemma concerning patients taking these medications includes the potential risk of bleeding as a result of endoscopic intervention and the risk of thromboembolic events when such medications are withheld. Recent guidelines from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) published in 2009 for the use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for endoscopic procedures recommends that patients who are taking clopidogrel or ticlopidine should have these medications discontinued 7-10 days before PEG placement; with regard to aspirin and others non-steroideal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) endoscopic procedures may be performed while the patient is receiving this medication in the absence of a pre-existing bleeding diathesis (35). However, the ASGE guidelines are based on expert opinion and best clinical practice, since no prospective RCT trials to support them are available.

Several recent large retrospective cohort studies have been carried out to determine whether there is an association between periprocedural aspirin, clopidogrel, or ticlopidine use and bleeding in patients who underwent PEG tube placement. According to these studies, post-PEG bleeding were rare events (0 % to 2.8 %), and the use of aspirin or clopidogrel before or after PEG was not associated with procedure-related bleeding in any study (36-40). The use of dual antiplatelet therapy was not a risk factor for postprocedure bleeding, according to a retrospective multicenter study (39).

Regarding to anticoagulation, ASGE guidelines recommend that warfarin should be discontinued 3-5 days before the procedure and bridged with low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UFH) in the case of a high risk of thromboembolic complications. LMWH should be discontinued at least 8 hours before the PEG procedure; UFH infusion is recommended to be discontinued 4-6 hours before PEG and restarted 2-6 hours after the procedure is completed (35). The safety of these recommendations has been demonstrated, since the use of LMWH did not increase the risk of bleeding in the aforementioned observational studies (37).In addition, one study have suggested that patients undergoing therapeutic anticoagulation or those with increased INR values have no elevated risk of bleeding during PEG placement (40).

The safety of maintaining antiplatelet therapy in a PEG placement tube should be evaluated with further RCT, but available data supporting the individual decision to maintaining these drugs in those patients for whom the thrombotic risk is high if withdrawn, cannot be afforded.

Preventing peristomal infection

Although PEG is considered a relatively minor surgical procedure, it is associated with general complications, among which wound infection is the most common problem. The placement of a PEG tube is not considered a sterile technique and patients undergoing to it are often vulnerable to infection for a variety of reasons including old age, compromised nutritional intake, immunosuppression and underlying disease such as malignancy and diabetes (41). Bacteria colonizing the nasopharingeal and upper digestive tract may cause peristomal infection in PEG placement using the pull technique (42), a complication that is described with a frequency of up to 32 % without antibiotic prophylaxis (33,43,44).

A systematic review with meta-analysis of RCT demonstrated a significant reduction in the incidence of peristomal infection when intravenous prophylactic antibiotics were administered (pooled OR 0.31, 95 % CI, 0.22-0.44) (45). The most commonly used antibiotics to prevent peristomal infection are intravenously administered betalactamics, including co-amoxoclav, cefotaxime, cefoxitin or cefazolin, prior to PEG. A recent RCT however, comparing the administration of 20 mL of co-trimoxazole solution deposited in a newly inserted PEG catheter to cefuroxime prophylaxis given intravenously before PEG was at least as effective at preventing wound infections (46).

Peg placement technique

Patient preparation

After fasting for at least 6 hours and having a recent normal blood coagulation analysis, the medication the patient receives should be checked, especially regarding the suspension of anticoagulants or antiplatelets, if needed. A venous access should be channeled, and to prevent septic complications, broad spectrum antibiotics should be administered intravenously 30 minutes before, unless a 20 mL liquid solution of co-trimoxazole is going to be deposited through the PEG tube immediately after being inserted (47).

The abdominal skin should be shaved if needed and disinfected with a colorless disinfectant. Dentures must be removed and oral secretions vacuumed if necessary. After this, cleaning and disinfection of the oropharyngeal cavity is required, by using a swab with a suitable antiseptic solution.

Materials

The PEG device is usually marketed as a kit, including: Syringe and needle, scalpel, trocar, thread-guide, tube and snare. In addition to this material, medication for sedoanalgesia and local anesthesia should be provided, together with the tools to administer them and to aspirate oropharyngeal secretions if required.

Placement technique

To insert a PEG tube usually requires a team of 3 people (generally 2 endoscopists/gastroenterologists and a nurse). The patient is placed supine, monitored, and oxygen by nasal cannula administered. After disinfecting the abdominal wall to create a sterile field, the patients should undergo to a complete esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD), with maximal air/carbon dioxide insufflation for the extension of the wall of the stomach. The exact site of PEG insertion is determined by gastroscopic transillumination and manual palpation from outside for visualized confirmation of the appropriate placement into the lower part of the stomach.

The insertion site of the PEG tube is ideally in the median line (linea alba) to prevent hematoma and infections in the rectus muscle compartments. Next, a needle will be entering through the skin into the stomach at the location where the PEG tube is to be placed.

Three different methods have been described for PEG tube insertion: The two most widely established techniques are the pull-through method -initially described by Sacks &Vine (48), and the push method- originally described by Gauderer and Ponsky (4), due to their safety and effectiveness. In both cases, the endoscope enters through the mouth of the patient to the stomach to localize the best point to place the tube. Next, in the pull-through method, a needle is entered through the skin into the stomach at the location where the PEG tube is to be placed. A pull wire is introduced into the stomach and detected with an endoscopic snare or forceps. Then, the endoscope is slowly withdrawn until the wire appears at the mouth of the patient, and fixed to the PEG device. The PEG tube is introduced through the mouth into the stomach; indicated by meeting a resistance in the inner part of the tube to reach its final position, appearing from inside of the stomach.

The push method requires the puncture of the stomach with a double gastropexy scalpel performed under general anesthesia, with a distance of 2 cm between the two points. Between these two fixations, a puncture cannula is advanced into the stomach and a feeding tube is inserted through it. Thereafter, the puncture cannula is removed. The intragastral fixation balloon is filled with a syringe with saline solution to prevent a dislocation. Gastropexy sutures will be removed after some days. This technique avoids the passage of the PEG tube along the patient's upper aero-digestive tract.

The third method for PEG insertion, described by Russell (49), consists of inserting the tube through the abdominal wall after using stents and should be considered when the passage of the tube through the mouth needs to be prevented.

Several retrospective series have compared the pull-through and push methods (50-53). In general, pull-through PEG carried out by endoscopic teams were technically easier; push PEG showed a overall significantly higher rate of complications, dislocations and occlusions, but not in patients with advanced head, neck and esophageal cancer, among whom push-PEGs are preferred. As such, the final decision as to which PEG tube should be used depends on individual conditions.

A repeat endoscopical monitoring to determine optimal placement and to ensure the absence of immediate complication is always recommended; in particular, to set the external bumper under direct vision, which is paramount to prevent a buried bumper syndrome (BBS) (54).

Patient care after PEG placement

It is recommended to take bed rest for at least 6 hours after placement and to monitoring closely all vital signs as well as any occurrence of abdominal pain, fever or gastrointestinal bleeding. It is advisable to keep a peripheral venous line inserted for at least 6 hours in case complications arise. Additionally, some analgesia may be required during the first two days, especially in the case of children (55).

The moment for initiating peg feeding

Feeding trough PEG tubes have traditionally been delayed until the following day after its placement due to the fear of immediate post procedural complications, including peritoneal leakage and bleeding.Several observational studies however (56,57), RCTs (58,59) and a systematic review with a meta-analysis (60) have evaluated the differences between early feeding (i.e. starting liquid and/or nutritional formula administrations in the first 3 to 6 hours after placement) compared with delayed feeding (i.e. from 12 hours after insertion up to the following day). In the case of early feeding, no significant differences in local infections, diarrhea, bleeding, GERD, fever, vomiting, stomatitis, leakage, and death were noted among patients. Furthermore, in addition to early feeding being safe and well tolerated, it also results in a reduction of costs and a decrease in hospitalization.

Parallel results have been also reproduced among pediatric patients (61). Therefore, early feeding through PEG tube is recommended as it provides the patient and healthcare systems with the safest and most cost-effective results.

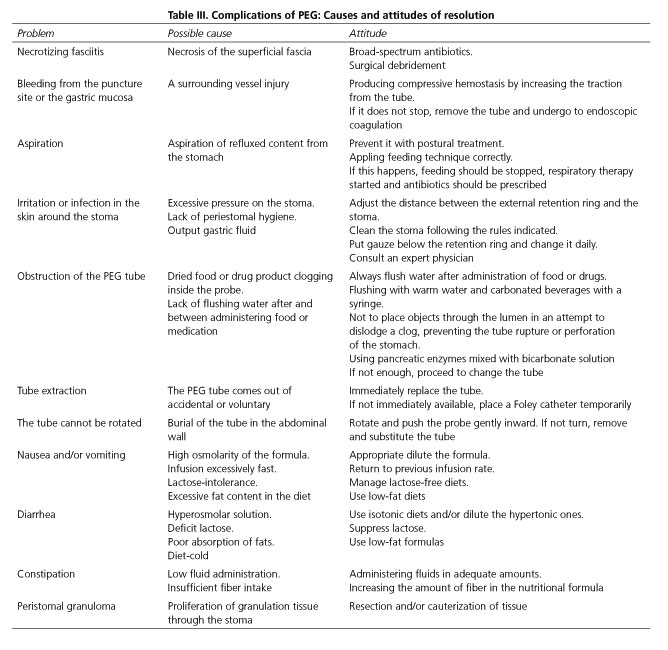

Complications of peg

The insertion of a PEG tube is a safe method with few complications (that are clinically minor and easily resolved). The incidence rates for serious and minor complication have been estimated to be 3 % and 6 %, respectively. Immediate mortality after the procedure appears is less than 1% (62,63). Table III describes the most common complications, their causes and measures for resolution.

Identifying risk factors for complications

There are several retrospective reports rising awareness of the risk factors for PEG-related complications, with the aim of decreasing patient discomfort and healthcare costs (64-70). Among the non-modifiable risk factors, advanced age is recognized as increasing the risk of death after PEG insertion in 1 %/year(65); specifically an age of more than 75 years has been identified as a predictive factor for early death 1 month after PEG placement (OR = 2.49; 95 % CI = 1.47-4.21) (64). Malnutrition, expressed both as a decreased body mass index and low serum albumin levels, is repeatedly associated with a high mortality and high complication rate after PEG, as well as the presence of comorbidities. In fact, the subrogates high C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and abnormal leukocyte counts were related with an increased early mortally rate (66). The coexistence of congestive heart failure, renal failure, urinary tract infection, previous aspiration, chronic pulmonary disease, coagulopathy, circulation disorders, metastatic cancer, and liver disease were all of them strongly associated with an increased mortality. The sum of several risk factors in the same patient also greatly increases the likelihood of early death after insertion of a PEG tube; thus, the presence of 3 risk factors multiplied by 6 increases the probability of death at 1 month compared to patients who had no risk factors (64).

The risk of complications, including death, should always be assessed individually in each patient undergoing PEG tubes insertions; however, we must always bear in mind that enteral feeding is superior to parenteral feeding in the nutritionally depleted patient, and PEG feeding remains the safer, easier and less expensive method for tube feeding for a wide range of severely compromised patients. Indeed, the indication for PEG is strongly associated itself with mortality (65).

PEG tube placement by an inexperienced endoscopist has been identified as a modifiable risk factors related to early complications. Furthermore, the insertion of the internal bumper of a PEG tube in the upper body of the stomach also was a significant risk for early and late complications (66).

Interestingly, some recent multicenter retrospective research has shown that proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) users (defined as patients who were taking standards doses of PPIs at least 48 hours before PEG placement) were associated with adverse PEG-related complications (including mortality, bowel perforation, post-procedural gastrointestinal bleeding, peritonitis, fever, pneumonia, peristomal leaks, or infection) when compared with patients non PPIs users (71).

Head and neck cancer patients have a higher risk for procedure related mortality following gastrostomy than mixed patient populations, according to a systematic review specifically conducted to defined the optimum technique for gastrostomy placement in this particular patients (72). This research also showed that major complication rates following radiologically inserted gastrostomy were greater than those following PEG in patients with head and neck cancer.

Removal and replacement of the PEG

After 2-3 weeks of being placed, a fistulous gastrocutaneous tract is formed, allowing the easy removal of the gastrostomy tube. A PEG tube can be removed when the reason for its placement has been resolved: in these cases, the gastrocutaneous fistula will spontaneously close after 24-72 hours. Most of PEG tubes, however, are placed due to chronic or progressive disorders, so the tube should be periodically replaced, after a half-life of 3-6 months that can be extended up to 12-18 months if properly cared for.

A PEG tube can be removed by strong and sustained traction until the internal bumper goes through the stoma (percutaneous method); alternatively, the tube can be removed with aid of endoscopy, by linking the gastric bumper of the tube with a polypectomy snare (endoscopic method). A recent observational retrospective study has analyzed the advantages of both methods of PEG removal in terms of associated complications (73): The immediate complication rate was lower with the percutaneous removal method, with no significant differences in the late complications rate between the two methods. Peristomal bleeding was not associated with antiplatelet or warfarin use, age, gender, or short interval tube replacement. In contrast, old age was a significant risk factor of mechanical complication during PEG tube replacement (OR, 3.83; 95 % CI, 1.04-14.07, p = 0.043). The authors concluded that the percutaneous method may be safer and more feasible for replacing PEG tubes in older patients in order to prevent such mechanical complications as esophageal injury. These results should be further validated with prospective RCTs.

Subsequently, a replacement gastrostomy tube is inserted through the stoma into the stomach and the balloon in its tip is filled in with saline or methylene blue (between 6 and 20 mL, depending on the manufacturer and model); the tube is fixed externally with a retention ring.

The substitution of a PEG tube is an easy technique that should be learned by primary care professionals, to reduce economic costs, patient anxiety and of their caregivers (thus providing greater comfort) (74).

In case of tube removal -accidental or intentional-, its early re-implantation is a priority in order to avoid the closure of the gastrocutaneous fistula. Where immediate accessing to an Endoscopy Unit in not possible, or the necessary equipment is not available, a Foley-type catheter with an inflated balloon in the gastric lumen can be used to preserve the tract and to ensure the nutrition and hydration of the patient.

"Buried bumper syndrome": A potentially fatal complication

Buried bumper syndrome (BBS) is an uncommon and late complication of PEG (with most cases occurring from months to years after placement) that occurs when the internal bumper of the PEG tube erodes into the gastric wall and lodges itself between the gastric wall and the skin. If not adverted, it can lead to a variety of additional severe complications, including wound infection, peritonitis, and necrotizing fasciitis (75,76). The most common management of BBS consists of removing the PEG tube smoothly, by external traction and replacing it with a new PEG tube using the pull-through method or balloon replacement tube after dilation of the old tract (77). An alternative and successful endoscopic method has also been described, that consists of introducing a conventional papillotome over a wire into the stomach, drawing it back as far as possible, and making incisions in all four directions to advance the tube with the internal bumper into the stomach (78,79).

Concern over BBS in the endoscopic literature, however, has led increasingly to recommendations for loose placement of the external bolster. It should be noted that leaving the external bolster too loose at the time of PEG placement increases the risk of leakage and peritonitis (54), due to internal leakage of gastrointestinal secretions and enteral formula into the peritoneal cavity. In almost all cases, the technique of PEG placement itself brings the gastric and anterior abdominal walls into apposition, forming a seal, which is also ensured by the contraction of the thick gastric musculature around the PEG tube (80).

Care of the patient with a peg tube

Proper long lasting care is essential in avoiding PEG-related complications, in guaranteeing the correct nutritional status of the patient and in ensuring an extended half-life for the tube. Nursing care should include three distinct aspects.

PEG tube care

As highlighted above, the PEG tube may be used immediately after insertion, but it is recommended to wait approximately 3-6 hours before administering solutions to the patient however, in order to observe any early complication, in particular bleeding. Small amounts of water and nutritional formula should be administered and progressively increased up to the fully prescribed volume within a 2-3 days period (81).

The tube and its components (plugs and retention rings), should be cleaned daily with a swab, mild soap and warm water, rinsing and drying well after being used. The caps will remain closed when the tube is not in use. Checking periodically for proper inflation of the balloon in replacement tubes is also necessary.

To avoid injury from decubitus over the abdominal and gastric walls, the tube should be daily rotated, clockwise and counterclockwise. Daily monitoring to ensure that the external support does not press onto the patient's skin is required, as is changing the mounting location of the tube. A dressing between the skin and external fixation should not be placed, as this would cause undue pressure. Only in cases where drainage is present, a dressing may be used, but should be changed frequently when soiled.

Stoma care

During the first two weeks after PEG insertion, the peristomal area should be clean daily with soft soap and water, from the inside out, drying well, and disinfecting with antiseptic and sterile gauze around the stoma -checking that there is no irritation, inflammation or gastric secretions. A small liquid drainage from granulation tissue of the stoma may be normal during these first weeks however.

It is recommended that the patient uses loose clothing so as not to press the stoma. If the stoma is not red, the patient can shower within a week.

Care during feeding

An adapted nutrition formula should be used, rather than grinding regular foods, as this will contain high amounts of water or oil reach a proper consistency for it to be administered through the tube; it will not have an adequate and balanced supply of nutrients and will be generally deficient in protein and excessive in fat. The formula may be administered by gravity, in a syringe or with a low-pressure feeding pump, either continuously or intermittently. The patient must be positioned at a 30-45o angle to facilitate gastric emptying and prevent reflux. This position must be maintained for an hour after completion of the feeding. The feeding formula should be administered at room temperature, starting at low volumes, increasing progressively as tolerance rises.

After food or drugs administration, it is necessary to instill 50 mL of water to flush any residue from the tube. In absence of a fluid restriction, it is recommended to use a large flushing volume, when possible. In case of continuous nutrition, it should be done every 4-6 hours. A syringe of 30 mL or greater is recommended, in order to avoid too much pressure and consequently the rupture of any component of the PEG tube (82).

In case of PEG tube obstruction, the use of pancreatitis enzymes mixed with a bicarbonate solution has been shown to be an effective method for unclogging the tube; after that, the PEG should be flushed with warm water and carbonated beverages. Finally, an effective method for unclogging the tube in some studies consists of using pancreatic enzymes mixed with bicarbonate solution, prior to flushing with warm water and carbonated beverages (63).

The patency of the tube can be checked by slowly aspirating gastric contents. It has been recommended that if greater than 100 mL, the content should be reintroduced and waiting for an hour before increasing the volume.

Administering medication through the PEG tube

The evidence regarding the effectiveness of nursing interventions in minimizing the complications associated with administering medication via enteral tubes is limited, with a lack of high-quality research on many important issues (83). However, a systematic review allows us to provide some recommendations to be considered when administering medications to a patient carrying a PEG tube:

All kinds of medications will be given diluted in water and unmixed, providing 5-30 mL of water after each and should never be mixed with formula. Enteric coated and sustained released pills should never be crashed; chewable, cytotoxic preparations, or sublingual tablets are not recommended. Bulk-forming tablets, such as Metamucil are prohibited. Hypertonic and concentrated drugs should be diluted in water before administration. Warfarin, phenitoin, morphine sulphate and aluminum-containing antiacids should not be given in conjunction with feeding because of delayed drug response (84).

If available, liquid form medications are preferable since they may prevent occlusion of silicone PEG tube and nasoenteral tubes compared to solid forms. Diarrhea has been attributed to the sorbitol content in many liquid medications, rather than the drug itself, so are not advised. Effervescent drug preparations should also be avoided in order to prevent tube occlusion (85).

Conclusions

Feeding through a PEG tube is the desirable method to feed patients with dysphagia or in those patients who are unable to feed orally but have a functioning digestive system. The technique has become more widespread do to its simplicity, safety and low cost. For proper conduct, specific training for professionals responsible for these procedures is required, and in turn, from them to provide training and information to other professionals and caregivers involved in patient care. Administering proper care tailored and customized to each case, adopting preventive strategies, identifying and treating early complications will maximize safety and effectiveness outcomes for patients.

References

1. Onur OE, Onur E, Guneysel O, Akoglu H, Denizbasi A, Demir H. Endoscopic gastrostomy, nasojejunal and oral feeding comparison in aspiration pneumonia patients. J Res Med Sci 2013;18:1097-102. [ Links ]

2. Wang J, Liu M, Liu C, Ye Y, Huang G. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding for patients with head and neck cancer: A systematic review. J Radiat Res 2014;55:559-67. [ Links ]

3. Gomes CA, Jr., Lustosa SA, Matos D, Andriolo RB, Waisberg DR, Waisberg J. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding for adults with swallowing disturbances. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;3:CD008096. [ Links ]

4. Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ Jr. Gastrostomy without laparotomy: A percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg 1980;15:872-5. [ Links ]

5. Shaver WA, Winer SF, Nyder EJ. Gastrostomy: A simple and effective technique. South Med J 2014;81:719-23. [ Links ]

6. Laskaratos FM, Walker M, Gowribalan J, Gkotsi D, Wojciechowska V, Arora A, et al. Predictive factors for early mortality after percutaneous endoscopic and radiologically-inserted gastrostomy. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:3558-65. [ Links ]

7. Dwolatzky T, Berezovski S, Friedmann R, Paz J, Clarfield AM, Stessman J, et al. A prospective comparison of the use of nasogastric and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes for long-term enteral feeding in older people. Clin Nutr 2001;20:535-40. [ Links ]

8. Sartori S, Trevisani L, Tassinari D, Gilli G, Nielsen I, Maestri A, et al. Cost analysis of long-term feeding by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in cancer patients in an Italian health district. Support Care Cancer 1996;4:21-6. [ Links ]

9. Ditchburn L. The principles of PEG feeding in the community. Nurs Times 2006;102:43-5. [ Links ]

10. Sampson EL, Candy B, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding for older people with advanced dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD007209. [ Links ]

11. Raykher A, Russo L, Schattner M, Schwartz L, Scott B, Shike M. Enteral nutrition support of head and neck cancer patients. Nutr Clin Pract 2007;22:68-73. [ Links ]

12. Potack JZ, Chokhavatia S. Complications of and controversies associated with percutaneos endoscopic gastrostomy: Report of a case and literature review. Medscape J Med 2008;10:142. [ Links ]

13. Lucendo Villarín AJ, Polo Araujo L, Noci Belda J. Cuidados de enfermería en el paciente con cáncer de cabeza y cuello tratado con radioterapia. Enferm Clin 2005;15:175-9. [ Links ]

14. Scolapio JS, Spangler PR, Romano MM, McLaughlin MP, Salassa JR. Prophylactic placement of gastrostomy feeding tubes before radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer: Is it worthwhile? J Clin Gastroenterol 2001;33:215-7. [ Links ]

15. Nugent B, Parker MJ, McIntyre IA. Nasogastric tube feeding and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding in patients with head and neck cancer. J Hum Nutr Diet 2010;13:277-84. [ Links ]

16. Raykher A, Correa L, Russo L, Brown P, Lee N, Pfister D, et al. The role of pretreatment percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in facilitating therapy of head and neck cancer and optimizing the body mass index of the obese patient. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2009;33:401-10. [ Links ]

17. Nguyen NP, North D, Smith HJ, Dutta S, Alfieri A, Karlsson U, et al. Safety and effectiveness of prophylactic gastrostomy tubes for head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemoradiation. Surg Oncol 2006;15:199-203. [ Links ]

18. Wiggenraad RG, Flierman L, Goossens A, Brand R, Verschuur HP, Croll GA, et al. Prophylactic gastrostomy placement and early tube feeding may limit loss of weight during chemoradiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer, a preliminary study. Clin Otolaryngol 2007;32:384-90. [ Links ]

19. Marcy PY, Magne N, Bensadoun RJ, Bleuse A, Falewee MN, Viot M, et al. Systematic percutaneous fluoroscopic gastrostomy for concomitant radiochemotherapy of advanced head and neck cancer: Optimization of therapy. Support Care Cancer 2000;13:410-3. [ Links ]

20. Beer KT, Krause KB, Zuercher T, Stanga Z. Early percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy insertion maintains nutritional state in patients with aerodigestive tract cancer. Nutr Cancer 2005;52:29-34. [ Links ]

21. Cady J. Nutritional support during radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: The role of prophylactic feeding tube placement. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2007;11:875-80. [ Links ]

22. Locker JL, Bonner JA, Carroll WR, Caudell JJ, Keith JN, Kilgore ML, et al. Prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in treatment of head and neck cancer: A comprehensive review and call for evidence-based medicine. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2011;35:365-74. [ Links ]

23. Langmore S, Krisciunas GP, Miloro KV, Evans SR, Cheng DM. Does PEG use cause dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients? Dysphagia 2012;13:251-9. [ Links ]

24. Mekhail TM, Adelstein DJ, Rybicki LA, Larto MA, Saxton JP, Lavertu P. Enteral nutrition during the treatment of head and neck carcinoma: Is a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube preferable to a nasogastric tube? Cancer 2001;91:1785-90. [ Links ]

25. Brown T, Banks M, Hughes B, Kenny L, Lin C, Bauer J. Protocol for a randomized controlled trial of early prophylactic feeding via gastrostomy versus standard care in high risk patients with head and neck cancer. BMC Nurs 2014;13:17. [ Links ]

26. Fröhlich T, Richter M, Carbon R, Barth B, Köhler H. Review article: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in infants and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:788-801. [ Links ]

27. Parbhoo DM, Tiedemann K, Catto-Smith AG. Clinical outcome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children with malignancies. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;56:1146-8. [ Links ]

28. Schmitt F, Caldari D, Corradini N, Gicquel P, Lutz P, Leclair MD, et al. Tolerance and efficacy of preventive gastrostomy feeding in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;59:874-80. [ Links ]

29. Foutch PG, Talbert GA, Waring JP, Sanowski RA. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients with prior abdominal surgery: virtues of the safe tract.Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:147-50. [ Links ]

30. Eleftheriadis E, Kotzampassi K. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy after abdominal surgery. Surg Endosc 2001;15:213-6. [ Links ]

31. Rahnemai-Azar AA, Rahnemaiazar AA, Naghshizadian R, Kurtz A, Farkas DT. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: Indications, technique, complications and management. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:7739-51. [ Links ]

32. Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, Faigel DO, Goldstein JL, Johnason JF, et al. Guideline on the management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:775-9. [ Links ]

33. Luman W, Kwek KR, Loi KL, Chiam MA, Cheung WK, Ng HS. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy -indications and outcome of our experience at the Singapore General Hospital. Singapore Med J 2001;42:460-5. [ Links ]

34. Schapiro GD, Edmundowicz SA. Complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 1996;6:409-22. [ Links ]

35. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, et al. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:1061-70. [ Links ]

36. Richter JA, Patrie JT, Richter RP, Henry ZH, Pop GH, Regan KA, et al. Bleeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is linked to serotonin reuptake inhibitors, not aspirin or clopidogrel. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:22-34. [ Links ]

37. Singh D, Laya AS, Vaidya OU, Ahmed SA, Bonham AJ, Clarkston WK. Risk of bleeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Dig Dis Sci 2012; 57:973-80. [ Links ]

38. Ruthmann O, Seitz A, Richter S, Marjanovic G, Olschewski M, Hopt UT, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Complications with and without anticoagulation. Chirurg 2010;81:247-54. [ Links ]

39. Lee C, Im JP, Kim JW, Kim SE, Ryu DY, Cha JM, et al. Risk factors for complications and mortality of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: A multicenter, retrospective study. Surg Endosc 2013;27:3806-15. [ Links ]

40. Richter-Schrag HJ, Richter S, Ruthmann O, Olschewski M, Hopt UT, Fischer A. Risk factors and complications following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: A case series of 1041 patients. Can J Gastroenterol 2011;25:201-6. [ Links ]

41. Lee L, Kim J, Kim Y, Yang J, Son H, Peck K, et al. Increased risk of peristomal wound infection after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients with diabetes mellitus. Dig Liver Dis 2002;34:857-61. [ Links ]

42. Hull M, Beane A, Bowen J, Settle C. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy sites. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1883-8. [ Links ]

43. Mahadeva S, Sam IC, Khoo BL, Khoo PS, Goh KL. Antibiotic prophylaxis tailored to local organisms reduces percutaneous gastrostomy site infection. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:760-5. [ Links ]

44. Grant JP. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Initial placement by single endoscopic technique and long-term follow-up. Ann Surg 1993;217:168-74. [ Links ]

45. Lipp A, Lusardi G. Systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;11:CD005571. [ Links ]

46. Blomberg J, Lagergren P, Martin L, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Novel approach to antibiotic prophylaxis in percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG): Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c3115. [ Links ]

47. Lagergren J, Mattsson F, Lagergren P. Clinical implementation of a new antibiotic prophylaxis regimen for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e003067. [ Links ]

48. Sacks BA, Vine HS, Palestrant AM, Ellison HP, Shropshire D, Lowe R. A nonoperative technique for establishment of a gastrostomy in the dog. Invest Radiol 1983;18: 485-7. [ Links ]

49. Russell TR, Brotman M, Norris F. Percutaneous gastrostomy. A new simplified and cost-effective technique. Am J Surg 1984;148: 132-7. [ Links ]

50. Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Ryan JA Jr. When push comes to shove: A comparison between two methods of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol 1986;81:642-6. [ Links ]

51. Tucker AT, Gourin CG, Ghegan MD, Porubsky ES, Martindale RG, Terris DJ. 'Push' versus 'pull' percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in patients with advanced head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 2003;113:1898-902. [ Links ]

52. Köhler G, Kalcher V, Koch OO, Luketina RR, Emmanuel K, Spaun G. Comparison of 231 patients receiving either "pull-through" or "push" percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Surg Endosc 2014; DOI 10.1007/s00464-014-3673-9. [ Links ]

53. Pang AS, Wong SK. The mathematics behind the twin-stoma gastrostomy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2012;104:221-2. [ Links ]

54. McClave SA, Jafri NS. Spectrum of morbidity related to bolster placement at time of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: Buried bumper syndrome to leakage and peritonitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2007;17:731-46. [ Links ]

55. Heuschkel RB, Gottrand F, Devarajan K, Poole H, Callen J, Dias JA, et al. ESPGHAN Position Statement on the Management of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) in Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014. DOI: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000501. [ Links ]

56. Vyawahare MA, Shirodkar M, Gharat A, Patil P, Mehta S, Mohandas KM. A comparative observational study of early versus delayed feeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Indian J Gastroenterol 2013;32:366-8. [ Links ]

57. Cobell WJ, Hinds AM, Nayani R, Akbar S, Lim RG, Theivanayagam S, et al. Feeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: Experience of early versus delayed feeding. South Med J 2014;107:308-11. [ Links ]

58. McCarter TL, Condon SC, Aguilar RC, Gibson DJ, Chen YK. Randomized prospective trial of early versus delayed feeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:419-21. [ Links ]

59. Choudhry U, Barde CJ, Markert R, Gopalswamy N. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a randomized prospective comparison of early and delayed feeding. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;44:164-7. [ Links ]

60. Bechtold ML, Matteson ML, Choudhary A, Puli SR, Jiang PP, Roy PK. Early versus delayed feeding after placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2919-24. [ Links ]

61. Islek A, Sayar E, Yilmaz A, Artan R. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children: Is early feeding safe? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;57:659-62. [ Links ]

62. Vanis N, Saray A, Gornjakovic S, Mesihovic R. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG): Retrospective analysis of a 7-year clinical experience. Acta Inform Med 2012;20:235-7. [ Links ]

63. Schrag SP, Sharma R, Jaik NP, Seamon MJ, Lukaszczyk JJ, Martin ND, et al. Complications related to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. A comprehensive clinical review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2007;16:407-18. [ Links ]

64. Light VL, Slezak FA, Porter JA, Gerson LW, McCord G. Predictive factors for early mortality after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;42:330-5. [ Links ]

65. Arora G, Rockey D, Gupta S. High In-hospital mortality after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: Results of a nationwide population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1437-44. [ Links ]

66. Lee SP, Lee KN, Lee OY, Lee HL, Jun DW, Yoon BC, et al. Risk factors for complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59:117-25. [ Links ]

67. Lang A, Bardan E, Chowers Y, Sakhnini E, Fidder HH, Bar-Meir S, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Endoscopy 2004;36:522-6. [ Links ]

68. Figueiredo FA, da Costa MC, Pelosi AD, Martins RN, Machado L, Francioni E. Predicting outcomes and complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Endoscopy 2007;39:333-8. [ Links ]

69. Smith BM, Perring P, Engoren M, Sferra JJ. Hospital and long-term outcome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Surg Endosc 2008;22:74-80. [ Links ]

70. Higaki F, Yokota O, Ohishi M. Factors predictive of survival after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in the elderly: is dementia really a risk factor? Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1011-6. [ Links ]

71. Im JP, Cha JM, Kim JW, Kim SE, Ryu DY, Kim EY, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use before percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is associated with adverse outcomes. Gut Liver 2014;8:248-53. [ Links ]

72. Grant DG, Bradley PT, Pothier DD, Bailey D, Caldera S, Baldwin DL, et al. Complications following gastrostomy tube insertion in patients with head and neck cancer: A prospective multi-institution study, systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2009;34:103-12. [ Links ]

73. Lee CG, Kang HW, Lim YJ, Lee JK, Koh MS, Lee JH, et al. Comparison of complications between endoscopic and percutaneous replacement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes. J Korean Med Sci 2013;28:1781-7. [ Links ]

74. Yagüe-Sebastián MM, Sanjuán-Domingo R, Villaverde-Royo MV, Ruiz-Bueno MP, Elías-Villanueva MP. Replacing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with the collaboration of the endoscopy and the primary care home care support teams. An efficient and safe experience. Semergen 2013;39:406-12. [ Links ]

75. Biswas S, Dontukurthy S, Rosenzweig MG, Kothuru R, Abrol S. Buried bumper syndrome revisited: A rare but potentially fatal complication of PEG tube placement. Case Rep Crit Care 2014;2014: 634953. [ Links ]

76. Khalil Q, Kibria R, Akram S. Acute buried bumper syndrome. South Med J 2010;103:1256-8. [ Links ]

77. Lee TH, Lin JT. Clinical manifestations and management of buried bumper syndrome in patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;68:580-4. [ Links ]

78. Müller-Gerbes D, Aymaz S, Dormann AJ. Management of the buried bumper syndrome: a new minimally invasive technique -the push method. Z Gastroenterol 2009;47:1145-8. [ Links ]

79. Born P, Winker J, Jung A, Strebel H. Buried bumper - The endoscopic approach. Arab J Gastroenterol 2014;15: 82-4. [ Links ]

80. Haslam N, Hughes S, Harrison RF. Peritoneal leakage of gastric contents, a rare complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1996;20:433-4. [ Links ]

81. Friginal-Ruiz AB, Gonzalez-Castillo S, Lucendo AJ. Endoscopic percutaneous gastrostomy: An update on the indications, technique and nursing care. Enferm Clin 2011;21:173-8. [ Links ]

82. Reising DL, Neal RS. Enteral tube flushing. Am J Nurs 2005;105:58-63. [ Links ]

83. Phillips NM, Nay R. A systematic review of nursing administration of medication via enteral tubes in adults. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:2257-65. [ Links ]

84. Tracey DL, Patterson GE. Care of Peg tube in the home. Home Healthcare Nurse 2006;24:381-6. [ Links ]

85. Blumenstein I, Shastri YM, Stein J. Gastroenterictubefeeding: Techniques, problems and solutions. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:8505-24. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Alfredo J Lucendo

Department of Gastroenterology

Hospital General de Tomelloso

Vereda de Socuéllamos, s/n

13700 Tomelloso, Ciudad Real. Spain

e-mail: alucendo@vodafone.es

Received: 19-08-2014

Accepted: 28-09-2014