Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.107 no.10 Madrid oct. 2015

Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Case report and review of the literature

Tumor fibroso solitario hepático. Descripción de un caso y revisión de la literatura

Natalia Bejarano-González1, Francisco Javier García-Borobia1, Andreu Romaguera-Monzonís1, Neus García-Monforte1, Joan Falcó-Fagés2, M. Rosa Bella-Cueto3 and Salvador Navarro-Soto4

1 Hepatobiliopancreatic Surgery Unit. Department of Surgery.

2 Department of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. UDIAT Centro Diagnóstico.

3 Department of Pathology. UDIAT Centro Diagnóstico.

4 Department of Surgery. Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí. Sabadell, Barcelona. Spain

ABSTRACT

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal tumor. Given its origin, it can appear in almost any location. In the literature, only 50 cases of SFT in the liver parenchyma have been reported. Despite its rarity, this entity should be included in the differential diagnosis of liver masses. We report the first case with imaging data from five years prior to diagnosis, which was treated by right portal embolization and arterial tumor embolization, and subsequent liver resection. We also present an exhaustive review of the cases described to date.

Key words: Liver solitary fibrous tumor. Mesenchymal neoplasia. Portal venous embolization. Transarterial embolization. Pre-surgical embolization. Review.

RESUMEN

El tumor fibroso solitario (TFS) es una neoplasia mesenquimal infrecuente. Dado su origen, puede aparecer en prácticamente cualquier localización. En la literatura sólo hay 50 casos descritos de TFS localizado en el parénquima hepático. A pesar de su rareza, debe ser considerada dentro del diagnóstico diferencial de una masa hepática. Presentamos el primer caso con seguimiento por imagen desde 5 años antes del diagnóstico, tratado mediante embolización portal derecha y embolización arterial tumoral con posterior resección hepática, así como una revisión exhaustiva de los casos descritos hasta la actualidad.

Palabras clave: Tumor fibroso solitario hepático. Neoplasia mesenquimal. Embolización portal. Embolización transarterial. Embolización prequirúrgica. Revisión.

Introduction

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal tumor. It was initially described in the pleura in 1931 by Klemperer and Rabin (1), and the pleura is the most common site.

Given its mesenchymal origin, it can appear in almost any location. It has been reported in the peritoneum, pericardium, thymus, orbit, meninges, spinal cord, and the parotid and thyroid glands (2). However, the location in the liver is particularly rare. Only 50 cases have been reported in the liver parenchyma (1-14).

Despite its rarity, SFT of the liver should be included in the differential diagnosis of hepatic mesenchymal tumors in adults along with leiomyoma, sclerosing hemangioma, inflammatory pseudotumor and sarcomas (2).

Here we report the case of a patient with liver SFT and review all the cases described to date.

Case report

79-year-old woman with a history of left nephrectomy for tuberculosis and a cystic lesion diagnosed in liver segment V by control computed tomography (CT) five years previously (Fig. 1). She consulted for presence of a mass and abdominal discomfort in the right upper abdominal quadrant. Physical examination revealed a large mass in the right hypochondrium causing local discomfort. Blood analysis revealed only a slight increase in alkaline phosphatase. Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT showed a solid, large, heterogeneous hepatic mass measuring 15.8x11.4 cm with thick, irregular contrast enhancement, occupying segments IV, V, VI and VIII and causing compression of neighboring structures (right kidney, head/body of the pancreas, duodenum, transverse colon and gallbladder) (Fig. 2).

For diagnostic purposes, ultrasound-guided percutaneous core biopsy of the lesion was performed. Histopathological study showed mesenchymal proliferation with rare atypia and a proliferative index (using Ki-67 immunohistochemical assay) below 1%. Vimentin, CD34 and bcl-2 were positive by immunohistochemistry, and actin, desmin, S-100, calretinin, c-kit, factor VIII, CD31 and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 were negative (Fig. 3).

A STF of the liver was suspected and the extension study was negative. Surgical resection of the lesion was indicated. Since the future liver remnant volume was considered insufficient, a right portal embolization was performed prior to surgical resection. Four weeks after embolization, the future liver remnant volume was 31%. On the day before surgery, selective arterial embolization was performed of the tumor-feeding branch of the right hepatic artery in order to minimize intraoperative bleeding (Fig. 4). Right hepatectomy extending to segment IV including the middle hepatic vein was performed without the need for the Pringle maneuver. Surgery was uneventful and postoperative evolution was correct and the patient was discharged on the sixth day (Figs. 5 and 6).

The final pathology examination of the specimen revealed a well delimited tumor measuring 18 cm in diameter, comprising tissue with a lobular appearance, with areas of homogeneous appearance and others fasciculated or myxoid, white or gray, with occasional cyst formation. The lesion was identified as a SFT with expansive margins, with around 5% of hypercellular areas, mild to moderate atypia, and occasional mitotic figures (< 1 mitosis/10 high power fields in hypercellular areas). Mean Ki-67 proliferative index was 12% in the hypercellular areas. The surgical resection margins were lesion-free. Focal changes were evident in the tumor and the adjacent parenchyma, attributable to the embolization (Fig. 7).

After a follow-up of 2 years and 7 months, the patient is currently disease-free.

Discussion

SFT is also known as localized fibrous mesothelioma, solitary mesothelioma, benign fibrous mesothelioma, localized fibroma, localized fibrous tumor or fibrous tumor of the pleura. These classifications are based on the histological characteristics and reflect the fact that the tumor is mainly located in the thoracic or pleural cavity (8,10). In the liver, the origin of this tumor maybe mesothelial, due to proliferation of Glisson's capsule, or conjunctive, in which case the origin is the intra-hepatic connective tissue. For this reason it may present as a pedunculated tumor or as an intraparenchymal mass (7).

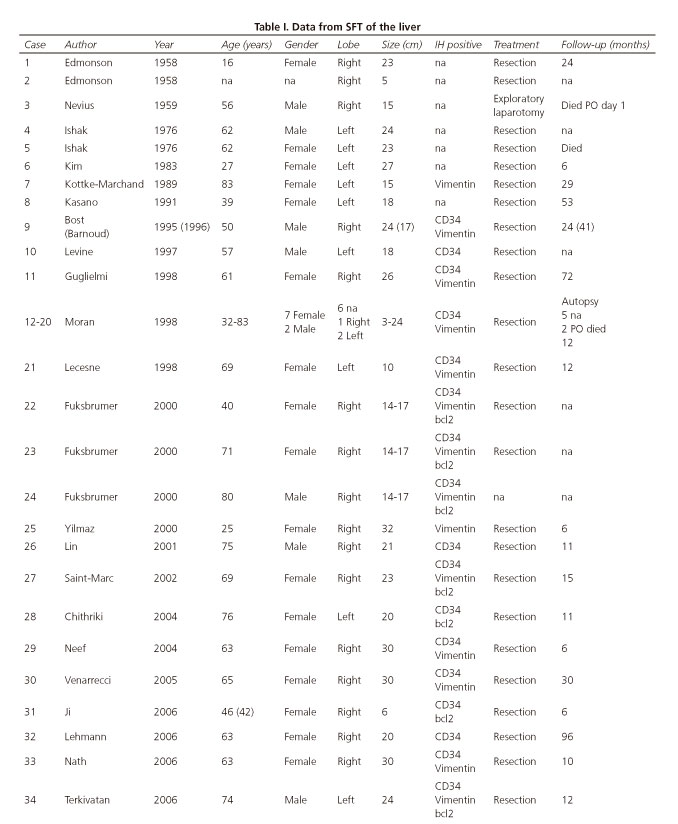

The real incidence of this type of tumor in the liver parenchyma is unknown. In the literature only 50 cases have been reported. The main characteristics of each clinical case are summarized in table I, which also displays data on the current case. SFT occurs more frequently in women (ratio 2:1). The average age of onset is 58 years (range 16-84 years). It is most often located in the right hepatic lobe and there are no cases reported in cirrhotic livers. The mean tumor diameter is 18.2 cm (range 1.5-30 cm).

Although some cases of malignancy have been reported (3,4,9), most are benign tumors with a progressive growth. In our case, for example, a liver cyst had been detected in the same location five years previously. Most cases are diagnosed at a late stage when they are already large, due to the mass effect they produce on adjacent organs. Other symptoms described include abdominal pain, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal distension, post-prandial fullness, weight loss, and fatigue, and in some cases SFT has been associated with hypoglycemia (2,9,11) or hypoglycemic coma (1). Indeed, non-islet cell tumor hypoglycemia (NICTH) syndrome has been described in some malignant tumors or in tumors of epithelial-mesenchymal origin (15). NICTH is believed to be secondary to the production and secretion of pro-insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) by the tumor. Medical treatment may suppress the tumor's secretion of pro-IGF2 and improve symptoms, although surgical resection is the best treatment for the syndrome and its underlying cause (9,13).

Except in these cases with low glycemia levels, biochemical laboratory tests of the liver tend not to present abnormalities, and tumor markers are also non-specific (8).

Although the typical radiological features are not present in all patients, most lesions are single, large, well-defined and heterogeneous.

Ultrasound reveals the lesions to be clearly defined hypo or hyperechoic masses, with or without calcification. On unenhanced CT they also appear as well-defined, with low density, with or without calcification, and may present cystic areas. After administration of intravenous contrast (arterial and portal phase) they appear as heterogeneous masses with multiple hypodense areas reflecting possible necrosis, and sometimes present minimal, irregular enhancement (11). MRI complements the study. On T1 and T2 sequences these tumors present low or intermediate intensity compared with normal liver parenchyma due to the high content of fibrous collagen tissue, the hypocellularity and the small number of mobile protons. The hyperintensity on the T2 sequences may be related to the necrosis, cystic or myxoid degeneration, vascular structures, and the hypercellular areas. After intravenous administration of gadolinium an intense heterogeneous enhancement is typically observed, which persists into the late phase (14,15). On PET-CT the tumor's glucose uptake has been described as heterogeneous, the greater the uptake, the more likely the tumor is to be malignant (14).

Other benign and malignant liver lesions may have similar radiological characteristics and so cannot be differentiated by imaging techniques. Although imaging tests are useful, the definitive diagnosis of SFT is based on histological examination. In spite of the possible advantages of percutaneous needle biopsy, some authors argue against its use because it may not confirm diagnosis and has been reported as a possible cause of tumor growth (13). In the pathology study, SFT usually presents as a low-grade neoplasm with proliferation of spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells. Mitotic figures, atypia and nuclear pleomorphism are occasionally observed. The cellularity is variable and is inversely related to the collagen content. Microscopically, a variety of architectural patterns can be seen. The most frequent is a random intermingling of tumor cells and collagen. Hypercellular areas alternate with hypocellular areas and hemangiopericytoma-like areas with the presence of staghorn vessels.

The immunohistochemical features are not specific to SFT, although typically these tumors are immunoreactive for CD34, vimentin and bcl-2. They do not express cytokeratins or S-100 (2). CD34 is a monoclonal antibody and a marker of pluripotent stem cells. A positive CD34 result can help to distinguish SFT from other spindle cell neoplasms such as neural tumor, fibrosarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, synovial sarcoma, mesothelioma or gastrointestinal stromal tumors (8).

Hypercellularity, high mitotic activity, tumor necrosis, cytologic anaplasia and/or nuclear atypia are suggestive of malignancy. The presence of metastatic lesions is indicative of malignancy too (6,12). In cases with mitotic index above 4/10 high power fields, local or distant recurrence is more frequent (5,6). Tumor size has also been reported to be a predictor of recurrence (8).

Whenever possible the treatment of choice is hepatic resection with clear margins. In most cases a major hepatectomy (resection of more than three liver segments) have to be performed. In cases with positive margins identified in the postoperative period, a re-resection is indicated (8).

It has been stated that liver transplantation may be an option in cases in which curative surgery cannot be afford (6). However, this procedure has not been described in any of the reported cases. In 2008 El-Khouli et al. described the first case of unresectable liver SFT treated only by transarterial chemoembolization with administration of cisplatin, doxorubicin and mitomycin C (10). Although they report that the tumor responded radiologicaly, they do not specify the follow-up time or survival. We report the first case that combines portal embolization and selective arterial embolization prior to radical surgery in order to prevent postoperative liver failure and to minimize intraoperative blood loss.

Other treatments such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy have not been proven as effective. They are reserved for cases in which surgical resection is incomplete or the pathology findings are suggestive of malignancy (5,6).

Local or distant recurrence rates of 15% have been reported for intra-thoracic SFT, and of 6% for extra-thoracic SFT (1,8). Only three cases of liver SFT with presence of recurrence have been reported: One case with bone metastases (4), other with liver recurrence and lung metastases (9) and third with local recurrence, brain and bone metastases (12).

However, the small number of patients diagnosed with liver SFT to date and the absence of long-term follow-up does not allow an accurate prognosis. Since these lesions are characterized by progressive local growth, the most important prognostic factor is resectability and the presence of tumor-free margins in order to prevent local or distant recurrence.

The follow-up of these patients is recommended. Brochard et al. suggests to follow the ESMO recommendations after surgical resection of soft tissue sarcomas (12).

Conclusion

SFT of the liver is a rare neoplasm whose incidence is currently unknown. However, it should be included in the differential diagnosis of a single, heterogeneous hepatic mass. Diagnosis is based on a correct interpretation of pathology and immunohistochemistry findings. The treatment of choice is surgical resection with free margins. Resectability is the most important prognostic factor, followed by pathology findings and tumor size.

Few cases have been diagnosed to date, but efforts should be made to identify them and follow them systematically in order to broaden our understanding of the behavior and prognosis of these tumors.

References

1. Famà F, Le Bouc Y, Barrande G, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver with IGF-II related hypoglycaemia. A case report. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008;393:611-6. DOI: 10.1007/s00423-008-0329-z. [ Links ]

2. Moran C, Ishak KG, Goodman ZD. Solitary fobrous tumor of the liver: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of nine cases. Ann Diagn Pathol 1998;2:19-24. DOI: 10.1016/S1092-9134(98)80031-2. [ Links ]

3. Fuksbrumer MS, Klimstra D, Panicek DM. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: Imaging findings. AJR 2000;175:1683-7. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.175.6.1751683. [ Links ]

4. Yilmaz S, Kirimlioglu V, Ertas E, et al. Giant solitary fibrous tumor of the liver with metastasis to the skeletal system successfully treated with trisegmentectomy. Dig Dis Sci 2000;45:168-74. DOI: 10.1023/A:1005438116772. [ Links ]

5. Neeff H, Obermaier R, Technau-Ihling K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the liver: Case report and review of the literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2004;389:293-8. DOI: 10.1007/s00423-004-0488-5. [ Links ]

6. Vennarecci G, Ettorre GM, Giovannelli L, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2005;12:341-4. DOI: 10.1007/s00534-005-0993-0. [ Links ]

7. Lehmann C, Mourra N, Tubiana JM, et al. Tumeur fibreuse solitaire du foie. J Radiol 2006;87:139-42. DOI: 10.1016/S0221-0363(06)73986-5. [ Links ]

8. Perini MV, Herman P, D'Alburquerque LAC, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: Report of a rare case and review of the literature. Int J Surg 2008;6:396-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.10.004. [ Links ]

9. Chan G, Horton PJ, Thyssen S, et al. Malignant transformation of a solitary fibrous tumor of the liver and intractable hypoglycemia. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007;14:595-9. DOI: 10.1007/s00534-007-1210-0. [ Links ]

10. El-Khouli RH, Geschwind JF, Bluemke DA, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation and treatment with transarterial chemoembolization. J Comput Assit Tomogr 2008;32:769-71. DOI: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181557453. [ Links ]

11. Taboada Rodríguez V, Zueco Zueco C, Sobrido Sanpedro C, et al. Tumor fibroso solitario hepático. Hallazgos radiológicos y revisión de la bibliografía. Radiología 2010;52:67-70. DOI: 10.1016/j.rx.2009.09.008. [ Links ]

12. Brochard C, Michalak S, Aubé C, et al. A not so solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Gastroentérol Clin Biol 2010;34:716-20. DOI: 10.1016/j.gcb.2010.08.004. [ Links ]

13. Liu Q, Liu J, Chen W, et al. Primary solitary fibrous tumors of liver: A case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol 2013;8:195. DOI: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-195. [ Links ]

14. Soussan M, Felden A, Cyrta J, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver. Radiology 2013;269:304-8. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.13121315. [ Links ]

15. Changku J, Shaohua S, Zhicheng Z, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver: Retrospective study of reported cases. Cancer Invest 2006;24:132-5. DOI: 10.1080/07357900500524348. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Natalia Bejarano González.

Hepatobiliopancreatic Surgery Unit.

Department of Surgery and Digestive Diseases.

Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí.

C/ Parc Taulí, s/n.

08208 Sabadell, Barcelona

e-mail: nbejaranog74@gmail.com

Received: 12-01-2015

Accepted: 02-02-2015

texto en

texto en