My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.108 n.2 Madrid Feb. 2016

REVIEW

Management of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy for endoscopic procedures: Introduction to novel oral anticoagulants

Manejo de la antiagregación y anticoagulación periendoscópica: introducción a antiagregantes y anticoagulantes orales más novedosos

Martha L. González-Bárcenas and Ángeles Pérez-Aisa

Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol. Marbella, Málaga. Spain

ABSTRACT

The development of novel antithrombotic therapy in the past few years and its prescription in patients with cardiovascular and circulatory disease has widened the spectrum of drugs that need to be considered when performing an endoscopic procedure. The balance between the thrombotic risk patients carry due to their medical history and the bleeding risk involved in endoscopic procedures should be thoroughly analyzed by Gastroenterologists. New oral anticoagulants (NOACs) impose an additional task. These agents, that specifically target factor IIa or Xa, do not dispose of an anticoagulation monitoring method nor have an antidote to revert their effect, just as with antiplatelet agents. Understanding the fundamental aspects of these drugs provides the necessary knowledge to determine the ideal period the antithrombotic therapy should be interrupted in order to perform the endoscopic procedure, offering maximum safety for patients and optimal results.

Key words: Antiplatelet therapy. Oral anticoagulants. Endoscopy.

RESUMEN

El desarrollo de novedosos fármacos antitrombóticos en los últimos años y su amplia prescripción en la población con patología cardiovascular y circulatoria ha ampliado el espectro de medicamentos que deben tenerse en cuenta a la hora de realizar un procedimiento endoscópico. La balanza entre el riesgo trombótico que presentan los pacientes debido a su patología subyacente y riesgo hemorrágico que conllevan algunas técnicas endoscópicas debe conocerse a fondo por parte de los gastroenterólogos. Los nuevos anticoagulantes orales suponen un reto adicional. Estos agentes, dirigidos específicamente frente a los factores IIa o Xa, no tienen métodos de monitorización del grado de anticoagulación ni antídoto que revierta su efecto, al igual que ocurre con los antiagregantes. Comprender aspectos claves de estos fármacos aportará los conocimientos necesarios para determinar el momento ideal de realización de la técnica y el tiempo de suspensión de los agentes antitrombóticos, con el fin de ofrecer la máxima seguridad para los pacientes y optimizar los resultados.

Palabras clave: Antiagregantes. Anticoagulantes orales. Endoscopia.

Introduction

The use of antithrombotic agents, including antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy, is a growing strategy worldwide. These types of drugs have experienced a rapid evolution in the past few years, with the development of newer formulas in a very short period of time with different mechanisms of action, which gastroenterologists must have in mind before performing an endoscopic procedure. Recently, Alberca de las Parras et al. (1) published a special article about the management of antithrombotic therapy for endoscopy, endorsed by four Spanish societies: Spanish Society for Digestive Pathology (Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva, SEPD), Spanish Society of Endoscopy (Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva, SEED), Spanish Society for Thrombosis and Hemostasis (Sociedad Española de Trombosis y Hemostasia, SETH), and Spanish Cardiology Society (Sociedad Española de Cardiología, SEC). In this article, available evidence about these drugs and recommendations of use in the perioendoscopic period are presented as a clinical practice guideline. Taking this guideline into consideration, along with other information from other societies worldwide, this article summarizes the most important factors to take into consideration for the management of antithrombotic agents in patients undergoing invasive procedures.

Thrombotic risk vs. bleeding risk

Determining the risk of thrombotic complications according to the underlying pathology of patients and comparing it with the risk of bleeding a specific procedures involves is fundamental to determine if antiplatelet therapy should be interrupted and for how long.

Assessment of thrombotic risk

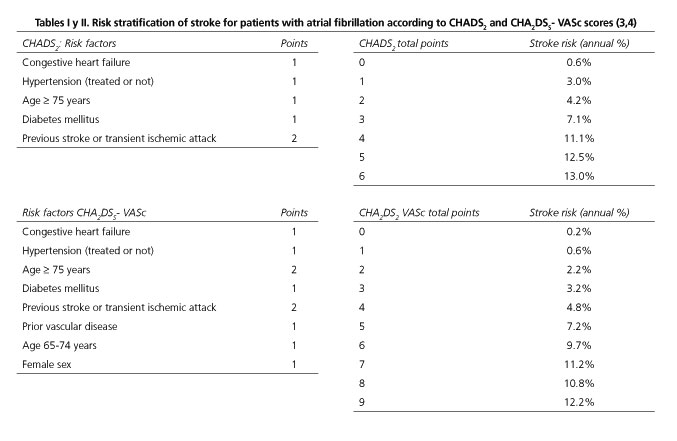

- Nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. The assessment of the thrombotic risk for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation is based on the CHADS2 or CHA2DS2-VASc scores (2), which are used to determine the risk of stroke in non-treated patients (3) (Tables I and II). Having at least one risk factor included in these scores is reason enough to indicate anticoagulant therapy (2), and the risk increases proportionately to the number of risk factors a patient has.

- Mechanic heart valves. The risk of thromboembolic events is determined by the location of the mechanic heart valve, the presence of atrial fibrillation, intracardiac thrombi, or history of thromboembolism. A low annual risk or thrombotic events (< 5%) is established for mechanical bileaflet aortic valve without any of the factors mentioned earlier (atrial fibrillation, intracardiac thrombi, or history of thromboembolism). A moderate risk (5-10%) is associated to atrial fibrillation. More than 10% of thromboembolic risk, or high risk, is considered in patients with mitral or tricuspid mechanic prosthesis, aortic mechanic valve different form bileaflet valve, or previous cardioembolic event (5).

- Cardiovascular disease: Coronary stents. Early interruption of double antiplatelet therapy in patients who have suffered cardiovascular disease with placement of coronary stents, especially drug-eluting stents (DES) which require at least a year of treatment, could lead to thrombosis of the stent and subsequent myocardial infarction. The risk increases in an inverse lineal relation with the time elapsed since the placement of the coronary stent and non-cardiac surgery (6), being highest during the first 6 weeks after placement of a bare-metal stent and within 3-6 months after treatment with a DES (7).

- Deep vein thrombosis. The risk of thromboembolic events is low (< 5%) 12 months after a primary event, increasing 5-10% if the time elapsed from the first thrombotic episode is between 3 and 12 months. A high risk (> 10%) is established during the first three months from the thrombosis or if an additional thrombophilic condition is present, including neoplasm, antiphospholipid syndrome, protein C, S, or antithrombin deficiency, or factor V Leiden homozygous mutation (8).

Assessment of bleeding risk

Although all endoscopic procedures carry a bleeding risk (low risk < 1%, high risk > 1%), this varies according to the type of procedure and if it is diagnostic or therapeutic. Table III summarizes the different procedures available and their bleeding risk according to the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Guideline published in 2009 for the management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures (9), while table IV organizes them according to the 2011 European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline about endoscopy and antiplatelet agents (10), and table V includes the classification established by the recently published article endorsed by diverse societies from Spain (SEPD, SEED, SETH y SEC) (1). This Spanish document and the ASGE Guideline are very similar in the classification established, distinguishing themselves from the ESGE guideline in two main factors: polypetomy, considered a high-risk bleeding technique for the ASGE and the Spanish Societies, is classified as a low-risk bleeding procedure if polyp size is < 10 mm according to de ESGE, and dilation of digestive stenoses, recognized as a low-risk bleeding procedure only by the ESGE. Recommendations for the management of anticoagulation for endoscopic procedures are based on retrospective studies as there are no randomized controlled trials up to date (11).

It is important to take into account additional risk factors for bleeding after a polypectomy, including age > 65 years old, polyp size ≥ 1 cm, cardiovascular disease, and, of course, antithrombotic therapy. Independently from polyp size, risk of bleeding does not increase with the use of neither non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) nor aspirin (10). According to de ESGE 2011 Guideline, clopidogrel does not increase the risk of bleeding for polypectomy < 10 mm (10). A recent meta-analysis which includes five studies that evaluated the risk of hemorrhage after polypectomy in patients taking clopidogrel has found a relevant increase in delayed bleeding, with a HR of 2.54 (CI 95% 1.68-3.84, p < 0.00001), but not for immediate bleeding. Polyp size was not considered during the analysis (12).

Patients who carry a greater hemorrhage risk because of their clinical history could benefit from prophylactic measures such as endoloop or endoclip after polypectomy, but there is no strong evidence to support this statement.

In order to make a correct decision in the periendoscopic period, evaluation of the pros and cons of the specific technique and of the interruption of antithrombotic therapy is fundamental in order to balance adequately bleeding and thrombotic risks. The cooperation between Cardiologists, Haematologists, and Endoscopists is essential for risk management in complex patients.

Anticoagulants and aniplatelets most used in clinical practice

Antiplatelet therapy

Antiplatelet agents inhibit platelet adhesion and aggregation to fulfill their role. There is no method for monitoring their function, and most of their action is irreversible, which is why it is necessary to wait for a renewal of the platelet population to eliminate the effect of these drugs.

Some of the main indications for antiplatelet agents include acute coronary syndromes, stable angina, percutaneous coronary therapy, revascularization surgery, ischemic stroke, and primary and secondary prophylaxis of atherosclerosis (13).

There is no consensus that states when to reintroduce these agents after an invasive procedure and the bleeding risk should be individualized. A systematic review recommends initializing aspirin 10 days after a polypectomy or 14 days after sphincterotomy if it is used for primary prophylaxis, and 7 days later if this drug is prescribed for secondary prophilaxis (14).

There is no evidence to support that double-platelet therapy is a contraindication for invasive procedures, although it seems reasonable to believe that the bleeding risk is incremented, which is why it should be avoided when possible. Alberca de las Parras et al. (1) state that, if the bleeding risk according to the procedure is low, double-platelet therapy could be maintained, but with a high bleeding risk procedure and with a low thrombosis risk for the patient, one of the antiplatelet agents should be interrupted (generally clopidogrel is interrupted and aspirin maintained). With high risk for both bleeding and thrombosis, endoscopic procedures should be withheld until the treatment can be modified if possible, or bridging therapy with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa could be an alternative (29). This last recommendation stated cannot be generalized as there is insufficient evidence available and it should be interpreted with caution and along with other specialists such as Cardiologists.

The main characteristics of the antiplatelet drugs most commonly used in clinical practice will be reviewed below: acetylsalicylic acid and thienopyridine agents.

Aspirin: acetylsalicylic acid

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, aspirin) is the most prescribed antiplatelet agent, widely used for cardiovascular disease, and the molecule which we understand the most. It irreversibly blocks platelet function as a cyclooxygenase1 (COX1) inhibitor by selectively blocking tromboxaneA2 (TXA2), which is why platelet renewal is necessary for eliminating its action (9). Low dosage of aspirin does not increment bleeding risk considerably for invasive procedures, making it unnecessary to interrupt in all cases (5), especially if a procedure carries a low bleeding risk. Multiple studies have analyzed the risk of bleeding after polypectomy while aspirin treatment is maintained, without observing significant increase of hemorrhage (10), making it unnecessary to interrupt.

Thienopyridines: clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor

Thienopyridines are adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists that stop selectively and irreversibly platelet activation and aggregation. They should be interrupted for all endoscopic procedures independently of the patient's thrombotic risk. If a patient has a high thrombotic risk, aspirin (i.e. 100 mg) could substitute thienopyridines during the periendoscopic period. Patients taking a double-platelet regimen should interrupt thienopyridines and maintain aspirin (9).

Clopidogrel is usually administered at a standard dose of 75 mg q.d., achieving 25-30% of irreversible platelet inhibition on the second day of administration, with a maximum effect between the 5th and 7th day of treatment. Higher dosing decreases the time needed for complete platelet inhibition (15). Platelet regeneration is achieved at a rate of 10-14% with each day of drug interruption (16).

Clopidogrel and ticagrelor (90 mg b.i.d) should be withheld 5 days prior to an endoscopic procedure, while prasugrel (10 mg q.d.) requires a 7-day interruption to assure platelet renewal because it has a rapid onset of action and is 10 to 100 times more potent than clopidogrel (17). Although ticagrelor has a quicker inhibiting effect than both clopidogrel and prasugrel, with a peak inhibition 2-4 hours after administration, its effect declines rapidly 72 hours after interruption, achieving nearly basal platelet function on the fifth day of suspension.

There is no antidote available for thienopyridines. If effect reversal is needed, platelet transfusion should be considered, assessing the bleeding risk the endoscopic procedures has: a high bleeding risk procedure requires > 50,000 platelets, while low bleeding risk procedures can be performed with > 20,000 (1). One platelet unit increments 5,000-10,000 platelets. In general, platelets are administered immediately before and during the endoscopic procedure (1U/10 kg) (1).

Oral anticoagulants

Dicoumarinic agents: acenocumarol and warfarin

Dicoumarinic agents are vitamin K antagonists, inhibiting vitamin K-dependant factors from the coagulation cascade (II, VII, IX, X, proteins C and S). Antithrombin is needed to complete their action. Monitorization is required with strict measurement of INR level due to its slow onset and offset of its effect and because of the narrow therapeutic margin it has, easily altered by other drugs or different types of food (18).

As with antiplatelet therapy, assessing thrombotic and bleeding risks is fundamental for their periendoscopic management. The ASGE Guideline (9) and the British Guideline (19) recommend maintaining anticoagulation for low bleeding risk procedures and interrupting otherwise. If a patient has a low thrombotic risk, interruption can me made 3 to 5 days prior to de endoscopy, in order to achieve INR < 1.5. Bridging therapy with low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) is recommended if high risk for thrombosis is present. LMWH should be administered 2 days after interrupting acenocumarol or warfarin, with the last administration at least 8 hours before the procedure (or preferably omitting the dose on the day of the procedure). After the procedure, LMWH are maintained while reintroduction of the oral anticoagulant is performed until INR is in therapeutic range.

Before a non-deferrable endoscopy is performed, such as an urgent endoscopy, anticoagulation must be reverted to obtain a safe INR margin between 1.5 and 2.5 (1). Considering the clinical history of the patient to avoid volume overload or increased risk for thrombosis, the first step for reversion is with vitamin K (Fitometadiona (Spain) 10 mg in 100 mL of saline solution at 0.9% or glucose solution at 5%, administering 10 ml in the first 10 minutes and the rest in 30 minutes, with an initial effect 6 hours after infusion and ending 12 hours after administration). If necessary, the next recommended step for reverting anticoagulation is the administration or Prothrombin Complex Concentrates (Beriplex® 500 UI, Optaplex®, Prothromplex Immuno Tim 4,600 UI® are available in Spain), never forgetting its thrombogenic effect. The dose is calculated with the following formula: (target prothrombin time- measured prothrombin time) x weight (kg) x 0.6 (1).

Other reversal agents that can be used include recombinant factor VII and fresh-frozen plasma, but only in specific scenarios. Recombinant factor VII (Novoseven® 1.2 mg vial administered at 90 µg/kg) should only be given to patients with hemophilia with inhibitors, acquired hemophilia, or severe congenital factor VII deficiency due to its high thrombophilic power (1). Fresh-frozen plasma is only indicated when other therapies have failed or are not available, at a dose of 10 to 30 ml/kg (1).

New oral anticoagulants (NOAC): dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban

This group of anticoagulants has demonstrated in clinical trials to be superior to warfarin in prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation and systemic embolic events, reason why its prescription is expected to expand in the years to come. NOACs have a direct effect that do not need of prothrombin as a mediator for their effect. Monitorization is not required as with warfarin because they have a more stable action. Compared to warfarin, the onset and offset of the anticoagulant effect after administration is faster. NOACs differ in their mechanism of action and pharmacokinetic characteritics (20).

On the other hand, the risk of bleeding with these novel anticoagulants is not related with alteration of the available coagulation parameters for monitorization and there are no specific antidotes for reverting their effect. In bleeding situations, and depending on its severity, Alberca de las Parras et al. (1) state that platelet transfusion should be considered if the patient has less than 60.000 platelets, renal function must be observed if dabigatran is the NOAC administered because its circulating levels are the most affected during renal failure, and, if necessary, the use of prothrombin complex concentrates for anticoagulation reversion.

Dabigatran

The anticoagulant effect for dabigatran is achieved through direct thrombin (factor IIa) inhibition, with a mean half-life of 9 to 17 hours, according to age and renal function (21). Its maximum activity is achieved 0.5-2 hours after administration. Dabigatran is a prodrug prescribed b.i.d. which is absorbed in the proximal small bowel and eliminated though renal excretion.

The risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation is estimated to be between 0.3 and 0.5% annually without anticoagulation (22). A significantly greater risk has been observed for dabigatran at a dose of 150 mg b.i.d. compared to warfarin (1.85% vs. 1.36%/year; p = 0.002; HR 1.49 [1.21-1.84]) (23,24), which is equivalent 5 additional events per every 1,000 patients per year, probably due to direct luminal injury produced by the non-absorbed active drug.

Coagulation parameters can be altered while taking dabigatran. Thrombin time (TT) is the most frequently altered, followed by activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). Prothrombin time is not altered with this agent.

There is no consensus on when to interrupt the treatment before an invasive procedure for NOACs. The European Society of Anesthesiology (ESA) states that these drugs should not be interrupted for diagnostic gastroscopies or colonoscopies with or without biopsy (without polypectomy) (25). Desai et al. (21) recommend that these low-bleeding risk procedure be performed during the lowest effect of the drug, which translates to 10 hours after the administration for NOACs taken b.i.d (dabigatran and apixaban) and 20 hours for rivaroxaban which is take only once a day.

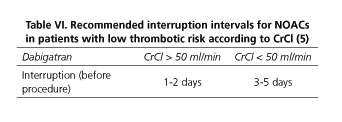

Creatinine clearance (CrCl) determines the moment of interruption for dabigatran if a high-bleeding risk procedure is to be performed: for CrCl ≥ 50 ml/min, withhold 1-2 days; for < 50 ml/min, withhold 3-5 días (5) (Table VI). Alberca de las Parras et al. (1) are in agreement with this recommendation, but establish at least 2 day of suspension independently of the CrCl, 3 days if CrCl is between 50 and 80 ml/min, and 4 days for CrCl 30-50ml/min (Table VII). Reintroduction should be done the day after the procedure.

For patients with high thrombotic risk, bridging therapy with LMWH can be an option similar to warfarin in patients with CrCl > 50 ml/min (20,25) (Table VIII). If the interruption is adjusted to CrCl, overtreating or undertreating will be avoided (1). The dose of LMWH is not well established. High therapeutic dose of LMWH has not demonstrated to be superior to low prophylactic dose, although bleeding seems to increase wit the first option (19).

Controversy also surrounds the moment of reintroduction of dabigatran and of NOACs in general after a surgical or endoscopic procedure. In theory, anticoagulation should be administered when hemostasis is assured and partial healing is achieved (9). The use of mechanical methods such as endoclip or endoloop after a polypectomy could reduce de risk of post-procedural bleeding in these patients, but there is no sustainable evidence to support this statement as an official recommendation. Due to NOACs rapid onset of their effect, only hours after being administered, withholding these drugs 24 to 48 hours after a high bleeding risk procedure can be an option, or if bridging therapy has been prescribed, LMWH could be maintained until the oral anticoagulant is reintroduced (20). Delayed bleeding is a risk up to 14 days after the procedure which increases when anticoagulation is reintroduced.

As mentioned before, no specific antidote is available for reverting anticoagulation. In case of severe bleeding, the use of recombinant factor VII or even hemodialysis can be considered (5).

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban is a direct factor Xa inhibitor, attenuating thrombin formation. It is absorbed in the proximal small intestine without interacting with food. Its half-life is 5 to 9 hours in younger patients and 11 to 13 hours in the elderly (15). It is partially excreted through urine and the rest is metabolized by the liver, which is why it is contraindicated in patients with advanced liver disease and severe renal insufficiency (26). It is administered in a single daily dose.

As with dabigatran, increased upper gastrointestinal bleeding was observed compared to warfarin in clinical trials (2% vs. 1.24%/year; Hazard ratio [HR] 1.61 [CI 1.30-1.99]), resulting in 8 additional events per 1000 patients per year (27).

Coagulation parameters (prolonged PT and aPTT) can be altered although there is no relation between their levels and the risk of hemorrhage.

In case interruption is needed, the publication endorsed by diverse societies from Spain (SEPD, SEED, SETH and SEC) establishes that withholding rivaroxaban for 2 days is enough for a safe endoscopic procedure to be performed, without considering CrCl (1). This is possible if CrCl is > 50 ml/min (25). The reintroduction is advised for the day after the endoscopy. A document that summarizes the main characteristic of NOACs states that CrCl is fundamental to determine the time this drug must be interrupted: 1 day if CrCl >90 ml/min, 2 days if CrCl 60-90 ml/min, 3 days for CrCl 30-59ml/min, and 4 days if CrCl 15-29 (5) (Table IX). Bridging therapy with LMWH could be considered as with dabigatran for patients with high thrombotic risk.

In case of severe hemorrhage, prothrombin complex concentrate can be administered, but effectiveness is not guaranteed (15).

Apixaban

Apixaban is a direct factor Xa inhibitor administered b.i.d. which is absorbed in the small bowel with a greater liver metabolism than rivaroxaban. Thirty-five percent of the drug is excreted through feces without previous absorption, and only ¼ is excreted by the kidneys (21), which is why it is also not recommended in advanced liver disease or in severe kidney disease. It has a half-life of 8 to 15 hours, with a maximum plasma concentration 3 to 4 hour after administration (20).

Different from dabigatran and rivaroxaban, apixaban has shown to have less bleeding risk than warfarin, although the results are not statistically significant (0.76% vs. 0.86%/ year; HR 0.89 [CI 0.7-1.15]; p = 0.73) (21).

Coagulation monitorization times are altered similarly to rivaroxaban and should have the same interpretation. Interruption is also similar to rivaroxaban according to CrCl (5) (Table IX). Spanish societies (SEPD, SEED, SETH and SEC) establish a standard interruption time 2 days before an endoscopic procedure with high risk of bleeding and reintroduction the day after (1).

As with rivaroxaban, prothrombin concentrate complex can be considered for severe uncontrollable bleeding (15).

Conclusion

An increased prescription of the most novel antithrombotic therapy available is foreseeable in the years to come, especially in the elderly population with cardiovascular disease, in many occasions associated to other comorbidities. This makes it necessary for Gastroenterologists to understand the main characteristics of these drugs, including their gastrointestinal security profile, in order to manage them adequately in the periendoscopic period. Assessing the risk for thrombosis when withholding antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy along with the potential bleeding risk an endoscopic procedure carries, and always taking into consideration if the procedure can be delayed or not, will be fundamental for taking the most certain decision.

For patients taking transient anticoagulant therapy, it is advisable to wait for the treatment to end when possible in order to decrease the risk for complications. If this is not possible or if the treatment is prescribed chronically, cooperation between Cardiologists, Hematologists, and Gastroenterologists will offer the best options to manage antithrombotic therapy in these more complicated situations.

For these reasons, it is mandatory for international societies to establish clinical guidelines to optimize the interruption and reintroduction of antithrombotic therapy in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures, especially for the management of NOACs. Alberca de las Parras et al. (1) have recently published a multidisciplinary document elaborated by specialists from Spanish societies including the Spanish Society for Digestive Pathology (Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva, SEPD), the Spanish Society of Endoscopy (Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva, SEED), the Spanish Society for Thrombosis and Hemostasis (Sociedad Española de Trombosis y Hemostasia, SETH), and the Spanish Cardiology Society (Sociedad Española de Cardiología, SEC), a document that serves as a guideline for the adequate use of these drugs in clinical practice. Also, the development of clinical trials to understand to the fullest the physiopathology of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking NOACs is fundamental in order to develop an antidote to revert anticoagulation.

References

1. Alberca de las Parras F, Marín F, Roldán Schilling V, et al. Manejo de los fármacos antitrombóticos asociado a procedimientos endoscópicos. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2015;107:289-306. [ Links ]

2. Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest 2010;137:263-72. DOI: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [ Links ]

3. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182 678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J 2012; 33:1500 DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr488. [ Links ]

4. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369-429. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [ Links ]

5. Baron TH, Kamath PS, McBane RD. Management of antithrombotic therapy in patients undergoing invasive procedures. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2113-24. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1206531. [ Links ]

6. Kleiman NS. Grabbing the horns of a dilemma: the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after stent implantation. Circulation 2012;125:1967-70. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.102335. [ Links ]

7. Van Kuijk JP, Flu WJ, Schouten O, et al. Timing of noncardiac surgery after coronary artery stenting with bare metal or drug-eluting stents. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:1229-34. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.038. [ Links ]

8. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141:2(Supl.):e419S-e494S. (Erratum, Chest 2012; 142:1698-1704.) DOI: 10.1378/chest.11-2301. [ Links ]

9. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, et al. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:1060-70. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.040. [ Links ]

10. Boustière C, Veitch A, Vanbiervliet G, et al, European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Endoscopy and antiplatelet agents. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2011;43:445-61. DOI: 10.1055/s-0030-1256317. [ Links ]

11. Andreu García M. Manejo de la anticoagulación en la endoscopia terapéutica. GH continuada 2010;9:302-5. [ Links ]

12. Gandhi S, Narula N, Mosleh W, et al. Meta-analysis: colonoscopic pst-polypectomy bleeding in patients on continued clopidogrel therapt. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:947-52. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12292. [ Links ]

13. Sierra P, Gómez-Luque A, Castillo J, et al. Guía de práctica clínica sobre el manejo perioperatorio de antiagregantes plaquetarios en cirugía no cardiaca (Sociedad Española de Anestesiología y Reanimación). Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2011;58(Supl. 1):1-16. DOI: 10.1016/S0034-9356(11)70047-0. [ Links ]

14. Kimchi NA, Broide E, Scapa E, et al. Antiplatelet therapy and the risk of bleeding induced by gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. A systematic review of the literature and recommendations. Digestion 2007;75:36-45. DOI: 10.1159/000101565. [ Links ]

15. Baron TH, Kamath PS, McBane RD. New anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents: a primer for the gastroenterologist. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:187-95. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.020. [ Links ]

16. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. American Collegeof Chest Physicians. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (erratum in: Chest 2012;141:1129). Chest 2012;141(Supl.):e326S-e350S. DOI: 10.1378/chest.11-2298. [ Links ]

17. Hall R, Mazer CD. Antiplatelet drugs: a review of their pharmacology and management in the perioperative period. Anesth Analg 2011;112:292-318. DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318203f38d. [ Links ]

18. Soff GA. A new generation of oral direct anticoagulants. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012;32:569-74. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242834. [ Links ]

19. Veitch AM, Baglin TP, Gershlick AH, et al. Guidelines for the management of and antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing anticoagulant endoscopic procedures. Gut 2008;57:1322-9. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2007.142497. [ Links ]

20. Llau JV, Ferrandis R, Castillo J, et al.; participantes en el Foro de Consenso de la ESRA-España sobre "Fármacos que alteran la hemostasia". Manejo de los anticoagulantes orales de acción directa en el periodo perioperatorio y técnicas invasivas. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2012;59:321-30. DOI: 10.1016/j.redar.2012.01.007. [ Links ]

21. Desai J, Granger CB, Weitz JI, et al. Novel oral anticoagulants in gastroenterology practice. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;78:227-39. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.179. [ Links ]

22. Coleman CI, Sobieraj DM, Winkler S, et al. Effect of pharmacological therapies for stroke prevention on major gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:53-63. DOI: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02809.x. [ Links ]

23. Eikelboom JW, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, et al. Risk of bleeding with 2 doses of dabigatran compared with warfarin in older and younger patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation 2011;123:2363-72. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.004747. [ Links ]

24. FDA Advisory Committee. Dabigatran briefing document (Boehringer Ingelheim). Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee (FDA). 2010:1-168. [ Links ]

25. Kozek-Langenecker SA, Afshari A, Albaladejo P, et al. Management of severe perioperative bleeding: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013;30:270-382. DOI: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835f4d5b. [ Links ]

26. Peacock WF, Gearhart MM, Mills RM. Emergency management of bleeding associated with old and new oral anticoagulants. Clin Cardiol 2012;35:730-7. DOI: 10.1002/clc.22037. [ Links ]

27. Nessel C, Mahaffey K, Piccini J, et al. Incidence and outcomes of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with rivaroxaban or warfarin: results from the ROCKET AF trial. Chest J (Internet) 2012 Accessed Dec 4, 2012;142 (4_MeetingAbstracts):84A. DOI: 10.1378/chest.1388403. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Martha L. González Bárcenas.

Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Agencia Sanitaria Costa del Sol.

Autovía A7, km. 187.

29600 Marbella, Málaga. Spain

e-mail: marthalgb@gmail.com

Received: 16-04-2015

Accepted: 07-07-2015

text in

text in