Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.108 no.6 Madrid jun. 2016

Clinical Practice Guideline: Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and functional constipation in the adult

Guía de Práctica Clínica: Síndrome del intestino irritable con estreñimiento y estreñimiento funcional en adultos

Fermín Mearin1, Constanza Ciriza2, Miguel Mínguez3, Enrique Rey4, Juan José Mascort5, Enrique Peña6, Pedro Cañones7 and Javier Júdez8, on behalf of the Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva (SEPD), Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria (semFYC), Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria (SEMERGEN) and Sociedad Española de Médicos Generales y de Familia (SEMG)

1 Coordinator of the CPG. Roma IV Bowel Disorders Committee. Member of AEG. Centro Médico Teknon. Barcelona, Spain.

2 Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Group. SEPD. Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre. Madrid, Spain.

3 Member of AEG and SEPD. Hospital Clínico Universitario. Universitat de Valencia. Valencia, Spain.

4 SEPD. Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos. Madrid, Spain.

5 Scientific Department. semFYC.

6 Coordinator. Digestive Diseases. SEMERGEN.

7 Coordinator. Digestive Diseases. SEMG.

8 Knowledge Management Department. SEPD

ABSTRACT

In this Clinical Practice Guideline we discuss the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of adult patients with constipation and abdominal complaints at the confluence of the irritable bowel syndrome spectrum and functional constipation. Both conditions are included among the functional bowel disorders, and have a significant personal, healthcare, and social impact, affecting the quality of life of the patients who suffer from them. The first one is the irritable bowel syndrome subtype, where constipation represents the predominant complaint, in association with recurrent abdominal pain, bloating, and abdominal distension. Constipation is characterized by difficulties with or low frequency of bowel movements, often accompanied by straining during defecation or a feeling of incomplete evacuation. Most cases have no underlying medical cause, and are therefore considered as a functional bowel disorder. There are many clinical and pathophysiological similarities between both disorders, and both respond similarly to commonly used drugs, their primary difference being the presence or absence of pain, albeit not in an "all or nothing" manner. Severity depends not only upon bowel symptom intensity but also upon other biopsychosocial factors (association of gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms, grade of involvement, and perception and behavior variants). Functional bowel disorders are diagnosed using the Rome criteria. This Clinical Practice Guideline has been made consistent with the Rome IV criteria, which were published late in May 2016, and discuss alarm criteria, diagnostic tests, and referral criteria between Primary Care and gastroenterology settings. Furthermore, all the available treatment options (exercise, fluid ingestion, diet with soluble fiber-rich foods, fiber supplementation, other dietary components, osmotic or stimulating laxatives, probiotics, antibiotics, spasmolytics, peppermint essence, prucalopride, linaclotide, lubiprostone, biofeedback, antidepressants, psychological therapy, acupuncture, enemas, sacral root neurostimulation, surgery) are discussed, and practical recommendations are made regarding each of them.

Key words: Irritable bowel syndrome. Constipation. Abdominal discomfort. Adults. Primary care. Digestive diseases. Clinical practice guideline.

RESUMEN

En esta Guía de Práctica Clínica analizamos el manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico de pacientes adultos con estreñimiento y molestias abdominales, bajo la confluencia del espectro del síndrome del intestino irritable y el estreñimiento funcional. Ambas patologías están encuadradas en los trastornos funcionales intestinales y tienen una importante repercusión personal, sanitaria y social, afectando a la calidad de vida de los pacientes que las padecen. La primera es el subtipo de síndrome del intestino irritable en el que el estreñimiento es la alteración deposicional predominante junto con dolor abdominal recurrente, hinchazón y distensión abdominal frecuente. El estreñimiento se caracteriza por la dificultad o la escasa frecuencia en relación con las deposiciones, a menudo acompañado por esfuerzo excesivo durante la defecación o sensación de evacuación incompleta. En la mayoría de los casos no tiene una causa orgánica subyacente, siendo considerado un trastorno funcional intestinal. Son muchas las similitudes clínicas y fisiopatológicas entre ambos trastornos, con respuesta similar del estreñimiento a fármacos comunes, siendo la diferencia fundamental la presencia o ausencia de dolor, pero no de un modo evaluable como "todo o nada". La gravedad de estos trastornos depende no sólo de la intensidad de los síntomas intestinales sino también de otros factores biopsicosociales: asociación de síntomas gastrointestinales y extraintestinales, grado de afectación, y formas de percepción y comportamiento. Mediante los criterios de Roma, se diagnostican los trastornos funcionales intestinales. Esta Guía de Práctica Clínica está adaptada a los criterios de Roma IV difundidos a finales de mayo de 2016 y analiza los criterios de alarma, las pruebas diagnósticas y los criterios de derivación entre Atención Primaria y Aparato Digestivo. Asimismo, se revisan todas las alternativas terapéuticas disponibles (ejercicio, ingesta de líquidos, dieta con alimentos ricos en fibra soluble, suplementos de fibra, otros componentes de la dieta, laxantes osmóticos o estimulantes, probióticos, antibióticos, espasmolíticos, esencia de menta, prucaloprida, linaclotida, lubiprostona, biofeedback, antidepresivos, tratamiento psicológico, acupuntura, enemas, neuroestimulación de raíces sacras o cirugía), efectuando recomendaciones prácticas para cada una de ellas.

Palabras clave: Síndrome del intestino irritable. Estreñimiento. Molestia abdominal. Adultos. Atención primaria. Enfermedades digestivas. Guía de práctica clínica.

Conceptual aspects, impact and pathophysiology

1. Why are irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and functional constipation in the adult jointly approached?

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional constipation (FC) are two functional bowel disorders (FBDs) (1,2). Therefore, both conditions have in common that their cause is not explained by morphological, metabolic or neurological changes that may be shown by routine diagnostic techniques. IBS may be divided, according to the predominant bowel habit change, into IBS with constipation (IBS-C) and IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D); when both change types (constipation and diarrhea) alternate, the condition is referred to as mixed-type IBS (IBS-M), and when bowel habit lies somewhere between constipation and diarrhea the condition is denoted indeterminate IBS (IBS-I) (1,2).

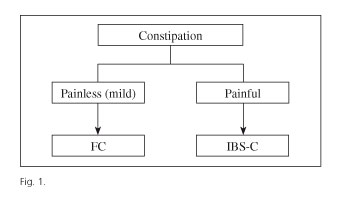

While IBS-C and FC are different FBDs from a conceptual perspective, they may in practice become very similar, even indistinguishable conditions (3-5). In both, constipation is the primary symptom, in association with abdominal bloating/distension. The presence of abdominal pain more than once a week and the temporal relationship of pain with defecation theoretically differentiate IBS-C from FC (1). However, patients with FC may feel some pain, and it is not always easy to determine temporal relationships (3). In fact, IBS-C and FC are part of a spectrum where patients with severe abdominal pain and constipation are on one end, and patients with constipation and no pain at all are on the other end; in practice, most cases fall somewhere in between. More rationally, this type of FBD could perhaps be classified as follows: painful constipation (similar to IBS-C) and unpainful constipation (similar to FC) (Fig. 1).

In addition to the above conceptual and clinical similarities, IBS-C and FC share several pathogenic mechanisms, and both have responded favorably to the same drugs (6-11).

All the above led us to develop a set of CPG to jointly approach IBS-C and FC. Doubtless, both conditions share more similarities than differences.

2. What is irritable bowel syndrome?

IBS is characterized by the presence of recurrent abdominal pain associated with bowel habit changes, whether in the form of constipation or diarrhea or combining both; bloating and abdominal distension are very common in IBS (1,2). According to the Rome IV criteria (2), IBS is diagnosed based on the presence of recurrent abdominal pain, which must be present for at least one day weekly, with two or more of the following characteristics: a) it is associated with defecation; b) it relates to a change in bowel movement frequency; and c) it is linked to a change in stool consistency. As per duration requirements, these criteria must have been met for the past three months, and symptoms must have had their onset at least six months prior to the diagnosis (1,2).

The overlapping of IBS with other FBDs (such as FC or functional diarrhea), other functional digestive extraintestinal disorders (such as functional dyspepsia or functional heartburn), or other non-digestive disorders (such as fibromyalgia or interstitial cystitis) is very common (12,13).

The diagnosis should be based on the characteristic symptoms systematized by the Rome IV criteria (Tables I and II, algorithm 1), but this is no excuse to do without the pertinent examinations to establish a differential diagnosis with some organic conditions that may have similar manifestations.

3. What is irritable bowel syndrome with constipation?

IBS-C is the IBS subtype where constipation is the predominant bowel habit. Stool characteristics allow to categorize IBS into subtypes using the Bristol Stool Scale (14) (Fig. 2). According to the proportion of each fecal type during the days when feces are abnormal IBS may be determined to be IBS-C, IBS-D or IBS-M. For IBS-C, over 25% of bowel movements should involve type-1 or type-2 stools, with fewer than 25% resulting in type-6 or type-7 stools (1,2) (Table I).

4. What is functional constipation?

Constipation is characterized by difficulty in passing stools or a low frequency of bowel movements, often accompanied by straining during defecation or a feeling of incomplete evacuation (1,2). In most cases no underlying physical cause is to be found, and the condition is considered as a FBD. According to the Rome IV criteria (Table II), FC is defined as the presence of two or more of the following during the previous 3 months: a) defecatory straining (≥ 25% bowel movements); b) hard or lumpy stools (≥ 25% bowel movements); c) a feeling of incomplete evacuation (≥ 25% bowel movements); d) defecatory obstruction (≥ 25% bowel movements); e) manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation (≥ 25% bowel movements); and f) fewer than 3 spontaneous complete bowel movements per week. Symptoms must be present for at least 6 months before the diagnosis, diarrhea must not be present except after using a laxative, and IBS criteria must not be met (1).

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) prefers a simpler though highly similar definition: "Unsatisfactory defecation characterized by infrequent stools, difficult stool passage or both for at least 3 months. Difficult stool passage includes straining, a sense of incomplete evacuation, hard/lumpy stools, prolonged time to pass stool, or need for manual maneuvers to pass stool" (15).

However, these definitions have been established through medical consensus and expert opinions, and the views of patients regarding their constipation are also important. Thus, in a population-based study in the USA, the complaints reported by a total of 557 subjects were as follows: 79% straining, 74% gas, 71% hard feces, 62% abdominal discomfort, 57% unfrequent stools, 57% abdominal distension, and 54% sensation of incomplete evacuation (16).

5. What similarities and differences are there between irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and functional constipation?

As discussed above, there are many clinical similarities between IBS-C and FC: they are more common in people with similar characteristics (middle-aged women), constipation is obviously present (also abdominal bloating/distension), and the latter's response to commonly-used drugs is also similar. Importantly, constipation is similarly characterized for both these FBDs (3). The key difference between both lies in the presence or absence of pain, but again this is an inconsistent finding that cannot be assessed on an all-or-nothing basis.

As regards the pathophysiology, constipation causes are also common to both conditions: colonic motility changes, difficulty in expelling stools, insufficient abdominal press function, and a combination of the above. None of the aforementioned causes, however, may be identified in a significant number of (particularly IBS-C) cases.

The crucial pathophysiological difference may well lie in different visceral sensitivities: colonic hypersensitivity is more common in IBS, and rectal hyposensitivity is more often seen in FC (17-19).

6. What is the clinical, social, and financial significance of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and functional constipation?

Some physicians consider IBS-C and FC to be trivial conditions, but their personal, healthcare, and social impact is highly significant. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is considerably impaired in patients with IBS, as shown by relevant reviews (20,21). IBS-related costs, in turn, are also significant. Suffice it to say that 3.5 million people visit doctors for this problem each year in the USA, which represents a yearly cost of 20,000 million USD (22). Data obtained from Europe, specifically from Spain, also show an increase in both direct and indirect costs for patients with IBS-C (23).

Regarding the impact of FC on the daily lives of patients, 69% consider it impairs their academic or occupational performance (16), the condition being a relevant cause of absenteeism in severe cases (mean loss of 2.4 activity days/month), and of reduced productivity (16).

Other studies have confirmed the condition's social impact on comparing FC patient data to the general population (24). All this carries an enormous health care cost, both direct and indirect, for FC. In the USA, FC accounts for approximately 2.5 million visits and 92,000 hospitalizations yearly, with a cost of nearly 7,000 million USD in diagnostic assessments (24,25).

The findings of a systematic review in 2010 may well illustrate the HRQoL issue in FC. Ten studies were identified that used various generic health questionnaires: seven used the SF-36 (Short-Form 36), two the PGWBI (Psychological General Well Being Index), and one the SF-12 scales (26). Virtually all SF-36 domains were impaired in FC patients as compared to healthy controls; as expected, differences were greater for patients cared for in the outpatient versus the inpatient setting.

When the HRQoL of patients with constipation is compared to that of patients with other common conditions the results are amazing (26). The impact of FC on physical aspects is greater for patients requiring specialist care than for patients with ulcerative colitis (stable or otherwise), stable Crohn's disease, or other non-digestive conditions such as chronic allergy or back pain.

7. How can the severity of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and of functional constipation be established?

Severity in FBDs, including IBS and FC, not only depends on intestinal bowel symptoms' intensity but also on other biopsychosocial factors (association of gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms, grade of impairment, and perception and behavior variants). Thus, both visceral and central physiological factors play a role in IBS severity. Severity, in turn, directly impacts quality of life, and must be considered in the making of diagnostic and therapeutic decisions (27,28).

Severity in IBS, as well as in other FBDs, is usually established in two ways: a) using an individual symptom scale (e.g., mild, moderate, severe, extreme); or b) using a combination of various symptoms or attitudes (e.g., abdominal pain together with stool frequency and consistency, defecatory urgency, impact on quality of life, usage of health care resources, disability level).

The Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS) is the questionnaire most widely used for the assessment of IBS severity (29). It surveys the intensity of 5 different items along 10 days: abdominal pain, distension, stool frequency, stool consistency, and interference with daily activities. Each item is scored on 0-to-100 visual analog scale, and all 5 scores are then added up. The IBS-SSS tool has been translated into Spanish and validated (30).

Diagnosis

8. How many pathophysiological types of functional constipation (with or without irritable bowel syndrome) are there?

FC is classified according to the pathophysiological mechanism involved in three catergories (1,31-34).

1. Patients with functional defecatory disorders (Table III): impaired rectal emptying from inadequate rectal propulsion or abnormal relaxation in the striated muscle responsible for opening the anal canal (relaxation deficiency, paradoxical contraction or dyssynergic defecation) may be detected. Both dysfunctions may be associated and often result in diminished rectal sensitivity (hyposensitivity), structural pelvic floor defects (excessive perineal descent, rectocele, enterocele, intussusception, etc.) or in colonic motor disorders with delayed colonic transit time (CTT) (32).

2. Patients with slow colonic transit (SCT), where the time it takes the intestinal material to pass through the colon is longer than normal.

3. Patients with normal colonic transit (NCT). Diagnosing these pathophysiological subtypes requires functional diagnostic techniques that must be carried out in specialist centers.

Which functional studies allow to establish a diagnosis of defecatory dysfunction? Where and in which order should they be performed?

Three examination techniques help provide a diagnosis. While no consensus exists to unify their method, the presence of ineffective evacuation should be ascertained using at least two techniques (32).

Given its accessibility, simplicity, cost, absence of side effects, and diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, the balloon expulsion test must come always first (32,34-36). While no specialist facility is needed, its performance is challenging in a Primary Care or specialist outpatient setting. This test assesses a patient's ability to expel, under intimacy conditions, a water-filled balloon at body temperature and with enough volume to induce an urge to defecate. Expulsion within up to 1-2 minutes is deemed normal. In a non-controlled study of patients with FC this test was useful to identify defecatory dysfunction, with a sensitivity and specificity of 87.5% and 89%, respectively, and with a positive predictive value and a negative predictive value of 64% and 97%, respectively (37). Hence, the probability that a patient with normal test results may have a defecatory disorder is very low; however, a careful assessment of the anorectal function should be undertaken for any abnormal results. Most useful to this end is anorectal manometry (32,34-36), which records pressures along the rectum and anal canal both at rest and during spontaneous or induced defecation with an intrarectal balloon, assesses rectal responsiveness, and identifies anorectal reflex indemnity. In dyssynergic patients inadequate relaxation or paradoxical contraction at the anal canal is identified, as well as the presence or absence of enough intrarectal pressure to propel stools. Both the balloon expulsion test and anorectal manometry have, among others, the drawback of their performance with the anal canal permanently occupied by a tube, which is no guarantee that the defecatory maneuver will replicate what the individual experiences in his or her daily life. Therefore, if patient symptoms are not accounted for by the findings of these two tests, or any divergence is identified, a defecography study should be carried out (33,38). Besides function, this technique allows also the study of anorectal anatomy during the voluntary process of defecation. Two techniques are available: videofluoroscopy, which assesses and quantifies the ability to expel rectal contents (with the patient seated on a radio-translucent commode) and the presence of structural abnormalities in the sigma, rectum and anal canal, and magnetic resonance (MR) defecography, which also displays soft perirectal tissues and the genitourinary system in multiple anatomical planes, makes use of no ionizing radiation, and is less operator-dependent than videofluoroscopy. Both techniques must be performed in specialist units, and the interpretation of results should always be checked against patient symptoms before therapy decisions (particularly involving surgery) are made, given the high prevalence of morphological changes (rectocele, enterocele, intussusception) in otherwise normal individuals.

Which functional studies allow to establish a diagnosis of slow transit time constipation, and where should they be carried out?

Three techniques measure total and segmental CTT quantitatively: radiographic study with radiopaque markers (39), colonic scintigraphy after a meal (40) or the ingestion of an indium-marked capsule (111In-DTPA) (41), and the use of a wireless motility capsule (SmartPill®) (42). All these techniques should be carried out and interpreted in specialist units, with the study with radiopaque markers being most commonly ordered because of its wider accessibility. In Spain, a study in a high number of normal subjects provides reference values for radiological tests (39). The SmartPill® system, although costly, has shown a good correlation with radiological studies for the classification of patients with SCT versus NCT, entails no ionizing radiation, and also assesses motor activity throughout the gastrointestinal tract. This is very important when deciding to perform colon resection surgery for a patient with SCT, since motor disorders must be ruled out for the remaining intestine.

9. What is the clinical utility of knowing which is the pathophysiological type of functional constipation?

Early diagnosis of defecatory dysfunction resulting from dyssynergic pelvic floor is very useful in clinical practice because of the condition's prevalence and response to biofeedback (BFB) therapy as opposed to standard therapy (43-46), and because BFB returns slow CTT to normal in a high proportion of patients (43).

In patients without defecatory dysfunction, CTT will allow a less aggressive approach to therapy. Patients with NCT should never be treated with extreme measures, even less so with surgery. Furthermore, patients with SCT and no defecatory dysfunction commonly experience clinical worsening in response to fiber, and usually respond poorly to routine laxatives (including stimulant laxatives). In this subgroup of patients sacral nerve root neuromodulation (47), as well as subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis for highly selected cases, may effectively achieve satisfactory results (48,49).

10. May a patient experience changing symptoms and meet the criteria for both diagnoses (constipation-predominant IBS and functional constipation) at different times in his or her lifetime?

When Rome criteria are used, both diagnostic overlapping (specially with Rome criteria previous to Rome IV) and diagnostic changes within the same individual are very common over time. A highly relevant prospective study in Primary Care (PC) (n: 432 subjects; FC: 231, IBS-C: 201) showed that 89.5% of patients meeting IBS-C criteria also met FC criteria (as defined at the time in 2005), and 43.8% of patients with FC fully met IBS-C criteria; in up to one third of patients a change in diagnosis (FC to IBS-C and IBS-C to FC) was seen during a 12-month follow-up period (50).

11. What diagnostic tests are needed for the diagnosis of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and of functional constipation?

As discussed above, the diagnoses of IBS-C and FC are made using data from the medical records, which must meet the criteria established by expert group consensus (Rome) (2) (Tables I and II), or the AGA in the case of FC (31).

Once the specific criteria for the diagnosis of either condition (IBS-C or FC) have been confirmed, and given the key requirement that symptoms must not have an organic, metabolic or drug-related origin, the diagnostic tests needed to account for symptom functionality should be clearly laid out. Symptom-driven history taking and careful physical examination are mandatory, and should help exclude both intestinal and extraintestinal diseases (Table IV), or the use of symptom-inducing drugs (Table V). They will also reveal whether any alarm symptoms are present (Table VI) that could prompt the ordering of specific diagnostic tests.

In the absence of alarm criteria, which laboratory or imaging tests are key to rule out a metabolic or organic cause for patients meeting the consensus clinical criteria of IBS-C or FC?

Except for a cell blood count (CBC) to assess the presence of anemia and/or infection, tests such as electrolyte, thyroid hormone, and calcium levels, and complete blood chemistry (fasting glucose, urea, creatinine, etc.) neither have proven to have diagnostic usefulness, nor are they cost-effective (31,33,50). Thus, such tests should only be ordered when the parameters they measure are suspected to be abnormal.

The usefulness of plain abdominal X-rays (51,52) or opaque enema (53) to unveil discriminating morphological characteristics with respect to the normal population remains also to be demonstrated, and no evidence supports the usefulness of colonoscopy in patients with clinical constipation (54,55). As a result, consensus guidelines (31,33,38) do not recommend that laboratory or morphological studies be performed, unless risk criteria are met or an organic or metabolic condition is suspected.

Which studies should be ordered when alarm criteria are met?

In addition to specific testing according to the index alarm finding, colonoscopy should be used in most cases.

What sort of laboratory and imaging follow-up should be implemented for patients diagnosed with IBS-C or FC who have remained clinically stable, with no alarm signs or symptoms, for several years?

None. The only exception would be a patient meeting age-related colorectal cancer (CRC) screening criteria or the development of CRC in a family member. In such cases the relevant studies, that is, fecal occult blood (FOB) or colonoscopy, should be performed (33).

What sort of follow-up should a patient with a well-established diagnosis of IBS-C or FC who develops changes in symptom severity, frequency, or response to treatment undergo?

In absence of a plausible explanation for such changes, a search for the presence of some causal condition should be initiated on an individual basis. Following a new physical examination, the time when previous laboratory and morphological tests (if any) were performed should be considered, and changes in the family epidemiological characteristics should be recorded. Typically, both conditions include stages where symptom severity changes and patients perceive they may have an organic disease that remains insufficiently explored. Furthermore, the fact that FC and IBS-C are interchangeable diagnoses over time within one same individual when using Rome criteria should be taken into account; up to one third of patients with FC will meet the IBS-C criteria within on year, and vice versa (4), which should not prompt further diagnostic testing. Only alarm symptoms or signs should warrant additional tests.

Once a patient is diagnosed with IBS-C or FC, which functional studies should be carried out, and when? Are symptoms useful to suspect the pathogenic mechanism underlying FC?

Patients with constipation, with or without IBS criteria, may develop functional anorectal changes or colonic motor disorders that will not respond to routine measures, which makes specific functional testing mandatory (Algorithms 2 and 3). The most common functional anorectal disorder is dyssynergic defecatory dysfunction, which affects from 14.9% to 52.9% of patients with FC (36), and basically results from impaired anal opening at defecation or insufficient rectal propulsion during the expulsive phase. Early diagnosis is very important for this disorder, which requires a specific therapy (anorectal BFB). Data may be found in the medical records that, although nonspecific for the diagnosis of anorectal dyssynergia (56,57), are more common in this condition according to some studies anal pain at defecation (7), manual maneuvers to help in stool expulsion, defecatory straining, and anal blockage (58). Furthermore, there is a sign strongly associated with this disorder when elicited by experienced clinicians, namely the presence of a paradoxical anal contraction when the patient performs a defecatory maneuver during an anorectal digital exam (59,60). In the presence of this sign, as elicited by experts under intimacy conditions, a balloon expulsion test should be ordered; if abnormal, an anorectal manometry procedure should follow to confirm dyssynergia. However, since these requirements (expertise in dynamic digital exams, properly conditioned exploration rooms) are rarely found in daily clinical practice, guidelines suggest that these tests be ordered for any patient unresponsive to management with hygienic-dietary measures, lifestyle changes, and routine laxatives when dyssynergia is suspected from symptoms or an anal digital exam (33,36); more stringently, this should even be a mandatory requirement before ordering such tests for patients also refractory to serotonin agonists and secretagogues (38). For patients with conflictive balloon expulsion test and anorectal manometry findings, a fluoroscopic or MR defecography procedure should be ordered to assess the presence of occult structural changes (enterocele, intussusception, rectocele) and/or to confirm pelvic floor dysfunction during defecation maneuvers.

Some symptoms are more prevalent in patients with SCT FC according to some observational series: defecatory infrequency (58,61), constipation since childhood, and dependence on laxatives (61), but only stool consistency (very hard, Bristol < 3) has been shown to have predictive value for the diagnosis of SCT (sensitivity 85%, specificity 82%) (62). Presently, CTT must be studied in patients not responding to any therapy, preferrably once anorectal dyssynergy has been ruled out using the balloon expulsion test and anorectal manometry (31,33,38).

12. May functional constipation pathophysiological subtypes be diagnosed in the Primary Care setting? How?

According to diagnostic criteria, pathophysiological constipation subtypes require diagnostic techniques not available in the PC setting; however, some basic symptoms or signs have shown fairly good correlation with the results obtained using said techniques. Given the potential significance the prioritization of specific tests may have from a prognostic and therapeutic perspective, awareness and recognition of these symptoms and signs is crucial.

For a diagnostic approach to FC subtypes in PC, careful history taking and physical examination are key. During anamnesis the following should be elicited: defecatory pattern (stool frequency and consistency), associated symptoms and signs (pain, discomfort, distension, defecatory straining, feeling of incomplete evacuation, manual removal of stool, etc.), prior therapy history (lifestyle changes, dietary measures, laxatives, painkillers, antidepressants, etc.), and prior response to treatment. Physical examination must include a complete abdominal exploration, anal and perineal inspection, and dynamic rectal exam (with defecatory maneuver) (63).

As discussed above, symptoms may be elicited that, based on their differential prevalence, suggest dyssynergic defecation or SCT, and most importantly, the afore-mentioned sign, anal dyssynergy during anorectal digital examination, with predictive value (under expert hands) for the diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation.

Treatment

13. The importance of therapy compliance and general practical considerations regarding treatment options

As with any health condition, stringent compliance is essential for the effectiveness of prescribed therapy (Algorithms 4 and 5). In the present case, this includes adherence not only to drugs but also to hygienic-dietary measures (Table VII) and lifestyle changes, when appropriate.

Indeed, prescribing a therapy regime is not enough, as it will be useless unless the patient understands it, accepts it, and agrees to follow it. Therefore, this is not about patients obeying and complying with a prescription, but a trust-based patient-doctor relationship should be set up to promote cooperation, and the patient's active role in decision-making and responsibility regarding self care.

Therefore, in addition to objetively considering the best therapeutic options available, other aspects must be assessed to facilitate patient engagement and compliance. These include the following:

- Use drugs with simple dosage schemes; least possible number of doses or galenic formulations allowing simpler administration.

- Provide patient with simple, easy-to-understand written information and reminders.

- Provide compliance "diaries" to track adherence to medication or prescribed activities.

- Provide patient with information on the condition's pathophysiology according to his or her idiosyncracy and education level to promote involvement in self-care.

- Include family members and caregivers in all these strategies so that they may positively reinforce patient's behavior.

- Regularity is very important for constipation management. While some patients permanently medicate themselves with stimulant laxatives, others only use them intermittently and on an ad hoc basis for exacerbations; other patients avoid all treatments mistakenly believing that laxatives induce dependence or may be ultimately dangerous.

Finally, and importantly, nurses may play a highly effective role in health care education and in monitoring patient outcomes.

At any rate, attempts to assess a therapeutic regime's effectiveness will be useless if optimal patient adherence is not secured. Ineffectiveness will not improve with isolated or overall prescription changes unless patient's engagement can be gained.

14. Usefulness of aerobic exercise to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension

Exercise is often empirically recommended to improve constipation and abdominal distension. Aerobic exercise is useful to maintain adequate bowel function and cut down stress (64).

Efficacy

A regular aerobic exercise schedule (walking, cycling) may be effective against constipation, and improvements in total and recto-sigmoid CTT have been reported (65). Benefits on abdominal distension and gas retention have also been observed (66), but to a lesser extent when compared to healthy subjects (67). Two additional studies reported overall symptom and fecal consistency improvement in IBS (68,69). Other aspects that may play a role in IBS, such as anxiety and depression, were also improved (68).

Limitations

Regular and moderate aerobic exercise according to patient fitness has no significant clinical limitations except in patients with impaired mobility. However, optimal intensity and duration remain to be established.

Practical recommendations

Regular aerobic exercise may help relieve constipation, favors intestinal gas evacuation, and improves distension; exercise recommendation to patients with IBS-C or FC seems thus advisable.

15. Does increased fluid ingestion improve constipation?

Most clinical guidelines recommend lifestyle changes including adequate fluid ingestion and a fiber-rich diet. Specifically, an ingestion of 1.5-2 l of liquids daily is recommended by some guidelines (49,70,71) and by more specific reviews about FC in the elderly (72).

Efficacy and limitations

In one randomized study, the intake of 2 l of water daily by patients with FC already on a fiber-rich diet improved defecatory frequency and reduced laxative needs (73). However, no clinical trials are available to demonstrate that fluid ingestion alone, without any concomitant measures, does improve constipation except for dehydrated patients (49,50).

Practical recommendations

While evidence is insufficient to recommend increased fluid intake, this approach is indeed somewhat beneficial for mild constipation when associated with adequate fiber ingestion in the diet.

16. Usefulness of fiber in the diet to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension

Most guidelines recommend eating a fiber-rich diet to relieve constipation. A gradual increase in fiber is usually advised to prevent abdominal distension; the recommended amount of fiber is at least 25-30 g daily. However, while this measure may improve defecatory frequency and stool consistency, it also may worsen symptoms such as abdominal pain and distension.

Efficacy

A meta-analysis concluded that eating prunes (100 g/day) is beneficial for constipation, the effect reported being superior to that of Psyllium (74).

Another meta-analysis found that fiber-rich diet is useful to improve constipation but not so to relieve abdominal pain and distension in patients with IBS (75). In this same systematic review food-related soluble fiber is what benefitted patients with IBS.

Limitations

Although soluble fiber-rich foods may have some benefits for constipation, the same does not ring true for nonsoluble fiber. A meta-analysis of 5 studies with a total of 221 patients concluded that no differences exist in symptom relief between subjects taking insoluble fiber and subjects on a low-fiber diet or on placebo (relative risk [RR]: 1.02; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.82-1.27) (76). Furthermore, in patients with severe constipation and significantly slowed down CTT, high-fiber diet is ineffective and may worsen pain and distension (49).

Practical recommendations

Dieting on foods with high soluble fiber contents (such as prunes) has proven beneficial against mild constipation but not against abdominal pain and distension; these symptoms may in fact worsen in patients with IBS.

17. Usefulness of diets in constipation-predominant IBS and functional constipation to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension

Approximately two thirds of patients with IBS believe their symptoms are triggered by some specific food.

Wheat sensitivity in the absence of celiac disease has been reported in some patients with IBS. A clinical trial that studied 920 patients with IBS symptoms found that one third of subjects worsened (increased abdominal pain and distension) after receiving wheat but not placebo (77). However, the role of non-celiac gluten sensitivity remains to be established: in a study in patients diagnosed with this condition and who met IBS criteria, randomized, blinded gluten administration at different concentrations could not be told apart from placebo (78).

While lactose malabsorption plays no role in constipation, it has been associated with abdominal pain and distension in patients with IBS. A systematic review analyzed the findings of 7 studies in IBS patients undergoing a lactose intolerance hydrogen breath test; over one third had lactose malabsorption, and lactose intolerance was more common among patients versus control subjects (79). However, patients with IBS often display gastrointestinal symptoms after eating dairy products even if lactose malabsorption cannot be demonstrated.

Furthermore, by extrapolating the intolerance hypothesis to several carbohydrates in IBS, diets free from oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and fermentable polyols (FODMAP) have been proposed. In a randomized study, 41 patients with IBS received low FODMAP diet or their regular diet; 68% of patients on the low FODMAP diet reported adequate symptom control versus 23% of those on their regular diet (p = 0.005). Stool consistency did not change in either group (80). However, in a recent study low FODMAP diet was not superior to traditional dietary counseling for IBS (81).

Limitations

For side effects these diets may potentially induce malnutrition when sustained.

Practical recommendations

The role of some dietary components as symptom triggers or in the pathogenesis of IBS is of increasing interest. Gluten-free diet and low FODMAP diet seem to improve abdominal pain and distension but not constipation in IBS. Low FODMAP diet has not been assessed in patients with FC but its usefulness is unlikely. In short, the current evidence to support their routine use for IBS and FC in clinical practice is limited.

18. Usefulness of fiber supplementation to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Which type of fiber? How is tolerability?

Mechanism of action

Dietary fiber supplements include several complex, poorly digestible carbohydrates that reach the colon unchanged to contribute to fecal bulk; they are partly fermented by the microbiota, which results in short-chain fatty acids, water and gas (hydrogen, methane, carbon dioxide). They are usually classified as soluble and insoluble fiber, according to their behavior in water solutions. The biological effects of fiber include CTT acceleration, increased biomass with colonic pH and microbiota changes, and potential changes in permeability and inflammation (82).

Efficacy

Several meta-analyses have reviewed the evidence on fiber for FC and IBS. All of them agree that drawing joint conclusions is challenging because of the studies' heterogeneous designs, varying goals, and poor quality. Overall, fiber is beneficial for constipation symptoms (stool numbers, defecatory straining) or secondary endpoints (use of laxatives); it is superior to placebo, especially soluble fiber (Psyllium), in the studies with both FC and IBS patients. The effects on other symptoms such as pain and distension remain unclear (83-85).

Adverse effects

The main adverse effects of dietary fiber derive from its potential to induce distension, usually as a result of gas from bacterial fermentation. Most clinical trials do not report this as relevant, but clinical practice shows this effect may be significant, particularly for patients with constipation associated with abdominal pain and distension (86).

Limitations

The use of dietary fiber supplements has no signifcant clinical limitations; they should be used with caution and clinical monitoring in bedridden patients or in individuals with severely disordered intestinal and colonic motility because of increased impaction risk.

Practical recommendations

The use of dietary or supplemental fiber is a rational first-line therapy for any patient with constipation, whether associated with abdominal discomfort or otherwise. Evidence is stronger regarding soluble fiber, and a therapy trial of 6 weeks usually suffices to assess efficacy (87). Attention must be paid not only to efficacy but also to tolerability, hence gradual increases in fiber amount are to be advised.

19. Usefulness of osmotic laxatives to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

Osmotic laxatives contain non-absorbable ions or molecules that retain water in the bowel lumen. Polyethylene glycol (PEG), lactulose, and magnesium salts are most commonly used.

Efficacy

These laxatives improve constipation and fecal consistency, but abdominal pain and distension respond poorly. According to available studies, PEG is most supported by evidence, but magnesium salts are commonly used in clinical practice with satisfactory results.

Only two clinical trials have studied the use of osmotic laxatives (PEG) for IBS-C. The first one found no superiority over placebo (88). The second trial found benefits in terms of defecatory frequency but not of abdominal pain and distension (89).

As regards specific FC studies, 5 trials evaluated PEG versus placebo. PEG superiority was demonstrated with a NNT (number needed to treat) value of 3 (95% CI: 2-4). Lactulose was also superior to placebo with a NNT of 4 (95% CI: 2-7) (90).

In another systematic review comparing PEG and lactulose, PEG was superior in terms of number of weekly stools, fecal consistency, abdominal pain relief, and need for other drugs (91).

Adverse effects

Most common side effects include abdominal pain and distension, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Hypersensitivity reactions (rash, urticaria or edema) have been reported in a few patients only. They have a good safety profile and may be used by the elderly, during pregnancy, and during breastfeeding. They can also be used in patients with liver or kidney failure. PEG has fewer side effects as compared to lactulose, and may be safely dosed for prolonged periods of time (up to 6 months). Regarding magnesium salts, the most commonly reported adverse effect is electrolyte imbalance; hence they must be used cautiously in patients with impaired renal function at risk for hypermagnesemia (71).

Limitations

The primary limitation of this type of laxatives is their poor relief of abdominal pain and distension, symptoms that are significant particularly for patients with IBS. PEG seems to be somewhat superior to lactulose in this respect, hence the latter is not advisable for patients with IBS-C (92).

Practical recommendations

Osmotic laxatives are useful to treat constipation but not so to manage abdominal pain and distension; therefore, they are first-line agents for FC but their usefulness is more limited in IBS-C. PEG is more effective than lactulose for symptom control, and also has fewer side effects, hence it is to be considered to be first-choice. These laxatives have a favorable safety profile and may be used in specific situations such as in the elderly, during pregnancy, and in patients with impaired liver and/or kidney function.

20. Usefulness of stimulant laxatives to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

These drugs promote water and electrolyte secretion in the colon or induce colonic persitalsis. They include diphenylmethanes (phenolphthalein, bisacodyl, sodium picosulfate) and anthraquinones (Senna, bearberry, Aloe vera).

Efficacy

Two clinical trials studied the efficacy of bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate. The first one included 247 patients who received 10 mg of bisacodyl versus 121 who received placebo once daily for 4 weeks. Bisacodyl was superior to placebo to improve constipation and its related symptoms, as well as quality of life (93). The second trial assessed the effectiveness of sodium picosulfate versus placebo; 131 patients received 10 mg of sodium picosulfate and 71 received placebo for 4 weeks. As above, sodium picosulfate was superior to placebo to improve constipation (94). Considering both studies combined, 42.1% of patients in the laxative group failed to respond to therapy, versus 78% of those receiving placebo; NNT was 3 (95% CI: 2-3.5) (90).

Adverse effects

Most common adverse effects include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. Allergic reactions have been described less often. Prolonged regimens may induce loss of fluids and electrolytes, hence they must be used cautiously in the elderly, in patients with heart failure, and in patients on diuretics or corticosteroids. Insufficient studies are available to support safety during pregnancy, therefore they cannot be recommended to pregnant women.

Limitations

As with osmotic laxatives, these drugs have not proven effective for abdominal pain and distension relief, and may even worsen these symptoms. Furthermore, they fail to induce a "predictable" bowel rhythm in many patients.

Practical recommendations

Stimulant laxatives are useful in the treatment of constipation, but no so good for abdominal pain and distension; therefore, their utility is limited in IBS-C. Their safety profile falls below that of osmotic laxatives.

21. Usefulness of probiotics to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension

Mechanism of action

Probiotics are live bacteria that possess characteristics such as survival in the gastrointestinal tract, adherence to the intestinal epithelium, and intestinal flora modulation. They inhibit potentially pathogenic bacteria, and have various immunomodulating and immunostimulating effects; they promote immune cell proliferation, enhance phagocyte activity, and increase IgA production. All this determines their potential benefits in preventing infection, particularly by intestinal pathogens, as well as bacterial translocation (95-97).

Efficacy

According to the relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the usefulness of probiotics to relieve overall symptoms (defecation, bloating, pain improvement) in patients with IBS remains unclear, with studies that find positive results and studies that find no significant differences.

Regarding FC, evidence is even poorer, given the heterogeneity and biases found in the relevant studies (90,98-100).

Adverse effects

No study has ever found side effects with the use of probiotics in these patients.

Limitations

No limitations to the use of probiotics are found in any study.

Practical recommendations

Given the current lack of evidence to support their use because of conflicting results regarding their effectiveness to relieve abdominal pain and distension, and to improve bowel movements in patients with IBS-C and FC, as of today we cannot recommend their use in these patients.

22. Usefulness of antibiotics to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension

Mechanism of action

Rifaximin is a synthetic antibiotic derived from rifamycin and active against Gram-positive and Gram-negative germs, as well as both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria; it is not absorbed by the intestinal mucosa (< 0.01% following an oral dose), hence it has intraluminal activity and no systemic effects. It prevents pathogens from adhering to the bowel mucosa and from invading epithelial cells by binding microbial RNA-polymerase subunit β, thus inhibiting transcription and the synthesis of ribonucleis acid (RNA) (101).

Efficacy

Rifaximin seems to reduce distension, flatulence and abdominal pain in patients with IBS without constipation, according to the relevant studies (90,101-103). One study suggests its potential role for patients with IBS-C (104).

No studies have assessed rifamixin effects on FC.

Limitations. Adverse effects and contraindications

Studies and reviews do not report major side effects or adverse events seen more frequently than with placebo (3-5).

Practical recommendations

Evidence is currently insufficient to support recommendations regarding the use of rifaximin in patients with FC or IBS-C; however, the drug may reduce bloating and flatulence.

23. Usefulness of spasmolytics to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

Spasmolytics have been traditionally used for the empiric management of IBS based on the fact that colonic smooth muscle contraction contributes to IBS manifestations, particularly pain. They include 3 major types: calcium channel blockers (otilonium and pinaverium), direct smooth muscle relaxants (mebeverine), and antimuscarinic/anticholinergic agents (hyoscine, cimetropium, dicyclomine hydrochloride).

Efficacy

Spasmolytics are superior to placebo for improving IBS symptoms, especially abdominal pain and distension (38% in the placebo group and 56% in the antispasmodic group; OR: 2.13 [95% CI: 1.77-2.58]) (105). The effect of individual spasmolytics is variable and difficult to interpret, as only a reduced number of studies have assessed each of the 12 drugs available. Among them, otilonium bromide (5 trials) and hyoscine (3 trials) had evidence of efficacy (76). Cimetropium bromide, pinaverium bromide, and dicyclomine hydrochloride have also demonstrated benefits to some extent (90). However, study heterogeneity is to be considered. Other assessed spasmolytics did not better than placebo.

Another multicenter clinical trial also revealed that patients receiving otilonium bromide were less likely to present with symptom recurrence versus placebo (106).

Adverse effects

Fourteen per cent of patients treated with antispasmodics reported side effects versus 9% of those receiving placebo. Most commonly reported side effects included dry mouth, dizziness, and blurred vision, with no serious adverse event reported. The relative risk of having an adverse effect versus placebo was 1.61 (95% CI: 1.08-2.39) (76,90).

Spasmolytics with greater anticholinergic activity may induce visual changes, urine retention, constipation, and dry mouth. They must be dosed with caution in elderly patients with a history of acute myocardial infarction and hypertension. Their use during pregnancy and breastfeeding is not recommended, as their safety remains to be established in such situations.

Limitations

Spasmolytics are useful to relieve pain and distension, but have no effect on constipation.

Practical recommendations

Spasmolytics are effective against abdominal pain and distension in patients with IBS, with a favorable safety profile. Side effects are uncommon. However, those with greater anticholinergic effects may induce adverse events at high doses.

24. Usefulness of peppermint essence to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension

Mechanism of action

Peppermint essence, also commonly denominated peppermint oil, has spasmolytic properties and may modulate pain by attenuating visceral hypersensitivity.

Efficacy

Two systematic reviews show an effect superior to placebo's in the management of pain in patients with IBS (76,90). The most recent review included 5 trials for a total of 482 patients (107-111); it showed a statistically significant positive effect of peppermint oil versus placebo, with a NNT of 3 (95% CI: 2-4) (90). However, there was significant heterogeneity among studies.

Adverse effects

The above-mentioned studies reported no significant side effects versus placebo. Peppermint essence usually has no adverse effects at standard doses, but allergic reactions, heartburn, and headache have been described. The safety profile during pregnancy and breastfeeding is unknown at the standard doses given for IBS, so it cannot be recommended in such situations.

Limitations

As with other antispasmodic agents, this compound has not demonstrated effect on constipation.

Practical recommendations

Peppermint essence has proven effective for the management of pain and distension in patients with IBS with few adverse effects.

25. Usefulness of prucalopride to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

Serotonin (5-HT) plays a key role in the gastrointestinal tract, where it affects the secretory, motor, and sensorial functions. Seven 5-HT receptor subtypes may be found in the gut. Of these, receptor 5-HT4 favors intestinal secretion, and enhances peristalsis and bowel transit (112). Prucalopride is a highly-selective 5-HT4 agonist that stimulates intestinal motility (113).

Efficacy

In phase-3 trials prucalopride was superior to placebo for improving constipation, abdominal pain and abdominal distension, as well as quality of life (114-116).

In a systematic review of 8 clinical trials, the response to prucalopride for constipation improvement was superior to the response elicited with placebo (therapy failed in 71% of patients with prucalopride and in 87.4% with placebo), but significant heterogeneity was identified amongst studies (90).

A meta-analysis including 9 trials also showed prucalopride to be effective for constipation with at least 3 bowel movements weekly (RR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.07-2.49). It also improved quality of life (RR: 1.51; 95% CI: 1.07-2.11) and stool consistency (mean difference versus the control group 9.16; 95% CI: 7.28-11.03) (117). It seems to be as well a useful drug against refractory constipation in the elderly, according to the results obtained in a phase-2 clinical trial (118).

Furthermore, its potential role in other motility disorders that manifest with constipation, including chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, must be highlighted, even though evidence is now scarce. Prucalopride improved abdominal pain and distension in patients with this condition (119).

Further studies are needed to assess the combination of prucalopride with other drugs, such as linaclotide or lubiprostone, in patients with severe constipation.

Adverse effects

The drug is safe and well tolerated. Most common side effects include headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. It has an excellent cardiac safety profile because of its selective affinity for intestinal 5-HT4 receptors. However, it must be used with caution in patients with advanced renal failure or seriously impaired liver function. Prucalopride is not recommended during pregnancy (category C drug) or breastfeeding.

Limitations

The drug is not commercially available in Spain with the indication of IBS-C. However, from all the above, it may play a role in patients with severe IBS-C failing to respond to other therapies.

Practical recommendations

Prucalopride is effective in the treatment of FC unresponsive to other drugs; to a lesser extent, it also improves pain and distension in these patients with a good safety profile. It may be used in the elderly with refractory constipation, where the use of half doses (1 mg) is advisable.

26. Usefulness of linaclotide to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

Linaclotide is a guanylate cyclase C agonist that increases intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels in the enterocyte. Intracellularly, cGMP increases bicarbonate and chloride secretion unto the bowel lumen, and diffuses to the extracellular compartment to inhibit sensory nerve terminal activity. From a pharmacodynamic standpoint, its ultimate effect is increased intraluminal secretion leading to enhanced transit and a visceral analgesic action, with reduced sensory thresholds to mechanical distension (120,121).

Efficacy

Based on the clinical trials and meta-analyses that compared linaclotide to placebo (122,123) both in patients with IBS-C (RR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.3-2.9, based on 7 studies) and in patients with FC (RR: 4.26; 95% CI: 2.80-6.47, based on 3 studies), linaclotide is clearly effective for relieving constipation symptoms with a NNT of 7 (95% CI: 5-11) (122) in both groups, with highly homogeneous results across studies. Linaclotide effects not only target constipation but also improve pain and distension in both groups (FC, IBS-C) as seen in clinical trials (benefit of 15-30% over placebo).

Adverse effects

From a practical perspective, the only relevant adverse effect reported was diarrhea, the significance of which should be assessed with the patient. In fact, clinical trials report diarrhea in about 20% of patients on linaclotide, but only 2% of cases are considered as severe. Diarrhea led to drug discontinuation in 4.5% of patients.

Limitations

Linaclotide is not absorbed and does not enter systemic circulation, nor does it affect cytochrome P450. Therefore, while it has not been studied specifically in patients with liver or kidney failure, its use in these patients has no foreseeable limitations. Efficacy and safety are similar in the elderly and in middle-aged adults. Although unlikely, no evidence of teratogenicity exists, hence the drug cannot be recommended during pregnancy. The drug is available in Spain for the treatment of IBS-C, not for FC. It is indicated for FC in other European countries and the USA in half doses.

Practical recommendations

Linaclotide is the drug of choice for patients with constipation and abdominal complaints such as pain and distension when dietary fiber and laxatives have failed (122,123).

27. Usefulness of lubiprostone to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

Lubiprostone is a prostaglandin derivative that activates type-2 chloride channels (ClC-2) at the enterocyte's luminal membrane, which increases chloride secretion to the bowel lumen thus enhancing bowel transit. No effects on visceral sensitivity have been described.

Efficacy

Lubiprostone has proven effective to improve constipation symptoms with a NNT of 4 (95% CI: 3-7) (124). Clinical trials in patients with IBS have shown some effects on pain (approximately 7% benefit over placebo) that develop after one month on therapy (124,125).

Adverse effects

Major adverse effects include diarrhea and nausea, the latter occurring in up to 15% of patients in the active group. Although rarely, dyspnea has been described in association with lubiprostone.

Lubiprostone requires no dosage adjustment in patients with kidney failure; while no evidence of liver metabolism exists, the FDA recommends that doses be reduced for patients with Child-Pugh B or C liver disease. Its use is contraindicated during pregnancy, this being a class C drug.

Practical recommendations

Lubiprostone is not available in Europe.

28. Usefulness of anorectal biofeedback to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension

Mechanism of action

Anorectal BFB is a retraining technique indicated for patients with dyssynergic defecation. The physiological activity of the anus and rectum is monitored, and the results are shown to the patient, who is trained on the appropriate maneuvers to correct undesired patterns.

Efficacy

Studies comparing BFB to sham BFB, standard management, laxatives or diazepam (44,126) found that BFB is superior, to variable extents, to all these comparators in improving constipation symptoms. Only one study assessed its effects on abdominal pain, and found significant benefits over laxatives. No study has ever assessed the effects of BFB on abdominal distension.

Adverse effects

None has been described. No limitations exist beforehand for BFB according to patient characteristics, but appropriate willingness and the ability to follow instructions and complete retraining are key factors for success.

Practical recommendation

BFB is the technique of choice for patients with constipation and established pelvic dyssynergia (127).

29. Usefulness of antidepressants to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

The pathways through which these drugs exert their beneficial effects vary according to their class.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (amitriptyline): They modulate pain perception at the central nervous system (128).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (fluoxetine, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram): They decrease visceral sensitivity, improve the sense of well-being, possess anxiolytic properties, and potentiate the effects of other medications, including TCAs (128,129).

Serotonin, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine): They block both serotonin and norepinephrine receptors, thus improving pain control (130).

Efficacy

Regarding the efficacy of TCAs and SSRIs, findings vary according to each individual drug. In a meta-analysis (128), the use of TCAs or SSRIs generally improved distension, pain, and stool consistency in patients with IBS, with a NNT of 4 for both medications (95% CI: 3-6; 4 for TCAs with a 95% CI of 3-8, and 3.5 for SSRIs with a 95% CI of 2-14). However, TCAs should not be used against IBS-C because of their increased constipation effect.

Furthermore, a study (129) of fluoxetine (SSRI) for 16 weeks concluded that this drug, in doses lower than those used for psychiatric disorders, improved all IBS-C symptoms (pain, distension, stool consistency). A randomized, double-blind analysis of paroxetine versus placebo found no significant differences in the primary endpoint (abdominal pain), but did find differences in overall memory and symptom severity (131). Studies supporting citalopram are also available (130).

As regards SNRIs, only duloxetine 60 mg/day has been studied in patients with IBS (132), and proven effective for abdominal pain and stool consistency.

Limitations. Adverse effects (133)

TCAs: They have the greatest number of side effects because of their multiple mechanisms of action (dry mouth, constipation, nausea, vomiting, orthostatic hypotension, etc.). As they markedly enhance constipation, their use in IBS-C (and obviously FC) is advised against. Caution must be exerted in patients with heart conditions, with neurological or urological disorders, and with liver dysfunction, among others.

SSRIs: They are better tolerated than TCAs. Side effects are usually mild but disturbing, and lead to drug discontinuation occasionally. Adverse events include dry mouth, somnolence, reduced libido, anorgasmy, gastrointestinal changes (nausea, diarrhea or constipation), and weight increase.

SNRIs: They are also better tolerated than TCAs. They may induce nausea, somnolence, dizziness, diarrhea, fatigue, constipation, hyperhydrosis, dry mouth, vomiting, decreased appetite, asthenia, and anorexia.

Practical recommendations

The use of antidepressants in doses lower than needed for psychiatric disorders may be indicated for the treatment of persistent distension and pain, and to improve stool consistency in IBS-C. SSRIs are recommended for IBS-C, whereas TCAs should be avoided. Their use should be reserved for patients with persistent symptoms following other therapies (hygienic-dietary measures, laxatives, linaclotide), and for those with an associated psychiatric disorder for which their use has been indicated. When clinically effective, it is advisable that treatment be prolonged for at least 6 months.

Currently, data are insufficient to recommend these drugs in patients with FC, except when indicated to treat psychiatric comorbidity.

30. Usefulness of psychological therapies in patients with IBS to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

Several studies have pointed out the association between psychological stress and the worsening of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS (134-137). These therapies play no role in the management of FC. Psychological therapies may reduce stress, modify the visceral perception threshold, and consequently improve the clinical picture of patients (64) in terms of pain and bowel habit.

Efficacy

A systematic review of psychological therapies including 2,189 patients found a statistically significant effect of these therapies with a NNT of 4 (95% CI: 3-5); however, heterogeneity was significant and quality was poor among the studies involved (90). Furthermore, double-blind studies could not be selected because of the type of treatment. Regarding the 10 types of therapy involved, cognitive-behavioral therapy, hypnotherapy, face-to-face and over-the-telephone multicomponent therapy, and dynamic psychotherapy had proven useful (90).

Hypnosis may modify the visceral perception threshold and provide short-term and long-term clinical improvement (138,139).

Side effects

None has been described.

Limitations

These types of therapy require patient cooperation, as well as time and commitment from both patient and therapist alike. In addition, these therapies are expensive and difficult to be accessed.

Practical recommendations

Some psychological therapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and hypnosis, may be useful to manage abdominal pain and reduce stress in patients with IBS.

31. Usefulness of acupuncture in patients with IBS to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects

Mechanism of action

Acupuncture relies on the stimulation of so-called acupuncture or "trigger" points, which are found throughout the body and related to organs and other body components (joints, musculoskeletal bundles, etc.), through the insertion of thin needles into the skin. A number of acupuncture points are related to abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation, and may act upon these symptoms when properly stimulated (140).

Efficacy

A meta-analysis including 17 controlled, randomized studies to assess the potential benefits of this technique to improve symptoms and quality of life in patients with IBS found no positive evidence in this regard (141).

Another study that assessed acupuncture having overall symptom improvement as primary endpoint, and the improvement of quality of life and individual symptoms as secondary endpoints, also found no evidence for acupuncture (142).

As of today, no studies have assessed the effects of acupuncture on FC.

Limitations

None have been described.

Practical recommendations

No evidence supports recommending acupuncture to improve symptoms or quality of life in patients with IBS-C or FC.

32. Usefulness of suppositories and enemas as salvage therapy to improve constipation. Adverse effects and special precautions

Enemas and suppositories are essential for the treatment of constipation complicated with fecal impaction, as well as of some cases of obstructive defecation, and to supplement other therapies for severe constipation with significantly impaired bowel transit for the cleansing of the distal colon.

Mechanism of action

Different types of enemas and suppositories are available. All induce rectal distension, thus favoring defecation. Depending on type, enemas may have additional mechanisms of action; for instance, saline enemas drain water towards the colon, whereas phosphate enemas stimulate colonic motility, and mineral oil or emollient enemas lubricate and soften hard feces. Depending also on type, suppositories have different mechanisms of action. Stimulant suppositories containing bisacodyl are available. Glycerin suppositories act locally. The mechanical stimulus of suppository insertion may in itself trigger defecation.

Efficacy

Scientific evidence regarding which type should be used is scarce, but most commonly used enemas include lukewarm water, saline solution (fisioenema) or some sort of osmotic compound (143).

Anal irrigation with Peristeen®, during which some 750 mL of lukewarm water are introduced in the colon, has been successful for patients with neurogenic bowel dysfunction secondary to spinal injury. The number of procedures needed to attain bowel cleansing was reduced, and patient incontinence and quality of life were improved in a randomized trial versus conservative therapy (144). These encouraging results have been subsequently confirmed by an Italian multicenter study, which concluded it may be considered as the treatment of choice for this type of patients (145). Furthermore, this therapy is cost-effective when compared to conservative management (145,146).

Other commonly used enemas include 250 mL sodium phosphate enemas, which exert osmotic effects, and saline solution enemas (fisioenema), which have no side effects and may be acquired over the counter (phosphate enemas are prescription drugs; their side effects are listed in the section below).

As regards suppositories, some act topically to favor rectal ampulla emptying, and some have active ingredients, including bisacodyl, that are dealt with in the section on stimulant laxatives.

Side effects

No significant side effects have been reported for water irrigation using the Peristeen® system.

Regarding phosphate enemas, prolonged use may result in electrolyte imbalance, including hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and hypernatremia. Therefore, they must be used with caution in patients with a history of electrolyte imbalance including severe renal impairment, in the elderly, in patients with uncontrolled high blood pressure, and in patients with heart failure. Enema abuse may also result in anorectal fibrosis and stenosis from repeat microtrauma (147).

Most commonly reported adverse effects with suppositories include irritation, and anal burning or itching. Given the type of medication involved and its administration route, suppositories have no impact on the concomitant use of other drugs.

Limitations

In some patients, appropriate suppository or enema usage may be challenging (e.g., in patients with motility impairment from spinal injury). However, this difficulty seems smaller with the Peristeen® system.

Practical recommendations

Enemas are useful for constipation complicated with fecal impaction, and as salvage therapy in association with other treatments for severe constipation, although supporting evidence is absent. There is evidence, however, supporting the usefulness of transanal water irrigation using the Peristeen® system in patients with spinal injury, and the system will be likely effective in other severe constipation scenarios.

33. Usefulness of sacral nerve root neurostimulation to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

Stimulation of sacral nerves S3-S4 using electrodes that are initially temporarily implanted for about 4 weeks, and then permanently if proven effective. The mechanism of action remains unclear, but the technique seemingly improves rectal sensitivity and colonic contractility, thus improving CTT.

Efficacy

Studies reporting on the efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation focus on patients with slow transit constipation refractory to all treatments, and no controlled studies are available; efficacy is assessed using cross-over designs. A 2007 Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews meta-analysis found an increase from 2 to 5 in weekly stools, and improved abdominal pain and distension (47). Most relevant is a European multicenter study in 62 patients: the device was permanently implanted in 73% of patients, with sustained constipation, pain, and distension improvement at 28 months of follow-up. However, longer-term benefits remain a concern (148).

Adverse effects

The procedure is not exempt of adverse effects. The multicenter study (148) reported 11 treatment-related serious adverse events; infection, post-implantation pain, mechanical tissue erosion, and electrode migration stand out.

Special precautions include the recommendation to hold back stimulation during prenancy. No safety information is available regarding patients with significant comorbidities.

Practical recommendation

The usefulness of sacral nerve stimulation is controversial, hence should only be considered for patients with intractable SCT FC where dyssynergic defecation has been excluded.

34. Usefulness of surgery to improve: a) constipation; b) abdominal pain; and c) distension. Adverse effects and special precautions

Mechanism of action

Surgery has been suggested for the treatment of severe SCT constipation using resective (colectomy) techniques; the mechanism of action would imply reduced fecal water reabsorption.

Efficacy

No controlled studies of surgery for FC are available, and efficacy must be extrapolated from case report series reviews (48). In this 2011 analysis including 48 studies with 1,443 patients, defecatory frequency improved in 65%, and 88% required no laxatives afterwards. Effectiveness regarding abdominal distension and pain remains unknown.

Adverse effects

According to a case report series review (48), mortality is approximately 0.2%. In addition to immediate complications (ileus: 0-16%, infection: 0-13%, anastomosis dehiscence: 0-22%), other significant delayed complications must be considered (obstruction: 0-74%, incontinence: 0-53%).

Practical recommendation

Surgery should be restricted to exceptional constipation cases with confirmed SCT after excluding intestinal pseudo-obstruction and dyssynergic defecation, and after performing an adequate psychological assessment.

Coordination between levels of care

35. When should a patient with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome or functional constipation be referred to a specialist? Diagnosis and coordination between levels of care

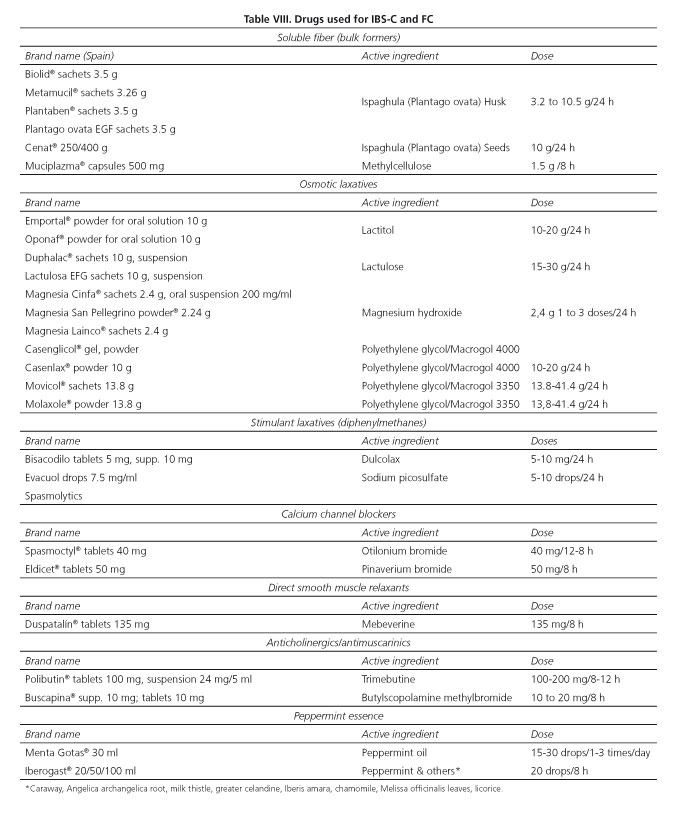

The diagnosis of IBS-C and of FC is well established by the criteria put forward by the Rome's expert panel (Algorithms 1-3, Tables I and II). However, PC clinicians must always be aware of those situations where referral to specialist care should be considered in order to exclude organicity and, on occasion, to optimize the follow-up and treatment of these patients within the frame of integrated, shared care (Algorithms 4 and 5, Tables VIII and IX). Apropriate history taking (including both personal and family history, as well as alarm symptoms and signs) and an attentive physical examination are key factors to reach this end.

Various consensus documents and CPGs establish the reasons that must prompt the ruling out of organic disease, even though accuracy is controversial for some of them (Table VI).