My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.108 n.7 Madrid Jul. 2016

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2016.4521/2016

EDITORIAL

If you suffer from type-2 diabetes mellitus, your ERCP is likely to have a better outcome

Jesús García-Cano

Department of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Virgen de la Luz. Cuenca, Spain

Biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy (BES) was first performed in 1973, almost at the same time, in Germany and Japan (1,2). It was initially intended to remove common bile duct stones (CBDS) or choledocholithiasis in patients who had previously undergone cholecystectomy. In this way, a new surgery was no longer needed in a majority of such patients.

Since 1973 the procedure has expanded over the years and is now a widespread tehcnique in biliary endoscopy. A PubMed search in July 2016 of the MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) term "Sphincterotomy, Endoscopic" yealded 2,929 articles. BES is defined as an incision of Oddi's sphincter or Vater's ampulla performed by inserting a sphincterotome through an endoscope (duodenoscope) often following retrograde cholangiography. Endoscopic treatment by sphincterotomy is the preferred method of treatment for patients with retained or recurrent bile duct stones post-cholecystectomy, and for poor-surgical-risk patients who have the gallbladder still present. Furthermore, BES is commonly performed prior to stent insertion (plastic or metal). BES is a part of the procedure called endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), which has, in turn, 14,025 articles in PubMed.

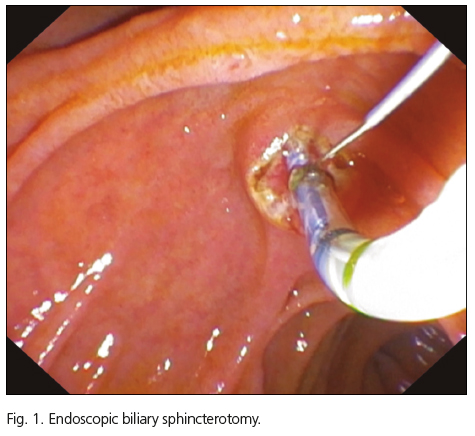

The technique for Oddi's sphincter incision has not basically changed since 1973. It is performed with pull-type or Erlangen-type sphincterotomes. The latter denomination refers to the first German city where the procedure was first used. Tension is given to the device wire, electric current is applied (nowadays a blended current consisting of cut and coagulation) and the papilla of Vater is opened in a stepwise manner (Fig. 1).

The terms papillotomy (from Vater's papilla) and sphincterotomy (from Oddi's sphincter within the Vater's papilla) are synonimous.

Pancreatic endoscopic sphincterotomy (PES) can be also performed cutting Oddi's sphincter from the pancreatic side. It is done to treat main pancreatic duct conditions or, more commonly in recent times, to reach the CBD in the so-called pancreatic techniques for CBD cannulation (3).

After 43 years of BES use worldwide, the four most frequently found complications include post-ERCP acute pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation, and cholangitis. Nevertheless, infection is not directly related to BES, but to failed biliary drainage after contrast injection during ERCP. In the same way, post-ERCP acute pancreatitis is not only related to potential thermal injury because of the electrical current applied during BES, but also to previous cannulation attempts.

The crucial point during ERCP procedures is the deep cannulation of either the CBD or pancreatic duct, or both. The vast majority of ERCPs aim at CBD drainage. Cannulation skills are so important that they constitute a surrogate for total ERCP competency performance (4). In fact, once deep CBD cannulation has been achived, other techniques such as BES or stent insertion are straigthforward. Cannulation technique is believed to be a pivotal factor in the genesis of post-ERCP pancreatitis, and is obviously important for successful cannulation.

The two major persistent problems of ERCP over time are failure of successful biliary cannulation and post-ERCP pancreatitis (5).

After 43 years of BES life span, we may be led to think all has been said about BES outocomes, risks, and complication prevention. For instance, we learned that ERCP is more dangerous in people who do not need it (6), that fewer doctors should perform more ERCPs in order to mantain skills (7), that aged people can be safely treated by ERCP (8), that the whole team of physicians, nurses and other assitants must have good training since a weak link can determine a bad outcome (9). And in summary, non dilated ducts, absence of obstructive jaundice, women under 60 years of age, and treating sphincter of Oddi dysfunction lead to frequent and sometimes severe complications (10).

But very litle was known about the better outcomes of ERCP in patients suffering from type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), as de Miguel-Yanes et al. point out in this month's issue of Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas (Spanish Journal of Gastroenterology) (11).

Scarce references may be found that show links between ERCP and diabetes. In the last few years Uchino et al. (12) reported that patients with diabetes had more frequently painless post-ERCP acute pancreatitis, and Hu et al. (13) found similar complication rates after ERCP regardless of diabetes status.

De Miguel-Yanes et al. (11) used disease- and procedure-related criteria according to the International Classification Diseases-Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM codes), which is used in the Spanish Minimum Basic Data Set managed by the Ministry of Health. The authors compared 23,002 BES procedures in patients with T2DM against 103,883 procedures in patients without T2DM. In this huge database they searched for code 51.85 "endoscopic sphincterotomy and papillotomy", code 51.84 "endoscopic dilation of ampulla and biliary tract", and code 51.87 "endoscopic insertion of stent (tube) into bile duct". They did not look for ERCP (code 51.10, 51.11 and 52.13) to discard non-therapeutic ERCP.

With appropriate ICD9-CM codes they excluded type-1 diabetes mellitus, gallbladder o pancreatic cancer, and people younger than 18 years old. Obese people was also identified.

They looked also for codes related to BES complications such as cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, peforation, and bleeding.

T2DM was found to be associated with lower in-hospital mortality after BES. Time trend multivariate analyses during years 2003 to 2013 showed a significant reduction for in-hospital mortality after BES only in patients who had T2DM.

Obesity was more frequently coded in the T2DM population. The better outcomes associated with obesity have been described in the so-called "obesity paradox" in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (14). Earlier I tried to show that ERCP success depends mainly on single-operator volume of procedures and skills, rather than total number of ERCPs performed in a hospital (15). Similar results were found by other colleagues (16). Something similar to ERCP had been reported for cardiovascular procedures. What matters most is how many procedures are performed by each doctor (17,18). Again, cardiological and endoscopic procedures have in common the fact that moderate obesity is perhaps related to better outcomes.

De Miguel-Yanes et al's. work (11) is based on the ICD-9-CM codes asigned to each certificate of discharge. In Spain, codes asignement is usually done by trained staff rather than gastroenterologists, so they ignore some aspects and techniques related to ERCP. Therefore, perhaps many procedures were coded exclusively as ERCP without any reference to therapeutic details, like BES. Spanish endoscopists are not as familiar with coding procedures as they should be. Thus, complexity and case mix can be properly displayed.

Adequate ICD-9-CM coding for ERCP may include other tecniques such as 52.92 "cannulation of the pancreatic duct", 87.66 "contrast pancreatogram", or 51.82 "pancreatic sphincterotomy".

There are some issues in the paper by de Miguel-Yanes et al. (11) that need explanation. In-hospital mortality was found to be lower for T2DM patients, with further reductions reported over time, whereas, for instance, post-ERCP acute pancreatitis rate is higher in this subset than for patients without T2DM. It is not surprising that older age, comorbidity, and BES performed in an emergency setting had the highest in-hospital mortality rate. A more in-depth analisys could have been done to show how T2DM patients falling in these three risk categories (older, comorbidity, urgent ERCP) were protected by their diabetes. It remains open the question of which mechanisms in type-2 diabetes mellitus serve as protective agents. In addition, as the authors stated, more studies are needed to confirm that these results are present in real clinical scenarios and not as merely statistics.

Despite some criticisms, the work by de Miguel-Yanes et al. (11) is of great scientific value. It is, to my knowledge, the largest Spanish ERCP series, comprising 126,885 BES from 2003 to 2013. It emphasizes the fact that large-scale nation-wide studies can be done.

This article shows that the data collected by the Spanish National Hospital Database (MBDS, Minimum Basic Data Set) managed by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality, compiling data from all public and private hospitals, covering the vast majority of hospital discharges, is a valuable tool for high-quality scientific studies.

References

1. Classen M, Demling L. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla of vater and extraction of stones from the choledochal duct. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1974;99:496-7. [ Links ]

2. Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc 1974;20:148-51. [ Links ]

3. García-Cano J, Taberna-Arana L. A prospective assessment of pancreatic techniques used to achieve common bile duct cannulation in ERCP. Digestive Disease Week. San Diego (California) 19-22 may 2012. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:(4S) AB389 (abstract). [ Links ]

4. García-Cano J. 200 supervised procedures: the minimum threshold number for competency in performing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc 2007;21:1254-5. [ Links ]

5. Bourke MJ, Costamagna G, Freeman ML. Biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: core technique and recent innovationations. Endoscopy 2009;41:612-7. [ Links ]

6. Cotton PB. ERCP is most dangerous for people who need it least. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:535-6. [ Links ]

7. Huibregtese K. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy and their prevention (editorial). N Engl J Med 1996;335:961-3. [ Links ]

8. García-Cano J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients 90 years of age and older: increasing experience on its effectiveness and safety. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;37:348-9. [ Links ]

9. García-Cano J. ERCP outcomes in medium-volume centers. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:356-7. [ Links ]

10. Freeman ML, Disario JA, Nelson DB, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:425-34. [ Links ]

11. de Miguel-Yanes J, Méndez-Bailón M, Jiménez-García R, et al. Tendencies and outcomes in endoscopic biliary sphincterotomies among people with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus in Spain, 2003-2013. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2016;386-93. [ Links ]

12. Uchino R, Sasahira N, Isayama H, et al. Detection of painless pancreatitis by computed tomography in patients with post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography hyperamylasemia. Pancreatology 2014;14:17-20. [ Links ]

13. Hu KC, Chang WH, Chu CH, et al. Findings and risk factors of early mortality of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in different cohorts of elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1839-43. [ Links ]

14. Gruberg L, Weissman NJ, Waksman RF, et al. The impact of obesity on the short-term and long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: The obesity paradox? J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:578-84. [ Links ]

15. Garcia-Cano J, González Martín JA, Morillas Ariño J, et al. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A study in a small ERCP unit. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004;96:163-73. [ Links ]

16. Riesco-López JM, Vázquez-Romero M, Rizo-Pascual JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of ERCP in a low-volume hospital. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2013;105:68-73. [ Links ]

17. Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2117-27. [ Links ]

18. Cotton PB. How many times have you done this procedure, doctor? Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:522-3. [ Links ]