My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

Print version ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.108 n.7 Madrid Jul. 2016

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2016.4176/2015

Meta-analysis of the association between appendiceal orifice inflammation and appendectomy and ulcerative colitis

Peng Deng1 and Junchao Wu2

Departments of 1Emergency and 2Digestive Internal Medicine. West China Hospital. Chengdu, China

The authors thank West China Hospital for Excellent Technical Support.

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to investigate the relationship between appendiceal orifice inflammation (AOI) and appendectomy and ulcerative colitis (UC) by a meta-analysis.

Methods: Databases were thoroughly searched for studies on AOI and UC up to January 2016. Three comparisons were performed: a) whether the previous appendectomy was a risk factor of UC; b) influence of appendectomy on UC courses; c) influence of AOI on UC severity. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were the effects sizes. The merging of results and publication bias assessment were performed by using RevMan 5.3. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using Stata 12.0.

Results: Nineteen studies were selected in the present study. Results of comparison I showed that appendectomy was a protective factor of UC (OR = 0.44; 95% CI [0.30, 0.64]). Comparison II indicated appendectomy had no significant influence in the courses of UC (proctitis: OR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.74, 1.42]; left-sided colitis: OR = 1.01, 95% CI [0.73, 1.39]; pancolitis: OR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.59, 1.43]; colectomy: OR = 1.38, 95% CI [0.62, 3.04]). Comparison III indicated UC combined with AOI did not affect the courses of UC (proctitis: OR = 1.15, 95% CI [0.67, 1.98]; left-sided colitis: OR = 1.14, 95% CI [0.24, 5.42]; colectomy: OR = 0.36, 95% CI [0.10, 1.23]). Sensitivity analysis confirmed the robust of the results in the present study.

Conclusion: In conclusion, this meta-analysis indicated appendectomy can reduce the risk of UC. But appendectomy or AOI had no influence on the severity of the disease and the effect of surgical treatment.

Key words: Appendiceal orifice. Punctiform erosion. Ulcerative colitis.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including UC and Crohn's disease (CD), that affect 8 to 246 per 100,000 individuals (1,2). The classic characteristics are continuous and dispersive inflammation extending proximally from the rectum (3). The rectum, the rectosigmoid area, the left colon and the entire colon are common anatomic UC locations (4). It has been found that the number of patients with UC is on the rise year by year in our country, and UC contributes to developing cancers such as colorectal cancer (1). Extensive epidemiology studies on IBD have been conducted and its risk factors, such as familial aggregation, smoking habits and appendectomy, have been identified (5-7).

Cecal appendix has been repeatedly implicated in the pathogenesis and clinical course of UC (8). Appendectomy is strongly correlated with a decreased incidence of UC (9-12), indicating that appendicitis may have a relationship with UC. Furthermore, other studies showed that 71-88% of children with extensive UC had active inflammation in the appendiceal orifice (13,14). All these studies seem to draw attention to this skip-lesion change in UC. The clinical significance of appendiceal orifice inflammation (AOI) in UC has been extensively elucidated (15-17).

However, a different view supporting that AOI seems to have little prognostic implication for UC patients has been promoted (18). What is more, Ko et al. argue that appendectomy is a risk factor for UC among Middle Eastern migrants, while it is a protective factor among Caucasian populations (19). Besides, investigators have reported an inconsistent therapeutic effect on treating UC patients who were resistant to conventional medical therapy with appendectomy (20). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate whether AOI contributes to the development of UC.

In this study, we systematically retrieved the databases to identify the relevant studies. Then, we completed a meta-analysis with three comparisons to explore the relationship between AOI and UC.

Material and methods

This meta-analysis was presented in accordance with the guidelines of PRISMA.

Search strategy

PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library bibliographic databases were thoroughly searched up to January 2016. Manual document tracing was also conducted for relevant studies. The key words were ulcerative colitis (UC), appendiceal orifice inflammation (AOI), and appendectomy. The search strategy was ((ulcerative colitis) OR UC) AND ((appendiceal orifice inflammation) OR appendectomy). There was no restriction on the language.

Study selection

Two investigators (A and B) independently selected the study according to the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, a third investigator (C) was induced for discussion. The inclusion criteria were as follows: a) studies related to appendicitis and ulcerative colitis; b) the subjects were adults; and c) studies contained at least one of the outcomes. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a) duplicates; and b) studies whose outcome measures could not be obtained. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a) duplicates were excluded; and b) studies whose outcome measures could not be obtained were also excluded.

In addition, manual searching of the printed literature, reference lists of reviews and included studies were also performed for obtaining more relevant studies for the meta-analysis.

Data extraction and quality estimation

Authors A and B independently extracted the data, including first author, publication year, study type, country, patients (including time, groups, number and age of the subjects), and outcomes. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion with author C. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (21) was used for quality assessment, which was conducted by author B and C

Statistical analysis

There were three comparisons in this meta-analysis:

- Comparison I: UC patients vs. healthy control; outcome: previous appendectomy.

- Comparison II: UC patients under appendectomy vs. no appendectomy; outcomes: disease extent (proctitis, left-sided colitis, pancolitis), colectomy.

- Comparison III: UC patients AOI positive vs. AOI negative; outcomes: disease extent (proctitis, left-sided colitis), surgical therapy.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used as effect sizes. Cochran's Q test and I2 test (22) were used to assess heterogeneity among studies, with p < 0.05 or I2 > 50% indicating significant heterogeneity, and the random effects model was used for data merge; otherwise the fixed effect model was used. Publication bias was assessed by the funnel plot. All the statistical analyses were performed by using RevMan 5.3 software (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing one study each time. Stata 12.0 software was used for this process.

Results

Study selection

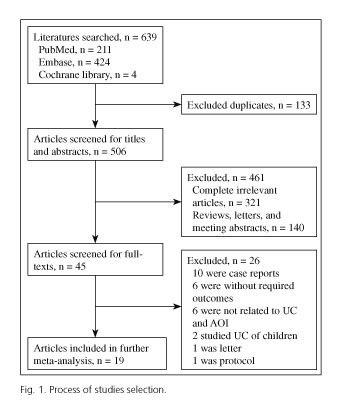

The procedures for the study selection are displayed in figure 1. We firstly found 639 studies (PubMed: 211; Embase: 424; Cochrane Library: 4). After removing 133 duplicates, 506 studies remained. Then, 321 completely unrelated studies and 140 reviews, letters or abstracts were excluded, and 45 articles remained. By screening of the full text, 19 studies were finally included in the present meta-analysis (5-7,15-17,19,23-34). The basic information of the selected studies is listed in tables I, II and III. All the studies had high quality with NOS 6-8.

The results of comparison I: appendectomy was a protective factor of UC

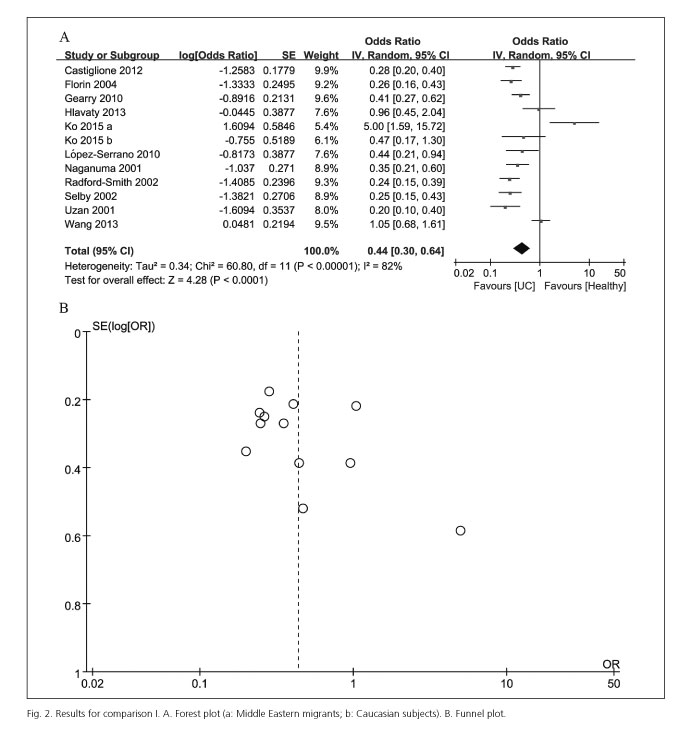

Comparison I was conducted among 11 studies (5-7,19,25,27,28,30-32,34) with 10,889 subjects (UC patients: 4,673; healthy control: 6,216).

There was significant heterogeneity (I2= 82%, p < 0.0001) among studies, thus the random effects model was chosen. The merged OR was 0.44 (95% CI [0.30, 0.64], p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A), indicating that appendectomy was a protective factor against UC.

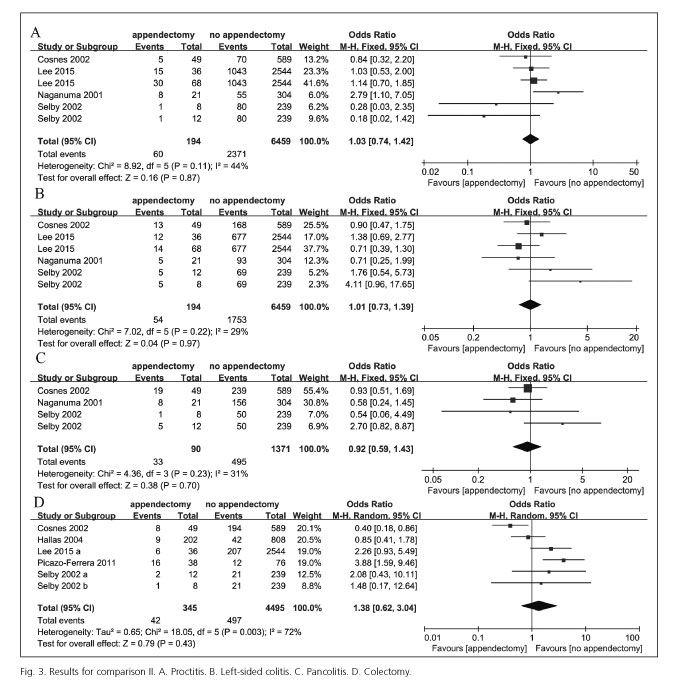

The results of comparison II: appendectomy did not affect the severity of UC

We further conducted comparison II to investigate the effects of appendectomy on the UC clinical course. Six studies (23,24,26,28,31,33) were involved in comparison II with 4,994 subjects (appendectomy: 434; no appendectomy: 4,560). These results were displayed in figure 3. There was no significant heterogeneity among studies on other outcomes of disease severity (proctitis, left sided colitis, pancolitis), excepting colectomy (I2 = 72%, p = 0.003). No significant differences were found in disease courses between UC patients with appendectomy and those without appendectomy (proctitis: OR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.74, 1.42], p = 0.87; left sided colitis: OR = 1.01, 95% CI [0.73, 1.39], p = 0.97; pancolitis: OR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.59, 1.43], p = 0.70; colectomy: OR = 1.38, 95% CI [0.62, 3.04], p = 0.43). This fact indicated that appendectomy did not affect the severity of UC.

Besides, subgroup analysis by the different time for appendectomy was performed (Table IV). The results showed that appendectomy before or after UC diagnosis did not statistically affect the severity of UC (p > 0.05); however, there was a report for both before/after UC diagnosis (33) showing a significant difference (p = 0.003).

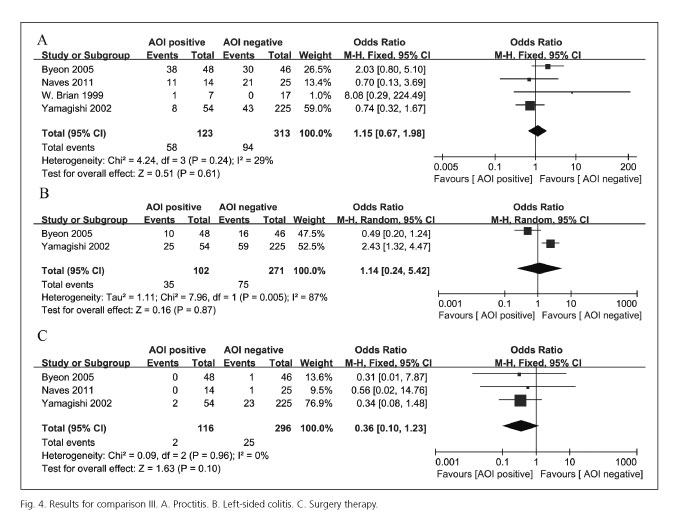

Results of comparison III: combined AOI did not affect the severity and surgical treatment rate of UC patients

The results of comparison III were shown in figure 4. The influence of combined AOI in the severity of UC was studied in four articles (15-17,29) including 436 subjects (AOI positive: 123; AOI negative: 313). There was significant heterogeneity among studies for left-sided colitis and the random effects model was used for merging of the effect sizes, while no heterogeneity was found among the studies for proctitis and the fixed effect model was used. Pooled results showed that there were no statistical significance in severity of UC between patients combined with AOI and those not combined with AOI (proctitis: OR = 1.15, 95% CI [0.67, 1.98], p = 0.61; left-sided colitis: OR = 1.14, 95% CI [0.24, 5.42], p = 0.87). Meanwhile, there was also no significant difference in surgical treatment rate for UC patients (OR = 1.36, 95% CI [0.10, 1.23], p = 0.10). These results indicate that combined AOI did not affect the severity and surgical treatment rate.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

No reverse occurred after removing any of the studies (data not shown), which indicates that the present results were robust.

The funnel plot of comparison I showed that there was no significant publication bias (Fig. 2B). Publication bias for other comparisons was not performed because of the limited amount of literature.

Discussion

This meta-analysis including 19 case-control studies comprehensively compared the influences of appendectomy and AOI in risk and severity of UC. The strengths of this study were the comprehensive analysis, the high quality of the studies included (NOS 6-8) and its robust results (sensitivity analysis). The results showed that appendectomy reduced the risk of UC but, as well as AOI, it did not affect its courses.

Firstly, comparison I confirmed that appendectomy was a protective factor of UC (OR = 0.44 [95% CI: 0.30-0.64], p < 0.0001). This is not consistent with the previous meta-analysis which indicated that the risk of CD, another IBD, significantly increased in the early years after appendectomy (RR = 1.99) (35). This disparity might be caused by the different mechanisms of the disease and the heterogeneity among studies. Heterogeneity in comparison I mainly comes from the study of Ko 2015a, which was performed among Middle Eastern migrants who were in a specific environment (19). Thus, we can still speculate that appendectomy or AOI may relate to the development of UC.

Scholars proposed that appendectomy before diagnosis only delayed the onset of UC but it did not reduce the risk (30). We therefore conducted comparison II to test whether appendectomy affected UC courses. The results indicated that in UC patients appendectomy did not affect the severity of UC and the need for surgery. This is consistent with the previous study, which implies that appendectomy protects against the development of UC but does not affect its course (36).

The influence of time between appendectomy and IBD diagnosis should be taken into account (35). In this study, subgroup analysis by appendectomy time was conducted and the results showed that appendectomy before or after UC diagnosis did not statistically affect the severity of UC. However, we did not stratify the time after UC diagnosis as the study conducted by Kaplan et al. did (35) due to the limited data, which is one of the disadvantages of the present study.

A long-term outcome study of Naves et al. (29) indicated that patients with AOI tend to present a mild course, and the chance to develop proximal progression of disease extent or colectomy was reduced. We finally analyzed the courses of UC in patients with AOI positive and AOI negative in comparison III. The meta-analysis of four studies, including the study by Naves et al. (2011) (29), indicated that there was no significant association between AOI and the extent of UC patient to develop proctitis, left-sided colitis and pancolitis, and the need of colectomy.

However, interpretation of the results in comparison III should be cautious due to the following reasons. First, the small sample size in comparisons II and III may influence the study conclusions; thus, it needs support from large-scale studies. Second, there were heterogeneities among studies for colectomy in comparison II and for left-sided colitis in comparison III. The possible sources, the difference in age when appendectomy was performed, the difference in subtypes of UC and the difference in nursing levels among diverse areas could affect the clinical courses and treatment of UC. Though the random effects model was used for merging effect sizes, there might also be influences in the observations.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis confirmed that appendectomy can reduce the risk of UC. But AOI or appendectomy had no influence on the severity of the UC disease and the effect of surgical treatment.

References

1. Klement G, Huang P, Mayer B, et al. Differences in therapeutic indexes of combination metronomic chemotherapy and an anti-VEGFR-2 antibody in multidrug-resistant human breast cancer xenografts. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:221-32. [ Links ]

2. Sugiyama Y, Saji S, Miya K, et al. Therapeutic effect of multimodal therapy, such as cryosurgery, locoregional immunotherapy and systemic chemotherapy against far advanced breast cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2001;28:1616-9. [ Links ]

3. Seroussi B, Bouaud J, Antoine EC. Users' evaluation of OncoDoc, a breast cancer therapeutic guideline delivered at the point of care. Proc AMIA Symp 1999:384-9. [ Links ]

4. Goldstone R, Itzkowitz S, Harpaz N, et al. Dysplasia is more common in the distal than proximal colon in ulcerative colitis surveillance. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:832-7. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.21809. [ Links ]

5. Castiglione F, Diaferia M, Morace F, et al. Risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases according to the "hygiene hypothesis": A case-control, multi-centre, prospective study in Southern Italy. J Crohns Colitis 2012;6:324-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.09.003. [ Links ]

6. Florin TH, Pandeya N, Radford-Smith GL. Epidemiology of appendicectomy in primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: Its influence on the clinical behaviour of these diseases. Gut 2004;53:973-9. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2003.036483. [ Links ]

7. Gearry RB, Richardson AK, Frampton CM, et al. Population-based cases control study of inflammatory bowel disease risk factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:325-33. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06140.x. [ Links ]

8. Inoue K, Tabei T, Suemasu K, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of pirarubicin cyclophosphamide and doxifluridine in advanced and metastatic breast cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1999;26:637-42. [ Links ]

9. Alexandre J, Faivre S, Sutherland W, et al. Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on the natural history and likelihood of therapeutic efficacy in advanced breast cancer patients: A critical literature review. Cancer Treat Rev 1998;24:393-406. DOI: 10.1016/S0305-7372(98)90002-0. [ Links ]

10. Valero V, Hortobagyi GN. Primary chemotherapy: A better overall therapeutic option for patients with breast cancer. Ann Oncol 1998;9:1151-4. DOI: 10.1023/A:1008427218935. [ Links ]

11. Namer M, Ramaioli A, Hery M, et al. Prognostic factors and therapeutic strategy of breast cancer. Rev Prat 1998;48:45-51. [ Links ]

12. Samarel N, Fawcett J, Davis MM, et al. Effects of dialogue and therapeutic touch on preoperative and postoperative experiences of breast cancer surgery: An exploratory study. Oncol Nurs Forum 1998;25:1369-76. [ Links ]

13. Elstner E, Williamson EA, Zang C, et al. Novel therapeutic approach: Ligands for PPARgamma and retinoid receptors induce apoptosis in bcl-2-positive human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2002;74:155-65. DOI: 10.1023/A:1016114026769. [ Links ]

14. Huber S, Ulsperger E, Gomar C, et al. Osseous metastases in breast cancer: Radiographic monitoring of therapeutic response. Anticancer Res 2002;22:1279-88. [ Links ]

15. Byeon JS, Yang SK, Myung SJ, et al. Clinical course of distal ulcerative colitis in relation to appendiceal orifice inflammation status. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005;11:366-71. DOI: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000164018.06538.6e. [ Links ]

16. Perry WB, Opelka FG, Smith D, et al. Discontinuous appendiceal involvement in ulcerative colitis: Pathology and clinical correlation. J Gastrointest Surg 1999;3:141-4. DOI: 10.1016/S1091-255X(99)80023-7. [ Links ]

17. Yamagishi N, Iizuka B, Nakamura T, et al. Clinical and colonoscopic investigation of skipped periappendiceal lesions in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:177-82. DOI: 10.1080/003655202753416849. [ Links ]

18. Park SH, Loftus EV Jr, Yang SK. Appendiceal skip inflammation and ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59:2050-7. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-014-3129-z. [ Links ]

19. Ko Y, Kariyawasam V, Karnib M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease environmental risk factors: A population-based case-control study of Middle Eastern migration to Australia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1453-63e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.045. [ Links ]

20. Selby WS, Griffin S, Abraham N, et al. Appendectomy protects against the development of ulcerative colitis but does not affect its course. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2834-8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07049.x. [ Links ]

21. Wells G, Shea B, O'connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000. [ Links ]

22. Higgins J, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [ Links ]

23. Cosnes J, Carbonnel F, Beaugerie L, et al. Effects of appendicectomy on the course of ulcerative colitis. Gut 2002;51:803-7. DOI: 10.1136/gut.51.6.803. [ Links ]

24. Hallas J, Gaist D, Vach W, et al. Appendicectomy has no beneficial effect on admission rates in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 2004;53:351-4. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2003.016915. [ Links ]

25. Hlavaty T, Toth J, Koller T, et al. Smoking, breastfeeding, physical inactivity, contact with animals, and size of the family influence the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: A Slovak case-control study. United European Gastroenterol J 2013;1:109-19. DOI: 10.1177/2050640613478011. [ Links ]

26. Lee HS, Park SH, Yang SK, et al. Appendectomy and the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: A retrospective cohort study and a nested case-control study from Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:470-7. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.12707. [ Links ]

27. López-Serrano P, Pérez-Calle JL, Pérez-Fernández MT, et al. Environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel diseases. Investigating the hygiene hypothesis: A Spanish case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2010;45:1464-71. DOI: 10.3109/00365521.2010.510575. [ Links ]

28. Naganuma M, Iizuka B, Torii A, et al. Appendectomy protects against the development of ulcerative colitis and reduces its recurrence: Results of a multicenter case-controlled study in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1123-6. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03757.x. [ Links ]

29. Naves J E, Lorenzo-Zuniga V, Marín L, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with distal ulcerative colitis and inflammation of the appendiceal orifice. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2011;20:355-8. [ Links ]

30. Radford-Smith GL, Edwards JE, Purdie DM, et al. Protective role of appendicectomy on onset and severity of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gut 2002;51:808-13. DOI: 10.1136/gut.51.6.808. [ Links ]

31. Selby WS, Griffin S, Abraham N, et al. Appendectomy protects against the development of ulcerative colitis but does not affect its course. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2834-8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07049.x. [ Links ]

32. Wang YF, Ou-Yang Q, Xia B, et al. Multicenter case-control study of the risk factors for ulcerative colitis in China. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:1827-33. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1827. [ Links ]

33. Picazo-Ferrera K, Bustamante-Quan Y, Santiago-Hernández J, et al. The role of appendectomy in the ulcerative colitis in Mexico. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2011;76:316-21. [ Links ]

34. Uzan A, Jolly D, Berger E, et al. Protective effect of appendectomy on the development of ulcerative colitis. A case-control study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2001;25:239-42. [ Links ]

35. Kaplan GG, Jackson T, Sands BE, et al. The risk of developing Crohn's disease after an appendectomy: A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2925-31. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02118.x. [ Links ]

36. Selby WS, Griffin S, Abraham N, et al. Appendectomy protects against the development of ulcerative colitis but does not affect its course. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2834-8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07049.x. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Junchao Wu.

Department of Digestive Internal Medicine.

West China Hospital.

Guoxue lane, 37.

610000 Wuhou District. Chengdu, China

e-mail: nojunchao@163.com

Received: 20-12-2015

Accepted: 05-02-2016