INTRODUCTION

Over the past 20 years, the introduction of biological agents into the clinical practice is one of the major advancements in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), such as Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) 1. Tumor necrosis factor alfa (TNF-α) antagonists such as infliximab 2, adalimumab 3 and golimumab 4) have changed the natural course of the disease 5. Despite the undoubted efficacy of biological therapy, these biological agents are much more expensive than traditional treatments. This imposes a considerable burden on the national healthcare system 6. However, many biological products have reached or are close to patent expiration. This has led to the development of biosimilar drugs. The biosimilar agents are highly similar in terms of quality, efficacy and safety to already licensed biologics 7 but can potentially result in a discounted cost of 20% to 70%. Therefore, offering considerable cost-savings to the healthcare systems 8.

CT-P13 (Remsima(r) and Inflectra(r)) was the first biosimilar of infliximab approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) 9 in September 2013. Then by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) 10 in April 2016, for all indications of the originator product including IBD. The extrapolation of the use of the biosimilar, infliximab, was based on two pivotal clinical trials in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The efficacy and pharmacokinetic equivalence of CT-P13 and infliximab RP were demonstrated in two randomized trials at 30 weeks. The safety profiles were comparable for both infliximab formulations 11,12. Results up to week 54 demonstrated a continued comparability between CT-P13 and the reference product 13,14. Furthermore, in extensions of these studies, similar efficacy and safety profiles were observed in patients with RA and AS who switched from RP to CT-P13 for an additional year, compared with those who continued CT-P13 treatment for two years 15,16.

In patients with IBD, a number of observational studies and real-life cohorts in anti-TNF α -naïve patients 17,18,19,20,21,22 and those who have been switched from infliximab RP 23,24,25,26,27 have shown good results in the past two years. Furthermore, results from the randomized, phase IV, double-blind, parallel-group NOR-SWITCH study (NCT02148640) have been recently reported. This trial demonstrated that switching from infliximab RP to CT-P13 was not inferior to continued treatment with infliximab RP 28.

The European Crohn's Colitis Organisation (ECCO) published its position statement on the use of biosimilars for IBD in December 2016 29. This states that "when a biosimilar product is registered in the European Union, it is considered to be as efficacious as the reference product when used in accordance with the information provided in the Summary of Product Characteristics".

Until data from randomized controlled trials in CD and UC are available, results from the "real-life" clinical use of the biosimilar can offer valuable insights into its efficacy and safety. The main aim of this observational study was to assess the effectiveness and safety of switching from infliximab RP to CT-P13 in patients with IBD for up to 12 months in clinical practice conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a multicenter observational study conducted at the Hospital Virgen Macarena and Hospital Juan Ramon Jiménez (Seville-Huelva, Spain) from 2016 to 2017. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Virgen Macarena and Hospital Juan Ramon Jiménez. Good clinical practice guidelines were followed and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patients

Patients with CD or UC who had previously been treated with infliximab RP were included in the study. The Montreal classification status was recorded in all patients before enrolment. All patients had switched from infliximab RP (Remicade(r)) to CT-P13 and were treated according to the dosage and regime recommended by the Summary of Product Characteristics of Remsima(r) in Spain 30.

Study endpoints and assessments

The efficacy endpoint was the change in clinical remission in patients who switched from infliximab RP to CT-P13 which was assessed at 12 months. With regard to patients with CD and UC in remission at the time of switching, remission was considered if the patient remained in clinical remission (HB score ≤ 4 in patients with CD or partial Mayo score ≤ 2 in patients with UC) without the need for steroids, surgery or an increased dose at the established follow-up time. In patients with CD and UC who were not in remission at the time of the drug switch, remission was considered if patients achieved a HB score ≤ 4 for CD and a partial Mayo score ≤ 2 for UC. The value of the HB score, the partial Mayo score and the C-reactive protein (CRP) at the drug switch time was compared with their respective value after 12-months of follow-up. Adverse events (AE) were monitored from the first infusion of CT-P13 until the end of the study and were recorded according to the Office of Human Research Protection 31.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and nominal results were reported as percentages and frequencies. Numerical results were reported as an average and standard deviation in cases of a normal distribution and as a median and interquartile range in the cases of a skewed distribution. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the clinical scores (HB score and partial Mayo score) and CRP values of patients; 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated and α was set at 0.05 for the determination of statistical significance. Analyses were performed using the SPSS 23 (IBM Corporation).

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 167 patients with IBD (116 with CD and 51 with UC) were included in the study. The median (range) age of patients with CD was 40.5 (28-54) years and 46 (34-58) years for patients with UC; 51% were female and 65% were non-smokers. The baseline demographics and phenotypic characteristics of patients with CD and UC according to the Montreal Classification and prior to medication exposure are shown in Table 1.

Efficacy

Basal remission was 87.4% (146/167) and 71.7% (109/152) after 12-months follow-up. The loss of efficacy at the end of the study was 15.7%. In total, 9% (15/167) of patients discontinued CT-P13 during follow-up. Data was analyzed by an intention to treat analysis with a 12-month follow-up remission of 69.5% (116/167) (p > 0.05). The loss of efficacy by the intention to treat analysis post switch was 17.9% (p > 0.05).

CD patient group

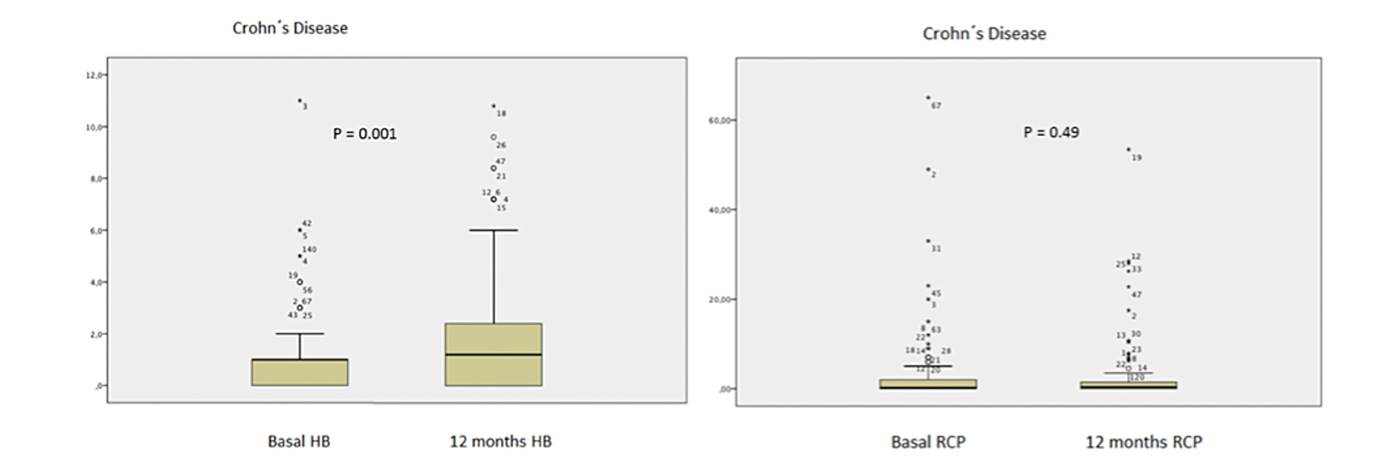

Ninety-four per cent (109/116) of patients with CD completed 12 months of follow-up. Seven patients stopped treatment; four due to AE, two due to maintained remission with mucosa healing and one did not attend follow-up visits. At the start of the study, 88.8% (103/116) of patients with CD were in remission. After switching from infliximab RP to CT-P13, 69.7% (76/109) were in remission after 12 months and the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1). In addition, 68.9% (71/103) of patients with basal remission maintained the remission after 12 months follow-up (p > 0.05). Remission at the end of the study was 67.2% (78/116) (p > 0.05) according to the intention to treat analysis. The HB score significantly changed over the 12-month period; the median HB score was 1 (0-1) vs 1 (0-2) at baseline and 12 months, respectively (p = 0.001). No significant changes in the median CRP levels were observed in patients with CD during the same period, 0.20 (0-2) vs 0.22 (0-0.80) at 0 and 12 months, respectively, (p = 0.49) (Fig. 2).

UC patient group

In relation to patients with UC, 84.3% (43/51) completed 12 months of follow-up. Eight patients stopped treatment; three due to AE and five due to maintained remission with mucosa healing. At the start of the study, 84.3% (43/51) of patients with UC were in remission. After switching from infliximab RP to CT-P13, 76.7% (33/43) were in remission after 12 months; the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1). Also, 72.1% (31/43) of patients with basal remission maintained the remission at 12 months follow-up (p > 0.05). Finally, 74.5% (38/51) of the patients remained in remission after 12-months of follow-up (p > 0.05) according to the intention to treat analysis. No significant changes in the median partial Mayo score were observed in switched patients at 12 month, 1 (0-2) vs 1 (0-2) at 0 and 12 months, respectively (p = 0.87). Significant changes in the median CRP level were observed during the same period, 0.8 (0-4) vs 0.23 (0-0.58) at 0 and 12 months respectively (p = 0.003) (Fig. 3).

Safety

With respect to safety, 12/167 (7.2%) AEs occurred during the study; one skin reaction, one case of abdominal pain, two cases of headaches and two cases of paresthesia during infusion, one case of Sweet's syndrome, two of polyarthralgia, two of palpitations and one neoplasia. Seven patients (58.3%) discontinued treatment due to the AEs. Three AEs were considered as serious AEs. One patient with CD who had Sweet's syndrome needed to be hospitalized and discontinued treatment, and one patient with UC had severe paresthesia during the infusion. In addition, one patient developed a meningioma during the follow-up and consequently discontinued treatment, although the relationship between this neoplasia and the anti-TNF therapy has not been described.

DISCUSSION

Long-term data from randomized controlled trials of CT-P13 for CD and UC are not available. The results from its use in the clinical practice can provide valuable information related to the efficacy and tolerability of the biosimilar in these scenarios. The response patients with IBD at twelve months after switching to CT-P13 from infliximab RP was analyzed in this multicenter prospective observational study. The results indicate that CT-P13 treatment is effective and safe for up to one year in patients that have switched from infliximab RP and are in line with other recently published studies 25,26,27. At 12 months, the remission was maintained in 69.7% of patients with CD and 76.7% of patients with UC. Thus, global loss of efficacy with CT-P13 at 12 months was 15.7%. With regard to patients in basal remission, 68.9% of CD patients and 72.1% of UC patients maintained the basal remission after 12 months follow-up. There were no statistically significant differences compared to basal remission. There were significant changes in HB score in CD patients. However, the median overall score still remained within the definition of remission (≤ 4). No significant changes in the median partial Mayo score were observed in UC patients. There were no clinically relevant changes in CRP levels in both groups.

Anti-TNF-α therapy is effective for the induction and maintenance of remission in IBD. The efficacy was demonstrated in the ACCENT I trial 32 in patients with active CD; the clinical remission rate at week 54 was significantly higher in week 2 responder patients that received IFX 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg compared with the placebo group (28% and 38% versus 14%). However, many patients who initially respond to these treatments later experienced a loss of efficacy with a concomitant flare-up of symptoms. A review by Gisbert et al. 33 and Chaparro et al. 34 found that 37% of patients with CD stopped responding to infliximab and calculated an annual risk of a response loss of 13-15% per patient/year. Most of these patients required increased doses or had to switch to another anti-TNF-α medication.

In the ACT I and II trials, approximately 45% of patients with UC had a sustained response to infliximab at week 54, meaning that 55% of patients stopped responding during the year 35,36. The results of the current study support these previous findings. In our study, patients switched from infliximab RP to CT-P13 and the clinical response was monitored for 12 months. There are very few similar studies in order to compare our results. Smith et al. 25 reported a study of 83 patients, 57 with Crohn's disease, 24 with ulcerative colitis and two with unclassified IBD. Sixty-eight patients completed one-year follow-up. Global clinical remission rates were 53/83 (64%) at baseline and 61/83 patients (73%) at week 52. Our results are similar.

The NOR-SWITCH trial 28 included patients with IBD (155 CD and 93 UC) who switched from infliximab RP to CT-P13, as well as patients with RA, spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis and chronic plaque psoriasis. The deterioration rate in patients with CD was 36.5% and 11.9% for UC cases. The disease deterioration occurred more frequently in CD patients. This trial was not powered to assess changes within each indication, thus, these results must be interpreted with caution. However, our results demonstrated a loss of efficacy of 17.9% in patients with basal remission; 19.9% in CD and 12.2% in UC. These are also in line with the NOR-SWITCH analysis.

In the PROSIT-BIO study 37, 313 Crohn's disease and 234 ulcerative colitis patients were enrolled, and only 97 switched to CT-P13. The efficacy estimations were 95.7%, 86.4% and 73.7% for naïve cases, 97.2%, 85.2%, and 62.2% for pre-exposed cases and 94.5%, 90.8%, and 78.9% for drug switch cases at eight, 16, and 24 weeks, respectively. Adverse events were reported in 12.1% of cases; 38 (6.9%) were infusion-related reactions.

The recently published systematic review with a meta-analysis 38 demonstrated high rates of sustained clinical response in CD patients that switched from infliximab RP to CT-P13 at 30-32 weeks (0.85, 95% CI = 0.71-0.93) and 48-63 weeks (0.75, 95% CI = 0.44-0.92). In addition, there were high rates of a sustained clinical remission of 0.74 (95% CI = 0.55-0.87) and 0.92 (95% CI = 0.38-0.99) at 16 weeks and 51 weeks, respectively. The sustained clinical response in UC were 0.96 (95% CI = 0.58-1.00) and 0.83 (95% CI = 0.19-0.99) at 30-32 weeks and 48-63 weeks, respectively. The sustained clinical remission in UC were 0.62 (95% CI = 0.42-0.78) and 0.83 (95% CI = 0.19-0.99) at 16 weeks and 51 weeks, respectively. However, data with regard to switching from infliximab RP to a biosimilar were limited. In fact, the pooled rates for remission up to 16 weeks included only two studies of CD and one study of UC. There was only one study of CD and UC at week 51, both of which included a small number of patients. All observational post-marketing studies published to date have reported positive outcomes of efficacy measures in patients with CD and UC treated with CT-P13, irrespective of prior anti-TNF-α treatment 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28.

In the current study, AEs occurred in 12/167 (7.2%) patients with IBD; 3% 5 were infusion-related reactions (one skin reaction, two headaches and two of paresthesia during infusion). One patient developed a meningioma during follow up. There is no data with regard to a correlation between anti-TNF therapy and this type of neoplasia. However, this patient discontinued treatment. To date, no unexpected treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) have been reported in patients with CD and UC treated with CT-P13 (19-28). Adverse events were rare (CD, 0.10, 95% CI = 0.02-0.31; UC, 0.22, 95% CI = 0.04-0.63) in a systematic review with a meta-analysis 38. There was a significant positive correlation between the proportion of patients with prior anti-TNF-α treatment and the risk of infusion.

In 2013, the Spanish Society of Gastroenterology and Spanish Society of Pharmacology published its position statement about biosimilars. They indicated that the appropriate use of biosimilar drugs requires an interaction between physicians, pharmacists and regulatory agencies, with the aim of favoring the right to health of patients by offering quality, effective, and safe products. This task force favors the development of biosimilar drugs and therefore, their approval by regulatory agencies, provided that they are subjected to quality standards as supported by these agencies in terms of production and development. As well as an assessment of their efficacy and safety 39.

Our study has some limitations. First of all, and perhaps most importantly, there is no non-switch patient arm. Similarly, we could not measure drug trough levels or the presence of antidrug antibodies, as has been performed in other studies. Therefore, it was not possible to ascertain the cause of the loss of response observed in some patients. We were also unable to measure mucosal healing, or fecal calprotectin as a biomarker of relapse in patients with IBD.

Although there are limitations in our study, we believe that it shows real data in the clinical practice during one-year of follow-up. These results are the first presented in Spain that prove the safety of CT-P13 for the treatment of patients with IBD. Similar remission rates were achieved with the current treatment with infliximab and no important adverse effects were reported. This study could open a new field of study in IBD and new studies with a longer follow-up time are required to corroborate our results.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable data on the long-term efficacy of CT-P13 maintenance treatment after switching from infliximab RP. Our results have demonstrated a good clinical efficacy and safety at 12 months in real-life clinical practice. The loss of efficacy at 12 months was 15.7%, similarly to that reported for the reference product, infliximab.