BACKGROUND

Common bile duct stone (CBDS) removal is one of the main indications for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). However, stones cannot be removed on some occasions with conventional techniques due to their large size or difficult location. Furthermore, CBDS can be missed or misinterpreted by standard retrograde cholangiography 1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Besides CBDS, biliary strictures (BS) are the second most frequent cause for the use of ERCP. BS diagnosis using either biliary brush cytology or forceps-biopsies cannot distinguish between malignant and benign etiologies in around 50% of cases 2,8,9.

Smaller-caliber endoscopic equipment has been developed to overcome these limitations. In 1975, peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy began with the mother-baby system. This endoscopic technique enabled direct visual examination, tissue sampling and the treatment of difficult biliary and pancreatic stones 6,10,24. Nevertheless, the use of this device has some limitations 9,25 ,51) . The SpyGlass(tm) Direct Visualization System, a single-operator cholangiopancreatoscope (SOCP) for peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy, was released in 2006 26. The system includes a reusable optical probe and a small 3.3 mm catheter (SpyScope(tm)) with a four-way tip deflection and a separate irrigation and working channel that accesses pancreatic and biliary ducts.

In 2015, the upgraded SpyGlass(tm) Digital System was released. Compared to its legacy version, the DS has a digital sensor with a higher resolution, wider field of view, automatic light control and LED illumination. In the current study, we aimed to assess the usefulness, efficacy and safety of the single-operator-cholangiopancreatoscopy (SOCP) with the SpyGlass(tm) system for the management of biliopancreatic diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patients

A retrospective, single-center cohort study of patients with biliopancreatic diseases who were referred to our endoscopic unit for ERCP from September 2008 to April 2016 was performed. The SpyGlass(tm) was chosen as a second-line procedure following an unsuccessful ERCP via standard techniques, for the diagnostic and therapeutic management of indeterminate strictures and large stones in the biliary and pancreatic ducts. The study was approved by the institutional ethics review board at our institution.

Equipment and technique

The SpyGlass(tm) legacy was used to perform cholangioscopy-guided biopsies between September 2008 and March 2015. The SpyGlass(tm) DS was used from March 2015 to April 2016. The DS is a single-use system that replaces the legacy fiber-optics with a digital sensor.

A Northgate Autolith IEHL generator with a 0.66 mm biliary probe was used for electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL). Cholangioscopy-guided tissue sampling was performed using the SpyBite(tm) mini-forceps. All procedures were performed under deep sedation, controlled by an anesthesiologist. Intravenous antibiotics were administered in all cases where a biliary obstruction was suspected. Biliary sphincterotomy was performed in all cases when it had not been performed previously. Pancreatic sphincterotomy was also performed in all pancreatoscopy cases. In order to perform the cholangiopancreatoscopy, the SpyScope(tm) was attached to the duodenoscope and inserted through the 4.2 mm therapeutic working channel (TJF-180V; Olympus). In the majority of cases, the SpyGlass(tm) was inserted over a previously placed guidewire in the duct of interest (common bile duct or main pancreatic duct). Aspiration of detritus and irrigation with sterile saline was required while the system was being inserted through the papilla. Endoscopic images were obtained on the same monitor by alternating between them. Two different views are available to the endoscopist on two different screens, the duodenoscope image and the SpyGlass(tm) view. Samples were collected using the SpyBite(tm) biopsy forceps and were processed according to standard histological protocols.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were technical and complete success of the procedure. Technical success was defined as the ability to reach the lesion using the cholangioscopy system. Complete success was defined differently for specific biliary lesions. In cases of biliary strictures, a complete success of the procedure was defined as the ability to reach the lesion, adequately visualize it and implement the appropriate diagnostic or therapeutic technique (biopsy, passage of the guidewire, or dilation). For biliary stones, complete success was defined as the ability to access the stone and to perform lithotripsy.

Secondary outcomes

The main secondary outcome of the study was to determine the sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic diagnosis, compared to the histological diagnosis. Endoscopic diagnosis was performed by visualizing the mucosa at the site of the stricture. Lesions were endoscopically diagnosed as malignant if they had characteristic features, such as tumor-like vessels (irregular, dilated, and tortuous blood vessels), intraductal nodules or masses, irregular surfaces with papillary areas or spontaneous bleeding 6,27,28,29. The final diagnosis was determined based on the histological findings of the lesion and/or follow-up imaging. Targeted biopsies were obtained using SpyBite(tm), endoscopic ultrasonography or surgery. Biopsy samples were evaluated by a gastrointestinal pathologist and were classified into the following categories: suspected malignant, benign or insufficient to establish a diagnosis. In the absence of a definitive histological diagnosis, the diagnosis was considered as malignant when there was clinical deterioration and progression of the lesions after follow-up imaging. Lesions were defined as benign when biopsies were negative for malignancy and there was no clinical and radiological progression after six months of follow-up.

Additional secondary outcomes included total procedure time and total SOCP time. The total procedure time was measured from the time of insertion of the duodenoscope to its withdrawal and also included the time required to perform the ERCP and SOCP. The time of SOCP was defined from insertion of the SpyScope(tm) into the duodenoscope working channel to the withdrawal of the SpyGlass(tm) system from the duodenoscope.

The adequacy of the visualization of the procedure was assessed. The visualization quality was graded on a four-point scale as follows. Poor (one point): deficient visualization due to the presence of content that cannot be washed or aspirated away or caused by defects in the system operation, which precludes an adequate visualization of the bile duct and pancreatic duct and the definite identification of any abnormalities or stones. Regular (two points): the existing abnormalities are not clearly observed but are sufficiently defined to suspect abnormalities. Good (three points): the lesions can be clearly and correctly differentiated. Excellent (four points): the vascularization and duct wall abnormalities can be visualized with high definition. Adequate visualization was defined as a score of 3 or above.

Safety was our final secondary outcome. Adverse events were prospectively evaluated either at the end of the procedure or during follow-up, in the emergency room or during the hospitalized period.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are shown as means (SD) or medians (range). Categorical variables are shown as frequencies and percentages. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively) and overall diagnostic accuracy were calculated compared to the final diagnosis. The Student's t-test and Chi-square tests were used to compare continuous and qualitative variables, respectively. p values ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v19.0 software.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

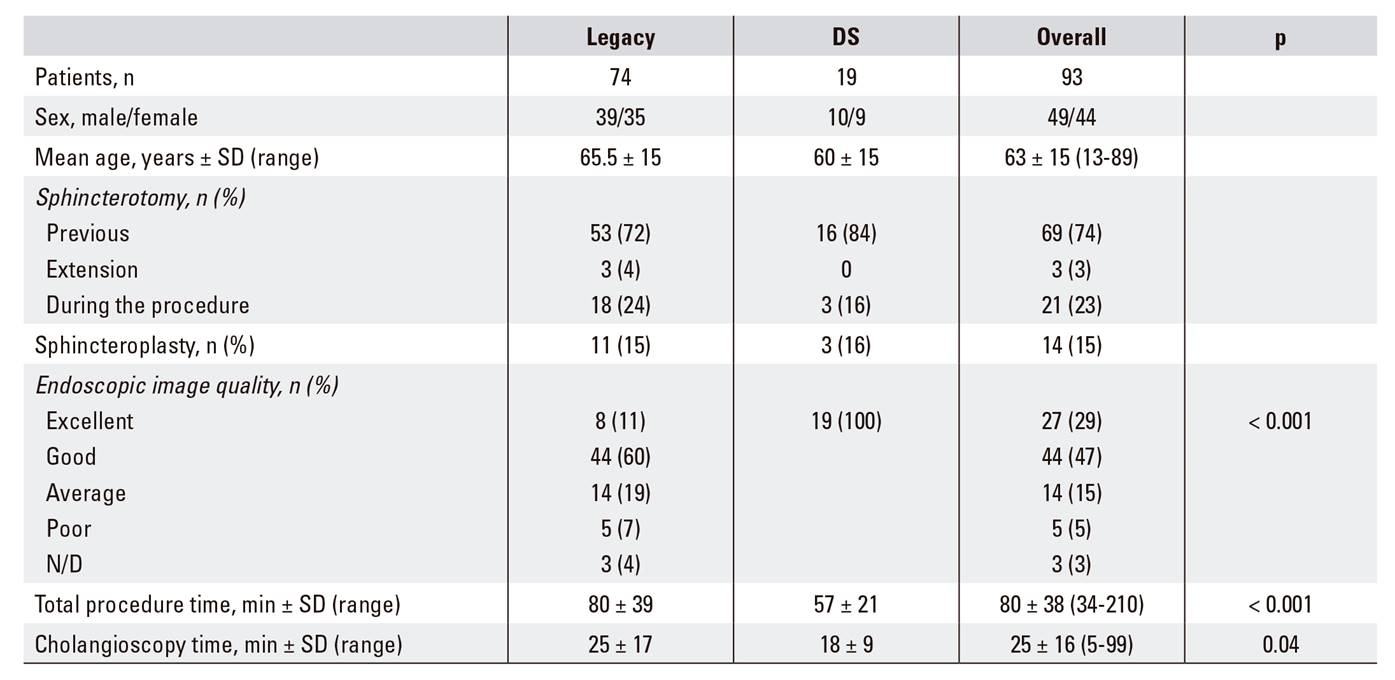

During the period, 1,858 ERCP were performed. SpyGlass(tm) was applied in 107 procedures in 93 patients (5.7%). The mean age of patients was 65 years (± 15 years) and 51% of patients were female. Technical success was achieved in 90 cases (97%) and complete success in 82 cases (88%), as shown in Table 1.

Diagnostic cholangioscopy in indeterminate lesions

Fifty-six procedures were performed in 52 patients with the aim of categorizing indeterminate biliary lesions. The procedure was repeated in four patients as a definitive diagnosis was not reached. Technical success was achieved in 49/52 (94%) patients. Technical success was not achieved in two cases due to the presence of strictures in the distal bile duct (one cholangiocarcinoma and one pancreatic adenocarcinoma), which did not allow for the safe insertion of the cholangioscopy system. Technical success was also not achieved in one patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), as access to the lesion was not possible due to a narrow bile duct diameter. Complete success was achieved in 45/52 (85%) of cases. Four clinical failures also occurred. In two patients, a guidewire could not be placed through the stricture using the DS SpyGlass(tm) and stricture dilation could not be achieved in another case. The lesion could not be assessed due to poor visualization using the legacy SpyGlass(tm) system in one case. Diagnosis was achieved by cholangioscopy or cholangiogram in the cases of technical failure.

Sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic diagnosis

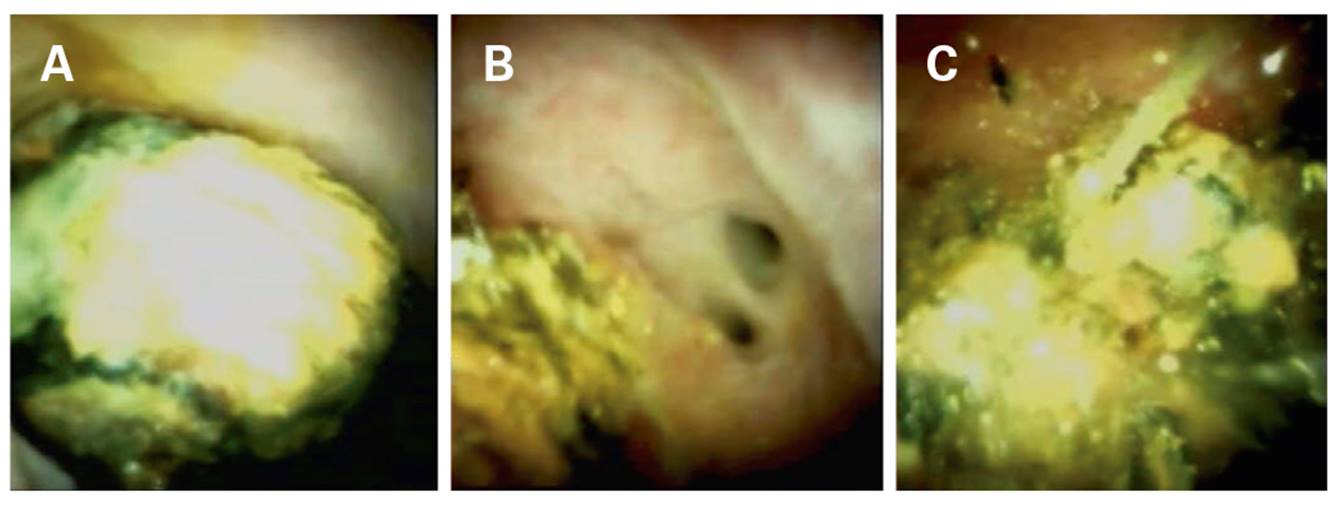

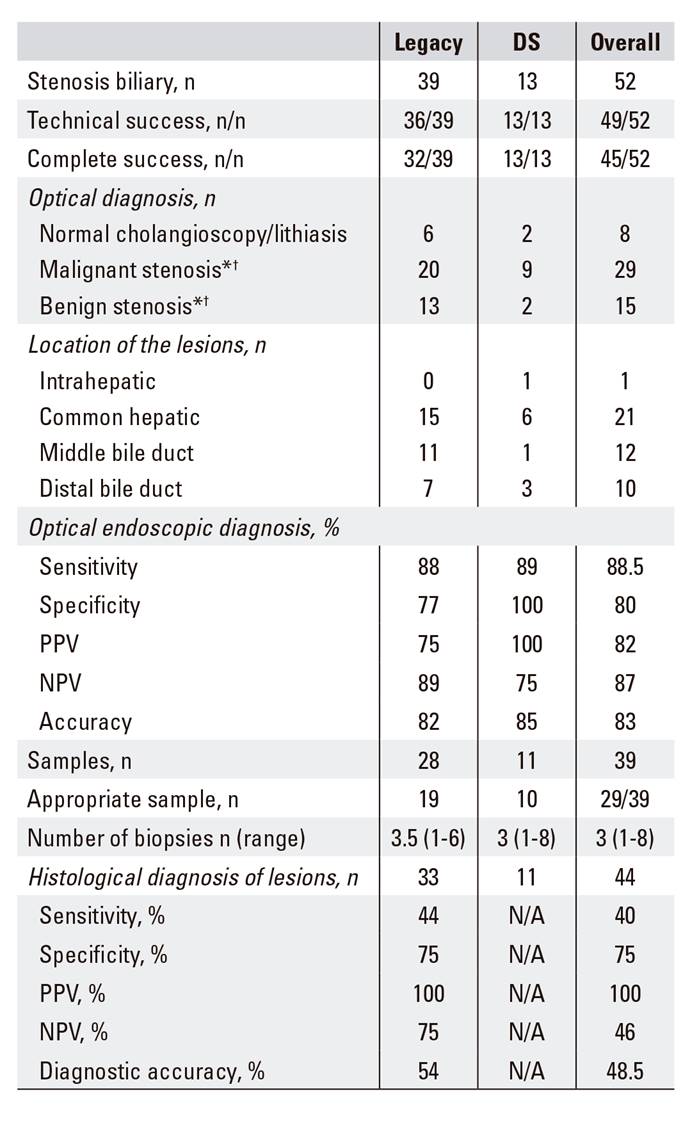

Forty-four patients were diagnosed with indeterminate bile duct lesions after excluding patients with a normal cholangioscopy or those diagnosed with cholelithiasis (Fig. 1). Twenty-three of these cases were considered as malignant after cholangioscopic diagnosis and the final diagnosis confirmed malignancy in 26 patients (50%). The cholangioscopic diagnosis are summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 1 A. An indeterminate biliary stricture visualized by cholangioscopy with spontaneous bleeding and tortuous vessels which are suggestive of a cholangiocarcinoma. B. Biopsies taken at the site of a biliary stricture with forceps (SpyBite(tm)).

The endoscopic sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy for the detection of malignancy were 88%, 80% and 83%, respectively. Four patients who were diagnosed with a bile duct malignancy via endoscopy had a benign final diagnosis (using the gold standard test). In addition, three patients who were diagnosed endoscopically with benign lesions had a bile duct malignancy that was discovered by histopathological analysis. All endoscopic diagnostic errors occurred using the legacy SpyGlass(tm) series.

Sensitivity and specificity of histological diagnosis

Table 2 Indeterminate bile duct stenosis procedure characteristics

N/A: not applicable. *†A diagnosis was made using the cholangiographic images for cases in which the SpyGlass(tm) could not be inserted (lithiasis, malignant stenosis consistent with cholangiocarcinoma, or stenosis of extrinsic origin consistent with pancreatic adenocarcinoma). The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV or diagnostic accuracy could not be calculated using the DS system, as benign lesions were not biopsied. Thus, there were only biopsies of malignant tumors or suspected of being malignant.

Biopsies were performed in 34 (77%) patients, with a mean of four biopsies per patient (range 1-8). Biopsies were not obtained in ten cases (23%) as the endoscopic diagnosis was benign. The biopsy samples were considered as adequate in 24 (71%) cases. The overall sensitivity and specificity of the histological diagnosis was 40% and 75%, respectively, with a diagnostic accuracy, NPV and PPV of 48.5%, 100% and 46%, respectively. In cases where four or more biopsies were obtained, the sensitivity and specificity was 54% and 87.5%, respectively, compared to 29% and 80% in the cases where fewer than four biopsies were obtained. For the procedures in which four or more biopsies were obtained, the samples were insufficient in 2/16 (13%) cases versus 8/18 (44%) cases when less than four biopsies were obtained (p = 0.08).

Therapeutic cholangioscopy (CBDS and pancreatic stones)

Bile duct

Forty-one procedures were performed in 34 patients. Technical success was achieved in 34/34 (100%) patients and complete success was achieved in 31/34 (91%) cases. Complete success was not achieved in two cases as the stones were located in an intrahepatic location. With regard to patients with a complete success, the cleaning was completed within a single procedure in 20/31 (65%) of cases. Four cases were unsuccessful due to a large number of stones and seven cases were unsuccessful due to the large size of the stone (≥ 20 mm) (Fig. 2). EHL was applied in 16/34 (47%) patients. The mean bile duct stone size was 21 mm (range, 10-30 mm) and 81% of the patients had stones > 20 mm.

Pancreatic lithiasis

Pancreatoscopy was performed in seven patients diagnosed with chronic calcifying pancreatitis; four males and three females with a mean age of 51 years (range: 13-66 years). The majority of cases had a single stone with a mean measurement of 11 mm (range: 7-15 mm), which was located in the main pancreatic duct. EHL was employed in three cases and the technical and complete success of the procedure was 100% in both cases. We were able to complete the cleaning during only one procedure in four cases; two procedures had to be performed in two cases andthree procedures had to be performed in one case as the stones measured 15 mm or more (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 A. Image of an obstructive stone in the main pancreatic duct. B. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy. The lithotripsy probe is shown at the bottom of the image. C. Stone extraction with a balloon. D. Pancreatic duct following treatment: complete cleaning.

SpyGlass(tm) DS system sub-analysis

Of the 93 patients included in the study, 19 underwent cholangioscopy using the SpyGlass(tm) DS (13 indeterminate bile duct strictures, three therapeutic procedures in the bile duct and three in the pancreatic duct). The total procedure time was 57 minutes (± 21) and the cholangioscopy time was 18 ± 9 minutes. The technical and complete diagnostic success rates of the DS procedures performed to assess the indeterminate bile duct lesions were 100%. The visual diagnosis had a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 100%, a PPV of 100%, a NPV of 75% and an overall diagnostic accuracy of 91%. Biopsies were taken in 11/13 patients and only one of these samples was inadequate, compared with nine samples when using the legacy SpyGlass(tm) system (p = 0.228).

Safety

The incidence of adverse events was 7/93 (7.5%) and there were no differences between the DS and the legacy system (p = 0.7). There were four adverse events (7.7%) in the indeterminate bile duct strictures subgroup. These included one case of pancreatitis in a patient with PSC, one case of self-limiting hemorrhage, one case of cholecystitis caused by obstruction due to cholangiocarcinoma and one case of bile duct wall laceration in a patient with cholangiocarcinoma. There were three adverse events in the stone therapy group, which included hemobilia, lithotripter impaction in the bile duct that required surgery and moderate pancreatitis after pancreatic lithotripsy.

DISCUSSION

The main advantage of SOCP is its capacity to directly visualize biliary and pancreatic conditions, which facilitates an easier endoscopic diagnosis and therapeutic intervention. SOCP has been shown to be an effective tool for the diagnosis of indeterminate bile duct strictures and for treating biliopancreatic lithiasis 4,5. SOCP has a high technical success using both the legacy and DS systems (95% and 100%, respectively) in our institution. Past studies with brush cytology or intraductal fluoroscopy forceps biopsy demonstrated a highly disparate range (5.8% to 48%) for the determination of the type of biliary strictures 6,8,13,20,37,38. SOCP aids the visualization of lesions and biopsy acquisition from these sites, which may help to improve the sensitivity and reliability of the diagnosis.

A technical success rate of 94% was achieved using the legacy and DS version of the SpyGlass(tm) device in this study. However, the diagnosis obtained via SOCP in our study was subject to error, which is consistent with previously published findings 6,14,47. While there are no validated criteria available that enable the differentiation between malignant and benign endoscopic lesions in vivo, we used criteria defined in previous studies to perform an endoscopic diagnosis 6,27,35,36. There was a sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 80%, respectively, in our study, which are similar to those of recently published studies (84.5-95% and 79-92.6%, respectively) 6,22,31. Likewise, the DS system alone showed an enhanced diagnostic accuracy, a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 100% 32.

The main problem we experienced was an insufficient collection of biopsy material for a histological diagnosis. Adequate samples were obtained in only 73% of cases, which is somewhat lower than other series 6,20,22. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity of the histological diagnosis were also lower than those of similar published studies 31. While most studies report an average of 3-4 biopsy samples per case, an adequate histological diagnosis was always obtained when more than six biopsies were collected 14,29,39,40. In our study, the diagnosis sensitivity was 54% when four or more biopsies were obtained and only 29% when fewer than four biopsies were obtained. In our study, cases in which more than four biopsies were obtained were more likely to be considered as adequate (two versus eight, respectively). These results suggest that collecting more biopsy samples may improve diagnostic yield and avoid the need to repeat procedures.

The use of cholangioscopy-guided lithotripsy for the treatment of gallstones with ERCP usually significantly reduces the number of procedures required to completely clean the bile duct 7,13,14,21,29. We achieved technical and complete success rates of 100% and 91%, respectively, using this modality and achieved complete cleaning using a single procedure in 65% of cases. This is consistent with previous studies 20,21,48.

SOCP has also been shown to be effective for the management of chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Several studies have demonstrated a high rate of technical success and complete cleaning 20,24,48, which is similar to our data. A technical and complete success rate of 100% was achieved for the procedure in the seven patients included in this subset. In addition, complete cleaning using a single procedure was achieved in four patients. As SOCP reduces the number of sessions required to achieve a complete cleaning, this technique appears to be superior to extracorporeal lithotripsy 41,42. Moreover, SOCP has a low adverse event rate that is comparable to ERCP 2; this was 7.5% in our study, which is similar to previously published work 13,20,44,49. Our findings indicate that the updated SpyGlass(tm) DS appears to have several advantages over the legacy system. Although our study included only a limited number of patients, our results show that its use produced a significant reduction in the examination duration, which was probably related to the improved image quality and handling simplicity 20,45,46.

The main limitations of this study were its retrospective nature and the inclusion of patients referred from other centers who had previously undergone procedures involving bile duct manipulation. In addition, the limited number of patients included in the DS cohort hindered an adequate comparison of the two systems. Therefore, we conclude that SOCP, especially with the new DS, is a safe and useful technique to achieve an appropriate visual endoscopic diagnosis. Nevertheless, technical improvements are still needed. Sampling needs to be optimized to improve the histological diagnostic yield and the number of procedures required to achieve a complete cleaning in a single session should be further reduced to improve the capacity for biliopancreatic therapy.