Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versión On-line ISSN 2173-9161versión impresa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.27 no.4 Madrid jul./ago. 2005

Artículo Especial

The current state of treatment for cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck

Tratamiento de los melanomas cutáneos de la cabeza y el cuello. Estado actual

P.M. Villarreal Renedo1, J. Mateo Arias2, C. Álvarez Cuesta3, E. Rodríguez Díaz3, A. Fernández Bustillo4, A.J. Morillo Sánchez2

|

Abstract: Objective. To demonstrate our experience in the treatment

of head and neck cutaneous melanoma and the regional lymph nodes staging,

by the sentinel lymph nodes biopsy technique. Key words: Cutaneous melanoma; Head and Neck; Cervical Stage; Sentinel lymph node.

|

Resumen: Objetivo. Demostrar nuestra experiencia en el

tratamiento del melanoma cutáneo de cabeza y cuello, así como en el

estadiaje ganglionar regional a través de la detección y biopsia de los

ganglios centinelas cervicofaciales. Palabras clave: Melanoma cutáneo; Cabeza y cuello; Estadiaje cervical; Ganglio centinela. |

Recibido: 20 de enero de 2005

Aceptado: 22 de junio de 2005

1 Médico adjunto. Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Oviedo, España.

2 Médico adjunto. Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina de Badajoz, España.

3 Médico adjunto. Servicio de Dermatología. Hospital de Cabueñes. Gijón, España.

4 Cirujano Oral y Maxilofacial. Práctica privada. Pamplona, España.

Correspondencia:

Pedro Mª Villarreal Renedo

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial.

Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias.

C/ Celestino Villamil s/n - 33006- Oviedo (Asturias), España.

E-mail: pedrovillarreal@eresmas.com

Introduction

The cutaneous melanoma (CM) is an aggressive neoplasm, with a capricious and treacherous nature. It has a high cure rate if diagnosed rapidly, but for advanced stages the prognosis is gloomy.1,2 Of all the body surface, the head and neck are the areas with the greatest incidence and mortality rates as a result of CM.3 Here, a third (20-33%) of these tumors develop, even when this surface area only represents 9% of the organism.4,5

Surgery is the procedure of choice for CM of the head and neck. There is current debate as to the resection margins and the need for carrying out cervicofacial prophylactic/therapeutic lymph node dissection.1

The histopathologic state of the regional lymph nodes is considered today the main factor determining prognosis, more so than Breslows thickness, and for this reason staging should always be carried out.6 Those patients with metastatic disease of lymph nodes of the head and neck require cervical lymph node dissection. If there is metastasis of the periparotid or intraparotid lymph nodes, a parotidectomy should also be carried out. In those patients where there is no clinical/ radiological evidence of metastasis (T2, T3 and T4 N0) regional staging should be established by means of a selective lymphadenectomy of sentinel lymph nodes (SN) of the head and neck.

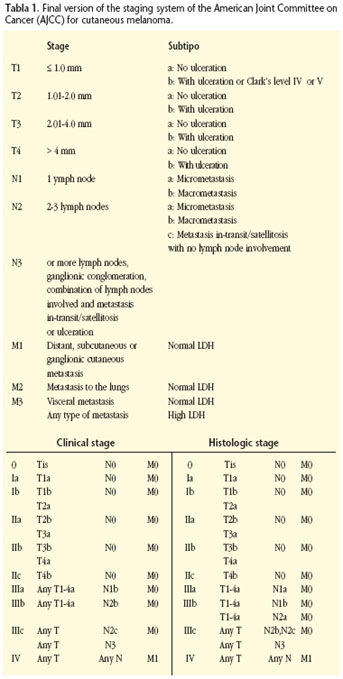

The detection, excision and biopsy of SN has become the procedure of choice for treating CM of the head and neck when there is no clear metastatic adenopathy. The technique allows carrying out more precise neck staging, as it is possible to detect the presence of subclinical or microscopic lymph node metastasis. Those patients requiring a lymphadenectomy and posterior adjuvant treatment are identified. 6,8,9,10,11Its relevance is so considerable that its results have been incorporated into the latest staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, Table 1).6

Objectives

To show our experience in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck, as well as regional staging through detection techniques and biopsies of sentinel lymph nodes of the head and neck.

To show how locating, dissecting and removing periparotid and intraparotid sentinel lymph nodes is possible, despite the inherent difficulty due to their reduced size and the high risk of harming facial nerves.

Material and method

We have had the opportunity of treating 21 patients, diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck, in the Service of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery of the Infanta Cristina Hospital in Badajoz and the Cabueñes Hospital in Gijón. Unfortunately, 15 of the patients were sent to us with lymphatic metastasis of the head and neck following the resection of the primary tumor in another Service. Only six patients attended with untreated primary tumors and with no regional lymphatic metastasis. Of these, the diagnosis was corroborated histologically by means of an incisional biopsy, and an extension study was carried out by means of clinical examination, and thorough testing (hemogram and biochemistry including alkaline phosphatase and LDH)11 hepatic function tests, (GOT/GPT, Gamma GT) hepatic ultrasound and radiography of the thorax. If the clinical/radiologic test showed signs of metastasis, other radiological tests were carried out (cranium-thorax-abdomen CAT) or nuclear medicine (bone gammagraph). The neck was staged clinically and radiologically (TC, AJCC, UICC) in all cases.

All the patients with lymphatic metastasis of the head and neck underwent functional cervicofacial dissection or modified radical dissection, which included a parotidectomy in those cases when the periparotid and intraparotid lymph nodes were affected.

Head and neck staging was carried out in those patients that did not have regional metastasis by means of a selective lymphadenectomy of sentinel lymph nodes (SN) of the head and neck. These SN were identified by means of a preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and they were located intraoperatively by means of a surgical gamma probe (Scintiprobe Mr-100), Pol.hi.tech, Italy). As well as the removal of the SN, the primary cutaneous tumor was then resected and reconstructed with locoregional flaps (figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4). All the SN were studied by means of multiple sectioning and staining with hematoxylin and eosin and by means of immunohistochemistry using the HMB 45, S 100 and Melan A antibodies.

The presence of metastasis in some SN led to a deferred therapeutic functional cervical dissection being necessary. In patients with multiple metastatic adenopathy or with extracapsular invasion additional radiotherapy therapy (RT) was given. Treatment with interferon α-2b is indicated in patients with regional metastasis, an intermediate-deep Breslow thick- ness (<2 mm) and in ulcerated tumors (stages II-b and III). If distant metastasis appeared this was treated according to the Oncological Protocol.

Results

The current follow-up is between 15 and 36 months with an average of 29 months. Of the 15 patients with regional metastasis, eight had distant metastasis (six in the lungs, three in the liver and two in the brain) in an average time of 20 months (between 9 and 29 months). Six died as a result of their illness. Of the seven cases that did not have distant metastasis, two died due to consequences that were unrelated to their illness, with the remaining five currently being disease free.

Of the six patients treated for primary tumors that did not have cervical metastasis, five cases corresponded to women and one to a man. The age range was between 28 and 79 years with 66 being the average age. Table 2 shows the most important clinical and histological characteristics of each case.

The preoperative lymphoscintigraphies (LSG) showed a total of 17 sentinel lymph nodes (SN), while during the surgery a total of 20 SN were resected. The three extra SN were periparotid SN of a female patient (Nº4) that only had two SN visible during the LSG and 5 SN during the surgery. We believe that the spatial resolution of the LSG did not allow identifying the presence of various SN in the same nodal level (Table 3).

In each patient there was an average of 3.3 SN with the range being between 1 and 5 SN. The interrelation of SN located during surgery on a cervical level, the histopathologic result and the type of treatment given appears in Table 2. Bilateral SN were obtained in one patient, of both with tumors located in the midline (nº 2 and nº6). In the remaining cases only ipsilateral SN were obtained. The levels where SN were more commonly found were the periparotid and high cervical areas. All the SN were radioactive or hot. Only in 2 patients methylene blue was injected before the surgical act. Of the 7 SN that were isolated in these cases, only two were dyed blue. In none of the 20 SN was the presence of metastases seen in the histopathologic study. Of these, 19 were found in reticular and dentritic cells (non-tumor cells) dyed after immunohistochemical staining.

No patient had cervical dissection as it was considered that regional staging had been carried out using the results of the histopathological study of the SN of the head and neck.

All patients are disease-free at the moment except one patient (case 4) who died 25 months after the treatment as a result of distant metastasis to the lungs. Curiously, she was the only patient to have complementary radiotherapy treatment.

Discussion

The considerable incidence of cutaneous melanoma (CM) in the head and neck, is attributed to many factors such as exposure to the sun and a distribution of melanocytes throughout the skin that is 2 to 3 times larger.4,5 Survival in patients depends on a multiple of interrelated prognostic factors that can be summed up by the appropriateness of early diagnosis and treatment. While those patients with early stages of the disease have cure rates of over 90%, the prognosis for patients with regional or distant metastasis is gloomy, with an average survival rate of 24 and 6 months respectively.2

The new classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), published officially in the year 2002, incorporates new prognostic factors that are more detailed, with the aim of carrying out a more precise stratification of patients (Table 1).6,7 Its complexity reflects the current debate and the multiple factors implied in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma.

The different clinical/morphologic types of CM do not carry an implicit prognostic value.5,12 Although the CM situated in the BANS region has not been demonstrated as more aggressive, the anatomic location influences the prognosis.12 The CM of the head and neck have a relatively worse prognosis as there is a high recurrence rate and mortality is high.3,5,12 The cause could lie in the skin being extremely fine in this area, which could lead to the risk of vascular and lymphatic spread being greater with a certain thickness. Within the area of the head and neck, a worse prognosis has been described for melanomas that originate in the scalp and cervical skin, while the prognosis is better for those originating in the external part of the ear and especially on the face.13,14 Unlike other tumors, with CM the size of the primary tumor does not have prognostic value.15 The T stage should be calculated initially by means of the histopathologic measurement of the thickness of the tumor, with a subclassification then being added that is called a or b according to there being ulceration or not.6 This carries a worse prognosis, as there is an independent risk factor for developing an advanced form of the disease.16 Clarks level should still be reflected as it still provides prognostic information of fine tumors (< 1 mm).6 Although a multitude of numbers have been proposed such as rupture point, tumor thickness, considered during decades as being the main factor determining prognosis, it presents a lineal correlation with survival and it should be treated as a continuous variable.17

Resection margins and the need for carrying out prophylactic lymphadenectomies of the head and neck are at the center of the debate on CM treatment. The current tendency is to consider 1 cm as sufficient, with margins above this being unnecessary especially in our region where aesthetic and functional sequelae are more evident.18 The histopathological stage of regional lymph nodes is the main factor determining prognosis with this neoplasm, above Breslows tumor thickness and any characteristic of the primary tumor,6,13 as a result of which the AJCC advises that staging should always be carried out.

Those patients with metastasis in lymph nodes of the head and neck require a regional lymphadenectomy. Parotid nodes represent the first drainage point in most tumors located in the ear, face and anterior part of the scalp. If there is parotid lymph node metastasis, cervical dissection should be carried out as well as the corresponding parotidectomy, as there is a high probability of there being metastasis in the cervical lymph nodes (between 47% and 58%).19

On the contrary, with patients with localized disease (N0) the advantages of prophylactic dissection on the global survival continues being one of the more controversial aspects. Prophylactic lymphadenctomy is aimed at eradicating micrometastatic lymph nodes in order to increase the cure rate. While some studies report obtaining better results with preventive dissection,20 others do not achieve any advantages that can be appreciated.13 Fisher,13 in a phenomenal retrospective work, analyzes survival and recurrence patterns in 1444 patients with melanoma of the head and neck according to the neck dissections carried out prophylactically, therapeutically or differed until the appearance of metastasis. In the multivariate analysis he observed better survival in patients that had only received a lymphadenectomy following the appearance of metastasis (6.14 years on average, 56% were alive 5 years later), compared with those that had this prophylactically with nodal metastasis being avoided (2.12 years on average, 24% were alive 5 years later). These results suggest that a prophylactic lymphadenectomy does not produce a positive impact with regard to the survival of patients with hidden metastasis; differing dissection until clinically evident metastasis appears to be the best therapeutic option. The cause of this is not clear: possibly and theoretically, microscopic tumor volumes that have been present over a long period of time within the lymphatic system could stimulate an immune response by activating T cells, in the same way as vaccines.

The histopathologic study of prophylactic lymphadenectomies carried out in patients with CM of the head and neck showed that only between 4-23% (12% on average) had ganglionic metastasis.3,20,21 This implies that 77-96% of patients with N0 necks had unnecessary treatment. As a result of all this, when there is no preoperative clinical/radiological evidence of metastasis in the head and neck (clinical stages T2, T3 and T4, N0, M0), the AJJCC and the UICC are imperative about recommending regional lymph node staging by means of selective lymphadenectomies of sentinel lymph nodes (SN).7,10,11

The detection technique and biopsy of SN provides data that is so determinant that it has become the treatment of choice for carrying out regional lymph node staging (N), with these results being incorporated into the latest version of the classification system of the CM.8,21,22 The size of the lymph nodes is therefore replaced by the number of lymph nodes that are affected and the tumor "weight" of these (microscopically versus macroscopically). These two pieces of data are the most important in survival prediction for patients with nodal disease, with two types of classification offered that are clinical and histopathologic.6 Survival decreases as the number of affected lymph nodes increases and/or the evidence is macroscopic.

Recent data of multiple works confirms the efficiency of the technique with high sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic reliability for detecting subclinical metastasis with very low rates of false negatives and complications.10,21 Our results show that this technique is predictable and reliable for these tumors, and that very important data is provided for evaluating prognosis and the need for adjuvant therapy.

Selective lymphadenectomies of SN have obvious advantages over classical dissections. On the one hand carrying out a more exhaustive study of lymph nodes (multiple selection and immunohistochemistry), allows identifying the presence of microscopic lymph node metastasis and carrying out neck staging that is more precise6-11 (the standard histopathologic study, a section of every lymph node half, carry a high risk of not identifying microscopic metastasis).23

This also avoids morbidity due to the unnecessary dissection of lymph nodes of the head and neck, financial cost is reduced and patients have better quality of life.8,10,24 Although patients with metastasis in a SN require therapeutic lymphadenectomies in a second surgical act, this should be carried out in an earlier stage of the disease.

A lymphadenectomy of the head and neck is more delicate than in other regions.10 The drainage pathways of the head and neck, the multiplicity and ample distribution of the SN, together with its frequent intraparotid location with risk to the facial nerve, make carrying this out difficult.9-11,25 The high average of SN that we found in each patient (3.3 SN distributed across various lymphatic regions) shows the rich lymphatic drainage in this region, coinciding with that obtained by other authors (between 1.5 and 3.6 SN per patient with a mean of 2.67,23 2.8,25 and 3.6,10 distributed across various lymphatic regions 2.2).10 There is very important data that is surprising in that 55% of the SN were periparotid and intraparotid and in 66% of our patients there was a SN in this location. Other authors,10,25 obtain significant numbers although these are slightly lower (between 25%,25 and 44%,10 of patients), of note being their small size (between 3 and 4 mm), the difficulty in identifying them and the high risk of harming the facial nerve.

Multiple selection is essential in histologic studies in order to achieve reliable results, as in most patient the metastatic disease center is very small (measuring 4 mm or less).10 Although immunochemical techniques (TIM-45, S-100 and Melan A) can aid in identifying metastatic foci that have gone unnoticed in the hematoxylin and eosin analysis, today micrometastatic diagnosis requires identification by means of this last type of staining. Intraoperative biopsies by means of sectioning and freezing is not justifiable given the high incidence of false negatives (53%). The absence of metastasis in our SN may be a reflection of our limited samples and the early diagnosis of our patients. Larger samples show rates of 15%,29 and 21%,10 of SN with metastasis, which is the equivalent of 20% of patients.

The intraoperative mapping of SN by means a surgical gamma probe is so reliable, that many authors10 claim that a preoperative lymphoscintigraphy may soon be unnecessary for experienced teams, this also being our impression. In addition to the possible drawbacks in surgery and the risk of anaphylactic reactions, there is consensus in the literature10 as to the lack of effectiveness or vital staining for mapping SN.

Conclusion

The technique for the detection and biopsy of regional SN is considered the procedure of choice for carrying out regional ganglionic staging in cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Preoperative identification of aberrant lymphatic drainage patterns is improved and the efficiency and sensitivity of histopathologic studies, as the lymph nodes of the head and neck with a greater probability of having subclinical metastatic node foci (micrometastasis) are selected.

References

1. Lentsch EJ, Myers JN. Melanoma of the head and neck: Current concepts in diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope 2001;111:1209-22. [ Links ]

2. Mackie RM, Bray CA, Hole DJ, Morris A, Nicolson M, Evans A, Doherty V, Vestey J. Incidence of and survival from malignant melanoma in Scotland: an epidemiological study. Lancet 2002;360:587-91. [ Links ]

3. White MJ, Polk HC. Therapy of primary cutaneous melanoma. Med Clin North Am 1998;135:1472-6. [ Links ]

4. Goldsmith HS. Melanoma: an overview. Cancer 1979;29:194-7. [ Links ]

5. ODonnell MJ, Whitaker DC. Clinical evaluation of tumors of the skin. En: Comprehensive Management of Head and Neck Tumors. Volumen 2. Thawley SE, Panje WR, Batsakis JG, Lindberg RD Eds. W.B. Saunders Company. Philadelphia. 1999;1222-46. [ Links ]

6. Kim CJ, Reintgen DS, Balch CM. The new melanoma staging system. Cancer Control 2002;9(1):9-15. [ Links ]

7. Balch CM, Mihm MC. Reply to the article «The AJCC staging proposal for cutaneous melanoma: comments by the EORTC Melanoma Group», by D.J. Ruiter y cols. (Ann Oncol 2001; 12: 9-11). Ann Oncol 2002;13:175-6. [ Links ]

8. Belhocine T, Pierard G, Labrassinne M, Lahaye T, Rigo P. Staging of regional nodes in AJCC stage I and II melanoma: 18FDG PET imaging versus sentinel node detection. The Oncologist 2002;7:271-8. [ Links ]

9. Lentsh EJ, McMasters KM. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma of the head and neck. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2003;3:673-83. [ Links ]

10. Eicher SA, Clayman GL, Myers JN, Gillenwater AM. A prospective study of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for head and neck cutaneous melanoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002;128:241-6. [ Links ]

11. Morris KT, Stevens JS, pommier RF, Fletcher WS, Vetto JT. Usefulness of preoperative lymphoscintigraphy for the identification of sentinel lymph nodes in melanoma. Am J Surg 2001;181:423-6. [ Links ]

12. Brown M. Staging and prognosis of melanoma. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 1997;16:113-21. [ Links ]

13. Fisher SR. Elective, therapeutic, and delayed lymph node dissection for malignant melanoma of the head and neck: analysis of 1444 patients from 1970 to 1988. Laryngoscope 2002;112:99-110. [ Links ]

14. Urist MM, Balch CM, Soong SJ, y cols. Head and neck melanomas in 536 clinical stage I patients: a prognostic factors analysis and results of surgical treatment. Ann Surg 1984;200:769-75. [ Links ]

15. Karakousis CP, Emrich LJ, Rao U. Tumor thickness and prognosis in clinical stage I malignat melanoma. Cancer 1989;64:1432-6. [ Links ]

16. McGovern VJ, Shaw HM, Milton GW, y cols. Ulceration and prognosis in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Histopatology 1982;6:399-407. [ Links ]

17. Buttner P, Garbe C, Bertz J, y cols. Primary cutaneous melanoma : optimized cutoff points of tumor thickness and importance of Clarks level for prognostic classification. Cancer 1995;75:2499-506. [ Links ]

18. Versoni U, Cascinelli N. Narrow escisión (1 cm margin): a safe procedure for thin cutaneous melanoma. Arch Surg 1991;126:438-41. [ Links ]

19. OBrien CJ, Mcneil EB, McMahon JD, Pathak I, Lauer CS. Incidence of cervical node involvement in metastatic cutaneous malignancy involving the parotid gland. Head Neck 2001;23:744-8. [ Links ]

20. Renner GJ, Gaston DA, Clark DP. Controversy in the management of tumors of the skin. En: Comprehensive Management of Head and Neck Tumors. Volumen 2. Thawley SE, Panje WR, Batsakis JG, Lindberg RD Eds. W.B. Saunders Company. Philadelphia 1999;1309- 19. [ Links ]

21. Mariani G, Erba P, Manca G, y cols. Radioguided sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with malignant cutaneous melanoma: the nuclear medicine contribution. J Surg Oncol 2004;85:141-51. [ Links ]

22. Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, y cols. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3635-48. [ Links ]

23. Davison SP, Clifton MS, Kauffman L, Minasian L. Sentinel node biopsy for the detection of the head and neck melanoma. A review. Ann Plastic Surg 2001;47: 206-11. [ Links ]

24. Pathak I, OBrien CJ, Petersen-Schaeffer K, y cols. Do nodal metastases from cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck follow a clinically predictable pattern? Head Neck 2001;23:785-90. [ Links ]

25. Chao C, Wong SL, Edwards MJ, y cols. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for head and neck melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol 2003;10:21-6. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en