Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versão On-line ISSN 2173-9161versão impressa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.28 no.5 Madrid Set./Out. 2006

Implant-supported rehabilitation using the fibula free flap

Rehabilitación implantosoportada en el colgajo libre de peroné

C. Navarro Cuéllar1, S. Ochandiano Caicoya2, F. Riba Garcia1, F.J. Lopez de

Atalaya2,

J. Acero Sanz2, M. Cuesta Gil2, C. Navarro Vila3

1 Médico Residente.

2 Médico Adjunto.

3 Jefe de Servicio. Catedrático de Cirugía

Maxilofacial. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Servicio de Cirugía Oral

y Maxilofacial.

Hospital General Universitario Gregorio

Marañón. Madrid, España.

Premio "Lorenzo Castillo" 2003

Dirección para correspondencia

ABSTRACT

Free

fibula flap has proved to be one of the most versatile for oromandibular

reconstruction due to the available length of bone and the possibility of

incorporating a long skin paddle to cover intraoral soft tissues.

The use of osseointegrated dental

implants is an important technique for the oral rehabilitation of these patients.

Osseointegrated implants provide the most rigid prosthetic stabilization

available to withstand masticatory forces.These implants can be placed

immediately or in a second time procedure.In our case, implantation in the

fibula free flap is done after 6-12 months because of the large amount of

osteosynthesis material required forthe fixation of the flap. Four or six months

later, when osseointegration has taken place, the implants are loaded with a

dental rehabilitation. We analize 12 cases of mandibular reconstruction with

fibula free flap and their aesthetic and functional rehabilitation with

osseointegrated implants with a 2 year follow up Fifty-six dental implants were

placed developing all of them but one a correct osseointegration. All these

patients recovered masticatory function and underwent a considerable improvement

in labial competence, salival continence, speech articulation and facial harmony.

Key words: Mandibular reconstruction; Free fibula flap; Osseointegrated implants.

RESUMEN

El

colgajo de peroné ha demostrado ser el más versatil para la reconstrucción

oromandibular, gracias a la gran longitud ósea que podemos utilizar y a la

posibilidad de incorporar una amplia paleta cutánea para cobertura de tejidos

blandos intraorales.

El uso de implantes dentales osteointegrados

proporciona un importante método terapéutico para la rehabilitación oral de

estos pacientes. Los implantes osteointegrados proporcionan la forma más

rígida de estabilización protésica para soportar las fuerzas masticatorias.

Estos implantes pueden ser insertados de forma inmediata o diferida. A la hora

de utilizar el colgajo libre de peroné realizamos la implantología de forma

diferida a los 6-12 meses debido a la gran cantidad de material de

osteosíntesis necesaria para la fijación del colgajo. Cuatro o seis meses

después, cuando el proceso de osteointegración ha ocurrido, los implantes son

cargados con una rehabilitación dental.

Analizamos 12 casos de reconstrucción

mandibular con colgajo libre de peroné y su rehabilitación estética y

funcional con implantes osteointegrados y un seguimiento mínimo de 2 años. Se

han colocado un total de 56 implantes, presentando todos ellos excepto uno, una

correcta osteointegración. Todos estos pacientes han recuperado la función

masticatoria, y mejorado de forma considerable la competencia labial, la

continencia salival, la pronunciación y la armonía facial.

Palabras clave: Reconstrucción mandibular; Colgajo libre de peroné; Implantes osteointegrados.

Introduction

Mandibular reconstruction, within the field of head and neck reconstruction, has been a very debated subject that has been studied over the years, and especially over the last fifty.1 The removal of extensive tumor lesions often leads to considerable bone and soft tissue defects, with the resulting aesthetic and functional sequelae.2

From the aesthetic point of view, a retraction in the lower third of the face is produced, especially if the mandibulectomy includes the symphyseal and parasymphyseal area. In these cases, considerable ptosis of the lower lip will arise.

When the resection affects the mandibular body, there is clear facial asymmetry as the affected area sinks. This asymmetry is more noticeable if, in the resection, the condyle is included.

From a functional point of view, the most important sequelae are: incompetence of the lower lip, salivary continence, severe difficulty in mastication and swallowing, and difficulty in articulation.

On the one hand the non-reconstructed part of the mandible suffers retraction and deviation towards the resection side. On the other, the previous vertical movements are replaced by oblique or diagonal movements that are controlled by just one temporomandibular joint. The tongue is limited with regard to mobility and strength and proprioceptive sensitivity disorders leads to a lack of coordination in the movements of the mandible.3

The fibula flap was first described by Taylor4 in 1975. Gilbert, in 1979, introduced a lateral approach that was much simpler, which is the one that is used today. Ueba and Fukjikaua5 started to use this flap for treating congenital cubitus pseudoarthritis in 1983. In 1988 Hidalgo6 began using this flap for reconstructing the mandible. For approximately the last ten years this is the flap used by Navarro Vila et cols.7-10 as one of the principal reconstruction techniques for the mandible.

The fibula free flap offers great advantages in mandibular reconstruction. One of the most important is the length of bone that is provided, as a minimum of 4 cm and a maximum of 25 cm is supplied.11

The size of the skin island that is to be incorporated depends principally on the size of the resection and the size of the flap that is needed for reconstructing the oromandibular defect. The skin is irrigated by septocutaneous and musculocutaneous branches of the peroneal artery. The most important study on vascularization of the skin was carried out by Wei12. One of their conclusions was that there tended to be between 4 and 7 cutaneous branches, with the more numerous musculocutaneous vessels being at a proximal level and the septocutaneous branches at a distal level. It is because of this that the pedicle has a fusiform design and it is centered in the intermuscular septum where the middle and distal third meet.

Moreover, Hayden and OLeary13 described the sensory re-innervation of a skin patch by means of anastomosis of the lateral sural cutaneous nerve with an appropriate receptor nerve. Nevertheless, we have not carried this out as a routine procedure as the sensitive reinnervation of the flap does not require anastomosis of the nerves in a large number of cases.

The implant-supported prosthetic dental rehabilitation offers these patients a definitive solution for restoring masticatory function and for improving other sequelae. Branemark y Lindstrom14 used implants with free bone grafts. Riediger15 was the first to place them in an iliac crest flap, Navarro Vila7 in the trapezius osseomyocutaneous flap and Urken16 was the first in placing them immediately, at the time of the reconstruction.

Material y methods

In this paper 12 patients are presented who underwent mandibular resection and reconstruction with the fibula free flap. They were fitted with osseointegrated implants by means of delayed placement at 6-12 months after the reconstruction (Table 1).

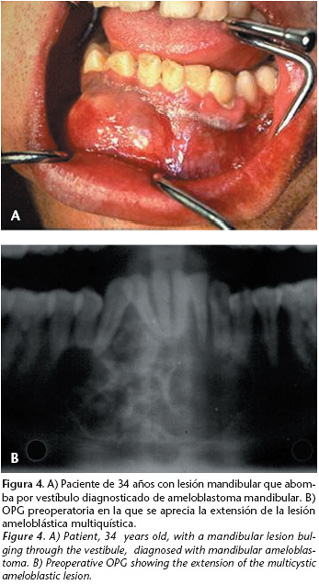

The sex distribution was 10 males (88%) and two females (12%), between the ages of 21 and 73. The mean age was 50.7 years. Within our series, the most common reason was malignant tumors in seven out of the 12 cases (58%). In another two patients the cause was mandibular ameloblastoma, there was one patient with osteoradionecrosis and we had one case of oncological sequelae that was operated on by another center and sent to ours for reconstruction. Lastly, and as regards etiology, we reconstructed one case of complete right-sided hemimandibular agenesis. With regard to when reconstruction of the oncological cases not treated previously took place, this was carried out in all cases immediately after surgical resection.

Titanium miniplates were used in all patients (100% of cases) for fixing the fibula free flap into the remaining mandible. In none of the patients did we carry out intermaxillary fixation in order to avoid any movements that could damage the vascular pedicle.

Seven of the 11 oncological patients (63%) received radiotherapy, two of them preoperatively and five postoperatively.

All patients were fitted with osteointegrated titanium implants that were covered with hydroxyapatite. In all cases (100%) the implantology was carried out as a delayed procedure between six and 12 months after the mandibular reconstruction. A total of 56 implants were placed into fibula flaps. Similarly, for those edentulous maxilla patients and/or mandible remnant patients, implants were also placed in the same surgical act in order to achieve a more stable dental prosthetic solution. The size of the implants were, in most cases, 10 mm in length and 4mm in width although we were able to insert five implants of 13 mm and three of 15mm in the case of mandibular agenesis after previous bone distraction. For the initial placement, a second intervention was necessary in which the large amount of osteosynthesis material that was necessary for fixing the flap was removed. All patients were given widespectrum antibiotic treatment for 7-10 days. The implants required a period of osseointegration that was 4-6 months for patients not given radiotherapy, and 6-9 months for irradiated patients.

The second surgical phase for exposing the implants was carried out using local anesthesia, except in one case that required general anesthesia due to the limited oral opening of the patient. Once the closure screws had been replaced with transmucosal healing abutments, there was a wait of 10 to 15 days before impressions were taken.

Results

Of the 56 implants that were placed into fibula flaps, initial osseointegration was 98.2% and there was only one failure following prosthetic loading. There was a minimum two-year followup, and the success rate was 94.6% (three lost implants). Preoperative radiotherapy did not have a negative effect on the implants that was statistically significant. Postoperative radiotherapy led to minimal peri-implant bone loss in two patients. Nevertheless, osseointegration of these implants was correct and there were no problems with later rehabilitation. Of the 12 patients, eight were fitted with implant-supported fixed prostheses, and four with removable implant-retained prostheses. The fixed prosthesis requires a minimum of six implants, while three may be sufficient for the removable one.

With regard to complications, we registered symptoms of epidermolysis of the flap and dehiscence of an intraoral wound, both responded satisfactorily with local treatment. In two of the cases the defects had been reconstructed previously with iliac crest flaps, one of which had been removed because of thrombosis of the pedicle and osteomyelitis of the flap. The other was removed because of carcinoma recurrence. One of the patients in our study had various complications that included partial necrosis of the lateral fibular muscle and an orocutaneous fistula; both were resolved with conservative treatment. The bone flap suffered a right-sided parasymphyseal fracture that required surgical reintervention and reduction and fixation with two titanium miniplates.

From the aesthetic point of view, all patients were satisfied and they all had a correct facial contour. As a result of the prosthetic rehabilitation by means of osteointegrated implants, all patients except one were able to eat normal food. Proprioceptive sensitivity in approximately half of the cases was restored, and in many of the cases acceptable lingual mobility was achieved. All the osteointegrated implants were used except four, because there was no occlusion.

As a result of the mandibular reconstruction carried out and the functional rehabilitation with osteointegrated implants, there have been considerable improvements for the patients with problems in the areas of mastication, swallowing, salivation and labial competence, and spectacular improvements have been achieved with regard to aesthetic facial harmony.

Discussion

Reconstructive surgery has experienced great advances over the last 20-30 years. Until recently mandibular reconstruction was based on pedicled bone flaps, reconstruction plates, bone grafts and alloplastic bands of bone particles. As a result of the development of microsurgical techniques and osteointegrated implants, integral treatment of oncological patients has improved considerably.17

Oromandibular rehabilitation is an arduous task that requires complex reconstruction that is individualized for each defect and adapted to the needs of the patient. Individualizing each case is fundamental, as is studying each patient in detail in order to select the right microsurgical flap for the reconstruction.

The microsurgical fibula flap has a series of advantages with regard to other flaps in oromandibular reconstruction:

• Usable bone of great length (up to 25 cm).

• Two different surgical teams can work in the same intervention.

• The considerable periosteal vascularization that allows the possibility of carrying out multiple osteotomies for remodeling.18

• Sensate reinervation of the skin island.13

• Minimum morbidity at the donor site.

Nevertheless, the fibula flap also has a series of disadvantages, of note:

• Multiple osteotomies for remodeling are required together with large amounts of osteosynthesis material.

• The bone height obtained is poor, and posterior functional rehabilitation with the osteointegrated implants is hampered. Moscoso.20 claimed that in approximately 15% of males and somewhat more in females, implants cannot be placed because the fibula lacks height.

• The placement of implants has to be done in a second stage due to the surgery required for such a large amount of osteosynthesis material. 21

• Bone has little height for segmental defects, and there is a difference in height between the flap and the remaining mandible and an unfavorable crown-prosthetic-implant relationship. This can be solved successfully by means of secondary vertical distraction of either the fibula22 or by a "double-barrel" fibular graft as described by Jones.23

• The irrigation of the cutaneous component is very inconsistent, due to the large amount of anatomic variants. This is the main problem with this flap. In order to overcome these inconveniences we follow a set of measures that are:- The patch should be centered on the two distal thirds of the leg where there are more perforating branches of the peroneal artery.

- The skin paddle should be as long as possible so that as many perforating vessels as possible are incorporated.

- The patch of skin should be approached anteriorly until the septum is reached and the muscular wedge formed by the soleus and long flexor muscle of the big toe should be included so that musculocutaneous perforating vessels are incorporated.• Although angiographic studies are still the object of discussion, we used them systematically to demonstrate, on the one hand that the peroneal artery was free of disease, and on the other to confirm that it did not have dominant circulation in the leg, as in this case the use of this flap would be contraindicated.24

• The patient is required to remain immobile after the operation for five to seven days, and for up to three weeks if a dermoepidermal graft is used.

Currently the indications for using a fibula free flap are well established:

• Mandibular reconstruction in conjunction with considerable intraoral soft tissue defects.

• Reconstruction of symphyseal mandibular defects, either near total or total that may be over 14 cm.

• Reconstruction of the branch and condyle as the bone can be moved to the glenoid cavity with minimal dissection and with no damage to the facial nerve.

• Mandibular reconstruction during childhood. Genden 25 established it as the flap of choice during childhood. Firstly, because it does not affect the distal and proximal growth centers, and growth of the leg is not affected. And secondly, because the new mandible grows at the same rhythm as the remaining mandible. Omokawa26 indicated that patients under the age of 8 should carryout a synostosis of the ankle in order to avoid the development of valgus deformity.

The incorporation of osteointegrated implantology in the oromandibular rehabilitation of oncological head and neck patients has improved aesthetic and functional results spectacularly. 9

Branemark and Lindstrom14 used free bone grafts. Riediger15 was the first in placing them into iliac crest flaps and Navarro Vila et cols.7 into the trapezius osseomyocutaneous flap.

For perfect functional rehabilitation of patients we should resolve the problems that affect mastication, swallowing, salivation and the aesthetic results should be improved. In order to achieve this, it is necessary for the dental surfaces of the jaw fit together perfectly. In addition to this, proper vascularization of the microsurgical flaps favors the incorporation of the implants and the restoration of masticatory function for patients.27,28,30

As a result of mandibular reconstruction and radiotherapy, changes take place in the orofacial muscles. There are bone irregularities, vestibular loss, changes in sensitivity, xerostomia and mucosal atrophy that contraindicates the use of conventional prostheses as irritation, ulceration and bone exposure may occur29 that can sometimes lead to osteoradionecrosis.

As a result of the prosthetic stability provided by the osteointegrated implants, refining the flap is not necessary, nor is carrying out secondary vestibuloplasties,29 which in many cases facilitates the therapeutic procedure.

There are two minimum conditions that are required for placing osteointegrated implants:

- minimum bone height of 10 mm20

- bone width of approximately 5.3 mm so that an implant with a width of 3.3 mm can be placed, while leaving 1 mm of alveolar bone in each cortical layer.31

It has been demonstrated statistically that microvascularized bone flaps are better at accepting implants than normal alveolar bone due to their greater vascularization and, as a result, the adverse effect of radiotherapy is minimal. The iliac crest flap has the best vascular supply followed by the fibula and the scapula.3

During the follow-up of our 12 patients, we were able to observe that in nine of the patients there was no periimplant bone loss, which is considered normal for implants into non-transplanted bone, after prosthetic loading (0.1 mm/year).32

Placing the implants can be carried out immediately (in the same surgical act)33 or this can be delayed until six months after the surgery. Our criteria is to carry out, whenever possible, the implantology immediately as this has a series of advantages:

• Faster functional rehabilitation.9

• Access to the new mandible is simpler than in delayed loading.

• Retraction of soft tissues and lower lip is avoided.

• For those patients that are to undergo postoperative radiotherapy, this is reduced by a year.

Nevertheless, there is considerable controversy with regard to when implants should be placed in patients that are going to undergo radiotherapy. Some authors such as Kroll34 and Kuriloff32 recommend that they are not placed immediately and for there to be a delay of approximately 12 months. Sanger27 like ourselves does not contraindicate this.9 On the contrary, we believe that this is another factor to recommend the immediate placement of the implants. On the one hand, if more than 4-6 weeks evolve between the reconstruction and the beginning of the radiotherapy, there are 4-6 additional weeks until the start of the adverse radiotherapy effects on the bone. This provides a window period of 12 weeks. During this period in which radiotherapy has not been affecting bone vascularization, the osteophylic and osteoconductive phases of osseointegration have taken place.17,35 Furthermore, if delayed implant placement is carried out, the new mandible has poorer vascularization and peri-implant bone resorption can increase, which creates more difficulties and more possibilities of complications with regard to the correct rehabilitation of the patient.

However, with the fibula flap, delayed implantology was carried out six months after the reconstruction of non-irradiated patients, and 12 months later in patients that underwent radiotherapy. The motives behind this decision are based on the fibula bone lacking height and that multiple remodeling osteotomies are carried out. The large amount of osteosynthesis material will, in most cases, prevent the correct number of implants to be placed in the correct position.

When deciding if rehabilitation should include a fixed prosthesis or a removable prosthesis, a series of factors should be analyzed:

• Number and position of implants.

• Occlusal space.

• Antagonist arcade.

• TMJ function.

• Labial or lingual hypoesthesia.

• Patients attitude to prosthetic hygiene.

The fixed prosthesis requires a larger number of implants, occlusal adjustment is more complex and maintaining hygiene is more difficult. Similarly, treatment is more costly, but it provides greater satisfaction for the patient in comparison with the removable prosthesis. This requires a lower number of implants for rehabilitation, occlusal adjustment is simpler, maintaining hygiene is easier and the cost is lower.

Conclusions

To conclude this paper we should say that, in spite of healing being our priority and objective, the development of microsurgical techniques and osteointegrated implantology has made ostensive improvements with regard to the integral treatment of oncological patients. Therefore, we would like to stress the real possibility that we have of offering mandibulectomized patients that have been reconstructed with a fibula flap, dental rehabilitation with an implant-supported prosthesis and/or implant-retained prosthesis that will improve facial harmony and quality of life. The satisfaction index with this type of treatment is very high, given that what most patients demand after surgery and radiotherapy, is the possibility of having teeth again and eating normally.

![]() Correspondencia:

Correspondencia:

Carlos Navarro Cuéllar

C/ María Molina 60, 7ºA

28006 Madrid, España

e-mail: cnavarrocuellar@mixmail.com

Recibido: 14.07.2003

Aceptado: 06.10.2006

References

1. Urken ML, Weinverg H, Buchvinder D, Moscoso JF, Lauson W. Microvascular free flaps in head and neck reconstruction. Report of 200 cases and review of complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;120:633-40. [ Links ]

2. Komisar A. Mandibular reconstruction: History and review of the literature. En: Komisar A. Mandibular Reconstruction. Ed Thieme, New York, 1997:1-9. [ Links ]

3. Cuesta GM. Implantes osteointegrados inmediatos en reconstrucción mandibular microvascular. Rev Esp Cirug Oral Maxilofac 1996;18,4:200-13. [ Links ]

4. Taylor GI, Miller DH, Ham FJ. The free vascularized bone graft. A clinical extension of microvascular techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg 1975;55:533-44. [ Links ]

5. Ueba Y, Fujikaua S. Vascularized fibula graft to neurofibromatosis of the ulna. A 9 years follow up. Orthop Surg Traumatol 1983;26:595-600. [ Links ]

6. Hidalgo D. Fibula free flap: a new method of mandibule reconstruction. Plast Reconst Surg 1989;84. [ Links ]

7. Navarro Vila C, Borja Morant A, Cuesta M, López de Atalaya FJ, Salmerón JI, Barrios JM. Aesthetic and functional reconstruction with the trapezious óseomyocutaneous flap and dental implants in oral cavity cancer patients. J Craniomaxilofac Surg 1996;24:322-9. [ Links ]

8. Navarro Vila C, López de Atalaya FJ, Cuesta Gil M, Verdaguer JJ. Nuestra experiencia reconstructiva en cáncer avanzado de cabeza y cuello. Rev Esp Cirug Oral Maxilof 1995;17:1-17. [ Links ]

9. Cuesta Gil M, Ochandiano S, Barrios JM, Navarro Vila C. Rehabilitación oral con implantes osteointegrados en pacientes oncológicos. Rev Esp Cirug Oral Maxilof 2001;23:171-82. [ Links ]

10. López de Atalaya FJ. Utilización de los colgajos microquirúrgicos en cirugía maxilofacial. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad Complutense. Madrid, 1996. [ Links ]

11. Hidalgo DA. Fibula free flap: a new method of mandibule reconstruction. Plast Reconst Surg 1989;84:71-79. [ Links ]

12. Wei FC, Chen HCh, Chuang ChCh, Noordhoff MS. Fibular Osteoseptocutaneus Flap: Anatomic Study and clinical Application. Plast reconst Surg 1986;78:191-9. [ Links ]

13. Hayden R, OLeary M. A neurosensualy fibula flap. Anatomical description and clinical applications. 94 th Annual Meeting of the American. Laryngol Rhynolog Otolog Society Meeting. Hawaii 1991. [ Links ]

14. Branemark PI, Lindstrom J, Hallen O, Breine Ujeppson PH, Ohman A. Reconstruction of the defective mandible. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg.1975;9:116-28. [ Links ]

15. Riediger, D. Restoration of masticatory function by microsurgically revascularized iliac crest bone grafts using endosseous implants. Plast Reconst Surg. 1988; 81:861-6. [ Links ]

16. Urken ML, Buchbinder D, Weinberg H. Primary placement of osseointegrated implants in microvascular mandibular reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1989;101:56-73 [ Links ]

17. Urken Ml, Weinberg H, Vickery C, Butchvinder D, Lauson W, Biller HG. Oromandibular reconstruction using microvascular composite free flaps. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:733-44. [ Links ]

18. Urken ML. Composite Free Flaps in oromandibular Reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:724-32. [ Links ]

19. Urken ML, Weinberg MD, Vickery C, Aviv JE, Buchbinder D, Lawswon W, Biller HF. The combined sensate radial forearm and iliac free flaps for reconstruction of significant glossectomy-mandibulectomy defects. Laryngoscope 1922;102: 543-58. [ Links ]

20. Moscoso JF, Keller J, Genden E, Weimberg H, Biller, HF; Buchbinder D, Urken ML. Vascularized bone flaps in oromandibular reconstruction. A comparative anatomic study of bone stock from various donor sites to asses suitability for enosseous dental implants. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;120:36-43. [ Links ]

21. Zlotolow IM, Huryn JM, Piro JD, Lenchewski E, Hidalgo DA. Osseointegrated implants and functional prosthetic rehabilitatio in microvascular fibula free flap reconstructed mandibles. Am J Surg 1992;164:677-81. [ Links ]

22. Marx RE, Ehler WJ, Peleg M. Mandibular and facial reconstruction. Bone 1996;19:59s-82s. [ Links ]

23. Jones N, Swartz W, Mears D, Jupiter J, Grossman A. The "double- barrel" free vascularized fibular bone graft. Plast Reconst Surg 1988;81:378. [ Links ]

24. Hidalgo DA, Rekow A .A review of 60 consecutive fibula free flap mandible reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;96:585-96. [ Links ]

25. Genden E, Buchbinder D, Chaplin JM, Urken ML. Reconstruction of the pediatric maxillae and mandible. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;126:293-300. [ Links ]

26. Okokawa S, Tamai S, Takayura Y, Yajima H, Kawanishi K. A long term study of the donor ankle after vascularized fibula grafts in children. Microsurgery 1996;17:162-6. [ Links ]

27. Sanger JR, Head MD, Matloub HS, Yousift NJ, Larson DL. Enhancement of rehabilitation by use of implantable adjuncts with vasculariced bone grafts for mandible rconstruction. Am J Surg 1988;156:243-7. [ Links ]

28. Urken ML, Buchbinder D, Weinberg H, Vickery C, Sheiner A, Parker R, Schaefer, J, Som P, Shapiro A, Lawson W, Biller HF. Functional evaluation following microvascular oromandibular reconstruction of the oral cancer patient: a comparative study of reconstructed and nonreconstructed patients. Laryngoscope 1991;101:935-50. [ Links ]

29. Lukash F, Sach S. Functional mandibular reconstruction: Prevention of oral invalid. Plast Reconst Surg 1992;90:105-11. [ Links ]

30. Urken ML, Moscoso JF, Lawson W, Biller HF. A systematic aproach to functional reconstruction of the oral cavity following partial and total glossectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;120:589-601. [ Links ]

31. Frodel JL, Funk GF, Capper DT, Fridrich KL, Blumer JR, Haller JR, Hoffman HT. Osseointegrated implants: a comparative study of bne thickness in four vascularized bone flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993;92:449-55. [ Links ]

32. Kuriloff Db, Sullivan MJ. Mandibular Reconstruction Using Vascularized Bone Grafts. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991;24:1391-417. [ Links ]

33. Urken ML, Weinberg H, Vickery C, Buchbinder D, Lawson W, Biller HF. The internal oblique –lliac crest free flap in composite defects of the oral cavity involving bone, skin and mucosa. Laryngoscope 1991;101:257-70. [ Links ]

34. Kroll SS, Schuterman MA, Reece GP. Immediate vascularized bone reconstruction of anterior mandibular. [ Links ]

35. Marx R, Morales MJ. The use of implants in the reconstruction of oral cancer patients. Dent Clin North Am 1998;42:177-201. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em