Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versão On-line ISSN 2173-9161versão impressa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.28 no.5 Madrid Set./Out. 2006

What should the diagnosis and treatment be?

¿Cuál es su diagnóstico y tratamiento?

Ulcerative processes of the oral mucosa are frequently seen in the department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Often empirical treatment is started without having a diagnosis, which leads to complications. The diagnosis of the more common lesions is simple if certain rules regarding differential diagnoses are followed.

An example of this is presented by the case of a 38-year-old patient with previous knee surgery, non-smoker, who attended our center for an evaluation of lesions in the oral cavity that had been developing for seven months, and which had an ulcerated appearance (Figs. 1 and 2). The patient received multiple topical treatments but with no result. He was using anti-fungal mouthwashes and applying topical treatment to the lesions consisting of a corticoid/antibiotic cream.

Pemphigoid of the oral mucosa

Penfigoide de la mucosa oral

J. Mareque Bueno1, J.A. Hueto Madrid2,

S. Mareque Bueno3, J. González Lagunas2,

C. Bassas4,

G. Raspall Martín5, J. Palau Aymerich6

1. Médico Residente Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial.

2. Médico AdjuntoCirugía Oral y Maxilofacial.

3. Odontólogo.

4. Jefe Clínico.

5. Jefe de Servicio.

6. Anatomo-patológo.

Hospital Vall dHebrón, Barcelona, España.

Dirección para correspondencia

A hemogram, mycological culture swab, and a biopsy from the edge of one of the lesions were carried out. This was fixed in formalin and embedded, and a biopsy of fresh perilesional healthy mucosa was sent away for immunofluorescence.

Introduction

Pemphigoid is an autoimmune disease with autoantibodies against the basement membrane of the epithelium. It has also been called benign mucosal pemphigoid or Lortat- Jacob mucosynechiant dermatitis.1

Two forms of presentation can be distinguished: bullous and cicatricial pemphigoid. Bullous pemphigoid affects the skin and there are very few oral lesions. Cicatricial pemphigoid on the other hand is to be found principally in the mouth, eyes and other mucosal sites and there will be very few skin lesions. In many cases oral lesions are the first clinical signs, enabling early diagnosis.2

In both types antibodies appear against the antigens themselves, although probably the location and intensity of these autoaggressive reactions within the basal complex are different.3

The location of the blisters is the determinant clinical factor in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases. In pemphigoid, subepithelial blisters appear with a chronic course that give rise to cicatricial synechiae and functional sequelae. Depending on when we see the patient, we will observe a blister that is clearly situated in the mucosa, or an ulcerated area after detaching the superficial layer of the blister. Unlike pemphigus, where the blisters are intraepithelial, and observing well-formed blisters is usual, with pemphigoid clinically observing this epithelial detachment is possible, especially by the edge of the ulcers.4

Epidemiology

Both subtypes are observed during adulthood. The average age at onset is 60 and the age interval is 40 to 80. There is a 2:1 female predilection and they are relatively rare in children.5

Etiopathogeny

The reason for pemphigoid appearing is unknown. Various facts point to it having an autoimmune origin.6 The presence of circulating antibodies against the basement membrane has been demonstrated:

• Anti-laminin 5.

• Anti-laminin 5 and 6.

• Anti-168-kDa antigen.

• Anti-168-kDa antigen and BPAg2.

• Anti-both: laminin 5* and BPAg2.

Clinical symptoms

The first manifestation tends to be the appearance of one or various blistering lesions of the mucosa of the mouth or eyeball. Lesions may also appear+ on the skin, although this is less common (5-25%). Exceptionally the initial lesions will be found in pharyngeal, laryngeal or genital mucosal sites.

Within the oral cavity, these lesions tend to appear in the gingiva, palate and jugal mucosa; they are infrequently found on the tongue although the different series have different locations.

The lesions are smaller than in pemphigus. They are less likely to hemorrhage and the blisters are less likely to burst. The blister is the basic lesion that remains intact for 24-28 hours as a result of its thick roof. Once broken it will leave an erosion covered by a white friable membrane.

Those to be found in the gingiva manifest as desquamative gingivitis with glazed erythema of the free and attached gingiva. The epithelium covering the lesion may break away, leaving hemorrhaging connective areas. The clinical symptoms begin when the blister bursts and there is pain and a stinging sensation. It develops slowly and progressively, with exacerbations and remissions, and there are stationary periods that can vary from months to years.

Lesions in the mucosae of the eyeball are habitual. The cicatricial sequelae in this area can lead to symblepharon and even blindness. In the mucosal membranes of the larynx, pharynx or esophagus the scars can produce deglutition disorders.

Just as in psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis, the Koebner phenomenon may appear in cicatricial pemphigoid, or there may be an isomorphic reaction with the formation of new lesions in the areas suffering trauma. In this sense trauma through mastication could favor the accumulation of antibodies in the basement membrane of the oral mucosa.7

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is clinical and histopathological, and other blistering conditions should be ruled out.

The diagnostic biopsy technique should be very precise, and two samples should be taken: one in formalin to be embedded in paraffin and the other should be fresh for direct immunofluorescence. The specimen in paraffin should be taken from the edge of an active blister. The DIF specimen should be taken from healthy perilesional mucosa.

The histopathology (Fig. 3) shows the existence of a subepithelial blister, which is not exclusive to pemphigoid, as it is also present in the lesions of flat lichen planus, erythema multiform and epidermolysis bullosa. The blister divides all layers of epithelium above it and the subepithelial conjunctive tissue below it, and non-specific inflammatory infiltrates made up of eosinophils and plasma cells will be seen.8

With direct immunofluorescence (Fig. 4) a linear fixation pattern can be seen following the line of the basement membrane, with a high percentage of positivity for IgG and a lower percentage for C3, IgM and IgA. This linear deposit is not exclusive to this entity.

With indirect immunofluorescence the patients serum can be investigated and circulating Ig G can be identified using immunoblotting techniques and immunoprecipitation.

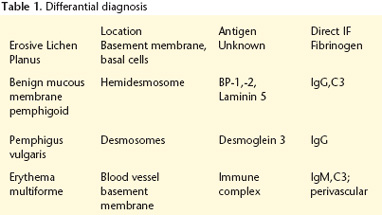

Differential diagnosis

Analyzing tissue specimen and carrying out immunofluorescence in order to differentiate benign mucosal penphigoid from other lesions with positive Nikolsky sign is necessary. The key factors are locating where the tissue separation takes place and specific immunoglobulin identification. With pemphigoid, lamina lucida will be found and it will be distinguished histologically by the basement membrane.9

The principal blistering entities that should be included in the differential diagnosis are shown in table I.

Lupus erythematosus should be highlighted as it has atrophic mucosal lesions together with clinical and analytical aspects associated with this process, biting lesion in patients with psychopathologic disorders; Behçets disease with typical genital sores; aphthae with a specific clinical course and oral lesions; neutropenic ulcers (a hemogram will show a disorder in the white cell count); leukemias (the hemogram will show a significant change in the white cells); immunodeficiencies (clinical background and analytical changes); desquamative gingivitis of different origins (lichen planus, vitamin deficiency, anemias, etc.).

Treatment

Intraoral lesions do not have a uniform response to treatment and on occasions they can appear resistant to therapy with topical as well as systemic corticosteroids. Local therapy: it is affirmed that the treatment of choice for lesions that have been located should be local corticoid treatment, and that for stubborn or extensive cases systemic treatment should be given. One of the possibilities is the application of creams with fluocinolone 0.05% in orabase, with 2 to 3 applications per day while there are lesions, and an improvement will be shown after 2 months of uninterrupted therapy. Another drug that can be applied topically is cyclosporine.10 This can be applied with a silicone cup.

Topical treatment with corticoids in these patients will result in some systemic absorption through the inflamed mucosal tissue, and a clinical and analytical follow-up should therefore be carried out in order to detect the appearance of any side effects.

Systemic therapy: if the response is not satisfactory, or if other areas of the organism are affected, especially the eyes, treatment with systemic corticoid therapy should be started with prednisone 40mg taken daily. When there is an improvement the amount of corticoids can be reduced, and small corticoid doses can be given on alternate days during prolonged periods. Other drugs that have been used are: dapsone, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, sulfamethoxypyridazine or tetracyclines.

Evolution y prognosis

Pemphigoid is a chronic autoimmune process that requires corticoid treatment for long periods of time. The oral lesions are easier to control than those in other locations. The appearance of fibrous bands of scar tissue in these oral lesions is more infrequent unlike what occurs in the eyes and other mucosal sites.

With proper treatment longer periods of remission are achieved and during this time treatment is not required. This occurs in approximately a third of cases. These patients should be followed for life, as once new lesions appear therapy should be re-established so that fibrous bands are avoided.

Early diagnosis avoids the appearance of complications and it permits establishing more accurate treatment. As oral lesions are the most common form of onset of the disease, the dentist and maxillofacial surgeon should include this possibility in the differential diagnosis of patients with ulcerated lesions of the oral mucosa.

![]() Correspondencia:

Correspondencia:

Joan Mareque Bueno

Hospital de la Vall dHebrón

Passeig de la Vall dHebrón, 119.

08006 Barcelona, España

Email: 36984@jmbomb.es

References

1. Chan LS, Ahmed R, Anhalt GJ, Bernauer W, Cooper KD, Elder MJ, y cols. The first international consensus on mucous membrane Pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:370-9. [ Links ]

2. Williams DM. Vesiculo bullous mucocutaneous disease: benign mucous membrane and bullous pemphigoid. J Oral Pathol Med 1990;19:16-23. [ Links ]

3. Castellanos Suarez JL. Enfermedades gingivales de origin immune. Med Oral 2002;7:271-83. [ Links ]

4. Bagan JV, Peñarrocha M, Milian MA. Penfigo vulgar y penfigoide benigno de la mucosa: estudio de sus manifestaciones orales en 24 casos. Av Odontoesestomatol 1993;9:387-92. [ Links ]

5. Zegarelli DJ, Sabbagh E. Relative incidence of intraoral pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrana pemphigoid and lichen planus. Ann Dent 1989;48:5-7 [ Links ]

6. Nayar M, Wojnarowska F, Venning V, Taylor CJ. Association of autoimmunity and cicatricial pemphigoid: is there an inmunogenetic basis? J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;25:1011-5. [ Links ]

7. Parisi E, Raghavendra S, Werth VP, Sollecito TP. Modification to the approach of the diagnosis of mucous membrane pemphigoid: a case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2003;95:182-6 [ Links ]

8. Bermejo A, Lopez P. Diagnóstico de las enfermedades vesiculares y ampollares de la mucosa bucal: desordenes de la cohesión intraepitelial y de la union epitelio- conectiva. Med Oral 1996;1:23-43. [ Links ]

9. Jorda E, Bagán JV, Silvestre FJ. Diagnóstico diferencial de las enfermedades ampollares de la mucosa oral: (II) Aspectos histologicos e inmunologicos. Estomodeo 1986;16:5-12. [ Links ]

10. Lamey PJ, Rees TD, Binnie WH, Rankin KV. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Treatment experience at two institutions. Oral surg 1992;74:50-3. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em