Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

versão On-line ISSN 2173-9161versão impressa ISSN 1130-0558

Rev Esp Cirug Oral y Maxilofac vol.29 no.3 Madrid Mai./Jun. 2007

ARTÍCULO CLÍNICO

Frontal sinus fracture treatment and complications

Tratamiento y complicaciones de las fracturas de seno frontal

S. Heredero Jung1, I. Zubillaga Rodríguez2, M. Castrillo Tambay1, G. Sánchez Aniceto2, J.J. Montalvo Moreno3

1 Médico Residente.

2 Médico Adjunto.

3 Jefe de Servicio.

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction. Frontal

sinus fractures are caused by high velocity impacts. Inappropriate treatment can

lead to serious complications, even many years after the trauma.

Objectives. To

evaluate epidemiological data and associated complications. To standardize the

treatment protocol.

Materials and methods. the clinical records of 95

patients with frontal sinus fractures treated between January 1990 and December

2004 at the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, "12 de Octubre"

Hospital (Madrid, Spain), were reviewed.

Results. The average age of

patients with frontal sinus fractures was 34 years. Most of them were male (78%)

and the most frequent mode of injury was motor vehicle accident. The commonest

frontal sinus fracture pattern was the outer table fracture. The complications

described were: cosmetic deformation, frontal sinusitis, frontal mucocele,

orbital cellulitis, intolerance of osteosynthesis material, meningitis and

persistent CSF leak.

Conclusions. Treatment of frontal sinus fractures

must be tailored for each individual patient. Its aim should be to reduce

associated complications, which may need a long-term follow-up to be detected.

Key words: Frontal sinus fractures; Obliteration; Cranialization; Subcranial approach.

RESUMEN

Introducción. Las

fracturas de seno frontal se producen como resultado de impactos de alta

energía. Un tratamiento inadecuado puede conducir a complicaciones serias

incluso muchos años después del traumatismo.

Objetivos. Evaluar

los datos epidemiológicos y revisar las complicaciones asociadas. Estandarizar

el protocolo de tratamiento.

Materiales y métodos. Se revisaron

95 pacientes diagnosticados de fracturas de seno frontal pertenecientes al

servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial del Hospital Universitario 12 de

Octubre de Madrid, entre enero de 1990 y diciembre de 2004.

Resultados. La edad media de los pacientes revisados es de 34 años. La mayoría son hombres

(78%) y la causa más frecuente del traumatismo, los accidentes de tráfico. El

patrón de fractura más común es el que afecta únicamente a la pared anterior

del seno frontal. Las complicaciones descritas son: deformidad estética

frontal, sinusitis frontal, mucocele frontal, celulitis fronto-orbitaria,

intolerancia al material de osteosíntesis, complicaciones infecciosas del SNC y

persistencia de fístula de líquido cefalorraquídeo.

Conclusiones.

El objetivo ha de estar encaminado a prevenir las complicaciones asociadas a los

pacientes con fracturas de seno frontal. Hay que individualizar el protocolo de

tratamiento en cada caso. Es recomendable un seguimiento a largo plazo para

identificar precozmente las posibles complicaciones.

Palabras clave: Fracturas de seno frontal; Obliteración; Cranealización; Abordaje subcraneal.

Introduction

Frontal sinus fractures are relatively rare and they represent 2 to 15% of all facial fractures1, 2 in the various series, and in our sector the incidence rate is 3.15%.3

The frontal sinuses, which are absent at birth, begin to develop as from the age of two, as a result of the outpouching of infundibular ethmoidal cells of the frontal recess. They cannot be observed radiologically until the age of eight, and they do not reach adult size until the age of 12. In 4% of people they are absent, in 5% they are unilateral and in 10% they are asymmetric. They drain towards the middle meatus through the so-called nasofrontal ducts that are located in the posteromedial region of the sinus floor. In as many as 85% of people these are not ducts as such, but simple drainage orifices.4

The mean volume of the adult frontal sinus is around 5 cm3. The posterior boundary of the frontal sinus meets the cribriform plate, the duramater and the frontal lobes. Its lower boundary meets the orbital roof. They are covered on the inside with sinus mucosa, and then with ethmoidal cells and the nasofrontal ducts. The mucosa has Breschets characteristic vascular pits, together with venous drainage points, which on the one hand can lead to intracranial dissemination of infections, and on the other to mucocele formation, if the mucosa covering them is not eliminated adequately.5

Nasofrontal fractures arise as a result of high-energy impacts, and they are frequently observed in polytraumatized patients and in other facial fractures. Numerous classifications have been proposed for frontal sinus fractures,5,6 but in general it can be said that evaluating any posterior table involvement, or of the nasofrontal duct, is fundamental.

Frontal sinus fracture treatment is controversial, as there is no single therapeutic algorithm. In addition, it is important to bear in mind that inadequate treatment of these fractures can lead to serious complications, principally of the infectious type, many years even after treatment.

The aim of this paper is to evaluate the epidemiological data and the clinico-radiological patterns corresponding to the analysis of frontal sinus fractures, as well as to review the associated complications, and the standardization of therapeutic management.

Material and method

In this study, 95 patients are reviewed who were diagnosed with fractures of the frontal sinus and who, in addition, required treatment on an in-patient basis by the department of Maxillofacial Surgery of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre in Madrid, between January 1990 and December 2004. 86 patients were included in the study. They all had complete clinical and radiological reports and they had been followed for a minimum of 6 months. The mean follow-up for all the series was 29 months. Periodic monitoring was carried out with CAT scans at 6, 12 and 24 months. The software program used for the statistics was the SPSS 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

With regard to the patients included in the study, there was a clear male predominance (78%). The sample shows an age distribution that is not strictly Gaussian (Fig. 1). Most of the individuals were between the ages of 20-30 and, in addition there was a group of patients in the 40-50 age range.

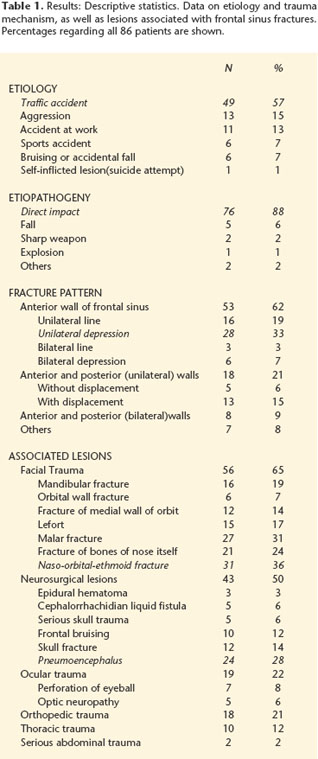

In table 1 the characteristics regarding etiology and trauma mechanism are described, as well as associated lesions on admittance. Traffic accidents were the most common cause of trauma in the study sample (57%). The mechanism producing the frontal sinus fractures was, in most patients, direct impact (88%).

The most common fracture pattern included only the anterior table of the frontal sinus, and this was observed in more than half the patients in the series. The more common fractures were those that specifically included unilateral depression. Moreover, most fractures with unilateral involvement of the anterior and posterior tables of the frontal sinus were displaced fractures. Lastly, a minority of the patients had fractures that affected the anterior and posterior tables of both frontal sinuses, caused by high-energy impacts, and these were frequently comminuted and associated with other facial fractures.

With regard to other lesions observed in patients with fractures of the frontal sinus, it is important to stress that 38 of these were in reality polytraumatized patients (44.2%). Therefore, the association with other types of trauma was common. The more common associated lesions included facial trauma, mainly fractures affecting the naso-orbitalethmoid complex, followed by orbito-malar fractures. In addition, the considerable association of neurosurgical lesions, observed in 50% of patients, and that can potentially be serious, should be taken into consideration. With the exception of craniocerebral trauma, the most common neurosurgical finding was pneumoencephalus (Fig. 2).

Forty-five patients required surgical treatment. A bicoronal incision was used in most cases (n = 34), although the approach was made through facial wounds in ten patients, and in one an upper blepharoplasty incision was made (in a 65 year-old female with a unilateral depressed fracture of the anterior table that was not comminuted). The fixation after reduction was carried out in most cases with low-profile titanium miniplates (1.3 and 1.0 mm), although resorbable plates were used in 4 patients of 7, 14, 27 and 29, all with unilateral depressed fractures of the anterior table of the frontal sinus that were not comminuted. In 7 patients either one sinus or both frontal sinuses were cranialized. In 5 cases one of the frontal sinuses was obliterated and in another 5 both were obliterated. The obliteration of the nasofrontal ducts and the frontal sinuses was carried out with autologous calvarial bone and a galeopericranial flap. Of all the patients reviewed, complications were registered in 14 patients or in 16.4%. Of these complications 38.46% were delayed, that is to say, they appeared after the first 6 months following the trauma. The most common complication observed was aesthetic deformity in the frontal region: 6 patients had slight sequelae, and in no case was posterior surgical correction required. With regard to local complications of an infectious type, two patients developed recurrent frontal sinusitis, two patients had frontal sinus mucocele and another patient developed fronto-orbital cellulitis that resolved spontaneously. In addition, a persistent fistula of cephalorrhaquidean liquid was observed in five patients, which resolved spontaneously in all of the patients except one, upon which a decision was made to cranialize the sinus, which solved the complication. Lastly, only in one patient was intolerance to osteosynthesis material, which required removal, observed.

Discussion

The epidemiological data observed coincide with other series previously published7, 8 with the patient prototype being a young male following a traffic accident. With regard to the fracture patterns found, it is important to mention that it is possible for a percentage of patients with isolated linear fractures of the anterior table of the frontal sinus to be lost, as admittance may not have been required. On the other hand, it is important to point out that the epidemiological association with other traumas that may be serious, implies the need for a multidisciplinary approach. In addition, lesions of a neurosurgical or ophthalmologic nature (compression of the optic nerve) can condition the need for urgent surgical treatment.

The objectives when planning treatment for a patient with a fracture of the frontal sinus, as proposed by Ionnides9 in 1993, should be:

1. Appropriate isolation of the anterior cranial fossa and repair of any CSF fistula.

2. Prevention of any possible complications of an infectious nature associated with the frontal sinus fracture.

3. Restoration of the previous aesthetic appearance before trauma.

For this, the treatment algorithm that we propose for fractures of the anterior table are set out in figure 3. The fractures of the anterior table that are linear, and that do not involve the nasofrontal duct, can be managed without surgical intervention. This was done with the slightly displaced fracture cases, where the expected aesthetic sequelae were minimal, and with patients that elected this attitude. When a lesion of the nasofrontal duct is suspected, obliterating the duct and sinus may be opted for, or an attempt may be made to leave it functioning by re-establishing patency. When obliterating the frontal sinuses, draining absolutely all the mucosa from these fragments is fundamental before reducing and fixing the bone fragments, duct and sinus. Drilling the sinus walls is recommended in order to eliminate the mucosa that may have remained in the Breschets vascular pits. Different materials have been proposed for obliteration with satisfactory results, autologous10 as well as synthetic. Among the autologous materials (fat, muscle, bone), calvarial bone chip (Fig. 4) has advantages as it is easy to obtain. It can be combined with other alloplastic material and it allows suitable follow- up by CAT scan, because it appears as bone density in the radiological image, which facilitates early detection of complications such as mucoceles, fistulas or abscesses. Some authors support preserving the function of the sinus, with the aim of minimizing the incidence of infectious complications. For this they resort to re-establishing patency of the nasofrontal duct by leaving in place, for a minimum period of 30 or 40 days, a drainage tube of plastic material.7 However, a 30% failure rate has been described with this technique as a result of stenosis of the nasofrontal duct.11 On the other hand, our experience was that both the patients with recurrent frontal sinusitis and those who developed mucoceles and whose initial surgery was less exhaustive, evolved favorably (Fig. 5) when, following complications, obliteration of the sinus was carried out. Moreover, complications of this type were not observed in patients whose initial treatment included obliteration.

If the fracture of the anterior table is displaced, and if damage to the duct is not suspected, it should be reduced and fixed, and bone grafts should be added if necessary. But if damage to the duct is suspected, the treatment should be completed with obliteration of the duct and sinus, or patency of the duct should be established.

When treating fractures of the anterior table of the frontal sinus, it is important to mention that the classical coronal approach may be substituted in certain cases by the endoscopic approach. The usefulness of this approach is currently recognized for treating fractures of the anterior table of the frontal sinus that are not comminuted12 as, in trained hands, surgery time may be reduced, as well the aggressiveness of the intervention, and the postoperative period may improve.

With regard to fractures that affect the posterior table, the therapeutic algorithm that we propose is set out in figure 6. In linear fractures with no CSF fistula, a conservative approach may be taken, and the fistula can be reevaluated for persistence after a few days. Otherwise surgical treatment can be chosen. When the fractures are displaced and comminuted, the sinus ideally should be cranialized in order to eliminate the fragments of the posterior table completely. Defects to the dura should be repaired (by means of direct suturing or duramater patch), the nasofrontal ducts should be obliterated and the anterior cranial fossa should be sealed with a galeopericranial flap (Fig. 7). This is in order to attempt to isolate the intracranial space so that the appearance of CSF liquid fistulas and the development of possible infectious complications are avoided. In the treatment of this type of fractures the subcranial approach can be used as described by Raveh.13 In this approach a more reduced frontal craniotomy is used on the frontal sinus than the classical bifrontal14 and subfrontal15 neurosurgical approaches that can be extended to include part of the orbital roofs, the lateral orbital walls, the glabella and the nasal bones. This craniotomy permits controlling the anterior cranial fossa and frontal duramater using a basal approach, without the need for retracting the frontal lobes. This leads to reduced cerebral edema and any neurosurgical lesions and associated craniofacial fractures can be treated promptly.

If the fractures of the posterior table are not comminuted, the fracture of the posterior table can be reduced and osteosynthesis carried out (Fig. 8), also proposed by Yavuzer.16 If the lesion is associated with the nasofrontal duct, obliteration of the sinus can also be carried out or cranialization. A similar approach can be taken with fractures with a CSF fistula that are not comminuted.

Conclusion

The principal objective when choosing the treatment best suited for a patient with a frontal sinus fracture has to be the prevention of associated short-term or long-term complications. For this, carrying out a precise clinical-radiological diagnosis is essential, as is a long-term follow-up, as there may be late complications.

The treatment algorithm proposed should be individualized in each case, and the particular characteristics of each patient should be taken into account, as should the experience of the surgeon.

The reduction and osteosynthesis of posterior table fractures, with additional obliteration of the nasofrontal duct if necessary, is presented as a valid alternative to cranialization.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Susana Heredero Jung

Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre

Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial

Avenida de Córdoba s/n

28041 Madrid, España

Email: susana_heredero@yahoo.es

Recibido: 20.09.05

Aceptado: 18.12.05

References

1. Haugh RH, Likavec MJ. Frontal sinus reconstruction. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 1994;2:65-83. [ Links ]

2. Rohrich RJ, Hollier L. The role of nasofrontal duct in frontal sinus fracture management. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma 1996;2:31-40. [ Links ]

3. Sánchez Aniceto G. Estudio clínico epidemiológico de los traumatismos faciales en los accidentes de tráfico. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 1993. [ Links ]

4. Rohrich RJ, Hollier LH. Management of frontal sinus fractures, changing concepts. Clin Plast Surg 1992;19:219-32. [ Links ]

5. Manolidis S. Frontal sinus injuries: associated injuries and surgical management of 93 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;62:882-91. [ Links ]

6. Donald PJ, Berstein L. Compound frontal sinus injuries with intracranial penetration. Laryngoscope 1972;88:225-32. [ Links ]

7. Gervino G, Roccia F, Benech A, y cols. Analysis of 158 frontal sinus fractures: current surgical management and complications. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2000;28:133-9. [ Links ]

8. El Khatib K, Danino A, Malka G. The frontal sinus: a culprit or a victim? A review of 40 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2004;32:314-7. [ Links ]

9. Ioannides C, Freihofer HP, Friens J. Fractures of the frontal sinus: a rationale of treatment. Br J Plast Surg 1993;46:208-4. [ Links ]

10. Rohrich RJ, Micel TJ. Frontal sinus obliteration: in search of the ideal autogenous material. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;95:580-5. [ Links ]

11. Wilson BC, Davidson B, Corey JP, Haydon RC. Comparison of complications following frontal sinus fractures managed with or without obliteration over 10 years. Laryngoscope 1988;98:516-20. [ Links ]

12. Schön R, Gellrich NC, Schmelzeisen R. Frontiers in maxillofacial endoscopic surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2003;11:209-38. [ Links ]

13. Raveh J, Laedrach K, Vuiltemin T, Zing M. Management of combined fronto-naso-orbital/skull base fractures and telecanthus in 355 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;118:605-14. [ Links ]

14. Derome P. Les tumeurs sphénoethmoïdales. Possibilités d'exérèse et de réparation chirurgicales. Neurochirurgie 1972;18(Supl 1):1-164. [ Links ]

15. Sekhar LN, Nanda A, Sen CN, Snyderman CN, Janecka IP. The extended frontal approach to tumors of the anterior, middle, and posterior skull base. J Neurosurg 1992;76:198-206. [ Links ]

16. Yavuzer R, Sari A, Kelly CP, Tuncer S, Latifoglu O, Celebi C, Jackson IT. Management of frontal sins fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;115:79-93. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em