Introduction

The Internet is an integral part of modern life, but as its use has grown, it has provided a new environment in which a wide range of problematic behaviors have emerged due to its potentially addictive features (e.g., accessibility, anonymity, convenience, etc.) and/or the online activities themselves (e.g., gaming, gambling, social media use, etc.) (Anderson et al., 2017; Arrivillaga et al., 2021; Pastor et al., 2022; Rial et al., 2018; Rial et al., 2023), especially in the adolescent population (Fumero et al., 2018).

The term Problematic Internet Use (PIU) refers to a pattern of behaviors that includes exaggerated concern about connecting to the Internet being difficult controlling oneself, which affects the normal development of adolescents’ daily life, and is used to artificially alleviate their emotional state (Caplan, 2010). It covers a wide range of online behaviors, including excessive social media use, gaming, gambling, viewing pornography, and impulse buying (Anderson et al., 2017; Fineberg et al., 2018). Terminology and definitions are varied, reflecting several communalities with compulsive, addictive, and more generally problematic behaviors (Anderson et al., 2017). We use the term PIU to be consistent with prior research into excessive and maladaptive internet use behavior (Anderson et al., 2017; Caplan, 2010; Gómez et al., 2017; Pastor et al., 2022; Werling & Grünblatt, 2022).

PIU brings about several mental and physical health consequences (Andrade et al., 2021; Fineberg et al., 2018; Restrepo et al., 2020). Different forms of PIU are associated with mental disorders comorbidities, including affective and anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, loss of productivity, sleep disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and impulse-control disorders (Ioannidis et al., 2018; Menéndez-García et al., 2020). Studies also suggest that PUI may be associated with increased rates of suicidal behaviors and/or self-harm (Herruzo et al., 2023).

Nevertheless, the assessment of PIU prevalence remains challenging, as there is still significant methodological and cultural heterogeneity. Consequently, the prevalence estimates differ significantly worldwide (Cheng & Li, 2014; Dahl & Bergmark, 2020). The peak time of Internet use onset is when children are in kindergarten and early elementary school (Nakayama et al., 2020), and children’s long-term misuse and abuse might lead to PIU in adolescence (Ioannidis et al., 2018). It is a highly prevalent behavior in adolescents, varying between 5% and 15.2% in Europe, and between 2.5% and 26.8% in Asian countries (Kuss et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). Although some studies have found no differences with respect to age (Jiménez & Domínguez, 2019; Vila et al., 2018), other studies have found higher prevalence rates among younger minors (Panova et al., 2021) and yet others have found higher PIU towards the end of adolescence and early youth (Arrivillaga et al., 2021; Gómez et al., 2017; Rial et al., 2018; Xin et al., 2018). In a large-scale study among Spanish adolescents, 18.3% of late adolescents reported PIU, whereas 14.6% of early adolescents reported PIU, indicating a significantly higher risk of engaging in PIU in late adolescence (Gómez et al., 2017). Data from the Drug Use in Secondary Education Survey [Encuesta sobre Uso de Drogas en Enseñanzas Secundarias en España - ESTUDES] (Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones [OEDA, 2022]) showed that, in 2021, 23.5% of students aged 14-18 were at high risk of compulsive internet use, higher than in 2019 (20%). However, within this range, there was a higher prevalence for 16-year-olds (24.8%) compared to 18-year-olds (23.3%). With regards to gender, some studies have not found differences (Jiménez & Domínguez, 2019; Lukács, 2021; Vila et al., 2018). Other studies show higher PIU among males (Alonso & Romero, 2021; Anderson et al., 2017; Durkee et al., 2016; Kaess et al., 2016; Kuss et al., 2014) or, conversely, among females (Andrade et al., 2021; Ferreiro et al., 2017; Gómez et al., 2017; Rial et al., 2018). In Spain, recent data indicate a higher percentage among females (36.1%) compared to men (29.8%) (Andrade et al., 2021). According to the latest ESTUDES survey (OEDA, 2022), as in previous years, the prevalence was higher among females (28.8%) than males (18.4%). Age is also relevant and may intersect with gender, with younger people typically having problems with gaming and media streaming, males with gaming, gambling, and pornography viewing, and females with social media and buying (Anderson et al., 2017).

The growing research on this topic has led to the development of a lot of scales (Laconi et al., 2014). The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) (Meerkerk et al., 2009) is one of the most widely used instruments in research (Anderson et al., 2017; Kuss et al., 2014). This validated tool has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in terms of reliability and validity evidences in various countries and cultures (López-Férnandez et al., 2019; Sarmiento et al., 2020). It is a 14-item self-report on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never to 4 = very often) that covers five dimensions: loss of control (items 1, 2, 5, and 9), preoccupation (items 4, 6, and 7), withdrawal symptoms (item 14), coping or mood modification (items 12 and 13), and conflict (items 3, 8, 10, and 11) (Meerkerk et al., 2009). A recent study (López-Fernández et al., 2019) analyzed the psychometric properties of different versions (CIUS-14, CIUS-9, CIUS-7, CIUS-5) developed in eight languages (German, French, English, Finnish, Spanish, Italian, Polish, and Hungarian) and endorsed its use as valid and especially useful for its brevity. Similarly, the 14-item scale in Spanish adolescent population has also demonstrated adequate psychometric properties and a unidimensional structure (Ortuño-Sierra et al., 2022).

Lack of awareness as well as the shame and secrecy that may surround different forms of PIU may constitute important obstacles to recognition, diagnosis, and, ultimately, intervention and prevention. The main goal of this study was to analyze the prevalence of PIU among Spanish adolescents. Therefore, the specific objectives were a) to study the prevalence of PIU for the total sample; b) to analyze the possible influence of gender and age on the CIUS’ dimensions, and c) to obtain the normative data for the total sample and attending to gender identifying lower and higher levels of PIU ranges in a representative sample of Spanish adolescents.

Method

Participants

The study recruited from a population of 15,000 students from La Rioja (northern Spain). For the study we used a stratified random cluster sampling, with the classroom as the sampling unit. Thus, we recruited students from 30 schools, with a total of 98 classrooms. Then we established layers as a function of the geographical zone and the educational stage. As a result, we recruited 1,972 students. Students older than 19 years (n = 36) or a high score in the Oviedo Infrequency Scale-Revised (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2019) (more than two points) (n = 146) were deleted. Therefore, the final sample included 1,790 students, 961 female (53.7%) 816 male (45.6%), and 13 other (0.7%). Age ranged between 14 and 18 years-old and the mean age was 15.70 years-old (SD = 1.26). With regards to nationality, a total of 89.4% of participants were from Spain, 2.5% Romania, 1.9% Central and South American countries (Bolivia, Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador), 1.4% Morocco, 0.8% Pakistan, 0.3% Portuguese and 3.7% from other countries.

Instruments

Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS)

The CIUS (Meerkerk et al., 2009) included 14 items on a Likert scale of 5 options (0 = never, 4 = very often) to assess PIU. It has showed adequate evidences of validity and good reliability (Cronbach’s α between .89 and .90). In addition, other CIUS versions, such as CIUS-9 (Khazaal et al., 2012) or the CIUS-7 and CIUS-5 (Besser et al., 2017), have also shown adequate psychometric properties (López-Fernández et al., 2019; Sarmiento et al., 2020).

Oviedo Infrequency Scale-Revised (INF-OV-R)

The INF-OV-R (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2019) is a self-report instrument made up of 12 items in a 5-point Likert- scale (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree). The INF-OV-R allows detecting those participants who responded in a random, pseudorandom, or dishonest manner. In the present study, students with more than two incorrect responses on the INF-OV-R scale were eliminated from the sample.

Procedure

The questionnaires were administered collectively by computers, in groups of 10 to 30 students during normal school hours. With the aim to standardize the administration process, all the researchers had a protocol that they had to follow before, during, and after conducting the administration of the questionnaires. Participants were informed of the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of the study. No incentive was provided for their participation. All parents or legal guardian were asked to provide a written informed consent for their child to participate in the study. The present study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Clinical Research of La Rioja (CEImLAR P.I. 337).

Data Analysis

First, we calculated the descriptive statistics and the percentage distribution of the CIUS-S’ items. Second, with the aim of gathering evidence about the possible influence of gender and age on the expression of PIU, we studied the distribution of the scores attending to these two variables and we examined if there were statistically signifficant differences. Due to the small number of participants reporting other-gender identity (n = 13), only individuals who described themselves as male or female were included in these analyses (N = 1,777). A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted, where gender and age were fixed factor and CIUS’ dimensions and total score as dependent variables. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to detect specific within group differences in thoses cases where statistically significant differences were found. Finaly, we calculated normative data for the total sample and disaggregated by gender. SPSS 28.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Percentage Distribution of the CIUS-S’ Items

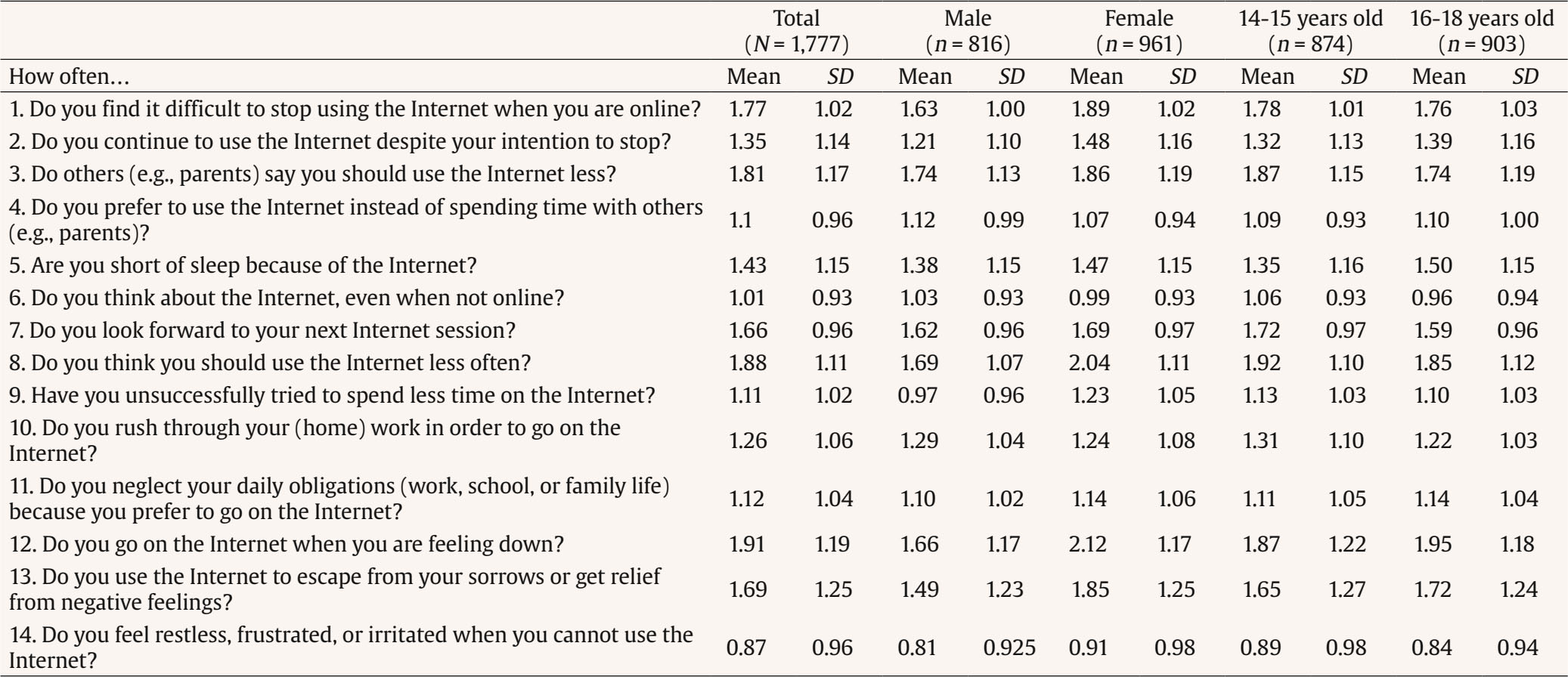

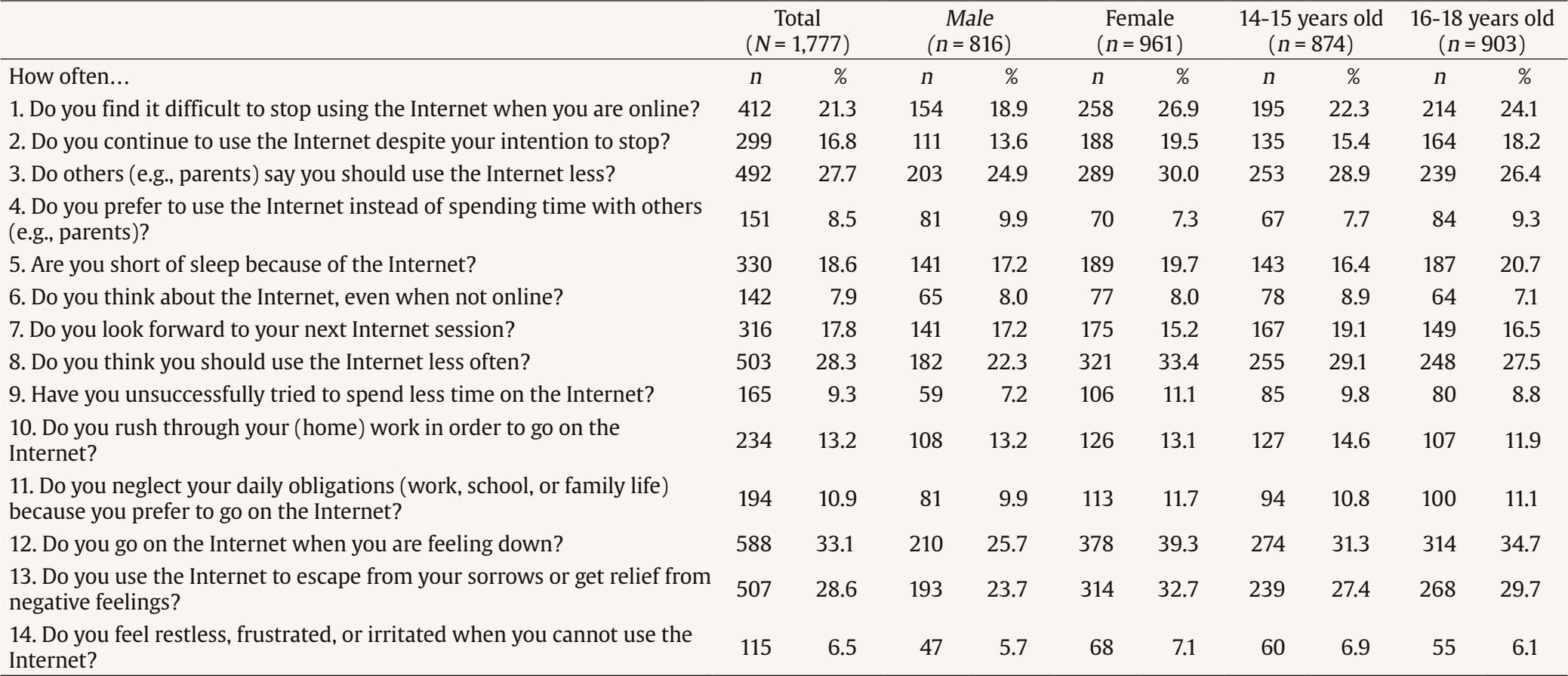

Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviations of the CIUS’ items for the total sample (N = 1,777) and according to gender (male and female) and age groups (14-15 years old and 16-18 years old). These age groups correspond to adolescent developmental stages: mid-adolescence (14-15 years) and late-adolescence (16-19 years) (World Health Organization, 2022).

Table 2 shows the numbers and percentages by age and gender who scored 3 = often or 4 = very often on the CIUS’ items. As can be seen, a total of 33.1% of participants indicated that often or very often, they “go on the Internet when they were feeling down” (Item 12). In addition, a total of 28.6% revealed that often or very often they “use the Internet to escape from sorrows or get relief from negative feelings” (Item 13). Worth noting, the percentage of women who indicated often or very often to these two items was 39.3% and 32.7%, respectively, compared to the 25.7% and 23.7% of men. On the other hand, only 6.5% of participants indicated number 3 and 4 options for the the item 14 “you feel restless, frustrated, or irritated when you cannot use the Internet” and 7.9 % revealed that they “thought about the Internet, even when not online” (Item 6). Also, only 8.5% responded to options 3 or 4 to the item 4: “do you prefer to use the Internet instead of spending time with others (e.g., parents)?”.

Problematic Internet Use by Gender and Age

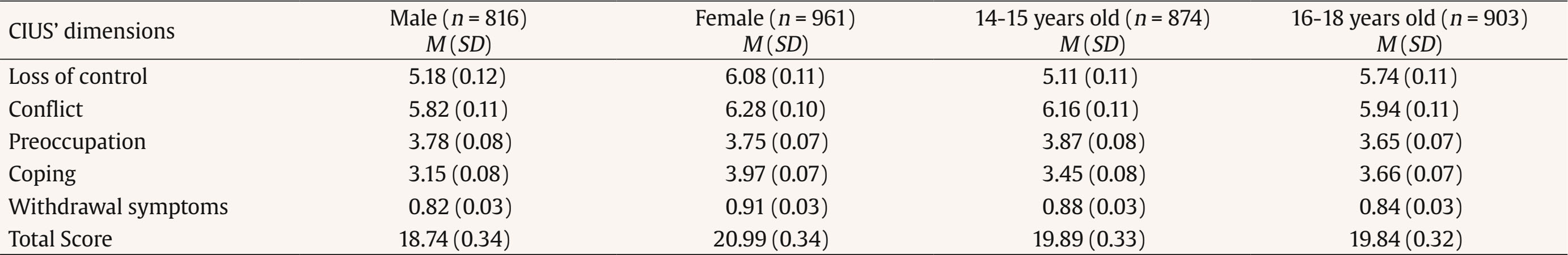

A MANOVA was conducted with gender and age as fixed factors and the CIUS’ dimensions and CIUS’ total score as dependent variables. We used Wilks’ lambda to screen for statistically signifficant differences in all the variables as a whole. As a measure of the effect size, we used partial eta square (η2). Table 3 shows mean and standard deviation of the dimensions and Total Score by gender and age. Wilks’s value λ revealed that there were statistically significant differences both by gender (Wilks’ λ = .945, p < .001) and age (Wilks’ λ = .984, p < .001).

With regards to gender, the ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences in loss of control (F = 31.853, p < .001, partial η2 = .018), conflict (F = 9.053, p = .003, partial η2 = .005), coping (F = 58.487, p < .001, partial η2 = .032), withdrawal symptoms (F = 3.881, p = .049, partial η2 = .02), and CIUS’ total score (F = 24.179, p < .001, partial η2 = .013). No statistical differences were found in preoccupation. With regards to age, the ANOVA values showed statistically significant differences in preoccupation (F = 21.983, p = .036, partial η2 = .002). No statistical differences were found in the other dimensions, nor in the CIUS’ total score.

Normative Data for the Total Sample and Attending to Gender

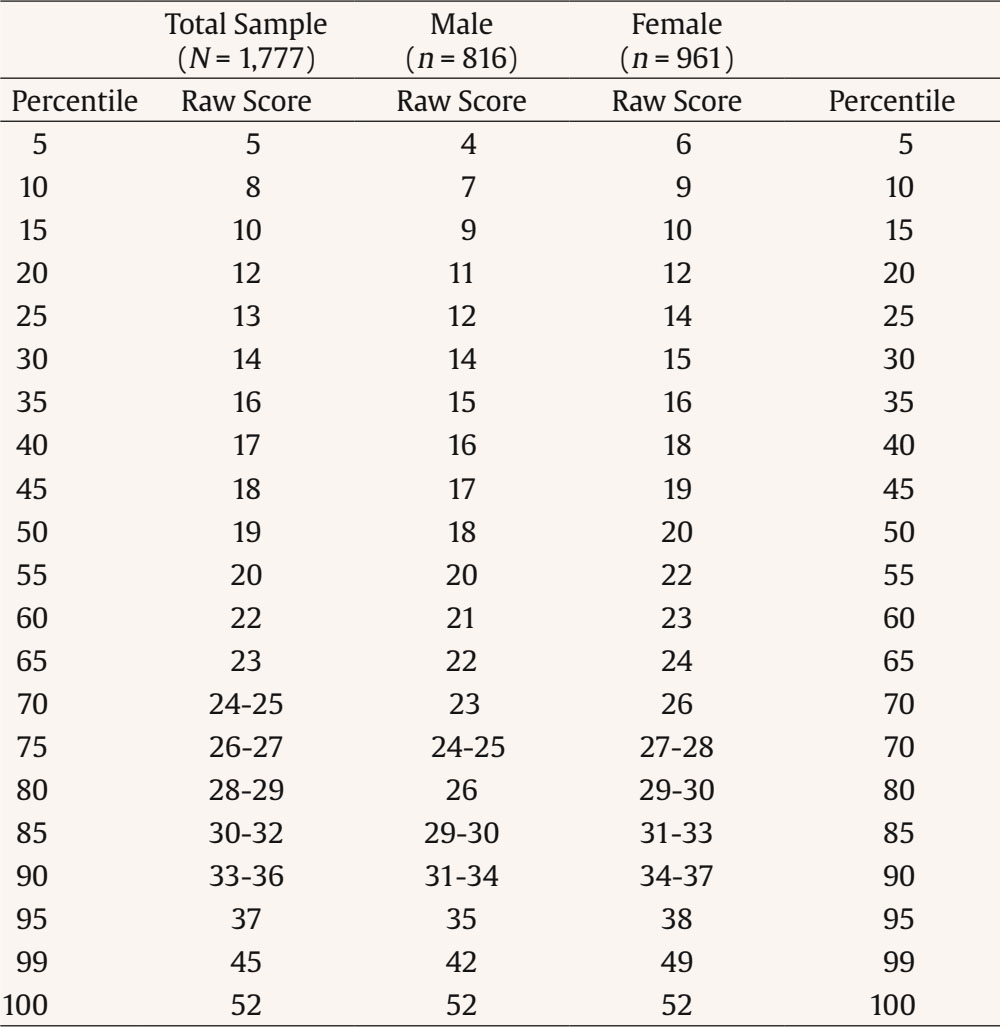

Once statistically signifficant differences in the total score were found by gender and not by age, we studied the normative data independently for the CIUS’ total score separately considering to male and female. As can be seen in Table 4, the previously proposed cut-off score of 18 for “mild level of addiction” (Guertler et al., 2014) included a total of 55% of the total sample. The suggested cut-off point of 23 for “high level of addiction” (Guertler et al., 2014) included a total of 35% of the sample. By gender, 60% of the females showed a ”mild level of addiction” and a total of 40% a “high level of addiction” compared to 50% and 30% of males revealing “mild and high level of addiction”, respectively.

Discussion

Young people use the Internet as an integral part of their daily life with its advantages and disadvantages (Andrade et al., 2021; Arrivillaga et al., 2021; Ferreiro et al.,2017; Lukács, 2021; Pastor et al., 2022). Adolescence represents a critical developmental period in which prominent changes occur in biological, social, and cognitive domains (Aritio-Solana et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022). For this reason, adolescence is considered as a period of life with a particular vulnerability to different psychological and mental health difficulties, including behavioral addictions such as problematic Internet use (PIU) (Kuss et al., 2014).The main goal of the present study was to analyse the prevalence of PIU among the Spanish adolescent population and the possible influence of gender and age in the expression of this pheonomenon.

Data found reveal that a total of 33.1% of adolescents used the Internet often or very often when they were feeling down and a total of 28.6% indicated that often or very often, they used Internet to escape from sorrows or get relief from negative feelings. By gender, the percentages of PIU increased among women. This aligns with other studies that have also found the use of the Internet as a tool for escaping reality and coping with negative emotional states (Andrade et al., 2021; Caplan, 2010). This is considered a maladaptive strategy to reduce one’s levels of distress and it could inhibit the possibility of developing more adaptive and effective coping strategies in the long term (Spada & Marino, 2017). Moreover, a recent study found that low emotional regulation is part of the profile of adolescents with PIU (Arrivillaga et al., 2021).

Related to the interference in daily life, 7.9% revealed that often or very often they thought about the Internet, even when not online. A recent study showed that a quarter of Madrid’s adolescents between 12 and 16 years of age stated that they had acquired the ability to self-regulate the use of their smartphone and around 15% stated that they had significant difficulties in this regard (Pastor et al., 2022). Nonetheless, another study also found that “failure to stop” was one of the central symptoms in the expression of PIU (Liu et al., 2022). Another relevant aspect found in our study was that a total of 8.5% prefer to use the Internet instead of spending time with others (e.g., parents, friends). Some studies have also found a relationship between PIU and social isolation and a notable decrease in family and peer group relationships (Lukács, 2021). Finally, a 6.5% indicated that they feel restless, frustrated, or irritated when they cannot use the Internet. Although a cause-effect relationship cannot be established (Odgers & Jensen, 2020), levels of emotional well-being and life satisfaction appear to be lower among adolescents with PIU (Alonso & Romero, 2021; Anderson et al., 2017; Andrade et al., 2021; Fineberg et al., 2018; Lukács, 2021). These aspects, as well as the cluster of symptoms of compulsive use like withdrawal and tolerance, are crucial characteristics in the development of PIU during adolescence (Liu et al., 2022).

The present study provided evidence about the influence of gender and age in the expression of PIU. Previous studies have had mixed findings with respect to gender with generally higher scores in males (Alonso & Romero, 2021). However, we found females to score more highly, and no relationships with age. This is consistent with other studies evidencing higher levels of PIU among women (Andrade et al., 2021; Ferreiro et al., 2017; Gómez et al., 2017; Rial et al., 2018). For instance, in the Spanish context, the ESTUDES survey (OEDA, 2022) showed higher levels of PIU among females (28.8%) compared to males (18.4%). Moreover, we found statistically significant differences in CIUS’ dimensions by gender in loss of control, conflict, coping, withdrawal symptoms, and in the CIUS’ total score and by age in preoccupation. Regarding to normative data, our results have shown that there are more females that can be considered at “mild level of addiction” and “high level of addiction”. Given the adverse impact on adolescents, it is of great significance to investigate the development of PIU in this population (Dahl & Bergmark, 2020). In addition, it is important to note that addictive behaviors developed during this time are likely to continue into adulthood (Anderson et al., 2017). In response to the emerging public health importance of PIU, the newly created European Problematic Use of the Internet (EU-PUI) Research Network includes among its priorities the following areas for different forms of PIU: reaching a consensus on conceptualization, describing and defining the diagnostic criteria, developing and validating reliable tools, and quantifying the clinical and health economic impact (Fineberg et al., 2018). Recently, literature suggests the importance of school-based prevention programs to address addictive behaviours and other mental health problems related to PIU (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2023; González-Roz et al., 2023).

The present study has some limitations. First, it is based on a self-report instrument and there are well-known problems related to this kind of measure. Future works may benefit from the use of experimental data (e.g., behavioral recording, neuroimaging) or studies including parents, teachers, or relatives who could provide valuable information. Second, we conducted a cross-sectional study, but future longitudinal studies could analyze cause-effect relationships. Third, the study focused on a specific Spanish region and more studies analyzing other Spanish regions and countries would be advisable.

Notwithstanding these limitations, PIU is commonly regarded as a potential mental health problem that triggers serious physical and psychological consequences, and it is particularly harmful for adolescents. This study contributes to clarify the prevalence of the PIU among the Spanish adolescent population. Future research should continue gathering new data about it in other contexts and cultures and introduce new methodologies, as ambulatory assessment (Elosua et al., 2023).