Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychosocial Intervention

versión On-line ISSN 2173-4712versión impresa ISSN 1132-0559

Psychosocial Intervention vol.23 no.1 Madrid abr. 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.5093/in2014a6

Psychosocial adjustment in aggressive popular and aggressive rejected adolescents at school

Ajuste psicosocial en adolescentes populares agresivos y rechazados agresivos em el colégio

Estefanía Estéveza, Nicholas P. Emlerb, María J. Cavac y Cándido J. Inglésa

a Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche, Spain

b University of Surrey, England

c Universitat de València, Spain

This study was performed within the framework of the research project PSI2008-01535/PSIC: "School violence, victimization and social reputation in adolescence" subsidized by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of the present study was to compare the profiles of aggressive adolescents who differed in social status in the classroom, popular vs. rejected, with those of adolescents of average sociometric status without documented behavior problems. The characteristics compared related to intra-individual, family, school, and social domains. A sample of 457 adolescents, aged 11 to 18 years old (48% girls), participated in the study. Differences between groups were examined via a series of multivariate analyses of variance and discriminant function analyses. Results indicated that although aggressive popular adolescents revealed more academic involvement and social integration in the classroom, their levels of emotional and family adjustment were as adverse as those of aggressive rejected students. Both groups held negative attitudes towards the institutional authority of teachers together with commitment to a social image based on a rebellious and nonconformist reputation among peers. Implications of the findings and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: Adolescence Aggressive rejected Aggressive popular Psychosocial adjustment Sociometric status

RESUMEN

El objetivo del presente estudio fue comparar el perfil de adolescentes agresivos con distinto estatus sociométrico en el aula, populares o rechazados, con adolescentes de estatus sociométrico promedio y sin problemas de conducta documentados. Se compararon características a nivel intra-individual, familiar, escolar y social. Una muestra de 457 adolescentes de entre 11 y 18 años (48% chicas) participaron en el estudio. Las diferencias entre los grupos se examinaron a través de una serie de análisis multivariados de varianza y de función discriminante. Los resultados indicaron que aunque los adolescentes populares agresivos mostraron un mejor desempeño académico e integración social en la clase, sus niveles de ajuste emocional y familiar fueron tan negativos como los de los estudiantes rechazados agresivos. Ambos grupos informaron de actitudes negativas hacia la autoridad institucional de los profesores, así como el compromiso con una imagen social entre los iguales fundamentada en la reputación de rebeldía y no conformismo. Se discuten la implicación de los resultados y sugerencias para investigaciones futuras.

Palabras clave: Adolescencia. Rechazados agresivos. Populares agresivos. Ajuste psicosocial. Status sociométrico

The degree of social acceptance among peers at school and, more specifically, the social status of the student is key to psychosocial adjustment and academic success in adolescence (Bierman, 2004; Estévez, Martínez, & Jiménez, 2009). Sociometric techniques have been traditionally used to analyse the social position of every adolescent in a group, allowing classification of students into differentsociometric statuses, namely popular, rejected, ignored, controversial, and average (Gifford-Smith & Brownell, 2003). Characteristics associated with these sociometric types have been documented in numerous studies (Maag, Vasa, Reid, & Torrey, 1995; Schwartz, Gorman, Nakamoto, & McKay, 2006; Vaillancourt & Hymel, 2006).

The present study focuses mainly on the popular and rejected statuses, the main distinguishing features of which highlighted in the scientific literature are the following : popular adolescents, who are liked by the majority of the group, have some prestige among their classmates, show greater social competence, and better behavioral adjustment compared to the other sociometric types; rejected adolescents, in contrast, are regarded as unpleasant by most of their peers, report more conflictual relationships with other classmates and teachers and have low social and academic competence, being more frequently involved in disruptive and aggressive behaviors that lead to the violation of institutional rules (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982; Newcomb, Bukowski, & Pattee, 1993). Level of aggression is a commonly reported difference between popular and rejected adolescents, though recent studies indicate that not all rejected adolescents are aggressive and not all popular adolescents are well adjusted (Estell, Farmer, Pearl, Van Acker, & Rodkin, 2008; Estévez, Herrero, Martínez, & Musitu, 2006; Hoff, Reese-Weber, Schneider, & Stagg, 2009).

Although earlier studies of rejected adolescents focused on their high levels of aggression (Bierman, Smoot, & Aumiller, 1993), more recent work suggests that rejected students do not constitute a homogeneous group (Graham & Juvonen, 2002) - some adolescents in this category show excessive social withdrawal, itself a possible risk factor for social rejection by peers (Estévez, Herrero et al., 2006). At least two groups have been identified within the rejected category (Harrist, Zaia, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 1997): 40-50% display aggressive behavior (Astor, Pitner, Benbenishty, & Meyer, 2002; Parkhurst & Asher, 1992) and the remainder display timidity and passivity (Cillessen, van Ijzendoom, van Lieshout, & Hartup, 1992; Verschueren & Marcoen, 2002) but not behavioral problems (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 1998).

Defining characteristics of the popular status include high levels of pro-social behavior (for instance, cooperation, helping others, kindness) and low levels of aggressive behavior (Newcomb et al., 1993; Rubin et al., 1998). However, recent research has shown that some popular adolescents display aggression at school (Becker & Luthar, 2007). Thus, it seems that some openly violent students are positively connected with the social network of the classroom and achieve a degree of centrality in the group (Estell, Cairns, Farmer, & Cairns, 2002; Gest, Graham-Bermann, & Hartup, 2001; Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl, & Van Acker, 2000, 2006).

However, while research on psychosocial adjustment has traditionally focused on the rejected status due to its strong association with problems of emotional and behavioral wellbeing (Miller-Johnson, Coie, Maumary-Gremaud, & Bierman, 2002), studies examining the adjustment of adolescents with popular status are fewer in number, due perhaps to the smaller proportion of such students showing behavioral problems. Research into the characteristics of adolescents with high status in the classroom is, however, essential in developing our knowledge of the complex relationship between popularity and aggression. The importance of such a work lies in its potential for explaining why some classmates' deviant and aggressive behavior is accepted by peers (Hoff et al., 2009).

Results from previous studies suggest that differences between aggressive popular and aggressive rejected students may exist in the intra-individual, family, school, and social domains (Gifford-Smith & Brownell, 2003; Ladd, 1999). However, no previous studies have concurrently analyzed the diverse contexts in which differences between groups may occur.

Intra-individual Level

Previous investigations have shown that popularity at school is related to psychosocial adjustment in adolescence, while rejection by peers is a significant risk factor for the development of emotional adjustment problems (Kupersmidt, Coie, & Dodge, 1990; Pettit, Clawson, Dodge, & Bates, 1996). Thus, social rejection has been associated with indicators of maladjustment such as anxiety, stress, presence of depressive symptoms (Coie, Lochman, Terry, & Hyman, 1992; Estévez, Herrero et al., 2006; Kiesner, 2002), feelings of loneliness, and low satisfaction with life (Hay, Payne, & Chadwick, 2004; Woodward & Fergusson, 1999). Rejected adolescents, compared to their popular peers, perceive themselves as socially less capable and have less positive expectations of social success, so they make fewer attempts to establish social interactions and, as a consequence, they are at greater risk of developing severe social isolation which in turn contributes to their emotional impairment (Estévez et al., 2009).

The frequency and type of social interactions that adolescents establish are also related to the development of their empathic ability. Some authors have suggested that rejected adolescents have an emotional deficit associated with information processing problems, which is often translated into difficulties in handling social situations requiring empathy. Thus, rejected adolescents are more likely to attribute hostile intentions to their peers in ambiguous situations (Crick & Dodge, 1994), with the result that they respond inappropriately to interpersonal signs and intentions, without considering the effects of their reactions or others' feelings (Gifford-Smith & Brownell, 2003; Ladd, 1999). Empathy has seldom been analyzed in studies on popularity in adolescence, although the limited data available suggest that popular adolescents have higher levels of empathy (Pakaslahti, Karajalainen, Keltikangas, & -Jarvinen 2002). These results, however, are from studies in which no distinction was made between aggressive and non-aggressive adolescents, the samples being confined to popular adolescents lacking documented behavioral problems.

Family Level

The quality of family relationships is closely related to the behavior that children develop in their social interactions in other contexts such as the school (Gracia, Lila, & Musitu, 2005; Helsen, Vollebergh, & Meeus, 2000; Musitu & Cava, 2001; Musitu & García, 2004). Various studies have concluded that rejected adolescents perceive their families as lacking cohesion and as highly conflictual (Cava & Musitu, 2000; Ladd, 1999). Likewise, the use of dysfunctional strategies to deal with family conflicts, such as threatening, insulting, verbal hostility, defensive attitudes, isolation, and physical violence, is associated in childhood with greater negative emotionality and school rejection, and a tendency to use violence as a way of solving social conflicts (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2003). Similarly, adolescents rejected by their peers usually report the presence of negative and offensive family communication (Black & Logan, 1995; Estévez, Herrero et al., 2006; Helsen et al., 2000), and low parental support (Estévez, Martínez, Moreno, & Musitu, 2006).

Conversely, an affective family relationship based on open and empathic communication has been positively related to social competence in children, academic success, peer acceptance, and behavioral adjustment (Ladd, 1999; Lila, García & Gracia, 2007; Lila, Musitu, & Buelga, 2000; Parke, 2004; Patterson, Kupersmidt, & Griesler, 1990). The few studies on popularity and family adjustment indicate that families of popular adolescents are characterized by a warm and inductive communication style (Franz & Gross, 2001). It is important to stress, however, that these data come from samples in which the degree of behavioral adjustment was not assessed. Therefore, findings are inconclusive regarding the family environments of aggressive popular adolescents.

School Level

Rejected students show more academic difficulties, school failure, and dropout compared to others (Bellmore, 2011; Buhs, Ladd, & Herald, 2006; Greenman, Schneider, & Tomada, 2009; Jimerson, Durbrow, & Wagstaff, 2009). This fact, moreover, negatively affects their academic self-evaluations or school self-esteem (Hymel, Bowker, & Woody, 1993). Rejected adolescents have also been found to have more negative attitudes toward studies and the school, this negative evaluation being more marked in the aggressive rejected subgroup (Estévez, Herrero et al., 2006), which could explain, at least partly, their poor academic motivation (Wentzel & Asher, 1995).

Another important feature of the school context is the student-teacher relationship, given the essential role of teachers in their students' academic performance and social adjustment in the classroom (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Koth, Bradshaw, & Leaf, 2008; Murray & Greenberg, 2001; Zettergren, 2003). It has been observed that both quality of the teacher-student relationship and perceived support from the teacher are related to students' academic goals (Davis, 2003). In this regard, some studies have concluded that rejected adolescents tend to perceive less help and more criticism from teachers (Cava & Musitu, 2000). This is, in fact, one of the reasons why students are often reluctant to seek help, believing that doing so will not resolve and may exacerbate the situation (Newman & Murray, 2005. The negative teacher-student relationship is particularly evident in the case of aggressive rejected adolescents (Birch & Ladd, 1998). In contrast, it has been documented that teachers and students with high sociometric status usually interact in a positive manner (Blankemeyer, Flannery, & Vazsonyi, 2002). These studies, however, offer no insight into the relationship of teachers with aggressive popular adolescents.

Finally, rejected students, who have fewer friends within the classroom (Zettegren, 2005), also have less access to social support from peers, this constituting a significant barrier to participation in social learning experiences with other classmates. Eventually, a negative cycle can be established, with the tragic consequence of a significant decrease of both interpersonal resources - social capital - and intrapersonal resources such as self-esteem (Estévez, Martínez et al., 2006b). The gap in our knowledge again relates to the aggressive popular subgroup, about whose friendship networks no comparable data exist.

Rose, Swenson, and Carlson (2004) found that aggressive adolescents who were also perceived as popular (but not as defined by sociometric popularity) were particularly advantaged in terms of friendship quality, compared to aggressive and disliked students. Thus, while rejected students normally show more difficulties in the development of positive social interactions (Deptula & Cohen, 2004), popular students have a behavioral repertoire that seems to guarantee social success among their peers (Newcomb et al., 1993).

Social Level

Students' social positions among peers are closely related to their level of social self-esteem. Cava and Musitu (2001) found that the social self-esteem of popular - and also average - adolescents was significantly higher than that of rejected students. The high social self-esteem of popular adolescents can be explained by at least two facts; one is that they feel liked by most of their classmates, and the other is that they usually are the central figures in their own circle of friends (Gest et al., 2001). In fact, positive identification with a reference group seems to be higher in adolescents who enjoy peer acceptance, along with those who do not exhibit behavior problems, as pointed out in the study on quality of friends by Gifford-Smith and Brownell (2003). Data on level of self-esteem and group identity among popular adolescents who also display aggressive behavior is not currently available; providing such an evidence is one aim of the present study.

Closely connected to quality of and identification with friendships is the important role played by reputation among adolescent peers and its relationship with both sociometric status and aggressive behavior. A nonconformist and antisocial reputation among classmates may be sought through participation in aggressive and antisocial acts, reflecting the social image teenagers seek to transmit (Estévez, Jiménez, & Moreno, 2010; Moreno, Estévez, Murgui, & Musitu, 2009). Getting involved in this type of behavior can be understood, from this perspective, as seeking a reputation based on respect, leadership, power within the group, and nonconformity (Carroll, Green, Houghton, & Wood, 2003; Carroll, Houghton, Hattie, & Durkin, 2001). Some adolescents may make this choice as a preventative strategy, hoping in this way to avoid future victimization or rejection, while for others it may be seen as a means to achieve desired popularity among peers (Emler, 2009; Emler & Reicher, 2005). Whatever the case, although the relationship between nonconformist reputation and aggressive behavior is well supported, the link between sociometric status and desire to acquire an antisocial reputation among classmates has yet to be studied.

The Present Study

Most investigations on sociometric status at school have focused on the rejected group due to its documented risk for developing maladjustment problems, while studies on adolescents with high social status positions are more infrequent, since popularity among peers has traditionally been associated with sociability, friendship, cooperation, help, prosocial behavior and, more generally, better psychosocial adjustment (Rubin et al., 1998). However, neglecting the heterogeneity of the popular status has serious consequences; adolescents who combine their popularity with deviant behaviors are ignored in prevention and intervention programs designed almost exclusively for rejected students (Rodkin el al., 2000).

The purpose of the present study was to compare the profiles of those adolescents with high and with low social status in the classroom but both showing aggressive behavior, with respect to those variables highlighted in the literature as potential differentiating factors. In particular, the study compared aggressive popular and aggressive rejected adolescents with respect to adjustment variables in the individual, family, school and social domains. The individual level included depressive symptoms, perceived stress, satisfaction with life, feelings of loneliness, and empathy. The variables analyzed at family level were affective cohesion, family communication/ expressiveness, and family conflict. The school level included academic self-esteem, involvement in homework, friendships within the classroom, perception of help from the teacher, attitude toward the school, and teachers' evaluation of students' school adjustment. Finally, variables included at the social level were social self-esteem, group identity, and nonconforming reputation. Profiles of aggressive rejected and aggressive popular students were in turn compared to a control group of adolescents with average sociometric status and without documented behavior problems.

Related to the objectives of the study and taking into consideration results from previous research on aggression in adolescence and rejected and popular status, the hypotheses proposed in the present work were the following: (1) aggressive rejected students would obtain higher scores on measures of depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and feelings of loneliness, while popular aggressive students would report more satisfaction with life and empathic skills; (2) the aggressive rejected group was expected to perceive their families as less cohesive, more conflictual and having more communication problems, compared to the aggressive popular group; (3) aggressive rejected adolescents would show lower levels of academic self-esteem, less involvement in homework, and have fewer friends within the classroom, more negative attitudes toward teachers and the school, and more negative teacher's evaluations of school adjustment, when compared to aggressive popular adolescents; (4) at the social level, it was expected that aggressive rejected adolescents would report lower levels of social self-esteem and group identity, and that both groups, consistent with their aggressive behavior, would identify with a nonconforming reputation among peers; and (5) adolescents in the control group would inform of a better adjustment in all domains in comparison to aggressive rejected and aggressive popular students.

Method

Participants

The data for this study were derived from a larger research project on psychosocial adjustment in adolescence with a total sample of 1795. All participants were classified in terms of sociometric status and aggressive behavior following the criteria established by Coie et al. (1982). For the present study three groups were identified: aggressive rejected (n = 72), aggressive popular (n = 35), and controls (n = 350).

To be classified as either aggressive-rejected or aggressive-popular, participants had to obtain a score above the 75th percentile for aggressive behavior (3rd quartile). The scores were standardized by classroom and gender (Coie et al., 1992; Zakriski & Coie, 1996). This cut-off strategy is quite restrictive and ensures that those classified as 'aggressive' in the present study were indeed those who obtained the highest scores on this behavioral measure (Cava, 2011; Cava, Buelga, Musitu, & Herrero, 2011). The control group contained participants with an average sociometric status and scores below the 50th percentile on aggressive behavior. The remaining participants who did not meet the classifying criteria were excluded from the subsequent statistical analyses. Missing data were present in 7% of participants in the final sample of 457 adolescents, which were handled by the use of maximum likelihood estimation (Peugh & Enders, 2004).

Both samples, the original and that selected for the present study, were balanced in gender (52% males and 48% females) and were composed of 11 to 18 year-old students (M = 14.2, SD = 1.68) registered in nine charter and public schools of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, Spain. The participants were students of Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate. Classrooms had an average of 35 students. Data were collected at the end of the academic year, in order to guarantee that students were sufficiently well acquainted with one another to provide sociometric data.

Procedure

First an explanatory letter was sent to the educational centers selected with the aim of presenting the research project to the management team. Subsequently, the school and high school managers were contacted by telephone and an interview was arranged in which the project was explained in detail and voluntary collaboration was sought. With the approval of the school principals, a briefing was organized with the teaching staff in order to introduce the purpose and scope of this study. Once schools had agreed to participate, an explanatory letter was sent to students' parents through the school management requesting consent for their child's participation. Parents were requested to reply in writing if they did not wish their child to participate. No refusals were received.

Participants completed the measures in their usual classrooms in group sessions of approximately 45 minutes, within regular school hours. The running order for the instruments was counterbalanced across classrooms and schools to control for order effects. Prior to the self-completion of the scales, participants received an introductory explanation of the study and they were informed about the importance of their participation in the research. They were assured that the data provided would remain confidential throughout the whole research process and that this information would be used exclusively for the purposes of the study. They were also informed that their personal data would be anonymous, and that they were free to leave the study at any time. All adolescents collaborated voluntarily and without receiving any payment. Instruments were administered by a team of expert and trained researchers who were unknown to the participants. In each classroom, two researchers had the task of supervising completion of the instruments and answering students' questions. Finally, teachers-tutors also completed a scale providing additional information about each of their students (the teacher's perception of student adjustment scale).

Instruments

Depressive symptoms. The 7-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) translated into Spanish by Herrero and Meneses (2006) was used to ask about the presence of depressive symptoms on a scale from 1 (never or rarely) to 4 (always or most of the time). Although the CES-D can be scored for several dimensions, we used the general index of depressed mood. This index does not reflect depression itself but symptoms that are related to it (e.g., "During the last week, I have been feeling sad").

Perceived stress. The items selected for measuring the stress perceived by adolescents were taken from the instrument created by Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein (1983) and later modified by Cohen and Williamson (1988). In the present study, we used the four-item version adapted to Spanish by Herrero and Meneses (2006). This scale measures the degree to which the teenager assesses certain situations as stressful over the last month (for example, "Within the last month, I felt I was unable to control the most important aspects of my life"), with a response scale from 1(never)- to 5 (always).

Satisfaction with life. The 5-item scale created by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin (1985) was used in its Spanish version (Atienza, Pons, Balaguer & García-Merita, 2000) to measure participants' satisfaction with life. The items provide a general rating of satisfaction with life in terms of subjective well-being (e.g., "My life is, in most aspects, as I would like it to be"; response scale: 1 - strongly disagree - to 4 - strongly agree).

Feelings of loneliness. Feelings of loneliness were assessed with Russell, Peplau and Cutrona's (1980) scale in its Spanish version (Expósito & Moya, 1993). This 20-item instrument assesses perceived degree of loneliness (e.g., "How frequently do you feel the lack of company"; response scale from 1 = never to 4 = always).

Empathy. Empathy was assessed with the Scale of Empathy for Children and Adolescents (IECA) created by Bryant (1982), an adaptation for a child/adolescent population of a scale for adults (Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972). Participants completed a 22-item Spanish version (Mestre, Pérez, Frías & Samper, 1999) assessing general level of empathy experienced in different situations (e.g., "I feel bad when I see somebody gets hurt by others"; four-point response scale, from 1 = never to 4 = always).

Interpersonal relationships within the family. The Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos,1981), in its Spanish version (Fernández-Ballesteros & Sierra, 1989), was selected to provide a measure of the perception of the quality of the teenager´s family relationships. This instrument consists of 90 dichotomous items with true-false choices and grouped into 10 subscales: Affective Cohesion, Expressiveness, Conflict, Independence, Fulfillment, Intellectual-Cultural Orientation, Recreational Orientation, Morality-Religiosity, Organization and Control. These 10 subscales are grouped, in turn, into three broad dimensions describing the family environment: Interpersonal Relationships, Personal Growth and System Maintenance. In this study, we used the Interpersonal

Relationships dimension based on the subscales Affective Cohesion, Expressiveness and Conflict. The dimension Affective Cohesion (9 items) describes the degree to which the teenager perceives the existence of commitment and mutual support among family members (e.g., "In my family we really support and help each other"). The dimension Expressiveness (10 items) asks about perception of the degree to which family members express their feelings and opinions freely (e.g., "The members of my family often keep their feelings to themselves"). Finally, the dimension Conflict reflects the degree to which open conflicts between family members are perceived (e.g., "The members of my family are at odds with each other").

Interpersonal relationships at school. The Classroom Environment Scale (CES; Moos & Trickett, 1973) in its Spanish version (Fernández-Ballesteros & Sierra, 1989) was selected to assess perceived quality of social relationships at school. This instrument consists of 90 dichotomous items, with true-false choices and grouped into 9 subscales; we used only the Interpersonal relationships dimension, based on three subscales: Involvement, Affiliation, and Support from the Teacher. Involvement measures perceptions of students as interested and participating in the activities of the classroom (e.g., "The students show a lot of interest in what they do in this classroom"). The dimension Affiliation refers to the perception that students have about the degree of friendship and cohesion between the classmates (e.g., "In this classroom, the students really get to know each other well"). The dimension Support from the Teacher refers to perception of the degree of help, concern, and friendship that the teacher shows toward the students (e.g., "This teacher shows particular interest in their students").

Attitude toward the school and the teachers. The items to measure the students' attitude toward the school and the teachers were taken from two previous scales assessing attitude toward institutional authority, created by Reicher and Emler (1985) and Rubini and Palmonari (1995). The final version of the instrument used in the present investigation consisted of 10 items (four-item response scale; 1 = totally disagree, 4 = totally agree) assessing attitude toward studies and teachers. The psychometric properties of this last version have been recently evaluated, showing this scale adequate reliability coefficient (Cava, Estévez, Buelga, & Musitu, 2013).

Teacher's perception of student adjustment. The instrument designed by García-Bacete (1989) to measure the teacher's perception of the student's school adjustment, and adapted by Cava and Musitu (1999) consists of 8 items with a response scale of 1 (very low/very bad) to 10 (very high/very good). Each teacher assessed each of their students on four aspects: social adjustment of the student in the classroom (e.g., "The relationship of the student with his/her classmates"); academic performance (e.g., "Student´s level of academic effort"); family involvement (e.g., "Degree of involvement of the family in the student´s school monitoring -attendance at meetings, contact with the tutor, school activities"); and the relationship between the teacher and the student (e.g., "Your relationship with this student").

Social and academic self-esteem. The social and academic dimensions of self-esteem were measured using Musitu, García, and Gutiérrez's (1994) AF5 Questionnaire. The social self-esteem subscale of this instrument consists of 6 items relating to self-perceived competence in social relationships. The items have 5-point response scales (1 = never, 5 = always). The social dimension combines two aspects, one referring to the respondent's social network and their ease or difficulty in maintaining or expanding that network (e.g., "I make friends easily"), the other to individual qualities that are important for interpersonal relationships (e.g., "I am a happy boy/ girl"). The academic self-esteem subscale consists of 6 items assessing self-perceived quality of academic performance. This dimension combines two aspects, one about specific qualities valued in school, such as intelligence and study habits (e.g., "I do my homework properly"), the other about teachers' reactions (e.g., "My teachers consider me to be a good student").

Group identity. We used Tarrant's (2002) Social Identification Scale in its Spanish version (Cava et al., 2011). This instrument is based on Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1981; Turner, 1982). The scale's 13 items cover three aspects of identification: cognitive, or respondent´s perception of self as a member of the group (e.g., "I feel myself to be part of this group"); evaluative, respondent´s valuation of the group (e.g., "I am ashamed of belonging to this group"); and affective, degree to which the respondent feels free, comfortable and committed to the group (e.g., "I do not feel free in this group"). These 13 items are answered on 10-point scales (0 = completely disagree, 10 = completely agree).

Nonconforming ideal reputation. We used the items from the dimension Ideal Public Self of the Social Reputation Scale created by Carroll, Hattie, Durkin and Houghton (1999; bidirectional translation English-Spanish). This dimension consists of 7 items referring to an adolescent's perception of his/her ideal reputation as a nonconforming and rebellious person in the peer group (e.g., "I would like others to think I am a thug", "I would like others to think I do things against the law"; four-point response scale, 1 = never, 4 = always).

Sociometric status. Data on sociometric status were generated using the peer nomination method proposed by Jiang and Cillessen (2005). Participants were asked to nominate three classmates whom they liked most (positive nomination) and three classmates whom they liked least (negative nomination). Following Coie et al. (1982) criteria, indices of social preference and social impact were calculated from nominations scores. Each participant's social preference score was defined by the standardized number of nominations as being most liked minus the standardized number of nominations as being least liked. The social impact score was calculated by adding the standardized number of nominations received for being most liked and least liked. To assign adolescents to sociometric categories, procedures outlined by Coie et al. were followed: the popular group consisted of all adolescents who received a standardized social preference score above 1, a standardized most liked score above 0, and a standardized least liked score below 0; the rejected group consisted of all those with a standardized social preference score below 1, a standardized most liked score below 0, and a standardized least liked score above 0. In the sociometric literature, stability is usually found to be lower for younger adolescents than for older adolescents. Other reliability indices, such as Cronbach's alpha, are rarely used due to theoretical difficulties when conceptualizing sociometric measurement within a classical psychometric framework (Terry, 2000).

Aggressive behavior at school. Aggressive behavior at school was measured using the Aggressive Behavior Questionnaire of Little, Henrich, Jones and Hawley (2003; bidirectional translation English-Spanish) in its 25-item version. These items assess, with an answer range of 1 = never to 4 = always, two types of violent behavior. On the one hand, they measure three functions of Manifest or Direct aggression: pure (e.g., "I am a person who fights with others"), reactive (e.g., "When somebody hurts me, I hit back"), and instrumental (e.g., "I threaten others to get what I want"). On the other hand, they also assesses three functions of Relational or Indirect aggression: pure (e.g., "I am a person who does not allow others to come into my group of friends"), reactive (e.g., "When somebody gets angry with me, I tell my friends to avoid contact with that person"), and instrumental (e.g., "To get what I want, I either treat others with indifference or stop talking to them"). This factorial structure was replicated in this sample through a confirmatory factor analysis with the AMOS program (software version 6.0, Arbuckle 2005), with good indicators of fit (GFI = .91, RMSEA = .059).

Results

We first examined whether sociometric status was independent of gender via a 2 (gender) by 2 (rejected and popular status) Chi-square analysis. This revealed that sociometric status was not independent of gender, ~2(2) = 16.67, p < .001. Of 72 aggressive rejected adolescents, 76.4% (n = 55) were boys and 23.6% (n = 17) were girls, while of aggressive popular adolescents, 57.1% (n = 20) were boys and 42.9% (n = 15) were girls. Due to the size of the groups, however, the subsequent analyses did not include gender as a classification variable but as a control covariate.

Following this, we carried out a series of multivariate analyses ofvariance (MANOVA) in order to examine significant relationships between peer-nominated status and the adjustment indicators considered in the study. Due to the existence of very different cell sizes and lack of homogeneity of variance, the robust estimators of Brown and Forsythe (1974) and Welch (1951) were used in the analyses for F estimation.

Individual Variables and Sociometric Status Differences

To evaluate whether aggressive rejected, aggressive popular, and the control group differed in the individual adjustment variables, a MANOVA was performed with depressive symptomatology, perceived stress, satisfaction with life, feelings of loneliness, and empathy as dependent measures. There were statistically significant differences for all variables. Table 1 gives main effects of status group and corresponding estimated means, standard deviations, as well as the results of pairwise comparisons of means effect sizes. For partial eta-squared, an effect size of .01-.06 is interpreted as small, a value of .06-.08 indicates a medium effect, and above .08 a large effect.

Post hoc tests with Bonferroni's correction indicated that, generally, adolescents in the control group showed better emotional adjustment, compared to both rejected and popular groups of aggressive adolescents. In particular, participants in the control group showed lower levels of depressive symptoms and perceived stress, and greater levels of satisfaction with life, compared to aggressive rejected and aggressive popular adolescents. No statistically significant differences were observed between these latter two groups regarding these three variables. Finally, the aggressive rejected adolescents reported more feelings of loneliness and lower empathy, while there were no differences between control and aggressive popular groups. Effect sizes of the differences statistically significant in these individual variables were small in all cases, except for life satisfaction, which was medium.

Family Variables and Sociometric Status Differences

A MANOVA was performed to examine whether there were significant differences in family variables, namely affective cohesion, expressiveness, and family conflict, among adolescents classified as aggressive rejected or aggressive popular, and the control group. There were statistically significant differences on the three variables. Means, standard deviations, results of comparisons of means and effect sizes are presented in Table 2. Follow-up post hoc tests revealed that, generally, those adolescents in the control group reported greater affective cohesion in their families, compared to the two groups of aggressive adolescents, who showed no differences between them. The results are in line with expressivity of opinions and feelings within the family: the scores obtained by the control group were significantly higher than those of either aggressive rejected or aggressive popular adolescents, while these two latter groups did not differ. Differences between groups in affective cohesion and expressiveness showed a medium effect size. Finally, both groups of aggressive adolescents reported higher frequencies of family conflicts than the control group. The effect size for differences in family conflicts was large.

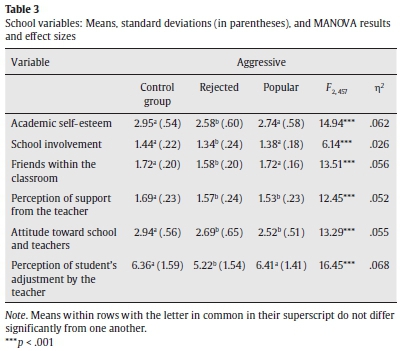

School Variables and Sociometric Status Differences

A MANOVA between the status groups was computed with the following dependent variables: academic self-esteem, school involvement, friends within the classroom, perception of support from the teacher, attitude toward school and teachers, and teacher's perception of student's adjustment. There were significant differences for all variables. As indicated in Table 3, post hoc tests with Bonferroni's correction revealed that aggressive rejected had, generally, the lowest scores on all the school variables. With respect to school tasks, these adolescents reported lower academic self-esteem and lower involvement in classroom activities, compared to the control and aggressive popular groups, there being no significant differences between these latter.

With respect to perception of social relationships in the classroom,aggressive rejected adolescents reported having fewer friends among their classmates, compared to the other two groups. Perception of support from the teacher was lower in both aggressive rejected and aggressive popular adolescents, compared to the control group. The control group had more positive attitudes toward school, teachers and studies compared to the more negative attitudes of both groups of aggressive adolescents. Finally, teachers perceived aggressive rejected students to have greater adjustment problems at school compared to both aggressive popular adolescents the control group.

Effect sizes of the differences statistically significant in these school variables were small in all cases, except for academic self-esteem and teacher's perception of the student's adjustment, which were medium.

Social Variables and Sociometric Status Differences

To test whether aggressive rejected, aggressive popular, and the control group differed with respect to social adjustment, a MANOVA was performed with social self-esteem, group identity, and nonconformist social reputation as dependent measures. There were statistically significant differences on all variables. The main effects of status group, corresponding estimated means, standard deviations, and the results of pairwise comparisons of means and effect sizes are presented in Table 4. Post hoc tests with Bonferroni's correction indicated that aggressive rejected adolescents had the lowest scores for social self-esteem, while there was no difference between control and aggressive popular adolescents. With respect to group identity, the control group had stronger identification with a reference group, compared to both rejected and aggressive popular adolescents. Differences between groups in social self-esteem and group identity showed a medium effect size. Finally, both aggressive rejected and aggressive popular adolescents had higher scores than the control group for nonconformist ideal reputation, this difference having a large effect size.

Discussion

Most of the literature on sociometric status and psychosocial adjustment focuses on the rejected subgroup, traditionally considered as the status at greatest risk for comorbidity of emotional and behavior problems. Far fewer studies have analyzed the psychosocial profile of popular adolescents. Even scarcer are studies addressing the heterogeneity of the popular category, with a very few recent analyses of popularity as a risk factor for deviant behavior in adolescence (Hoff et al., 2009; Mayeux, Sandstrom, & Cillessen, 2008; Rodkin et al., 2000). Moreover, none of these studies examine the profile of aggressive popular students in any depth, with regards to their individual characteristics or the immediate contexts of family and school. Given this state of affairs, the main purpose of the present investigation was to analyze and compare the profiles of adolescents classified respectively as aggressive rejected and aggressive popular.

Differences between Groups in Variables of Individual Adjustment

The previous literature has documented the close relationship between social rejection in adolescence and indicators of emotional maladjustment such as the presence of stress and depressive symptoms (Coie et al., 1992; Kiesner, 2002), feelings of loneliness and low satisfaction with life (Hay et al., 2004; Woodward & Fergusson, 1999). In the present study we found this pattern for aggressive rejected students who, compared to a control group, scored lower on these four variables, indicating greater maladjustment. Aggressive popular adolescents, contrary to the first hypothesis, did not differ from the aggressive rejected group with respect to stress, depression, or dissatisfaction with life. These results extend earlier findings by indicating that accepted and popular students show emotional maladjustment problems, and not just those students who suffer rejection at school. Thus, social acceptance itself does not guarantee emotional adjustment, particularly for those who are also aggressive.

There were, however, significant differences between aggressiverejected and aggressive popular adolescents with respect to empathy and loneliness, the former reporting greater feelings of loneliness than the latter. Previous studies have found that rejected students have smaller networks of friends than average or popular adolescents (Gest et al., 2001; Gifford-Smith & Brownell, 2003; Zettegren, 2005), which may explain the greater loneliness they experience.

Aggressive rejected adolescents had poorer empathic ability than either aggressive popular adolescents or controls. These differences in empathy may be at the root of their lower social acceptance and may also be related to a particular style of aggression. Results of the present study are consistent with those obtained by Gifford-Smith and Brownell (2003), who concluded that aggressive rejected students show a different and particular style of violent behavior, compared to non-rejected students. Aggression that is ineffective predominates in aggressive rejected adolescents; it is reactive, poorly controlled and associated with negative situations experienced as frustrating. In contrast, non-rejected adolescents display effective violence, more active and associated with power, a type of aggression that does not lead to social rejection (Bierman, 2004; Miller-Johnson et al., 2002). Results of the current study suggested that this could be particularly true of aggressive popular students.

Differences between Groups with respect to Family Adjustment

Contrary to the second hypothesis, the results indicate that both aggressive rejected and aggressive popular adolescents had poorer family adjustment than adolescents with average status. Thus, regardless of their level of social acceptance among peers, rejected and popular adolescents with problems of aggression reported greater levels of family conflict than those in the control group, as well as lower levels of affective cohesion and open communication of feelings and opinions among family members. Previous studies have documented a direct association between lack of social capital in the family and at school or, in other terms, between perception of a rejecting and unsupportive family environment, and experience of social rejection in the school (Cava & Musitu, 2000; Ladd, 1999). Likewise, a relationship between negative family climate and children's development of deviant behaviors has been extensively documented (Cummings et al., 2003; Dekovic, Wissink,, & Mejier, 2004; Estévez, Musitu, & Herrero, 2005; Lila, Herrero & Gracia, 2008; Stevens, De Bourdeaudhuij, & Van Oost, 2002).

Results from the current research extend the conclusions of these earlier studies, which either focus on the relations between family variables and sociometric status or between family variables and children's behavioral adjustment. These findings directly confirm the significance of family environment for both aggressive rejected and aggressive popular adolescents; these types did not differ with respect to family adjustment.

Differences between Groups with respect to School Adjustment

Partial support was found for the third hypothesis. Generally, aggressive rejected adolescents had poorer academic and social adjustment at school compared to both aggressive popular adolescents and controls. Thus, as expected, aggressive rejected adolescents reported lower levels of academic self-esteem and academic involvement. These results are consistent with those of previous studies of rejected adolescents (Greenman et al., 2009; Hymel et al., 1993; Jimerson et al., 2009). Nonetheless, findings of the current work add to the picture in showing that popular students who also report aggressive behavior maintain academic self-esteem and school involvement at levels equal to those of average pupils. These results suggest that those at greatest risk of school dropout are rejected students with behavior problems.

The popular aggressive adolescents also received more positive evaluations from their teachers despite their deviant behavior. The results revealed that popular aggressive students had as many friends within the classroom and as positive teacher evaluations as the control group. As hypothesized, aggressive rejected adolescents were perceived as the most maladjusted by teachers and also reported the fewest friends within the classroom. As already mentioned, previous studies have associated popular status with a rich social network (Zettegren, 2005) but our results indicate that positive social evaluations persist for popular status even when this coexists with aggressive behavior. This is of fundamental importance in the design of school interventions, since it helps explain the persistence of deviant behavior of certain students who, being liked and popular among their peers, receive positive feedback for their aggressive behavior, which enhances the probability that such behavior will be repeated.

Finally, and contrary to our a priori expectations, there were two variables that did not differentiate aggressive rejected and aggressive popular students: perception of support from the teacher and attitude toward school and teachers. Attitudes to and evaluations of support at school were more negative in both subgroups than in the control group. Previous studies have shown that students who display negative attitudes toward figures and institutions associated with formal authority, such as teachers and the school context, are more likely to develop aggressive and delinquent behaviors (Emler & Reicher, 1995; Hoge, Andrews, & Lescheid, 1996). Results of the current study extend these previous findings by showing that a negative attitude toward school may be, in fact, a risk factor for aggressive behavior, regardless of the degree of social acceptance among peers.

Differences between Groups with respect to Social Adjustment

Inconsistent with the fourth hypothesis, there was a significant difference between aggressive rejected and aggressive popular adolescents in level of social self-esteem. The lowest scores were recorded for aggressive rejected adolescents, a result in line with their perception of having fewer friends within the classroom and their reported greater experience of loneliness. Previous studies, for example Cava and Musitu (2001), have indicated that those with both popular and average status normally display higher social self-esteem than those with rejected status. This pattern was confirmed in the present study, but with one further variable included in the analysis aggressive behavior. Thus, the results indicated that aggressive behavior on the part of popular adolescents is not incompatible with experiencing positive social interactions. This suggests that aggressive behavior is not by itself as source of greater or lesser social acceptance in the classroom. This is a key consideration in designing interventions focused on achieving the social integration of students at school, since highly conflictive aggressive students may be, at the same time, well-adjusted and adapted to the social dynamics of the classroom.

The results on group identity shed further light on pattern found for social self-esteem. In the light of Gifford-Smith and Brownell's results (2003) on friendships of different sociometric status, it was expected that popular adolescents would identify more strongly with a social reference group than rejected students. The results indicated, however, that both aggressive rejected and aggressive popular students reported feeling less identified with a reference group than average status adolescents; social acceptance by itself does not guarantee stronger group identification. Students who displayed aggressive behavior, even though they were popular, seemed to have friendships of lower quality than those adolescents without behavior problems documented.

Finally, we examined the adolescent's ideal social reputation as a rebellious and nonconformist person. As hypothesized, both aggressive rejected and aggressive popular groups scored significantly higher on this variable than the control group. Both the aggressive subgroups displayed a more obvious and stronger desire to adopt an image of strength and power among their peers, regardless their current level of social acceptance. In line with conclusions from recent studies, there seems to be a close association between the search for social recognition as a non-conformist individual and participation in aggressive acts during adolescence (Buelga, Musitu, Murgui & Pons, 2008; Carroll et al., 1999, 2003; Emler & Reicher, 2005; Moreno, Neves de Jesús, Murgui, & Martínez, 2012). Even though this relationship between nonconformist reputation and aggressive behavior is well supported in previous research, the link between sociometric status and desire to acquire an antisocial reputation among classmates had not previously been examined. Findings of this study are consistent with Emler's (2009) analysis of deviant and delinquent youth in suggesting that aggressive behavior is seen by some adolescents as a strategy to avoid future victimization or rejection, while for others it is interpreted as an opportunity to achieve desired popularity among peers.

Strengths, Limitations, and Implications for Future Research

The present study has several strong points such as: the use of data collecting instruments widely used and validated in previous studies with adolescent samples; a multi-variate approach concurrently examining different domains relating to adolescents' adjustment; the inclusion of a sample of aggressive popular adolescents; and the generation of new findings concerning the similarities and differences between students with aggressive rejected status and those with aggressive popular status. One limitation of this study was the relatively small number adolescents in the subgroup of aggressive popular adolescents (n = 35). A second limitation was that two of the twelve scales used in the current study, perceived stress and classroom environment, had reliabilities between .60 and .70.

A third limitation of this work is its cross-sectional design whichprecludes causal conclusions about observed relationships. For example, we cannot say whether problems of emotional adjustment or negative perception of school were either cause or consequence of students' degree of social acceptance in the classroom - their sociometric status - or of their aggressive behavior. The results obtained in this study are more descriptive than explanatory and mainly concern the different profiles of the two groups examined. Further research examining in more detail the origin and consequences of degree of social acceptance of students with aggressive behavior problems would require the use of a longitudinal design that allows monitoring these adolescents at different points in time. Also, further research could analyze in greater depth sociometric status in relation to the type of violent behavior used by teenagers, which, according to the classification proposed by Gifford-Smith and Brownell (2003), may be categorized into inefficient-useless and efficient-useful. It would be interesting to observe whether there is a significant association between social acceptance, empathic ability, and the specific type of violent behavior shown. These results could shed light on the reasons for rejection or popularity of aggressive students, which would in turn support better interventions.

Implications for Intervention

The results of the current study allow us to conclude that, although aggressive rejected students seem to be at greater risk of maladjustment in several respects compared to adolescents with aggressive popular status (for example, in feelings of loneliness, self-esteem and academic success), both groups require attention for effective interventions addressing school violence and social integration within the classroom. Thus, for instance, both groups had poor emotional adjustment levels - significantly lower than the average group -, indicating we cannot ignore the need for therapeutic work with students who are socially accepted by their peers, but display aggressive behavior. The involvement of families and working with them and the school is another key element in effective intervention, according to the results of the current study. The negative perception of the family environment is a shared feature of aggressive rejected and aggressive popular students since both groups reported the presence of more family conflicts and a poorer family communication than the control group, as pointed out in previous research (Jiménez & Lealle, 2012).

The analysis of school variables also provides indicators for the design of prevention and intervention strategies. It is worth noting that aggressive popular students do not seem to have problems of academic adjustment; their academic involvement is comparable to students with average status and no behavioral problems. It would be advisable, however, to pay more attention to the academic situation of aggressive rejected students to reduce school dropout. The academic success of aggressive popular students, along with the fact that they are supported by their peers and also perceived by teachers as well adjusted within the classroom, makes their identification as a group at risk more difficult. In other words, it is necessary to establish mechanisms in schools that allow the detection of these students, given they normally go unnoticed more often than aggressive rejected students. Intervention could also be helpful to them if aimed at modifying both their behavior and attitudes toward school and teachers.

Attitudes toward teachers and school is another important issue in relation to intervention. The need to work at an attitudinal level is, as suggested by the results of the present study, a key issue for both groups. Aggressive rejected students reported negative attitudes toward teachers and school, but attitudes of aggressive popular students were equally negative, despite their better general academic adjustment. Encouraging positive attitudes, as well as fostering a closer relationship with the teacher - both groups perceived little help from the teacher compared to the average group -, are aspects of remarkable relevance that, according to our findings, would improve the social integration of students and, ultimately, positively influence school life.

Finally, interventions might aim at weakening the link between aggressive behavior and being socially dominant or liked by preventing aggressors from harvesting the benefits of their behavior, as others have also pointed out (Olthof & Goossens, 2008; Olthof, Goossens, Vermande, Aleva, & van der Meulen, 2011). One way of achieving this might involve focusing on aggressors' reputations among their peers. As pointed out by Farmer et al. (2006), the focus of violence prevention programs should extend beyond aggressive adolescents and deviant groups and also address nonaggressive peers who support these behaviors.

The results of the current study indicate that aggressive popular adolescents have friends who admire, respect, and like them. Further research, following the theoretical argument proposed by Emler (2009), could probe further the association between aggressive behavior and the search for a social reputation as a respected, rebellious and nonconformist person, and particularly in the group of aggressive popular students. In order to break down the relationship between these variables, interventions could focus on affecting the attitude of adolescents in a class in such a way that aggressive behavior is no longer perceived as a 'cool' behavior (Rodkin et al., 2006), "but rather as a definitely 'uncool' strategy of someone who cannot think of less aggressive ways to attract attention" (Olthof et al., 2011, p.19). In short, future studies should consider these and other intervention strategies that include all those students at risk of developing adjustment problems, without ignoring socially accepted adolescents who are nonetheless harboring serious problems at other levels.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2005). Amos 6.0 User's Guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc. [ Links ]

Astor, R., Pitner, R.O., Benbenishty, R., & Meyer, H.A. (2002). Public concern and focus on school violence. In L. A. Rapp-Paglicci, A. R. Roberts, &, J. S. Wodarski (Eds.), Handbook of violence (pp. 262-297). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Atienza, F. L., Pons, D., Balaguer, I., & García-Merita, M. (2000). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de satisfacción con la vida en adolescentes. Psicothema, 12, 314-320. [ Links ]

Becker, B. E., & Luthar, S. S. (2007). Peer-perceived admiration and social preference: contextual correlates of positive peer regard among suburban and urban adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 117-144. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00514.x [ Links ]

Bellmore, A. (2011). Peer rejection and unpopularity: Associations with GPAs across the transition to middle school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103, 282-295. doi: 10.1037/a0023312 [ Links ]

Bierman, K. L. (2004). Peer rejection. Developmental processes and intervention strategies. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Bierman, K. L., Smoot, D. L., & Aumiller, K. (1993). Characteristics of aggressive- rejected, aggressive (nonrejected), and rejected (nonaggressive) boys. Child Development, 64, 139-151. doi: 10.2307/1131442 [ Links ]

Birch, S.H., & Ladd, G.W. (1998). Children's interpersonal behaviors and the teacher- child relationship. Developmental Psychology, 34, 934-946. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.934 [ Links ]

Black, B., & Logan, A. (1995). Links between communication patterns in mother-child, father-child, and child-peer interactions and children's social status. Child Development, 66, 255-271. doi: 10.2307/1131204 [ Links ]

Blankemeyer, M., Flannery, D.J., & Vazsonyi, A.T. (2002). The role of aggression and social competence in children's perception of the child-teacher relationship. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 293-304. doi:10.1002/pits.10008 [ Links ]

Brown, M. B., & Forsythe, A. B. (1974). The small sample behavior of some statistics which test the equality of several means. Technometrics, 16, 129-132. doi: 10.2307/1267501 [ Links ]

Bryant, B. K. (1982). An Index of Empathy for Children and Adolescents. Child Development, 53 (2), 413-425. doi: 10.2307/1128984 [ Links ]

Buelga, S., Musitu, G., Murgui, S., & Pons, J. (2008). Reputation, loneliness, satisfaction with life and aggressive behavior in adolescence. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 11, 192-200. [ Links ]

Buhs, E. S., Ladd, G. W., & Herald, S. L. (2006). Peer exclusion and victimization: Processes that mediate the relations between peer group rejection and children's classroom engagement and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 1-13. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.1 [ Links ]

Carroll, A., Hattie, J., Durkin, K., & Houghton, S. (1999). Adolescent reputation enhancement: differentiating delinquent, nondelinquent, and at-risk youths. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 593-606. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00476 [ Links ]

Carroll, A., Green, S., Houghton, S., & Wood, R. (2003). Reputation enhancement and involvement in delinquency among high school students. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 50, 253-273. doi: 10.1080/1034912032000120444 [ Links ]

Carroll, A., Houghton, S., Hattie, J., & Durkin, K. (2001). Reputation enhancing goals: Integrating reputation enhancement and goal setting theory as an explanation of delinquent involvement. In F.H. Columbus (Ed.), Advances in Psychology Research (pp. 101-129). New York: Nova Science Publishers. [ Links ]

Cava, M. J. (2011). Family, teachers, and peers: keys for supporting victims of bullying. Psychosocial Intervention, 20, 183-192. doi: 10.5093/in2011v20n2a6 [ Links ]

Cava, M.J., Buelga, S., Musitu, G., & Herrero, J. (2011). Estructura factorial de la adaptación española de la escala de Identificación Grupal de Tarrant. Psicothema, 23, 772-777. [ Links ]

Cava, M.J., Estévez, E. Buelga, S., & Musitu, G. (2013). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Actitudes hacia la Autoridad Institucional en adolescentes (AAI-A). Anales de Psicología, 29, 540-548. [ Links ]

Cava, M. J., & Musitu, G. (1999). Percepción del profesor y estatus sociométrico en el grupo de iguales. Información Psicológica, 71, 60-65. [ Links ]

Cava, M. J., & Musitu, G. (2000). La potenciación de la autoestima en la escuela. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Cava, M. J., & Musitu, G. (2001). Autoestima y percepción del clima escolar en niños con problemas de integración social en el aula. Revista de Psicología General and Aplicada, 54, 297-311. [ Links ]

Cillessen, A., van Ijzendoom, H., van Lieshout, C., & Hartup, W. (1992). Heterogeneity among peer rejected boys: Subtypes and stabilities. Child Development, 63, 893-905. doi: 10.2307/1131241 [ Links ]

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385-396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [ Links ]

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health (pp. 31-67). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: Across-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557-570. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557 [ Links ]

Coie, J. D., Lochman, J. E., Terry, R., & Hyman, C. (1992). Predicting early adolescent disorder from childhood aggression and peer rejection. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 783-792. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.60.5.783 [ Links ]

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74-101. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.115.1.74 [ Links ]

Cummings, E. M., Goeke-Morey, M., & Papp, L. (2003). Children's responses to everyday marital conflict tactics in the home. Child Development, 74, 1918-1929. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00646.x [ Links ]

Davis, H. (2003). Conceptualizing the role and influence of student-teacher relationships on children's social and cognitive development. Educational Psychologist, 38, 207-234. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3804_2 [ Links ]

Dekovic, M., Wissink, I., & Meijer, A. (2004). The role of family and peer relations in adolescent antisocial behaviour: Comparison of four ethnic groups. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 497-514. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.010 [ Links ]

Deptula, D. P., & Cohen, R. (2004). Aggressive, rejected, and delinquent children and adolescents: a comparison of their friendships. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 75-104. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(02)00117-9 [ Links ]

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [ Links ]

Emler, N. (2009). Delinquents as a minority group: Accidental tourists in forbidden territory or voluntary émigrés? In F. Butera & J. Levine (Eds.), Coping with minority status: Responses to exclusion and inclusion. US: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Emler, N. & Reicher, S. (1995). Adolescence and delinquency: The collective management of reputation. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Emler, N., & Reicher, S. (2005). Delinquency: Cause or consequence of social exclusion? In D. Abrams, M. A. Hogg, & J. M. Marques (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Inclusion and Exclusion (pp. 211-241). New York: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Estell, D. B., Cairns, R. B., Farmer, T. W., & Cairns, B. D. (2002). Aggression in inner-city early elementary classrooms: individual and peer-group configurations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 48, 52-76. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2002.0002 [ Links ]

Estell, D. B., Farmer, T. W., Pearl, R., Van Acker, R., & Rodkin, P. C. (2008). Social status and aggressive and disruptive behavior in girls: individual, group, and classroom influences. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 193-212. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.004 [ Links ]

Estévez, E., Herrero, J., Martínez, B., & Musitu, G. (2006). Aggressive and non-aggressive rejected students: an analysis of their differences. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 387-400. doi: 10.1002/pits.20152 [ Links ]

Estévez, E., Jiménez, T. I., & Moreno, D. (2010). Cuando las víctimas de violencia escolar se convierten en agresores: "¿Quién va a defenderme?". European Journal of Education and Psychology, 3, 177-186. [ Links ]

Estévez, E., Martínez, B., & Jiménez, T. (2009). Las relaciones sociales en la escuela: El problema del rechazo escolar. Psicología Educativa, 15, 5-12. [ Links ]

Estévez, E., Martínez, B., Moreno, D., & Musitu. G. (2006). Relaciones familiares, rechazo entre iguales y violencia escolar. Cultura y Educación, 18, 335-344. doi: 10.1174/113564006779173046 [ Links ]

Estévez, E., Musitu, G., & Herrero, J. (2005). The influence of violent behavior and victimization at school on psychological distress: the role of parents and teachers. Adolescence, 40, 183-196. [ Links ]

Expósito, F., & Moya, M. C. (1999). Soledad and Apoyo Social. Revista de Psicología Social, 2-3, 319-339. doi: 10.1174/021347499760260000 [ Links ]

Farmer, T. W., Leung, M., Pearl, R., Rodkin, P. C., Cadwallader, T. W., & Van Aken, R. (2002). Deviant or diverse peer groups? The peer affiliations of aggressive elementary students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 611-620. doi: 10.1037//0022-0663.94.3.611 [ Links ]

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., & Sierra, B. (1989). Escalas de Clima Social FES, WES, CIES and CES. Madrid: TEA. [ Links ]

Franz, D. Z., & Gross, A. M. (2001). Child sociometric status and parent behaviours. Behavior Modification, 25, 3-20. doi: 10.1177/0145445501251001 [ Links ]

García-Bacete, F. J. (1989). Los niños con dificultades de aprendizaje y ajuste escolar: aplicación y evaluación de un modelo de intervención con padres y niños como coterapeutas (Dissertation). Universitat de València. [ Links ]

Gest, S. D., Graham-Bermann, S. A., & Hartup, W. W. (2001). Peer experience: common and unique features of number of friendships, social network centrality and sociometric status. Social Development, 10, 23-39. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00146 [ Links ]

Gifford-Smith, M. E., & Brownell, C. A. (2003). Childhood peer relationships: social acceptance, friendships, and social network. Journal of School Psychology, 41, 235-284. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(03)00048-7 [ Links ]

Gracia, E., Lila, M., & Musitu, G. (2005). Rechazo parental y ajuste psicológico y social de los hijos. Salud Mental, 28, 73-81. [ Links ]

Graham, S., & Juvonen, J. (2002). Ethnicity, peer harassment, and adjustment in middle school: An exploratory study. Journal of Early Adolescence, 22, 173-199. doi: 10.1177/0272431602022002003 [ Links ]

Greenman, P. S., Schneider, B. H., & Tomada, G. (2009). Stability and change in patterns of peer rejection. School Psychology International, 30, 163-183. [ Links ]

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children's school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72, 625-638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301 [ Links ]

Harrist, A. W., Zaia, A. F., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (1997). Subtypes of social withdrawal in early childhood: Sociometric status and social-cognitive differences across four years. Child Development, 68, 278-294. doi: 10.2307/1131850 [ Links ]

Hay, D. F., Payne, A., & Chadwick, A. (2004). Peer relations in childhood. Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 84-108. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00308.x [ Links ]

Helsen, M., Vollebergh, W., & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 319-335. doi: 10.1023/A:1005121121721 [ Links ]

Herrero, J., & Meneses, J. (2006). Short Web-based versions of the perceived stress (PSS) and Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CESD) Scales: a comparison to pencil and paper responses among Internet users. Computers in Human Behavior, 22, 830-848. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2004.03.007 [ Links ]

Hoff, K. E., Reese-Weber, M., Schneider, W. J., & Stagg, J. W. (2009). The association between high status positions and aggressive behavior in early adolescence. Journal of School Psychology 47, 395-426. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.07.003 [ Links ]

Hoge, R. D., Andrews, D. A., & Leschied, A. W. (1996). An investigation of risk and protective factors in a sample of youthful offenders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Discplines, 37, 419-424. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01422.x [ Links ]

Hymel, S., Bowker, A., & Woody, E. (1993). Aggressive versus withdrawal unpopular children: variations in peer and self-perceptions in multiple domains. Child Development, 64, 879-896. doi: 10.2307/1131224 [ Links ]

Jiang, X. L., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2005). Stability of continuous measures of sociometric status: a meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 25, 1-25. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2004.08.008 [ Links ]

Jiménez, T. I., & Lealle, H. (2012). La violencia escolar entre iguales en alumnos rechazados y populares. Psychosocial Intervention, 21, 77-89. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5093/in2012v21n1a5 [ Links ]

Jimerson, S. R., Durbrow, E. H., & Wagstaff, D. A. (2009). Academic and behaviour associates of peer status for children in a Caribbean community findings from the St Vincent Child Study. School Psychology International, 30, 184-200. [ Links ]

Kiesner, J. (2002). Depressive symptoms in early adolescence: Their relations with classroom problem behavior and peer status. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12, 463-478. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00042 [ Links ]

Koth, C. W., Bradshaw, C. P., & Leaf, P. J. (2008). A multilevel study of predictors of students perceptions of school climate: The effect of classroom-level factors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 96-104. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.96 [ Links ]

Kupersmidt, J. B., Coie, J. D., & Dodge, K. A. (1990). The role of poor peer relationships in the development of disorder. In S. R. Asher & J. D. Coie (Eds.), Peer rejection in childhood (pp. 274-305). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ladd, G. W. (1999). Peer relationships and social competence during early and middle childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 333-359. doi: 10.1146/annurev. psych.50.1.333 [ Links ]

Lila, M., García, F., & Gracia, E. (2007). Perceived paternal and maternal acceptance and childrens outcomes in Colombia. Social Behavior and Personality, 35, 115-124. [ Links ]

Lila, M., Herrero, J., & Gracia, E. (2008). Multiple victimization of Spanish adolescents: A multilevel analysis. Adolescence, 43, 333-350. [ Links ]

Lila, M., Musitu, G., & Buelga, S. (2000). Adolescentes colombianos y españoles: diferencias, similitudes y relaciones entre la socialización familiar, la autoestima y los valores. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 32, 301-319. [ Links ]

Little, T. D., Henrich, C. C., Jones, S. M., & Hawley, P. H. (2003). Disentangling the "whys" from the "whats" of aggressive behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 122-133. doi: 10.1080/01650250244000128 [ Links ]

Maag, J. W., Vasa, S. F., Reid, R., & Torrey, G. K. (1995). Social and behavioral predictors of popular, rejected and average children. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55, 196-205. doi: 10.1177/0013164495055002004 [ Links ]

Mayeux, L., Sandstrom, M. J., & Cillessen, A. (2008). Is Being Popular a Risky Proposition? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 49-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00550.x [ Links ]

Mehrabian, A., & Epstein, N. A. (1972). A measure of emotional empathy. Journal of Personality, 40, 525-543. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1972.tb00078.x [ Links ]

Mestre, V., Pérez-Delgado, E., Frías, D., & Samper, P. (1999). Instrumentos de evaluación de la empatía. In E. Pérez-Delgado & V. Mestre, Psicología moral y crecimiento personal (pp. 181-190). Barcelona: Ariel. [ Links ]

Miller-Johnson, S., Coie, J.D., Maumary-Gremaud, A., & Bierman, K. (2002). Peer rejection and aggression and early starter models of conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal and Child Psychology, 30, 217-230. doi: 10.1023/A:1015198612049 [ Links ]

Moos, R. H., & Moos, B. S. (1981). Family Environment Scale Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press. [ Links ]

Moos, R. H., & Trickett, E. J. (1973). Classroom Environment Scale manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press. [ Links ]

Moreno, D., Estévez, E., Murgui, S., & Musitu, G. (2009). Reputación social y violencia relacional en adolescentes: el rol de la soledad, la autoestima y la satisfacción vital. Psicothema, 21, 537-542. [ Links ]

Moreno, D., Neves de Jesús, S., Murgui, S., & Martínez, B. (2012). Un estudio longitudinal de la reputación social no conformista y la violencia en adolescentes desde la perspectiva de género. Psychosocial Intervention, 21, 67-75. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5093/in2012v21n1a6 [ Links ]

Murray, C., & Greenberg, M. T. (2001). Relationships with teachers and bonds with school: Social-emotional adjustment correlates for children with and without disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 38, 25-41. doi: 10.1002/1520-6807(200101)38:1<25::AID-PITS4>3.0.CO;2-C [ Links ]

Musitu, G., & Cava, M. J. (2001). Familia y educación. Barcelona: Octaedro. [ Links ]