Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychosocial Intervention

versión On-line ISSN 2173-4712versión impresa ISSN 1132-0559

Psychosocial Intervention vol.23 no.3 Madrid dic. 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2014.07.011

Determinants of late diagnosis of HIV infection in Spain

Determinantes del diagnóstico tardío de la infección por VIH en España

María José Fuster-Ruiz de Apodacaa, Fernando Molerob, Encarnación Nouvilasb, Piedad Arazob y David Dalmaub

a Sociedad Española Interdisciplinaria del Sida (SEISIDA), Spain. Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Spain

b Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Spain

This study was funded by the Gilead Sciences Ltd. company.

ABSTRACT

The main goal of this study was to analyse the determinants of late diagnosis of HIV infection. Secondly, we studied the role of the perception of risk and sexual orientation in HIV testing. Twenty-five people with late HIV diagnosis were interviewed. They were contacted through hospitals and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). To design the interview, we integrated the variables considered in the main models of health-related behaviour. We followed a mixed strategy of analysis. Firstly, we carried out thematic analysis of the interviews, followed by quantitative analysis of the initially qualitative data. The results revealed that the most relevant determinants were the appraisal of the threat of HIV and the low perception of HIV risk. Also, the study found many missed opportunities for diagnosis in health-care setting. Low perception of HIV risk was related to unrealistic optimism, low levels of information about HIV, and the presence of stereotypes about people with HIV. High perception of HIV risk was related to strategies to avoid testing. Homosexuals reported a more positive balance between the benefits of knowing their diagnosis and having the disease. The results provide clues that can guide the design of future strategies to promote early diagnosis.

Keywords: HIV. Late diagnosis. Determinants of health behaviour. Qualitative study

RESUMEN

El objetivo principal de este estudio fue analizar los determinantes del diagnóstico tardío de la infección por VIH. Asimismo, se estudió el papel que jugaban en ello la percepción de riesgo y la orientación sexual. Se entrevistó a 25 personas con VIH, con las que se estableció contacto a través de hospitales y de organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONG). Para el diseño del guión de la entrevista se partió de una integración de las variables consideradas en los principales modelos de conductas de salud. Se siguió una estrategia mixta de análisis. Primeramente, se realizó análisis temático de las entrevistas. Seguidamente, se realizaron análisis cuantitativos sobre los datos cualitativos. Se halló que los determinantes más relevantes eran la valoración de amenaza del VIH y la baja percepción de riesgo. Se hallaron también oportunidades perdidas de diagnóstico en el sistema sanitario. La baja percepción de riesgo se asociaba con el optimismo irrealista, la poca información sobre el VIH y los estereotipos sobre las personas con VIH. La alta percepción de riesgo se relacionaba con las estrategias de evitación del test. Los discursos de las personas homosexuales mostraron un balance más positivo de los beneficios de conocer el diagnóstico. Los resultados sugieren claves que pueden guiar el diseño de futuras estrategias de promoción del diagnóstico precoz.

Palabras clave: VIH. Diagnóstico tardío. Determinantes de conductas de salud. Estudio cualitativo

Late diagnosis of HIV infection is a problem in many countries around the world. In Europe, at least 49% of the cases diagnosed had a CD4 count lower than 350/mm3, including 29% of cases with advanced HIV infection (CD4 < 200/mm3) (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [ECDC], 2012). In Spain, where this investigation was carried out, information from the data system of new HIV diagnoses reveals 46% of cases of late diagnosis (Secretaría del Plan Nacional sobre el Sida/Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, 2012). This has serious implications. On the one hand, people who are unaware of their diagnosis cannot benefit from treatment, increasing their risk of morbidity and death (Sobrino-Vegas et al., 2009). On the other hand, the cost of treatment and care of people who are diagnosed late is higher than treatment for people who are diagnosed early (Krentz & Gill, 2011). Lastly, people diagnosed late can infect other people. Research provides data indicating that between 54% and 65% of new infections are caused by people who were unaware of their infection (Cohen, Gay, Kashuba, Blower, & Paxton, 2007).

All these implications indicate the need to study the barriers to early diagnosis in more depth. Testing for HIV is a preventive health behaviour, implying a complex process in which various determinants intervene. Among them are perceived risk and threat, the appraisal of the ability to cope, and beliefs about the opinion of reference persons (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Becker, 1974; Ewart, 1991; Rodríguez-Marín, 2001; Rogers, 1983). The research of the perception of HIV risk has produced diverse results. Thus, some studies found that perception of risk was related to more HIV testing (Kalichman & Hunter, 1993; Maguen, Armistead, & Kalichman, 2000; Myers, Orr, Locker, & Jackson, 1993), whereas others did not find this relationship (Bradley, Tsui, Kidanu, & Gillespie, 2011; Brooks, Lee, Stover, & Barkley, 2011; Catania, Pollack, McDermott, & Qualls, 1990; Dorr, Krueckeberg, Strathman, & Wood, 1999; Goodman & Berecochea, 1994). Other authors have found that, although people at higher risk of HIV had higher rates of HIV testing, increased self-perceived risk was associated with a decreased likelihood of HIV testing intention translating to action (Ostermann, Kumar, Pence, & Wetthen, 2007).

In addition, there are some social and demographic characteristics that influence late diagnosis. Among these are age, being an immigrant, being male, or being heterosexual (Adler, Mounier-Jack, & Coker, 2009; ECDC, 2012; Secretaría del Plan Nacional sobre el Sida/Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, 2012).

Based on the above review, this research had two goals. The first one was to analyse the determinants of late HIV diagnosis in Spain. The second goal was to examine possible differences and similarities in these determinants as a function of HIV risk perception prior to diagnosis and of the participants' sexual orientation. We focused on these two variables for several reasons. On the one hand, in the past, many prevention campaigns by various institutions - both governmental and non-governmental - have emphasized the need to increase people's perception of the risk of infection. However, as already mentioned, the literature found different results regarding the role of perceived HIV risk in early diagnosis. On the other hand, information systems in Europe in general, and in Spain in particular, show that the lowest percentages of late diagnosis are found in men who have sex with men (ECDC, 2012; Secretaría del Plan Nacional sobre el Sida/Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, 2012). Therefore, studying the shared conceptions of these two groups of people (risk self-perceivers versus no-risk self-perceivers, homosexuals versus heterosexuals) could provide important clues to guide the design of future strategies and interventions to promote early diagnosis in different populations.

To achieve these goals, we conducted a qualitative study, interviewing people with late HIV diagnosis. As the theoretical framework to design the study we integrated the variables considered in the main models of health-related behaviour (Rodríguez-Marín, 2001). This framework included the main determinants contemplated in the health belief model (Becker, 1974), the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), and the theory of social action (Ewart, 1991). Qualitative methodology, together with the theoretical approach in data analyses, presented the advantage of enabling us to study the most relevant variables of health-related behaviour from the perspective of the protagonists.

Method

Participants

Participants were 25 people with HIV living in Spain. Participants were selected according to the following criteria: (a) late HIV diagnosis (less than 200 CD4 or AIDS-defining opportunistic infection at the time of diagnosis) and (b) less than five years since diagnosis. The final sample was composed of more than two-thirds of men, predominantly Spaniards, although people with other nationalities also participated. More than one half were heterosexuals, average age was approximately 39 years (Table 1). More than one half had been living with HIV for less than one year.

The Interview

A semi-structured interview was designed. The guideline was assessed by expert judges and pilot tests were carried out (two interviews).

The interview explored the determinants of late diagnosis as well as possible context-related factors of the participants. Figure 1 presents the series of variables that were considered in the interview guideline. This included two initial general questions ("Can you tell me, how was your diagnosis, that is, why you took the test, or what prompted you to be tested for HIV?" "Why do you think you didn't get tested before, as a consequence of which you were diagnosed late?" ) On the basis of these questions, we explored in depth the variables shown in Figure 1, depending on the person's discourse and experience with the HIV test.

The interview also explored other factors of the context prior to the participants' diagnosis: high-risk practices for contraction of HIV, knowledge about HIV, prior experience with HIV testing, proximity to people with HIV, and social support.

Procedure

The participants were selected by professional members of the research team of this study who worked in health-care units for people with HIV or in NGOs. These professionals informed the selected people about the goals of the study, requesting their participation and collecting their informed consent. None of the participants approached refused to participate in the study. Next, they were requested to provide a telephone number and an email address. We then contacted them to schedule the interview. The interviews were carried out in offices of the centres where the participants had been recruited. The interview had an average duration of one hour and was performed by an investigator with expert psychosocial training in the target area of the study. This researcher was a female. At the beginning of the interview, participants' permission to audio-record the interview was requested, after ensuring them of the confidentiality of their data. The files were assigned an identification code to maintain anonymity.

Data Analysis

To address the goals proposed in this research, we performed a mixed strategy of analysis.

Firstly, qualitative analysis was carried out through thematic analysis of the interviews (Braun & Clarke, 1994). For this purpose, the interviews were transcribed literally and coded. This process allowed us to rate the information saturation, that is, the point at which no new categories emerged during the process of theory development and at which, therefore, the research questions had been answered (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Subsequently, the codes were grouped into categories, which were formed through the theory-driven approach. Thus, we linked the categories to determinants of health behaviour (see Figure 1). This process was done by consensus of all the members of the research team.

Next, we performed quantitative analysis of the initially qualitative data (Boyatzis, 1998; Ryan & Bernard, 2000). For this purpose, firstly, the frequencies of each category were counted. This analysis was submitted to inter-judge control. Cohen's mean kappa index of agreement was .76, indicating good reliability (Landis & Koch, 1977). Any inconsistencies among judges were resolved by consensus. Next, we carried out correspondence factor analysis (CFA) to analyse the discourse system as a function of perceived HIV risk and sexual orientation. For this purpose, we introduced as active modalities (column category) the categories that had shown some variability and as illustrative modalities (row category) the groups of people classified as a function of the two variables of analysis (prior perceived HIV risk and sexual orientation). To interpret the factor axes, the highest contributions of the categories had to exceed the mean (100/nr. of active modalities). We used the SPAD-T statistical package (Lebart & Salem, 1994).

Results

The results are presented as a function of the goals of the research. Firstly, the most relevant determinants of late diagnosis found in the thematic analysis are described. Table 2 presents all the themes found and their link to the determinants of health behaviour analyzed in this study. Secondly, we present the articulate discourse system as a function of interviewees' perceived HIV risk and sexual orientation found through CFA.

Determinants of HIV Testing: Results of the Thematic Analysis

Perceived risk and threat. Many of the participants stated that they did not perceive risk of HIV prior to diagnosis. The reasons for this are mainly related to two factors: on the one hand, unrealistic optimism, associated with ignorance and the stereotyped conception of the infection; on the other, their affirmation of having had a history of few risk practices or of having had unprotected sex only with their long-term partner.

You really thought it would never happen to you. It's as though it were a disease that, until you know a bit more about it, you think it's something that only happens to people who go to whorehouses or inject drugs. And since I don't inject drugs… (Male, 42 years old)

We also found people who did perceive they were at risk of HIV. This perception was associated with the awareness of having practised risky sex or of having had sexual relations with a person with a sexually transmitted disease (STD) or actual or suspected HIV.

Yes, I was scared I might be infected. There was one very special boy... I was really in love with him. I was scared he might have something... In my circle, they always commented that this person might be infected. (Female, 35 years old)

With regard to the interviewees' beliefs about HIV infection, we found a generalized representation of a threatening disease. Two types of threats were indicated. On the one hand, there was the perceived severity of the disease, which was associated with death and ignorance about the clinical advances in its treatment. On the other hand, we found a representation of a stigmatized and stereotyped disease.

I thought it was a super-remote disease that had nothing to do with me or with the world we live in; I thought it was more typical of Africa or Asia, of some other kind of culture… that, although it does exist here, it's more to do with drug addicts... with homosexual couples' relationships… (Female, 29 years old)

Appraisal of coping abilities. The interview also explored peoples' appraisal of their ability to cope with the results of a positive HIV test. This part of the interview targeted the people who had gone through decision stages about HIV testing and also those who had had some time in which to think of the possibility of being infected before they received the diagnosis.

Most of the interviewees did not perceive self-efficacy to cope with being tested and receiving the diagnosis. The cost-benefit balance of knowing the diagnosis was in favour of the costs. These were the threat of stigma, fear of the disease, and the threat to their self-concept.

Before I received the diagnosis, I was nervous, anxious, fearful... What was most important for me was my own self, I don't know, it was as though I felt dirty, for having been infected with something that I thought had nothing to do with me. Then, that feeling of being dirty, well, the truth is that it's very harmful… Besides, I thought I would never have anyone by my side. (Male, 36 years old)

Some of these people reported having coped with the situation by means of avoidance strategies such as not going to pick up the result or not carrying out the medical follow-up after the initial diagnosis. In all these cases, they tried to suppress or distance themselves psychologically from the fact of being infected with HIV. In these people, the signal to finally go to the health-care system was their worsening health status, the influence of a reference person from their family environment or friends, or having had a sexual partner with some STD or actual or suspected HIV.

They told me I might have it, that I had to come back for the confirmation test. Then I really got scared... I just couldn't. I didn't go back. So, some time went by, I tried to get used to the idea, but I couldn't conceive of having HIV. Until I finally started to feel bad... I used to look at myself in the mirror and even I was scared at what I saw. I was in shock. And my mother sent me to the doctor… (Male, 24 years old)

Nevertheless, some people also indicated some benefits of testing for HIV, among them the possibility of controlling the infection through treatment, anxiety reduction, or being able to prevent transmission to their loved ones.

When I did the test, I thought it was like the definite test. It took a load off my mind, I would know whether I had it or not. And everything started there. If I had it, I had to act accordingly, and the same if I didn't have it. (Male, 22 years old)

Beliefs about the opinion of reference persons (normative beliefs). Most interviewees anticipated stigma or suffering in their families or social environment. These people did not share the moment of diagnosis with their friends or relatives and they continued to conceal their condition of being a person with HIV at the time of the interview.

In my social circle, they don't even mention it. I thought it had to do with being in a circle of conservative people. Because, in my former circle, you couldn't say anything about this... Something happened with a friend, we were together and I don't know why, or with regard to what he said something about "sidoso" [a derogatory term for someone with AIDS]. Man, I was really offended! (Male, 36 years). In my family environment I never told them I had done the test and I have never commented on it. My sister is going through a really shitty and violent divorce, my mother is 78 years old. What's the point? It seems ridiculous to tell them, why distress them so badly when it's not necessary? (Male, 50 years old)

HIV testing: Context and signal for action. Most of the interviewees had had no previous history of HIV testing and they had never thought about testing, so they were in the prior stages to deciding about this health behaviour. Many reported that they had gone to the health-care system because of poor health status, without attributing their symptoms to HIV. In most of these cases, the primary care professionals and/or specialized professionals who attended to them did not attribute their symptoms to HIV and did not request them to test for HIV. Many of the interviewees were diagnosed upon admittance to hospital due to a severe disease and/ or to an AIDS-defining disease. In general, the participants reported several follow-up visits, with up to four years of missed opportunities for diagnosis.

I went to the doctors for four years. In the mornings, I couldn't walk well... In the emergency ward, they thought it was a problem with my back. They did a magnetic resonance and told me I had hernias, and I should take anti-inflammatory drugs. Later, I could not walk... and also my arms... they did a magnetic resonance of my head. The doctor told me I had a brain tumour and I would only live for six months. They sent me to a neurologist and he said I had to be operated on... They removed the tumour... Later in the hospital, the doctor told me: we have the results of the analysis of the tumour, it's a toxoplasmosis... Right away, he tested me for HIV… all those years I was going to the doctor, none of them thought that I had AIDS, because I don't look like a person with AIDS. (Female, 53 years old)

Some people, however, did have the intention or had decided to test for HIV. In some of these cases, the signal was having had sexual relations with a person who they knew or suspected had HIV or some other sexually transmitted infection. In other cases, what drove them to make the decision to be tested was the influence of a reference person (partner, family and/or friend).

… I went to be tested with a friend because we had both been with the same fellow... We had heard, some time ago, that he had been a transsexual's pimp or something like that. And he was sleeping with him. And when we found out, we were in a state of shock and we went to be tested... (Male, 27 years old)

Articulate Discourse System as a Function of Interviewees' Perceived HIV Risk and Sexual Orientation: Results of the Correspondence Factor Analysis (CFA)

In order to address the second goal of this investigation, that of analyzing the articulate discourse system as a function of interviewees' perceived HIV risk and sexual orientation, we carried out CFA.

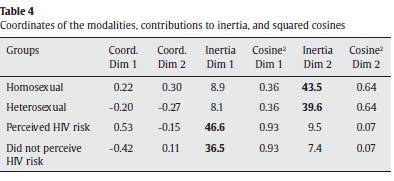

The first factorial axis, which presented 73.12% of cumulative inertia trace, was defined at its positive pole by 16 modalities and at its negative pole by 12 modalities. These modalities presented a contribution higher than the mean (1.53) and a relative contribution of the factor to the modalities ranging between 37% and 100% (Table 3). The group of people who perceived HIV risk prior to their diagnosis was positively related to this factorial axis and those who did not perceive HIV risk were negatively related to it (Table 4).

The second factorial axis, which presented 26.88% of cumulative inertia trace, was defined by 19 modalities that presented a contribution higher than the mean and a relative contribution of the factor to the modality ranging between 21% and 92% (Table 3). Ten of the modalities defined the positive pole and nine defined the negative pole. The group of homosexuals was positively related to this factorial axis and the group of heterosexuals was negatively related to it (Table 4). Figure 2 presents the CFA and the projection of the groups onto the factorial space.

Articulate discourse system as a function of perceived HIV risk. The discourse of the people who perceived HIV risk was at the positive pole of the first factor. At some time, they had thought about testing for HIV and were at the decision stage in this regard. With regard to their health status, they frequently presented mild symptoms at the time of diagnosis. The reason for their perception of HIV risk perception was their awareness of having frequently practised unprotected sex and having engaged in sexual relations with people with STD or actual or suspected HIV. These people were more knowledgeable about HIV infection and about the clinical advances in treatment. In general, their appraisal of their coping ability was negative; they felt incapable of facing either the test itself or the diagnosis, as they believed there were more costs than benefits to being tested. These people's appraisal of the threat of HIV focused on health, self-concept, and their anticipation of stigma among their reference persons. They reported having engaged in avoidant coping strategies, either of testing or of picking up the results of the test. We denominate the pole of this factorial axis awareness of HIV risk, anticipation of stigma and avoidant coping.

The discourse of those who did not perceive HIV risk prior to diagnosis was at the negative pole of this first factorial axis. There was a predominance of women in this group. These people were at the prior stages of deciding to test for HIV and had therefore never previously considered testing. In this group, the missed opportunities for diagnosis in the health-care system seemed to be related to doctors' erroneous assumptions about their risk of contracting HIV. These people apparently had little information about HIV infection. They were unaware of the advances in treatment of HIV and of how to prevent it. In general, they stated that they had engaged in unprotected sex infrequently or that they had only had sex with their long-term partner. This, along with unrealistic optimism, their little knowledge about the infection, and the presence of stereotypes about people with HIV determined their non-risk HIV perception. This group was unfamiliar with the infection and socially remote from people with HIV. We denominated this pole lack of awareness of HIV risk and of HIV knowledge, stereotyped view and unrealistic optimism.

Articulate discourse system as a function of sexual orientation. At the positive pole of the second factorial axis, where homosexually oriented people were located, there was a predominance of youths. This group was at decision-making stages with regard to testing for HIV. Their perceived good-health status, their reporting having carried out few HIV-risk behaviours, and the presence of stereotypes attenuated their perception of HIV risk. These people anticipated support from their reference persons and, in fact, they had received support from friends when undergoing the test and after receiving the diagnosis. In general, they considered that testing for HIV was a positive action, indicating that the greatest risk was the threat to their self-concept. We denominated this pole positive valuation of HIV testing, approach coping and social support.

At the negative pole, where heterosexuals were located, there were more women. In this group, there were two diagnostic contexts. In one of them, they had missed opportunities for diagnosis by not requesting the doctors to do the test, even in the presence of suggestive symptoms, and in the other context, the doctors requested them to test because of their partner's diagnosis. In the men of this group, the infection pathway was mainly through sharing injection material. In the cases in which they perceived HIV risk, it was related to their proximity to people with HIV in their environment. This group reported having received family support after receiving the diagnosis. We denominated this pole lack of identification of women's HIV symptoms, HIV-risk perception, and diagnosis due proximity to people with HIV.

Discussion

The results of this study have served to clarify the most relevant determinants of HIV testing and to understand the barriers that contribute to late diagnosis of HIV infection. Furthermore, this study contributes knowledge about an issue that prior research had not resolved, namely, the role of perceived risk in testing or not testing for HIV. Additionally, the study contributes to our understanding the association of some variables with the low incidence of late diagnosis in homosexual men. These aspects are commented on below.

This study found that important determinants to late diagnosis were the interviewees' beliefs about HIV, particularly their appraisals of threat and their low self-perception of HIV risk.

With regard to the appraisal of threat, we found that it was made up of the perception of the severity or seriousness of the infection and the associated stigma. Information linking HIV to punishable behaviours and stereotypes continues to be pervasive. In addition to having a personal representation of the infection as a stigmatized disease, the interviewees anticipated being the victims of rejection by their reference people. Threat of stigma and fear of the disease as barriers for early diagnosis had already been found in previous studies (Delva et al., 2008; Forsyth et al., 2008; Hoyos et al., 2013; Sambisa, Curtis, & Mishra, 2010; Stolte et al., 2007).

With regard to the perception of HIV risk, as mentioned before, previous research had found divergent results about its role in early diagnosis (Bradley et al., 2011; Brooks et al., 2011; Catania et al., 1990; Dorr et al., 1999; Goodman & Berecochea, 1994; Kalichman & Hunter, 1993; Maguen et al., 2000; Myers et al., 1993; Ostermann et al., 2007). Therefore, in this study, we compared the discourse of the interviewees as a function of their prior self-perception of HIV risk. The results showed that the discourse of people with a low perception of HIV risk was associated with unrealistic optimism; that is, thinking that one is less likely than the average person to suffer from undesirable events (Weinstein, 1980). There are two relevant factors that influence this optimism. Firstly, there is the fact that the more severe the disease, the more convinced people become that their possibilities of becoming infected are lower than those of a similar person. Secondly, if people hold stereotypes about the type of individual who acquires the disease, they use them to defend their identity, so they rarely consider themselves to be representative of that prototype (Weinstein, 1980). It has been observed that both severity and stereotypes were included in these people's representation of HIV, and this could have influenced their unrealistic optimism and, as a consequence, their low perception of HIV risk. Moreover, these people had little knowledge of and were socially remote from HIV infection.

The results showed that perceiving HIV risk did not determine greater frequency of testing for HIV. This result is consistent with the studies which found that perception of HIV risk was not related to more HIV testing (Bradley et al., 2011; Brooks et al., 2011; Catania et al., 1990; Dorr et al., 1999; Goodman & Berecochea, 1994; Ostermann et al., 2007). The articulate discourse system shown by the CFA contributed to our knowledge of the variables that can explain this result. For instance, it was observed that people who perceived HIV risk rated the threat of HIV as higher than their appraisal of their coping ability, leading to avoidance behaviours that determined late diagnosis. For these people, HIV not only constituted a big threat due to social stigmatization and the severity of the disease, but also they did not perceive themselves as being able to cope with the fact of having the disease. This explanation is coherent with the study of Stolte et al. (2007), who found that fear, not wanting to know, and not feeling able to cope with a positive test result were reasons for not testing in people with unknown HIV serology.

The importance for early diagnosis of the positive appraisal of coping and of the results of the behaviour of testing is also observed when analyzing people's discourse according to their sexual orientation. This, along with greater proximity to people with HIV and more social support, differentiated the discourse of homosexual people from that of heterosexuals. According to the literature, the belief that there are more advantages than disadvantages to the behaviour, and normative beliefs, or the opinion of reference persons, are important predictors of health-related behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). Hence, these differences found may be contributing to fewer late diagnoses in homosexual men. In fact, some studies in Spain have shown that men who only had sex with men had tested for HIV more frequently than heterosexuals (Belza et al., 2014) and also that this collective held positive attitudes towards HIV prevention programs (Fernández-Dávila, Lupiañez-Villanueva, & Zaragoza-Lorca, 2012).

Lastly, in addition to the interviewees' attitudes and beliefs, this study also found that there were barriers to early diagnosis in the health-care system. Many missed opportunities for diagnosis were found, especially in the group of people who reported not perceive HIV risk prior to their diagnosis. According to these people, the doctors who attended to them did not attribute their symptoms to HIV until a severe AIDS-defining disease appeared. The existing research had already identified this barrier (Deblonde et al., 2010), showing various obstacles that are obstructing early diagnosis. On the one hand, there seems to be some anxiety component in clinical staff with little experience in dealing with this infection that determines attitudes of inhibition or avoidance of mentioning HIV (Burns et al., 2008). On the other hand, some professionals seem to make erroneous assumptions about the patient's risk of HIV (Liddicoat et al., 2004). Lastly, some studies have found that health professionals admitted that they lack training to deal with this infection (Stokes, McMaster, & Ismail, 2007). These obstacles can lead to the fact that health professionals' not offering to test patients may become an important reason for not testing and, as a result, for late diagnosis (Kwapong, Boateng, Agyei-Baffour, & Addy, 2014).

The results of this study have important implications for the design of psychosocial interventions to help to reduce late diagnosis. From them, it is concluded that it is necessary for these interventions to focus on reducing the sense of threat of HIV, that is, the perception of the severity of the disease and of stigma. With regard to the perception of HIV risk, we must question interventions that only promote it without reducing the perception of severity and stigma or stimulating people's appraisal of their ability to cope. Moreover, promoting a more positive perception of the cost-benefit balance of testing should be an essential element. This leads us theoretically to the Motivation Model of protection (Rogers, 1983), according to which an adaptive or maladaptive response to a threat to health is explained as a function of the appraisal of the threat and the appraisal of one's coping ability. Interventions should be designed taking into account the target collective's characteristics, beliefs, and situation with regard to HIV testing, and the determinants and barriers that can affect them differentially should be underlined.

Similarly, interventions aimed at training and preparing health professionals are also necessary.

This study presents an essential limitation: it is a retrospective analysis. This type of study can find that the interviewees' beliefs have adapted after receiving the diagnosis. Thus, it is necessary to carry out future investigations, both with the general population and with the most vulnerable groups of people who are not diagnosed with HIV.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the people with HIV for their participation, as well as the doctors and collaborators from NGOs who helped with the selection of the participants.

References

Adler, A., Mounier-Jack, S., & Coker, R. J. (2009). Late diagnosis of HIV in Europe: Definitional and public health challenges. AIDS Care, 21, 284-293. doi: 10.1080/09540120802183537 [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50, 179-211. doi: 10.10116/0749-5978(91)90020-T [ Links ]

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Becker, M. H. (1974). The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Education Monographs, 2, 409-419. [ Links ]

Belza, M. J., Figueroa, C., Rosales-Statkus, M. E., Ruiz, M., Vallejo, F., & Fuente, L. D. L. (2014). Low knowledge and anecdotal use of unauthorized online HIV self-test kits among attendees at a street-based HIV rapid testing programme in Spain. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 25, 196-200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.03.1379 [ Links ]

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, London, & New Delhi: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Bradley, H., Tsui, A., Kidanu, A., & Gillespie, D. (2011). Client characteristics and HIV risk associated with repeat HIV testing among women in Ethiopia. AIDS and Behavior, 15, 725-733. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9765-1 [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3, 77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Brooks, R. A., Lee, S. J., Stover, G. N., & Barkley, T. W. (2011). HIV testing, perceived vulnerability and correlates of HIV sexual risk behaviours of Latino and African American young male gang members. International journal of STD & AIDS, 22, 19-24. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010178 [ Links ]

Burns, F. M., Johnson, A. M., Nazroo, J., Ainsworth, J., Anderson, J., Fakoya, A., ... Fenton, K. A. (2008). Missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis within primary and secondary healthcare settings in the UK. Aids, 22, 115-122. doi: 10.1097/ QAD.0b013e3282f1d4b6 [ Links ]

Catania, J. A., Pollack, L., McDermott, L. J., & Qualls, S. H. (1990). Help-seeking behaviors of people with sexual problems. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 19, 235-250. doi: 10.1007/BF01541549 [ Links ]

Cohen, M. S., Gay, C., Kashuba, A. D., Blower, S., & Paxton, L. (2007). Narrative review: Antiretroviral therapy to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV-1. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146, 591-601. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00010 [ Links ]

Deblonde, J., De Koker, P., Hamers, F. F., Fontaine, J., Luchters, S., & Temmerman, M. (2010). Barriers to HIV testing in Europe: A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health, 20, 422-432. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp231 [ Links ]

Delva, W., Wuillaume, F., Vansteelandt, S., Claeys, P., Verstraelen, H., Broeck, D. V., & Temmerman, M. (2008). HIV testing and sexually transmitted infection care among sexually active youth in the Balkans. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 22, 817-821. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0237 [ Links ]

Dorr, N., Krueckeberg, S., Strathman, A., & Wood, M. D. (1999). Psychosocial correlates of voluntary HIV antibody testing in college students. AIDS Education and Prevention, 11, 14-27. [ Links ]

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [ECDC]/WHO Regional Office for Europe (2012). HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2011. Stockholm: Author. Retrieved from http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/20121130-Annual-HIVSurveillance-Report.pdf [ Links ]

Ewart, C. K. (1991). Social Action Theory for a Public Health Psychology. American Psychologist, 46, 931-946. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.9.931 [ Links ]

Fernández-Dávila, P., Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., & Zaragoza Lorca, K. (2012). Actitudes hacia los programas de prevención on-line del VIH y las ITS y perfil de los usuarios de Internet en los hombres que tienen sexo con hombres. Gaceta Sanitaria, 26, 123-130. [ Links ]

Forsyth, S. F., Agogo, E. A., Lau, L., Jungmann, E., Man, S., Edwards, S. G., & Robinson, A. J. (2008). Would offering rapid point-of-care testing or non-invasive methods improve uptake of HIV testing among high-risk genitourinary medicine clinic attendees? A patient perspective. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 19, 550-552. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008141 [ Links ]

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Goodman, E., & Berecochea, J. E. (1994). Predictors of HIV testing among runaway and homeless adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 15, 566-572. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)90140-X [ Links ]

Hoyos, J., Belza, M. J., Fernández-Balbuena, S., Rosales-Statkus, M. E., Pulido, J., & de la Fuente, L. (2013). Preferred HIV testing services and programme characteristics among clients of a rapid HIV testing programme. BMC public health, 13(1), 1-9. [ Links ]

Kalichman, S. C., & Hunter, T. L. (1993). HIV-related risk and antibody testing: An urban community survey. AIDS Education and Prevention, 5, 234-243. [ Links ]

Krentz, H. B., & Gill, M. J. (2011). The direct medical costs of late presentation (< 350/ mm3) of HIV infection over a 15-year period. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2012, 1-8. [ Links ]

Kwapong, G. D., Boateng, D., Agyei-Baffour, P., & Addy, E. A. (2014). Health service barriers to HIV testing and counseling among pregnant women attending ANC; a cross-sectional study. BMC health services research, 14, 267. [ Links ]

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 159-174. doi: 10.2307/2529310 [ Links ]

Lebart, L., & Salem, A. (1994). Statistique textuelle. Paris: Dunod. [ Links ]

Liddicoat, R. V., Horton, N. J., Urban, R., Maier, E., Christiansen, D., & Samet, J. H. (2004). Assessing missed opportunities for HIV testing in medical settings. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19, 349-356. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21251.x [ Links ]

Maguen, S., Armistead, L. P., & Kalichman, S. (2000). Predictors of HIV antibody testing among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 252-257. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00078-6 [ Links ]

Myers, T., Orr, K. W., Locker, D., & Jackson, E. A. (1993). Factors affecting gay and bisexual men's decisions and intentions to seek HIV testing. American Journal of Public Health, 83, 701-704. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.83.5.701 [ Links ]

Ostermann, J., Kumar, V., Pence, B. W., & Whetten, K. (2007). Trends in HIV testing and differences between planned and actual testing in the United States, 2000-2005. Archives of internal medicine, 167, 2128-2135. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2128 [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Marín, J. (2001). Psicología social de la salud [Social psychology of health]. Madrid: Síntesis. [ Links ]

Rogers, R. W. (1983). Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In J. T. Cacioppo & R. E. Petty, Social Psychophysiology (pp. 153-176). New York, NY: Guilford. [ Links ]

Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2000). Data management and analysis methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2 Edition, pp. 769-802). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Sambisa, W., Curtis, S., & Mishra, V. (2010). AIDS stigma as an obstacle to uptake of HIV testing: Evidence from a Zimbabwean national population-based survey. AIDS Care, 22, 170-186. doi: 10.1080/09540120903038374 [ Links ]

Secretaría del Plan Nacional sobre el Sida/Centro Nacional de Epidemiología. Área de Vigilancia y Conductas de Riesgo ( 2012). Vigilancia epidemiológica del VIH/Sida en España: Sistema de información sobre nuevos diagnósticos de VIH y registro nacional de casos de Sida [Epidemiologic surveillance of HIV/AIDS in Spain: Information System of new diagnoses of HIV and national registration of AIDS cases]. Madrid: Author. Retrieved from http://www.msc.es/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfTransmisibles/sida/vigilancia/InformeVIHsida_Junio2012.pdf [ Links ]

Sobrino-Vegas, P., Miguel, L. G. S., Caro-Murillo, A. M., Miró, J. M., Viciana, P., Tural, C., ... Moreno, S. (2009). Delayed diagnosis of HIV infection in a multicenter cohort: Prevalence, risk factors, response to HAART and impact on mortality. Current HIV Research, 7, 224-230. doi: 10.2174/157016209787581535 [ Links ]

Stokes, S. H., McMaster, P., & Ismail, K. M. (2007). Acceptability of perinatal rapid point-of-care HIV testing in an area of low HIV prevalence in the UK. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 92, 505-508. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.106070 [ Links ]

Stolte, I. G., de Wit, J. B., Kolader, M. E., Fennema, H. S., Coutinho, R. A., & Dukers, N. H. (2007). Low HIV-testing rates among younger high-risk homosexual men in Amsterdam. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 83, 387-391. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019133 [ Links ]

Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 806-820. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

e-mail: mjfuster@psi.uned.es

Manuscript received: 06/03/2014

Accepted: 23/07/2014