Introduction

In most industrialized societies, including Denmark where the current study was conducted, the divorce rate exceeds 40% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016; European Commission, 2015; Statistics Denmark, 2017). Divorce has consistently been found to be among the most stressful life events and is often perceived as a prolonged stressful situation by divorcees (Dohrenwend et al., 1978; Freeman et al., 2008; Hobson & Delunas, 2001). Experiencing a stressful life event and prolonged exposure to stressful situations are associated with an increased risk of illness and poorer overall physical and mental health. This includes bodily distress syndrome, increased depression and anxiety symptoms, unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking and physical inactivity, and reduced social interaction and support (Budtz-Lilly et al., 2015; Cohen et al., 1997; Danese & McEwen, 2012; Fink & Rosendal, 2015; Kessing et al., 2003; Nielsen et al., 2014; Sutin et al., 2010).

Psychological stress refers to an individual's evaluation of environmental experiences as threatening, excessively demanding, and/or potentially harmful coupled with the perception of inadequate abilities to cope with the experience (Allen et al., 2014; Cohen et al., 1997). Perceived stress refers to the degree to which people find their lives or specific (life) events stressful, appraises one's situation as unpredictable, and feel unable to manage day-to-day challenges and that one's problems keep piling up (Cohen et al., 1983; Dissing et al., 2019).

Although divorce is considered one of the most stressful life events, researchers and theorists highlight the importance of coping processes when studying the impact of these events on stress responses (Cohen et al., 1983). Therefore, this study focuses on perceived stress by assessing the experienced level of stress as a function of an objective stressful event (in this case, divorce) and coping processes (here, the coping skills obtained through the study intervention tested; Cohen et al., 1983).

In Denmark, where the current study was conducted, divorcees report the highest levels of perceived stress when compared to their continuously married, widowed, or single counterparts (Nielsen et al., 2008). This indicates that although adverse effects of divorce, such as stress, may be sensitive to a 'time heals' effect (Hald et al., in press; Thuen, 2001), whereby perceived stress naturally declining over time, to many divorcees post-divorce life remains stressful (Amato, 2014; Booth & Amato, 1991; Strohschein, 2005). This may be due to co-parenting, fewer financial resources, change of living condition, altered social status, loss of social support, and (eventually) new partners and new family members with stepfamilies being introduced (e.g., Kołodziej-Zaleska & Przybyła-Basista, 2016; Leopold, 2018; Perrig-Chiello et al., 2015). Accordingly, the development and effect testing of interventions which targets the divorcee's experience of stress over time is of public health relevance especially considering that prolonged levels of high stress can detrimentally affect health-related outcomes and be a significant financial burden to society (Budtz-Lilly et al., 2015; Fink & Rosendal, 2015).

The majority of divorce-related intervention programs have focused on children, divorce conflict, and co-parenting skills as the outcomes (Boring et al., 2015; Greenberg et al., 2019; Klein Velderman et al., 2018; McIntosh & Tan, 2017; Pelleboer-Gunnink et al., 2015; Sandler et al., 2018). Those that have targeted adults typically focus on depression or post-divorce adjustment as the outcomes in intervention assessment (e.g. Apraiz et al., 2015; Brodbeck et al., 2017; Yárnoz et al., 2008).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published longitudinal RCT studies on the effectiveness of online interventions in reducing perceived stress among recently divorced adults. In this connection, researchers, health care professionals, public policymakers, and other stakeholders have highlighted both the need for and lack of research and evidence-based online interventions for adults and children experiencing divorce, particularly scalable cost-effective online interventions. Online interventions have the potential to improve availability, and often have greater convenience of use, equity, and cost-effectiveness than more traditional face-to-face interventions (Amato, 2000; Bowers et al., 2011, 2014; Dennis & Ebata, 2005; Eysenbach et al., 2011; Schramm & McCaulley, 2012).

To address this gap in knowledge, our study presents the results of a one-year longitudinal RCT digital intervention called 'Cooperation after Divorce' (CAD), focusing on the reduction of perceived stress levels among recently divorced individuals.

Specifically, we hypothesize and investigate the following:

Hypothesis 1: The CAD digital intervention will significantly decrease self-perceived stress among divorcees over a one-year period.

Research question 1: At the one-year follow-up, how will self-perceived stress levels be in the intervention and control group, respectively, compare with those of the Danish background population?

Method

Participants

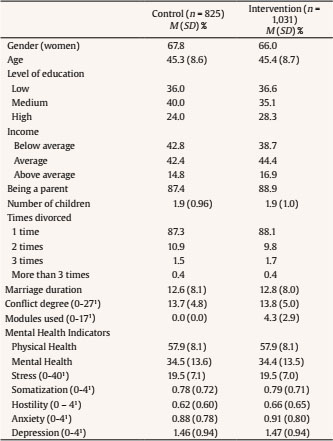

A total of 1,856 recently divorced Danish residents (66.8% women) completed the baseline survey on average 4.74 days (SD = 7.10 days) after they obtained their juridical divorce and entered the present study. The average age of participants was 45.32 years (SD = 8.66). On average, participants had been married 12.74 years (SD = 8.03) before their divorce and for almost 88% of participants this was their first divorce. Most of the sample reported to have children (88.3%) with an average of 1.88 child (SD = 0.99) per participant. On average, children were13.50 years of age (SD = 8.16) at the time of divorce. For further sample description, please see Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Sample Characteristics of Recently Divorced Danes

NoteThere were no significant between groups differences.

1Possible value range.

Response rates. Participants were recruited through an e-mail invitation along with the official divorce decree, which was sent by the Danish State Administration (DSA). As the DSA was not able to provide an exact number of survey links distributed during the study inclusion period (January 2016 to January 2018), the exact response rates cannot be calculated. Of the 1,882 individuals who agreed to participate in the study, 1,856 (98.6%) completed the baseline questionnaire and comprised the final analytical sample (see also Figure 1).

Representativeness of the study sample. To assess possible response bias, the study sample was compared to national population data for all people who divorced in Denmark during the study period obtained from Statistics Denmark. The study sample was representative in terms of age, income, and marriage duration, but included more female participants, c2(1, n = 1,856) = 208.45, p < .001, more highly educated individuals, c2(2, n = 1,856) = 1135.23, p < .001, and individuals with fewer previous divorces, t(1855) = -8.47, p < .001 compared with the background population of divorcees.

Randomization bias. Randomization was conducted by the system on a two-week sequential interval schedule so that during the two-week period all people who enrolled in the study were assigned to either the intervention or the control group (depending on the two-week period schedule assignment). This resulted in a total of 27 recruitment rounds for the intervention group and 27 recruitment rounds for the control group (i.e., 108 weeks in total).

The assignment schedule was blinded to the researchers during the inclusion period. However, at certain times during the data collection process, the intervention received heavy media coverage, which may have influenced the likelihood of divorcees to join the study during these periods and explain the uneven allocation ratios (i.e., control group 44.5%; intervention group 55.5%). A total of 1,882 participants enrolled in the study and upon completion of the baseline survey, 1,050 were randomized into the intervention, and 832 into the control group. Of the individuals assigned to the intervention group, less than 1 percent (n = 8) elected not to use the intervention during the intervention period.

To assess possible selection bias introduced by allocation into the intervention or control groups, participants in these groups were compared on sociodemographic variables (gender, age at survey, education, income), divorce-related characteristics (marriage duration, times divorced, divorce initiation, having children, conflict degree with a former spouse), and relevant health-related variables (depression, anxiety, stress, and mental and physical health). There were no significant differences observed in the odds ratios of belonging to either of the two groups suggesting that the study randomization was successful (for details, see Table 1).

Attrition rate. Consistent with the high dropout rates of online-health evaluations (Donkin et al., 2011; Eysenbach, 2005; Geraghty et al., 2012; Lie et al., 2017) response rates dropped to 27.9% from T1 (n = 1,050) to T2 (n = 293) in the intervention group and to 29.8% from T1 (n = 832) to T2 (n = 248) in the control group. Attrition substantially decreased afterward, resulting in little change in group size over subsequent follow-ups (intervention group: T3 = 320 and T4 = 295; control group: T3 = 238 and T4 = 211).

Attrition bias. To determine if the attrition rate biased our findings, participants who only participated at baseline were compared to the rest of the sample in both the control and intervention groups. Participants were compared on sociodemographic (group membership, gender, age at survey, education, income), divorce-related (times divorced, marriage duration, number of children, conflict degree with a former spouse), and mental and physical health indicators (depression, anxiety, somatization, stress, mental and physical health). In the intervention group, multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that younger participants (AOR = -0.99, p < .05) and those of poorer physical health (AOR = -0.91, p < .05) were more likely to drop out. No indicators significantly predicted group membership in the control group. Nevertheless, all selected variables were included as controls in the main analyses. Further details are provided in Appendix A and B.

Procedure

These results are part of a larger 12-month longitudinal RCT study entitled Cooperation after Divorce (CAD). The intervention study sought to assess effects of the CAD online intervention on well-studied negatively affected psychological and physical health outcomes associated with divorce (perceived stress, anxiety, depression, somatization, mental and physical health, hostility, and parent reports of children's health-related quality of life). The study began in July 2015 through a collaboration with the Danish State Administration (DSA).

Initially, from July 2015 to January 2016, a trial period was initiated to test the CAD solution, user functionality, and data collection process. Subsequently, the effect study was carried out from January 2016 to January 2018. During this period, people initiated their legal divorce and separation procedures through the submission of an application to the DSA. Divorce was granted immediately in cases of mutual agreement. If there was disagreement to the divorce or its terms, a 6 months separation period was initiated after which the divorce was finalized – even in the absence of mutual agreement at the end of the separation period. According to the DSA, during the study period, approximately 70% of divorces were granted divorce without a separation period. From application submission to divorce decree issuance, the average processing time was 2-3 weeks in cases of mutual agreement to the divorce. With the official juridical divorce decree, the DSA sent a participation invitation letter and information regarding the study. In order to enroll in the study, divorcees used a digital link included in the invitation letter, created an account on the CAD platform, gave informed consent, and completed the baseline survey. After this, the system randomized participants into the intervention or the control group according to the blinded randomization schedule (see the Randomization bias section for a detailed description). The control group received treatment as usual (i.e., no systematic treatment) while the intervention group received free access to the CAD intervention. There was no compensation for study participation for members of the intervention group (except for access to the intervention) whereas control group members were entered into a raffle for cinema tickets.

The 3, 6, and 12-month follow-up surveys were conducted by contacting participants via e-mail at the email addresses provided by them at baseline. All responses were anonymized and stored in anonymous form on a secure server. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The research was exempt from further ethical evaluations following the rules and regulations set forth by the Scientific Ethical Committees of Denmark.

The Cooperation after Divorce Intervention (CAD) Intervention Platform

The CAD digital intervention platform consists of 17 digital learning modules addressing the following dimensions and themes:

Yourself, includes six themes: a) how divorce affects you, b) let go and forgive, c) coping with grief, d) ways to deal with negative thoughts, e) how to handle a crisis, and f) anger management.

The Children, comprising four themes: a) how children experience divorce, b) understanding children's feelings and reactions, c) putting children's needs first, and d) how to communicate with children about divorce.

Co-parenting, consists of seven themes: a) avoiding typical pitfalls, b) making clear agreements, c) how to get through holidays and birthdays, d) roads to good co-parenting communications, e) dealing with conflicts, f) create good co-parental cooperation, and g) find common ground in child-rearing (see Appendix A and B for a more detailed description of the intervention).

Participants in the intervention group accessed the online CAD intervention from a computer, mobile device, or tablet. Modules each required 30-60 minutes to complete. Module content and themes address well-known areas that are relevant to individuals after divorce (Sander & Hald, 2020) to provide a combination of knowledge and tools designed to teach divorcees relevant coping strategies, and adequate behavioral changes and behaviors. Members of the intervention group choose freely which modules to engage with, when to engage them and for how long. This individually tailored approach was employed as divorce is a heterogeneous process (e.g., Symoens et al., 2013; Malgaroli et al., 2017) and the experience and needs of divorcees may change from one individual to the next and/or over time. As the intervention is individually tailored, the ideal dosage cannot be calculated. In the current study participants on averaged used 4.27 modules (SD = 2.94). For more detailed descriptions of the CAD intervention, please see Appendix A and B.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables. Several socio-demographic variables were assessed: a) Sexual identity was assessed by the following question: “Are you a man or a woman?” with the response options: 1 = man 2 = woman; b) Age at divorce was measured in years and months; c) Education level was assessed by the question: “What is the highest education you have completed?” with the following response options: 1 = low level of education (e.g. primary school, high school, business high school, vocational education), 2 = medium level of education (e.g. medium-cycle tertiary education, bachelor's degree) and 3 = high level of education (e.g. master's degree or higher); d) Monthly income was reported on a nine-point scale with 10,000 DKK intervals (approx. 1500 USD; at the time of the intervention, 1 USD approximated 6.50 DKK), from 1 = below 10,000 DKK to 8 = more than 80,000 DKK. According to Statistics Denmark, salaries may be categorized as: 1 = below average (≤ 30,000 DKK), 2 = average (30-40,000 DKK), and 3 = above average (≥ 40,000 DKK).

Divorce-related variables. We also assessed a variety of marriage and divorce-related variables: a) Marriage duration was calculated in years and months from marital date to the official divorce date; b) Divorce duration was calculated in days from the official date of divorce to the baseline survey response date; c) Number of divorces was obtained by asking participants: “How many times have you divorced?” with response options including 1 = one time, 2 = two times, 3 = three times, and 4 = more than three times; d) Parenthood status and Number of children were determined by asking how many children the participants had; e) Children's age was calculated from the birthdate(s) provided by the participants; f) Degree of conflict was assessed by the 6-item self-report Divorce Conflict Scale (DCS). The DCS assesses six dimensions of divorce-related conflict: communication, co-parenting, global assessment of former spouse, negative and pervasive negative exchanges and hostile, insecure emotional environment, and self-perceived conflict (Hald et al., 2019). The internal consistency of the scale was high (Cronbach's α = .88).

Individual differences. We assessed various individual difference variables that were used in the attrition bias analyses. Specifically, a) Mental health and b) Physical health were assessed using the second version of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Assessment (Ware et al., 1993). In the SF-36 mental- and physical health is calculated on the basis of scores on eight health-related subdomains including: physical functioning, role participation with physical health problems (role-physical), bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role participation with emotional health problems (role-emotional), and mental health. In the current study, all of the eight health-related subdomains demonstrated high internal reliability across all four time points (Cronbach's α = .81-.93).

Symptoms of c) Depression, d) Anxiety, c) Somatization, and d) Hostility were assessed using the Danish version (Olsen et al., 2004) of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 2000). The measurement of depression included 13 items while anxiety, somatization and hostility included 10, 12, and 6 items respectively. For each item, responses were given on a 5 point Likert scale with response options 0 = not at all to 4 = very much. Higher scores indicate more symptoms of depression, anxiety, somatization, and hostility. All four scales demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach's α = .78-.95) at all four data collection points.

Perceived stress. The Danish version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Eskildsen et al., 2015) was used to assess the degree to which participants experienced their lives as stressful. The PSS is a 10-item self-report instrument with a five-point Likert-type response scale (0 = never, 4 = very often). Scores range from 0-40 with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress. Total sum scores over 15 for men and 17 for women are considered indicative of high-stress levels (Cohen et al., 1983; Eskildsen et al., 2015; Nielsen et al., 2008). The PSS has been widely used in research and demonstrated good internal reliability at all measurement points in the current study (Cronbach's α = .90-.92).

User data. Intervention usage was determined by summing the number of started and completed modules of each participant over the 12 months study period.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed and reported on an intention to treat (ITT) basis by including all randomized participants in the statistical analysis regardless of the received treatment (Gupta, 2011). To enable robustness of the longitudinal estimates, along with the assessment of attrition bias (please see the Participant section), all available data were used in the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation approach to protect against any informative missing pattern (Little, 2013). In this method, missing values are not replaced or imputed, but the model is estimated with all available information and provided with population parameters that would most likely produce the estimates from the sample data analysed.

A linear mixed-effect regression modeling was employed using the lme4 package for R version 3.5.3. The exposure variables were measurement time points, group allocation and their interaction, which were all treated as categorical variables because actual measurement times differed very little from the planned schedule and thus did not vary between participants. Treatment effects were quantified as mean differences at 3, 6, and 12-months with Cohen's d effect sizes inferred from the model fit (i.e., the mean difference divided by the standard deviation on the considered outcome). Any effect of the intervention was assessed by a likelihood ratio test for no effect of group assignment at any time point while random intercept accounted for individual differences in initial stress levels. In the second step, the effects were controlled for gender, age, education, income, times divorced, number of children, duration of marriage, conflict degree, physical and mental health, depression, anxiety, somatization, and hostility levels in order to account for possible attrition bias.

To further qualify the effects of the intervention, composite stress scores at the 12-month follow-up for the intervention and control groups were compared with normed perceived stress means from a Danish national representative study by Nielsen et al. (2008) using t-tests. The study by Nielsen et al. (2008) is a Danish population study on characteristics of individuals with high levels of perceived stress in Denmark. The study comprises 10,022 participants (4,676 men and 5,346 women) from the fourth National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) conducted in 2005 in Denmark. The stress measure used in the Nielsen et al.'s (2008) study study corresponds to the measure used in the present study thereby facilitating a direct comparison of stress.

Results

The baseline (T1), average score on the self-perceived stress measure was 18.73 for men (SD = 7.18, median = 19.00, mode = 21.00, range = 0-40) and 19.87 for women (SD = 6.98, median = 20.00, mode = 21.00, range = 0-40). In total, 65% of men (sum score ≥ 15) and 58% of women (sum score ≥ 17) scored equal to or higher than the recommended cut-off value for high levels of perceived stress as suggested by Nielsen et al. (2008). There were no significant differences in self-perceived stress levels in the intervention and the control groups at baseline (b = 0.01, SE = 0.04, t = 0.25).

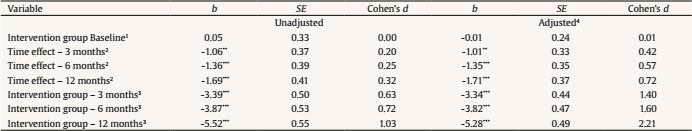

Pertaining to the study hypothesis, linear mixed effect modeling was employed to assess the treatment effect of the CAD intervention on self-perceived levels of stress. Overall and at each time point (i.e., at 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline), the CAD intervention effect was found to be highly significant (p < .0001 (see Table 2 and Figure 2). Even after controlling for potential selective drop-out, at each time point the intervention group scored significantly lower on self-perceived stress than the control group (p < .0001) with the magnitude of these differences being large in size (Cohen's d = 1.40-2.21). Within-group analyses also revealed a significant (p < .0001) decline in self-perceived stress levels after 12 months indicating a time heals effect (see also the Introduction and Table 2).

Table 2. Results for the Study Outcome of Stress using Linear Mixed Effect Modeling

Noteb = standardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error; Cohen's d = standardized measure of effect size; time effect = the control group; 1intervention group compared to the control group at baseline; 2within group comparisons, i.e., the control group compared to baseline at each time point (3, 6, 12 months); 3between group comparisons, i.e., the intervention group and the control group compared at each time point (3, 6, 12 months); 4adjusted (controlled) for the (measured) imbalances in drop-out (e.g., gender, age, education, income, times divorced, number of children, duration of marriage, conflict degree, physical and mental health, depression, anxiety, somatization and hostility levels).

*p < .05

**p < .01

***p < .001.

Note. Time point 1 = baseline; time point 2 = 3-month follow-up; time point 3 = 6-month follow-up; time point 4 = 12-month follow-up.

Figure 2. Self-perceived Stress Mean Score at each Time Point of Collection.

A 3-way interaction between gender, group assignment, and treatment was included in the analyses to further assess the intervention effect. It was found to be non-significant (p < .05), indicating that the treatment effect of the CAD solution on self-perceived stress did not differ between men and women.

Pertaining to the study research question, Figure 3 provides contextualization of the intervention effect by comparing the average levels of perceived stress reported by the intervention group and the control group at the 12-month follow-up to Danish population based normed perceived stress data (Nielsen et al., 2008) using one-sample t-tests.

The perceived stress levels reported by participants in the intervention group did not significantly differ from the normed stress data of separated/divorced Danes from the background population at 12-month follow-up: men, t(85) = -1.01, p = .32; woman: t(140) = -0.61, p = .54 . However, compared to the general background population, women, but not men, in the intervention group scored higher on self-perceived stress at 12-month follow-up with the magnitude of this difference being small-medium in size: men, t(85) = .54, p = .59; women, t(140) = 2.32, p = .02, Cohen's d = 0.39; see also Figure 3.

In the control group, both men and women reported significantly higher stress levels than both the general Danish population, men, t(50) = 6.86, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.94; women, t(137) = 9.77, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.67, and separated/divorced Danes, men, t(50) = 5.91, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.67; women, t(137) = 7.43, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.27, with the magnitude of these differences being large in size (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparisons at the 12-Month Follow-up of Self-perceived Stress Mean Scores of the Intervention and Control Groups with Danish National Normed Population Data.

Further, we found that 61% of men (sum score ≥ 15) and 56% of women (sum score ≥ 17) in the control group scored equal to or higher than the recommended cut-off value indicative of high levels of self-perceived stress (Nielsen et al., 2008) while the corresponding numbers in the intervention group was 24% for men and 31% for women.

Discussion

Across gender and pertaining to the study hypothesis, we found that the digital intervention CAD significantly reduced self-perceived stress with the magnitude of the improvement effect being large in size and evident at both 6 and 12 months follow-ups. Moreover, pertaining to the study research question, we found that at 12-month follow-up, self-perceived stress levels for both men and women in the intervention group were not significantly different to the general background population of separated/divorced individuals whereas for the control group, stress levels were significantly elevated as compared to the general background population of separated/divorced individuals.

An important issue in the divorce literature is the question of whether divorce constitutes a crisis or chronic strain and what the post-divorce trajectories of stress are (Amato, 2000). The results of this RCT study suggest that perceived stress levels slowly decrease over the first 12 months post-divorce without intervention, similar to the findings reported elsewhere (e.g., Booth & Amato, 1991), suggesting a stress-reducing effect of time (i.e., a 'time heals effect'; Thuen, 2001). However, in this study at the 12-month follow-up, participants in the control group still reported significantly higher stress levels than normed population data, with 61% of men and 56% of women reporting stress levels equivalent to high levels of self-perceived stress (Nielsen et al., 2008). In contrast, our analysis demonstrated that the intervention group was characterized by a significant decline in perceived stress levels at all follow-up time points (3, 6, and 12 months) when compared to the control group. Further, that the intervention group's reported perceived stress levels at 12 months follow up did not differ from divorced/separated individuals in the background population and that only for women stress levels were slightly and significantly higher than those of the general population although approximately a quarter of both men and women still experienced stress levels indicative of high self-perceived stress. Overall, we find that these results suggest that in a stress perspective, divorce may both be understood as a crisis from which most divorcees recuperate with the right support and as chronic strain. This interpretation corroborates divorce studies suggesting that in the longer-term (i.e., 3+ years), most divorcees adapt quite well to divorce while approximately 20% of divorcees experience pronounced psychological problems and lower well-being even years after their divorce (see also Perrig-Chiello et al., 2015). In this connection, the study results also highlight the potential utility of online interventions to reduce stress or accelerate stress reduction among newly divorced individuals. As previous research has established the long-term detrimental effects of high/prolonged stress, the intervention-related reduction in stress, as observed in the current study, has the potential to substantially impact future well-being among divorced individuals and improve public health.

Consistent with other studies that find higher stress among women (Beam et al., 2017; Lee & Dik, 2017; Nielsen et al., 2008), gender was associated with higher baseline (i.e., within a week after legal divorce) stress levels, with women reporting higher stress levels than men. However, when assessing gender interaction in the linear mixed effect models, gender was not significantly associated with stress at any of the follow-ups nor with trajectories of change in stress over time. This suggests that while women report higher initial stress levels, their rate of stress reduction is not significantly different from those of their male counterparts.

The finding that the CAD intervention was effective in reducing perceived stress among recently divorced Danes could be due to several of its characteristics. First, members of the intervention group could access the intervention content on demand. That is, when and where it was convenient for them, which could have increased the usage (Dennis & Ebata, 2005). Moreover, participants could select to complete any of the 17 modules when they wished and therefore access information that was relevant to them at their moment of need. As divorce is not a homogeneous process and the needs of divorcing adults could be heterogeneous (e.g., Hilpert et al., 2018; Karney & Bradbury, 1995), allowing individuals to access content that they find relevant at a specific point in time may substantially contribute to stress reduction (e.g., Atkinson & Gold, 2002). Further, the content of the intervention targets well-known and studied challenges that adults undergoing divorce face, including communication with their former spouse, co-parenting strategies, understanding their own and their children's emotions and reactions to divorce. Moreover, the intervention provides clear guidance for attitudinal and behavioral change. Altogether, this may promote the thematic and practical utility of the intervention as well as increased self-efficacy, emotional support, and better coping abilities. As coping methods are integral to the stress response, fostering such abilities are vital for the reduction of stress (Allen et al., 2014; Budtz-Lilly et al., 2015; Cohen et al., 1997; Cohen et al., 1983).

When evaluating the study results, the following limitations should be considered. By being an RCT intervention study, there may be a selection effect by which those with higher stress levels could be overrepresented, seeking help to relieve their stress. Similarly, those with higher stress levels could also be underrepresented, finding it additionally stressful having to participate in an intervention study over 12 months at a likely stressful time of their life. Additionally, we were unable to determine if both partners in a prior marriage participated in the study, which may affect the independence of data in the study. Moreover, on average, the current study sample was found to be better educated than the general Danish population of divorcees, which may limit the generalization of results. Considering the high attrition rate observed in this study (though comparable to other studies; see also Cugelman et al., 2011; Eysenbach, 2005), which is always potentially problematic as a source of participation biases, we found little differences between those who completed all follow-ups and those who only completed the baseline questionnaire. To further minimize attrition bias, in the multivariate analyses we controlled for a range of socio-demographic, divorce-related, mental health and physical health indicators. Finally, this study did not investigate all plausible mediators and moderators of the intervention effects, for example, individual differences such as personality or divorce-related characteristics. As intervention effects in the area of divorce research may be related to individual differences and/or divorce characteristics (Amato, 2000; Dalton et al., 2003; Kołodziej-Zaleska & Przybyła-Basista, 2016; Malgaroli et al., 2017; Symoens et al., 2013), future studies should include mediation analysis and test plausible moderators to examine the intervention effects of CAD on perceived stress symptoms.

Conclusion

Using an RCT study design and mixed linear effects modeling, the study found that the CAD intervention was highly effective in reducing stress levels among recently divorced Danes. Further, that these intervention effects were maintained 12 months post juridical divorce. Finally, that the intervention effect brought stress levels in the intervention group down to national norms. The results may have important implications for the potential services offered to newly divorced individuals by demonstrating the utility of the CAD online intervention on stress among individuals transitioning from being married to divorced.