INTRODUCTION

The first thoracic window or thoracostomy was carried out by Elloesser in 1935, to treat a tuberculous empyema in a lung that had not been resected. Claggett and Geraci described a method of open drainage in the post-pneumonectomy empyema, to prevent deforming thoracoplasty. They resected a rib and left the wound open for daily irrigation with a solution of neomycin at 0.25% until the cavity was sterilised, proposing to subsequently close the thoracostomy. Years later it was abandoned as a treatment, and was taken up again after the Second World War. Vikkula and Konstiainen described a similar method, but by creating a larger window, resecting two or three costal arches. The window was systematically used on bronchopleural fístulae. In 1986, Weissberg considered this technique to be useful for patients with chronic empyema, without necessarily being pneumonectomysed, with or without bronchopleural fístula, leaving the window to close spontaneously1.

Wounds commonly occur with tuberculosis, such as recurrent pleurisy, the rupture of a necrotic wound in the pleural cavity or complication of an adjacent artificial pneumothorax, which are often the cause of chronic empyema2. A cured pulmonary tuberculosis, in the phase of residual fibrosis, which leads to retractions in the parenchyma with emphysema and bullae in the region of the pleura, is a relatively frequent cause of secondary pneumothorax3. However, it is a very rare complication during active pulmonary infection4,5.

The thoracic window is a low-incidence surgical technique, recommended as one of the last resort therapeutic resources for resolving a pleural or thoracic empyema with cleaning and drainage of the pleural cavity. Managing patients in this situation requires specific nursing care and skills6. This type of management and care is uncommon in prisons. It is a low-incidence alternative treatment, and is even more so in the primary healthcare unit of a prison.

Nursing professionals in prisons should carry out comprehensive nursing care on all patients that require a wound to be healed, not just those with chronic processes. Their work cannot be limited to treating the wound, but rather a complete evaluation should be completed with a holistic approach that helps to ensure that interventions being conducted are suitable for the patient, applying the nursing process or methodology, or as Alfaro-LeFevre reminds us: “providing humanistic care focused on efficiently achieving objectives (expected outcomes)”7.

The use of the nursing methodology in the prison environment continues to be ignored by most professionals working in this area. According to a study carried out on Primary Healthcare in the Canary Islands8, the use of the nursing methodology is related to more computerisation, a larger number of nursing appointments and with the development of more specific training. The most widely used taxonomy in nursing methodology is NANDA, NIC, NOC (N-N-N). They are recognised nursing languages and, according to Royal Decree 1093/2010, which approves the minimum set of data in the clinical reports of the National Health System9, they define the ones that should accompany the nursing care reports, such as the nursing diagnoses, objectives and interventions, according to the NANDA, NIC, NOC nomenclature.

This study presents a clinical case of an inmate at the Murcia I Prison, using Marjory Gordon’s functional patterns10 and the NANDA-NIC-NOC taxonomy11, in order to carry out a complete evaluation of the patient and care of the wound, and to try to ensure that the healing process takes place as soon as possible and with minimum complications. Comprehensive care of the patient is considered to be important for obtaining better health outcomes, thereby improving the highly impaired quality of life of patients who are serving sentences in prison.

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

The clinical case of an inmate is described, which included highly complex features both for the nursing staff and the medical unit, who presents a thoracic window or thoracostomy window carried out in April 2016. It is a descriptive study of the progress of the wound from when he entered Murcia I Prison (from 11 October 2016 to January 2018), using nursing methodology with the NANDA, NIC, NOC (N-N-N) language.

The corresponding authorisation and the patient’s informed consent were requested from the General Directorate of Prison Healthcare to carry out the research work.

The case consisted of a 43 year old male, carrier of a thoracostomy window in the thoracic wall after pneumothorax and complex symptoms of tuberculosis, with empyema and persistent leakage. He was treated in Alicante Hospital, while he was interned in Villena Prison, where the thoracic window was opened to clean and drain the pleural cavity, and to assist in the process of filling and healing it. After entry in Murcia I Prison, the patient’s symptoms were monitored in the Thoracic Surgery Service of the Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital (HUVA) and in the Internal Medicine Service of Murcia. Surgical closure of the cavity was considered to be impossible due to the major risk of severe infection.

History Prior to Entry in Murcia I Prison

The patient does not have high blood pressure, diabetes or any known dyslipidemia. He smokes 10 cigarettes/day. He does not consume alcohol, but there is a background of intravenous drug use. The patient’s education was basic and he has been in prison for over 23 years. The patient reports that he consumed cocaine because “it calmed him down”. He was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in 1990, although he did not voluntarily commence antiretroviral therapy (ART) until 2005, after termination of treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis at the Valencia General Hospital. He also presents pulmonary tuberculosis with several episodes: one in 2004 (treated) and another in January 2016. In January 2016, he asked for voluntary discharge from the General University Hospital General of Elda, after suffering from a pneumothorax that required thoracic drainage. He subsequently presented a complicated pneumothorax that required a pleural drainage tube. The bronchial aspirate taken from a bronchoscopy showed a positive direct smear for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, therefore anti-tuberculosis treatment was initiated. The air leakage and lung collapse continued for over two months, so the decision was made to carry out surgical treatment with parieto-visceral pleural decortication. After surgery, evolution was slow, with no resolution of the lung collapse or the air leak, and so on 19 April 2016 a thoracostomy window was carried out, 20 x 10 cm left of Eloesser, so as not to depend on the drainage and carry out local healing of the pleural cavity, and the patient was discharged eight days later. In October 2016, he was admitted to the Thoracic Surgery Service of the HUVA to monitor progress and heal the thoracic window. In April 2017, two ulcers were observed in the hiliar area, the cultures of which showed Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Current treatment: 1 tablet/day (combo) of efavirenz+emtricitabine+tenofovir and 2 tablets/day (combo) of rifampicin+isoniazid, with daily dressings at the Murcia I Prison and every month at the thoracic surgery outpatients unit of the HUVA.

Evaluation of Marjory Gordon’s Patient Functional Health Patterns

The APRIDE (nursing diagnoses prioritisation algorithm (algoritmo de priorización de diagnósticos enfermeros))12 tool was used. This system is designed to make the nursing evaluation process easier by using a standard assessment model and a subsequent prioritisation of the diagnoses found (Table 1).

Table 1 Prioritisation stage of the diagnoses obtained.

| Main diagnostic tag | Impacts | Type diagnosis | Domain/clase | Total points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00099 - Ineffective health maintenance | 8 | Real | D01C2 | 226 |

| 00146 - Anxiety | 10 | Real | D09C2 | 188 |

| 00046 - Impaired skin integrity | 3 | Real | D11C2 | 100 |

| 00114 - Relocation stress syndrome | 9 | Real | D09C1 | 170 |

Pattern 2 was prioritised (nutritional-metabolic pattern) along with the NANDA (00046) diagnosis: impaired skin integrity related to mechanical factors, shown by a tissue wound, for being a patient that needs daily nursing care with a highly complex wound that requires maximum vigilance.

According to the functional pattern nursing evaluation, the nursing diagnoses, indicators, interventions and main activities were prioritised, as per the online tool NNNConsult13, which enabled the standardised languages developed by NANDA International, the results of the NOC, the interventions of the NIC and links between them to be quickly consulted (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Table 2 Nursing diagnoses, objectives or results and activities.

| NANDA diagnoses | Expected outcomes NOC | Main indicators | Interventions NIC | Main activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Pattern:nutritional-metabolic. (00046) Impaired skin integrity related to mechanical factors, shown by tissue wound. | (1103) Wound healing: secondary intention. Initial score: 1. Daily score: 5. Expected time: during stay in prison. | (110321) Decreased wound size. Scale value: 3, moderate. (110301) Granulation. Scale value: 3, moderate. | (3660) Care of thoracic window. (3590) Inspection of skin. | (366007) Monitor characteristics of wound. (366006) Observe ulcers, bleeding, sloughing, secretions, colour, size, smell. (366014) Describe interventions carried out. Daily treatment of wound as per protocol. |

| 7-Pattern: self perception-self concept. (000146) Anxiety related to threat of loss of health, shown by confusion, concerns expressed due to changes in vital events and insomnia. | (1211) Anxiety level. Initial score: 3. Daily score: 5. Expected time: during stay in prison. (1302) Coping. Initial score: 3. Daily score: 5. Expected time: during stay in prison. | (121117) Verbalised anxiety. Scale value: 3, moderate. (130203) Verbalises sensation of control. Scale value: 3, sometimes shown. | (4920) Active listening. (5230) Coping enhancement. (5820) Anxiety reduction. | (492011) Encourage expression of feelings. (523017) Help patient to identify the information that he is most interested in obtaining. (582005) Encourage patient to express feelings, perceptions and fears. (582012) Listen attentively. |

| 1-Pattern: Health awareness-health management. (00099 ) Ineffective health maintenance related to ineffective individual coping, shown by lack of adaptive behaviours to internal or external changes. | (0313) Self-care status. Initial score: 1. Daily score: 4. Expected time: during stay (1602) Health promoting behaviour. Initial score: 1. Daily score: 4. Expected time: during stay (1813) Knowledge: treatment regimen. Initial score: 1. Daily score: 4. Expected time: during stay in prison | (031308) Controls oral and topical medication to meet therapeutic objectives. Scale value: 4, slightly compromised. (160205) Uses effective behaviours ro reduce stress. Scale value: 4, frequently shown. (181310) Description of nursing process. Scale value: 4, substantial. | (2380) Medication management. (4470) Reinforcement of self-directed change. (5230) Coping enhancement. (5602) Teaching: disease process. | (238009) Determine what drugs are needed and administer as per medical prescription and/or the protocol. (447007) Encourage the patient to examine personal values and beliefs and satisfaction with same. (523002) Encourage patient find a realistic description of the change of role. (523006) Encourage a realistically hopeful attitude as a way to manage feelings of impotence. (560203) Comment on changes in lifestyle that may be necessary to prevent future complications and/or control the disease process. |

Note. NANDA: North American Nursing Diagnosis Association. NIC: Nursing Interventions Classification.

NOC: Nursing Outcomes Classification.

Development

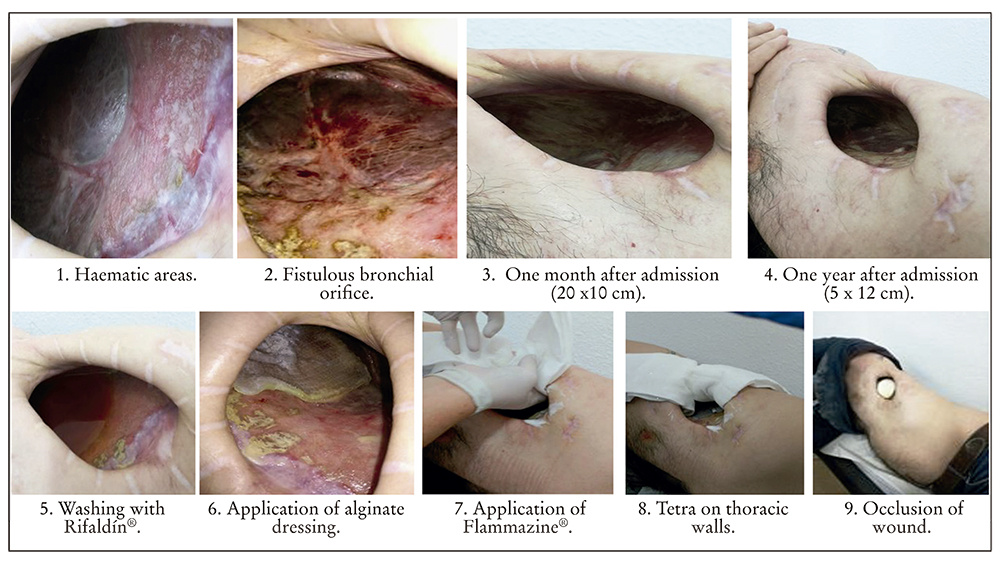

When the inmate was admitted (11 October 2016), he presented a left thoracic cavity or window of 20 x 10 cm, with sloughs and granulation tissue in good condition, but without the possibility of surgical closure of the cavity due to the major risk of severe infection in view of the comorbidity and history. Prior to entering prison, the dressings were carried out at the Jumilla Health Centre (Murcia). He was admitted to the Surgery Service of the HUVA, from where he returned in December 2016. Figure 2 shows graphic images of the progress, of the way the dressings are applied, and of the size of the wound when he was admitted and one year after.

The care protocol when the patient was admitted consisted of applying seven swabs with an antiseptic: internally applied 10% povidone iodine. In the hospital, treatment was applied by washing with hydrogel in solution (Protosan®) and in October 2016 the treatment was changed to a wash with physiological saline solution and a sponge with soapy chlorhexidine to clean the cavity of the slough and exudate from the application of silver sulphadiazine cream (Flammazine cerio®). The lung was not rubbed but dried and hydrofibre dressings with ionic silver (Aquacel Plata®) dampened with saline solution or transparent hydrogel (Nugel®) were applied to the lung, to prevent continuous exposure of the silver sulphadiazine to the lung. It was dried and three swabs filled with half a swab impregnated with silver sulphadiazine were applied. The side of the compress with silver sulphadiazine was placed in contact with the thoracic wall and the diaphragm (one in the anterior and diaphragmatic region, another in the superior and anterior area, and another posterior). Two or three rolled compresses were applied separately on the hole in the wall, and the ends of the three swabs were folded on top.

On 5 April 2017, the inmate presented self-limited bleeding. Treatment was applied for three alternate days, with a wash with physiological saline solution and chlorhexidine, and a dressing of Linitul® with sterile vaseline was applied, open over the entire inner and exterior surface of the wound, without requiring Aquacel® or Flammazine®, so as to prevent continuous rubbing on the granulation tissue. Swabs were then applied to the wound. The bleeding improved with Flammazine®.

On 26 May 2017, the inmate presented an ulcerative wound, non-exudative, that made an impact because it was on the pulmonary bed, next to the bronchial plane (did not present air leak). Smears were for micro-bacteria. The treatments were maintained on alternate days (Linitul®/Flammazine®). He presented an orifice in the anterior hiliar area, with an appearance leading to suspicions of a bronchial fistula from tuberculosis. A positive result for several bacteria was obtained and the PCR was positive for M. tuberculosis, and so the patient was once again admitted to hospital. A new smaller fistulous orifice at about 2 cm from the anterior was seen, likewise in the hiliar area. No leaks were present after checking with saline solution (orifice with a caseous appearance). He followed treatment with respiratory isolation. The wound treatment was changed to washing with a chlorhexidine and saline solution sponge and washing with rifampicin (a vial diluted in 250 ml of physiological saline solution). It was left for 5 minutes and removed with compresses. The Aquacel Plata® dressing was applied to pulmonary bed, three half compresses with cerio®, covering the inner surface of the thoracic wall, and vaseline on the edges of the skin around the thoracostomy.

In June 2017, the inmate returned to the Murcia I Prison and in September the fistulous orifices closed with a minimum of fibroid exudate. Treatment was modified with the application of an alginate dressing without silver on the pulmonary bed. The wound had a good appearance. In October treatment was carried out with Flammazine® on alternate days, coinciding with the alginate treatment. On the days without Flammazine®, treatment was applied with Aquacel®. In November, the inmate presented a local infection from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In December, the inmate’s wound progressed favourably, and presented an epithelisation of the edges of the thoracostomy with the alternative treatment method currently being applied. The size of the wound is 5 x 12 cm. The fistulous orifices have closed, the patient is stable in treatment, with constant monitoring by nursing staff.

Efforts were made to clarify and clear up any queries that the patient had, and he was informed of the changes observed, and of the type of treatment applied, thereby obtaining a good atmosphere of trust.

DISCUSSION

The indicators in the altered patterns were: nutritional-metabolic (reduction of wound and granulation). Within a Likert scale, with ranks from 1 to 5, they passed from 1 to 3 (from “none” to “moderate”). The self-perception/self-concept (verbalised anxiety and sensation of control) changed from 1 to 3 (from “none to moderate” and from “never shown” to “sometimes shown”). Health awareness/health management (controls oral and topical medication to meet therapeutic objectives, uses effective behaviours to reduce stress, and description of the process of the disease) changed from 1 to 4 (from severely compromised to slightly compromised, from never demonstrated to almost always demonstrated and from none to substantial). All the changes were determined at the end of one year.

The NOC results were: wound healing (from 1 to 3), level of anxiety (from 3 to 4), coping with problems (from 3 to 4), self-care level (from 2 to 4), health promotion (from 2 to 4), therapeutic regimen (from 2 to 4). All the changes were determined after one year of monitoring.

The inmate presented multi-pathology and was a highly complex patient that required constant monitoring and daily evaluation by nursing professionals, to establish if referral to more specialised healthcare resources was necessary6,14. Nurses should refer patients attended in their field of competence to other services15 and establish more direct communication to bring about more involvement on their part when preparing nursing reports, in which they comment on their evaluations, monitoring and interventions, using their own nursing language.

Daily care of a wound is a process carried out by nursing staff as a practice in their daily activities. The aim with this specific case is to demonstrate that is not just an isolated activity; the patient should receive comprehensive management, not only focusing on the reason for the consultation, but also assessing the different functional patterns in order to establish which have changed so as to take the evolution of the process into account, and provide better care and improved quality of life for the patient16. If the inmate’s care is comprehensively addressed, a climate of trust can be created, enabling the patient to adapt to difficulties and reduce anxiety, which are very necessary factors for curing a wound.

After daily contact, the patient’s wound progressed satisfactorily, the patient showed better adaptation to the clinical situation and his confidence in a possible positive outcome increased. The nursing methodology applied to the patient enabled the following observations to be made: he accepted the changes to his body image, his fear about coping with the situation diminished and, to sum up, management of his own health improved.