Introduction

1.4 million people die every year worldwide from viral hepatitis, and 47% of these deaths are caused by hepatitis B1, which affects 296 million people2. The hepatitis B virus accounts for 20% of all cases in Spain3, although recent years have seen a reduction in the number of notifications4 and in the number of deaths from CHB5. A cornerstone in this reduced incidence has been the use of vaccination programmes6.

Anti-HBV vaccination in Catalonia began in 1984 with a vaccine developed from human plasma, which made it expensive and of limited availability. It was applied to groups at higher risk of infection and recently born children of infected mothers. With the use of a vaccine obtained from genetic recombination in 1990, coverage was extended to pre-adolescents, and vaccination of newborn infants commenced in 20027.

Besides vaccination, other preventive strategies have contributed towards reducing incidence, such as: a) systematic control of blood donations; b) serological screening of expectant mothers; and c) changes relating to high-risk behaviours, such as changing the consumption patterns of drug users, the use of condoms in sexual relations, etc. All this has meant that in the last decade Spain has changed from being a country with an intermediate level of endemicity8 to being regarded as one where endemicity is low, with a rate of acute HVB infection of 0.84 per 100,0004.

According to recent studies, the Spanish Liver Research Association (AEEH) estimates that the prevalence of CHB amongst the Spanish population stands at 0.5% to 0.8%, although this prevalence may have been negatively affected in recent years by the arrival of an immigrant population from countries with high levels of endemicity9, since almost half of the persons currently infected with HBV in Catalonia are immigrants10.

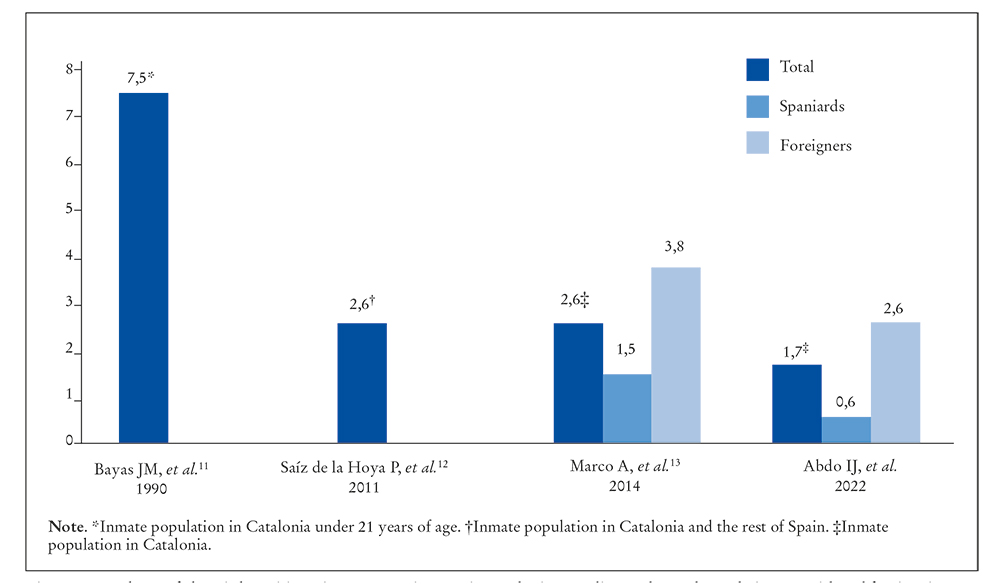

As regards the prevalence of CHB amongst inmates, three major studies have been carried out to date11-13. Their findings coincide in that inmates present a higher prevalence of CHB than in the Spanish community. The first study, published in 1990 and carried out with inmates under 21 years of age showed a prevalence of 7.5%11.

The following studies, completed in 201112 and 201413, showed a much lower prevalence of 2.6%. The latter study highlighted the differences between Spanish and foreign inmates (1.5% of CHB compared to 3.8%, respectively). Since then, and as far as we know, no further research has been carried out, and so the current rate of CHB amongst inmates and the differences, if any, between the prison population and the community, and the Spanish and foreign prison populations are unknown. The objective of this study is to determine the prevalence of CHB amongst inmates in Catalonia, both globally and according to categories, identifying possible predictive variables that may help in the early detection of infection.

Material and Method

The inmates of nine prisons in Catalonia were studied: five of the prisons were in Barcelona (Brians-1, Brians-2, Dones, Joves, Lledoners and Quatre Camins), one in Tarragona (Mas d´Enric), one in Lleida (Ponent) and one in Girona (Puig de les Basses).

The cut-off date for collecting the variables was 13 January 2022. No sampling was carried out and all the inmates housed in Catalan prisons at the time of the cross-section were included.

CHB (persistent hepatitis B+ surface antigen: >6 months) was used as a dependent variable, and the independent variables included: gender, age, place of birth, IDU, coinfections (HIV, hepatitis C virus [HCV] and hepatitis D virus [HDV]), record of syphilis and anti-HBV vaccination.

The “origin” variable was stratified into geographical zones: a) Spain, b) European Union, c) Eastern Europe, d) Latin America and the Caribbean, e) countries in North Africa, f) Asia, and g) Sub-Saharan Africa.

The information source used was the Catalan Primary Healthcare Services Information System (SISAP), which includes the data in the computerised primary care clinical records and information in the clinical record shared with other levels and medical centres. The coverage of the shared clinical record in Catalonia is 85%.

The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) computer program, version 25, was used. The continuous variables were expressed through the mean and standard deviation, or through the mean and interquartile range in cases where the distribution was not parametrical. The categorical variables were expressed in percentages. To measure the association between variables, the chi-squared and Fisher’s exact test were used, where appropriate, along with the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of prevalence with a CI of 95% to measure the association between variables.

Finally, a multivariate logistical regression analysis was carried out to evaluate the association with potential predictive variables that had shown a value of p <0.10 in the bivariate analysis. A value of p<0.05 was regarded as significant in the multivariate logistical regression.

To comply with the requirements regarding the ethics and confidentiality of the data used in the study, the authors complied with the international ethical recommendations (Helsinki Declaration and Oviedo Convention) and the recommendations on best clinical practices of the Spanish government in the Law on Quality and Cohesion of the National Health System (2003). Confidentiality was also guaranteed pursuant to Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights.

The study was anonymised and based on the statistical data of the SISAP, and therefore informed consent was not requested. The project was evaluated and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Jordi Gol University Institute of Primary Care Research (IDIAPJGol), under code number 21/279-P, on 15 December 2021.

Results

6,508 patients (94.7% men) with an average age of 38.5 ± 11.6 years were studied. 55.4% of the subjects had been born outside Spain, 3.5% were infected with HIV and 1.6% reported having been diagnosed with syphilis. 35.9% stated that they had never consumed illegal drugs, 8.8% reported a background of IDU and 55.3% stated that they had consumed illegal drugs but denied that they used drugs intravenously. Other descriptive characteristics, distributed according to whether patients were infected or not with HBV, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the population studied according to potential predictive variables of infection from HBV amongst inmates in Catalan prisons

| Variable | Population without CHB (n = 6399) | Population with CHB (n = 109) | p value of bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value p | AOR (CI 95%) | ||||

| Sex | 0.13 | ||||

| Male | 94.5% | 98.2% | |||

| Female | 5.5% | 1.8% | |||

| Average age | 38.3 ± 11.4 | 39.2 ± 9 | 0.30 | ||

| Age groups (years) | 0.05 | 0.97 | |||

| <21 | 5.4% | 0 | |||

| 22-39 | 50.5% | 57.8% | |||

| 40-59 | 39.3% | 39.4% | |||

| >60 | 4.8% | 2.8% | |||

| Origin | 0.000 | <0.000 | 4.2 (2.5-6.9) | ||

| Non-immigrant | 45.2% | 16.5% | |||

| Immigrant | 54.8% | 83.5% | |||

| Europa | 47.6% | 18.3% | 0.89 | ||

| Latin America and Caribbean | 17.2% | 5.5% | 0.66 | ||

| North Africa | 20% | 18.3% | <0.00 | 2.8 (1.4-5.5) | |

| Asia | 3.6% | 6.4% | <0.00 | 4.2 (1.7-10.4) | |

| Former Eastern Europe | 7.9% | 20.2% | <0.000 | 4.9 (2.5-9.5) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 3.8% | 31.2% | <0.000 | 16.2 (8.6-30.3) | |

| Drug use | 0.06 | ||||

| Does not consume | 35.7% | 47.6% | 0.21 | ||

| IDU | 2.5% | 1.9% | 0.39 | ||

| Ex-IDU | 6.3% | 7.6% | 0.94 | ||

| NIDU | 55.5% | 42.9% | 0.05 | ||

| Record of syphilis | 1.6% | 1.8% | 0.70 | 0.51 | |

| HCV | 11.9% | 11.1% | 1 | 0.97 | |

| HIV | 3.4% | 7.9% | 0.029 | 0.02 | 3.2 (1.2-8.4) |

| HCV-JHIV coinfection | 2.5% | 4% | |||

| Anti-HBV vaccine | 50.3% | 8.2% | <0.000 | <0.000 | 0.1 (0.1-0.3) |

Note. CHB: chronic hepatitis B; CI: confidence interval; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; IDU: intravenous drug use; NIDU: non-intravenous drug use.

109 (1.7%) inmates with CHB were detected. 6.1% presented coinfection with HDV, 11.1% were coinfected with HCV (HCV ribonucleic acid detectable) and 7.9% were coinfected with HIV.

98.2% (n = 107) of the cases with CHB were men (average age of 39.2 ± 9 years) and 1.8% (n = 2) were women (average age of 41 ± 8 years). Only 3 cases (2.8%) were over 60 years of age and no cases were found amongst inmates under 21 years. 37.5% of those coinfected with HBV-HIV had a background of IDU and were older than non-IDU coinfected patients (45 ± 6 years of age compared to 38 ± 3 years; p = 0.01). Clinical data showed that 7.3% presented liver cirrhosis and 0.9%, hepatocarcinoma. 11% were receiving treatment with anti-HBV antivirals, and this was significantly more common amongst patients coinfected with HIV (100% compared to 4.3%; p <0.001).

The rate of CHB varied between 0% and 2.7% depending on the prison (Figure 1). The prevalence was higher than the mean in three prisons: Puig de les Basses (2.7%), Brians-1 (2.3%) and Mas d’Enric (2.1%), while the others presented a lower prevalence, which in the case of Joves stood at 0% (p = 0.03).

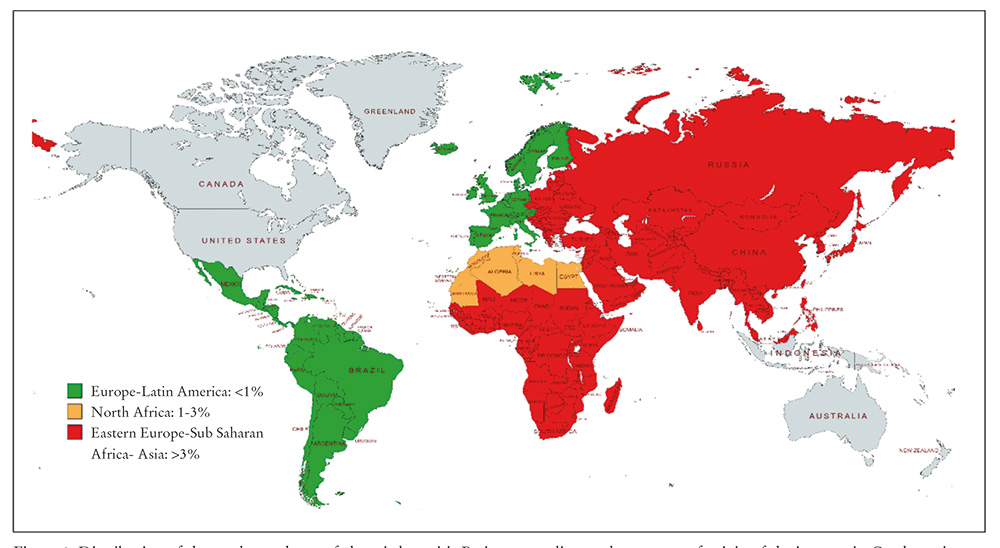

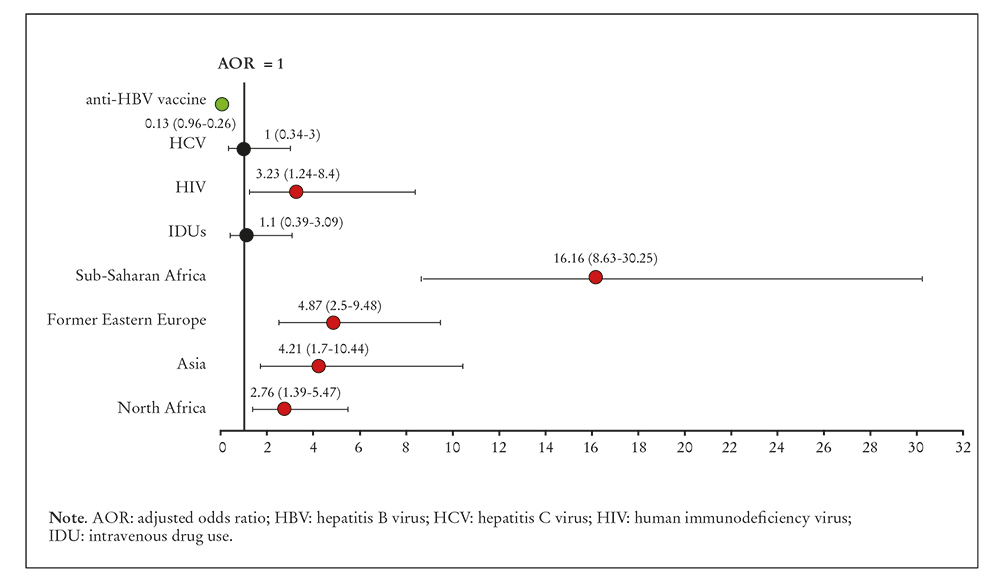

The rate of CHB also varied according to the inmates’ place of origin: 0.6% amongst Spanish nationals, 0.6% amongst the Latin American and Caribbean population, 0.7% for subjects from the European Union, 1.6% for North African patients, 3% for subjects from Asia, 4.4% for patients from former Eastern Europe and 14.1% for persons from Sub-Saharan Africa. Figure 2 shows the distribution of CHB prevalence according to the geographical zones. No statistically significant differences were seen between inmates born in Spain, the EU, and Latin America and the Caribbean (rates of CHB at 0.6%, 0.7% and 0.6%, respectively). However, for patients from North Africa, Asia and former Eastern Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of CHB was 2.8, 4.2, 4.9 and 16.2 times higher, respectively, than amongst subjects born in Spain (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Distribution of the total prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus according to the country of origin of the inmates in Catalan prisons.

Figure 3. Predictive variables of presenting chronic hepatitis B virus amongst inmates in Catalonia according to the adjusted odds ratio.

In overall terms, a higher prevalence of CHB was observed amongst: a) the foreign population (2.6% compared to 0.6% amongst Spanish inmates; p <0.001); b) subjects coinfected with HIV (3.9% compared to 1.8% in non-coinfected patients; p = 0.03); and c) unvaccinated patients (3.1% compared to 0.3%; p <0.001).

The multivariate analysis confirmed the predictive character of: a) being a foreigner (AOR: 4.18; CI: 2.50-6.90; p <0.001); b) coinfected with HIV (AOR: 3.23; CI: 1.24-8.40; p = 0.02); and c) unvaccinated with anti-HBV (AOR: 0.13; CI: 0.06-0.26; p <0.001).

Discussion

This study shows that the current prevalence of CHB amongst inmates in Catalonia is 1.7%, about 2.5 times higher than in the community, where it stands at 0.5-0.8%. However, unlike the findings in previous studies on inmates11-13, the prevalence for Spanish inmates, those born in Latin America and the Caribbean or in the EU is equal to the one found in the community. However, the prevalence is much higher amongst inmates born in North Africa, Asian countries, former Eastern Europe and, above all, in Sub-Saharan Africa, as was observed in other reviews14-16.

In this study, inmates from North Africa had a CHB rate of 1.6%, which is slightly lower than the one for their geographical area (1.8-4.9%)14, probably because most of the North Africans in the study were from Morocco, which is the North African country with the lowest prevalence (<2%)15. As was expected, prevalence was high (3%) amongst Asian inmates, given that three quarters of the world’s population with CHB live in Asia16, although the situation in this area appears to have improved in recent years thanks to more frequent implementation of vaccination programmes17.

Finally, there was a prevalence of 4.4% amongst inmates from former Eastern Europe, which matches the prevalence in the community18, and 14.1% amongst patients from Sub-Saharan Africa, which is higher than the estimates for this region, which are 4.6-8.5%19.

The total prevalence (1.7%) is lower than the one obtained from studies in 1990, which was 7.5%, and studies completed in 2011 and 2014, which showed a prevalence of 2.6% (Figure 4). However, although this data also comes from research carried out in a prison setting, the characteristics of the population studied and the methodology are not strictly comparable and so the data should be assessed with some degree of caution.

Figure 4. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus amongst inmates in Catalonia according to the total population (Spanish and foreign) in previous research and in this study.

Although different factors played a part in the reduced prevalence of infection, such as changes in the consumption patterns of drug users or increased use of protection in sexual relations, we believe that the protective factor with the greatest impact has been anti-HBV vaccination. The first pilot vaccination programmes in Catalonia for inmates began in 199320,21, and the effects have been notable, as the results of this study show. The effectiveness of the vaccine is unquestionable, and has been amply demonstrated in studies that include the entire population7,22 and in groups with a higher risk of infection: health workers23, persons with IDU24 and inmates25.

The protection offered by the vaccine is calculated to be 98-100%1, which has led to major epidemiological changes. For example: although persons with IDU are high-risk populations for HBV transmission, this group, which was vaccinated an masse in Catalan prisons from the 1980s onwards7,22,24, has been mostly immunised, and presents no higher prevalence of CHB than in the non-IDU population. Vaccination is also probably contributing towards reducing infection amongst foreign inmates. This is suggested in the evolution of infection in this group, where the rate has gone down by 31.6% in the last seven years, dropping from 3.813 to the present figure of 2.6%. Vaccination is therefore an essential strategy, and major efforts should be made in this regard, since calculations have been made that show that when vaccination coverage is over 70%, the reduction of incidence is up to two times higher than when coverage is lower22.

In this study, the prevalence of CHB in the prisons was not uniform and was logically higher in provincial centres such as Puig de les Basses, Brians-1 and Mas d’Enric, which house pre-trial (recently detained) inmates and therefore have a larger number of vaccinated or unvaccinated entrants and a larger proportion of foreign inmates.

As regards age and gender, a higher prevalence of CHB was observed amongst men and in the age range of 22-59 years, which is also common in the general population. These findings reflect the data compiled by the Spanish National Epidemiology Centre4 and the figures obtained by European26 and American27. centres for disease control and prevention

One notable finding is the absence of CHB amongst inmates under 21 years of age, probably because this group is much more likely to have been vaccinated, and this situation would apply both to Spaniards and to immigrants who came to Spain when they were children.

Another notable point is HIV infection, which is commonly associated with CHB, since both diseases share similar routes of transmission. According to data from the Consensus Document of the Aids Study Group (GESIDA)/Viral Hepatitis Study Group (GEHEP), the prevalence of infection with HBV amongst persons infected with HIV in Spain has gone down in recent years and stood at 2.5% in 202128.

It should also be noted that HIV infection amongst inmates in Catalonia is six times more prevalent than in the community, after making adjustments for sex and age29.

In this study, the persons infected with HIV, who in prison are mostly IDUs, are three times more likely to be infected with HBV. It should be pointed out that those coinfected with HIV-HBV are older, and many probably acquired the HBV infection in the pre-vaccination period, given that coinfection amongst younger IDUs is significantly less frequent, since they are often immunised. Another notable feature is that all the coinfected subjects are receiving anti-HBV therapy, as they have access to combinations of antiretroviral drugs that include medications with anti-HIV and anti-HBV activity. In our case, all the coinfected patients were being treated with tenofovir alafenamide and emtricitabine, since treatment is usually prescribed regardless of the levels of alanine aminotransferase, HBV-deoxyribonucleic acid and the level of cellular injury, which are parameters that indicate the need (or not) for prescriptions in non-coinfected individuals30.

However, the rate of treatment of non-coinfected inmates was much lower, probably because treatment is not always indicated in such cases, or only in some phases and also because staging can also require 6-12 months for correct classification9, which means that many inmates are released before staging is completed. Even so, the rate of treatment amongst non-coinfected patients appears to be low, and may well be an issue that the Catalan prison services should focus on and improve.

This study has some limitations. It takes information from the databases of participating clinical services, and this type of research is economical, reduces biases in measurements and reproduces real life. But it does have a disadvantage in that the analysed variables have to be the ones that can be obtained from the databases. This made it impossible to gather information about high-risk sexual behaviour, which in the clinical record is sometimes omitted or not effectively gathered.

However, we consider the other errors related to data collection to be unlikely, since most of the variables that were analysed were not interpretative but mainly analytical. Other biases, such as possible under-reporting, which are common in this type of research, are in our opinion of little importance in this study, since there is universal screening of some infections when entering prison, and the coverage in HBV screening is over 90%.

By way of conclusion, the prevalence of CHB amongst inmates in Catalonia has sharply reduced, but is still high amongst immigrants, especially in the North Africa, Asian and Sub-Saharan populations, those infected by HIV and inmates that have not been vaccinated.

Prison medical teams can and should play a fundamental role in preventing and eliminating HBV. To do so, it is essential to detect infections, apply preventive measures, evaluate and treat infected patients, and maintain epidemiological surveillance programmes.

We recommend the following: a) maintain screening for HBV and other highly prevalent infections amongst inmates when they enter prison; b) continue with current vaccination programmes, which have reduced the rate of CHB amongst inmates and also in the community; and c) refer detected cases of CHB to specialised control and monitoring programmes.