My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones

On-line version ISSN 2174-0534Print version ISSN 1576-5962

Rev. psicol. trab. organ. vol.25 n.2 Madrid Aug. 2009

Breaking Negative Consequences of Relationship Conflicts at Work: The Moderating Role of Work Family Enrichment and Supervisor Support

Rompiendo las Consecuencias Negativas del Conflicto de Relación en el Trabajo: El Rol Moderador del Enriquecimiento Trabajo-Familia y el Apoyo del Supervisor

Marina Boz1, Inés Martínez2, Lourdes Munduate1

1Department of Social Psychology, University of Seville, Seville, Spain

2Department of Psychology, University Pablo de Olavide, Seville, Spain

RESUMEN

The negative consequences of relationship conflict in organizations are well-known. Nevertheless, research concerning possible moderators that could attenuate its detrimental effects is still scarce. The present study aimed to fill this gap by addressing work-family enrichment and supervisor support as moderators of relationship conflict. The study involved 288 employees from small and medium companies from Andalusia (Spain). Consistent with previous evidence, results demonstrate a strong and negative association between relationship conflict and job satisfaction. However, work-family enrichment and supervisor support revealed to play a key role in buffering this effect, so that for employees that perceive a supportive supervisor and an enriching work environment, the negative consequences of relationship conflict on job satisfaction are not so damaging.

Palabras clave: relationship conflict, work-family enrichment, supervisor support, job satisfaction.

ABSTRACT

Las consecuencias negativas del conflicto de relación en las organizaciones son ampliamente conocidas. Sin embargo, se han llevado a cabo escasas investigaciones sobre los posibles moderadores que podrían atenuar sus efectos perjudiciales. El presente estudio trata de suplir este vacío examinando el enriquecimiento trabajo-familia y el apoyo del supervisor como moderadores del conflicto de relación. La muestra estuvo compuesta por 288 empleados y empleadas de pequeñas y medianas empresas de Andalucía (España). Consistentes con la evidencia previa, los resultados demuestran una fuerte y negativa asociación entre el conflicto de relación y la satisfacción en el trabajo. Sin embargo, el enriquecimiento trabajo-familia y el apoyo del supervisor revelaron que juegan un papel clave en amortiguar este efecto, de tal modo que para los empleados que perciben un supervisor que les apoya y un ambiente de trabajo enriquecedor, las consecuencias negativas del conflicto de relación sobre la satisfacción en el trabajo no son tan dañinas.

Key words: conflicto de relación, enriquecimiento trabajo-familia, apoyo del supervisor, satisfacción laboral.

Conflict is an intrinsic process in the dynamics of teams and organizations, as it is present in interpersonal relations, intragroup and intergroup relations, in strategic decision-making, and other organizational episodes (Medina, Munduate, Dorado, Martínez, & Guerra, 2005). As noticed by De Dreu and Weingart (2003), team members are constantly contributing to teams through social and task inputs, so that it can be expected that some tension between team members due to real or perceived differences will arise occasionally. These differences can be related either to tasks or to personal relationships in itself. Accordingly, research distinguishes between two types of conflict: task conflict and relationship conflict (Jehn, 1995).

Jehn and Mannix (2001) defined relationship conflict as an awareness of interpersonal incompatibilities that includes affective components such as feeling tension and friction. According to the authors, relationship conflict involves personal issues such as dislike among group members and feelings such as annoyance, frustration, and irritation. This definition is consistent with past categorizations of the affective type of conflict, referred to as personal incompatibilities and disputes (Amason, 1996). Examples of relationship conflict are disagreements about values, norms, preferences, personal and familiar tastes, among others.

It is very unlikely that relationship conflict would be beneficial at any point in the life of a group (Jehn & Mannix, 2001). Cross-sectional studies using one-time measures have shown that relationship conflict is detrimental to individual and group performance, member satisfaction, and the likelihood a group will work together in the future (Jehn, 1995). Relationship conflict has demonstrated to increase stress levels (Friedman, Tidd, Currall, & Tsai, 2000) and propensity to leave the job (Medina et al., 2005), produce negative reactions such as anxiety, depression, and frustration (Spector & Jex, 1998), reduce levels of job satisfaction (De Dreu & Van Vianen, 2001) and wellbeing (Guerra, Martínez, Munduate, & Medina, 2005). Research findings indicate that anxiety produced by interpersonal animosity may inhibit cognitive functioning (Roseman, Wiest, & Swartz, 1994; Staw, Sandelands, & Dutton, 1981) and also distract employees from the task, causing them to work less effectively (Jehn, 1997).

In a meta-analytic study, De Dreu and Weingart (2003) found that relationship conflict appears to always exert a more negative effect than task conflict does even though both types of conflict (task and relationship) showed to have a negative effect on several individual, group and organizational outcomes. Indeed, relationship conflict tends to be more interpersonal and emotional, thus more likely to elicit a negative affective response and, consequently, strongly interfere in several outcomes.

Relationship conflict and job satisfaction

As mentioned above, the existing literature provides strong support for the negative impact that relationship conflict plays in affective reactions in workplaces. When analyzing the effects of relationship conflict on affective outcomes, several authors pay special attention to the effects on employee’s job satisfaction (Guerra et al., 2005; Medina et al., 2005). The reason for highlighting this variable is because, on one hand, satisfaction is an important predictor of individual’s well-being and health and, on the other hand, is a predictor of several organizational outcomes such as performance (Spector & Jex, 1998), turnover, absenteeism, and organizational citizenship behavior (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003).

Moderators of relationship conflict

Relationship conflict is often conceived as detrimental to individual affective outcomes, but research has ignored the question what to do when relationship conflict emerges (De Dreu & Van Vianen, 2001). De Dreu and Weingart (2003) pointed to the need of exploring possible moderators that could potentially mitigate or reverse the negative effects of relationship conflict. When relationship conflict emerges, individual satisfaction is at risk, and resources to mitigate and eliminate this type of conflict are needed. In this sense, the current study was conducted to fill this void by examining potential moderators of the link between relationship conflict and job satisfaction.

According to Jehn (1997), relationship conflict causes members to be irritable, negative, suspicious and resentful. In a study about interpersonal relationships in groups, she found that when group members are upset, feeling antagonistic towards each other and experiencing affective conflict, their performance, productivity, and satisfaction can suffer. Jehn posits that this might happen because in a relationship conflict situation, group members will tend to focus their efforts on resolving or ignoring the interpersonal conflicts, rather than concentrating on task completion. Then, relationship conflicts can be seen as unproductive, hard to manage, and likely to leave people with more pressures and less ability to manage them.

In this sense, some studies analyzed the relationship conflict as one of the most important workplace stressors (Frone, 2000; Giebels & Janssen, 2005; Spector & Jex, 1998). Friedman et al. (2000) found that high levels of relationship conflict affected the amount of stress felt by individuals. Giebels and Janssen posited two main factors that might explain the close bond between relationship conflict and feelings of stress. Firstly, conflict is often perceived as an obstruction to one’s goals, triggering feelings of reduced control and uncertainty, considered important prerequisites of a stress response. Second, relationship conflict can threaten one’s self-esteem and sense of group membership by undermining one’s sense of self and similarity to others, consequently being stressful in itself. Thus, in terms of the occupational stress literature, a relationship conflict episode can be considered an acute job stressor (Spector & Jex, 1998).

In stress appraisal situations, stress-reducing properties of resources play a major role that should always be taken into consideration for an effective and positive coping (Carver & Scheier, 1994). Resources are assets that may be drawn on when needed to solve a problem or cope with a challenging situation. Accordingly, two main types of resources can be distinguished (Friedman et al., 2000): (a) instrumental resources such as financial means, social and problemsolving skills, and (b) emotional resources such as selfesteem, energy, among others. In this mean, individuals involved in stressful situations such as a relationship conflict could benefit from the same resources in order to cope and reduce the negative effects of conflict. Following this reasoning, in the present study we propose two instrumental and emotional resources as possible moderators of the link between relationship conflict and job satisfaction: work-family enrichment and supervisor support.

The work environment potentially provides individuals with a variety of organizational and individual resources such as skills, perspectives, socio-capital, psychological and material resources (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Work-family enrichment is the perception that the work role provides individuals with instrumental and affective resources that help them to improve affect and performance in their family domain (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). These resources refer to the two main components of work-family enrichment, one more instrumental, related to skills, abilities, and values, and another more affective, related to climate, mood, and emotions (Carlson, Kacmar, Wayne, & Grzywacz, 2006). In this sense, one could think that besides having a main effect on individual affect and performance in their family domain, these resources could help individuals to successfully cope when facing stressful situations at work such as relationship conflicts.

In fact, work-family balance has already been considered as a possible moderator of the relationship between stressors and its effects (William & Cooper, 1998). On the other hand, in the work-family literature, Greenhaus and Powell (2006) proposed that work-family enrichment could serve a buffering role that protects and individual from the negative consequences of a stressor, nevertheless this hypothesis has not been demonstrated yet. Carlson et al. (2006) suggest that when individuals perceive extensive resources in their work role, their positive affect in that role increases and so do their affective resources such as satisfaction.

Thus, assuming that (a) relationship conflict is a stressful situation, (b) the perception of work-family enrichment provides individuals with multiple resources to cope with stress, and (c) the perception of work-family enrichment leads to job satisfaction, we expect the perception of work-family enrichment to exert a buffering effect on the negative consequences of the relationship conflict over job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1: The higher the levels of work-family enrichment are, the less negative the relationship between relationship conflict and job satisfaction is.

Stressful situations such as relationship conflict are related to feelings of helpless and threat of self-esteem. In this sense, different types of social support such as instrumental and informational support, esteem, and social companionship have demonstrated to reduce these negative effects (Cohen & Wills, 1985). According to Viswesvaran, Sanchez, and Fisher (1999) meta-analysis, models of moderator effects of social support on the stressor–strain relationship have been postulated and empirically investigated. Several studies have found evidence for buffering effects of social support in the detrimental effects of organizational stressors on personal functioning (Etzion, 1984; Kirmeyer & Dougherty, 1988).

In the stress literature, supervisor support is a source of social support, which is generally defined as “the availability of helping relationships and the quality of those relationships” (Leavy, 1983, p.5). Supervisors have long been recognized to play an important part in developing roles and expectations of employees (Griffin, Patterson & West, 2001). As a consequence, supervisors' behaviors have demonstrated to directly impact on the affective reactions of his or her subordinates. Supervisor support is the extent to which supervisors provide encouragement and support to employees within their work groups (Griffin et al., 2001). Evidence suggests that supportive supervisors facilitate employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Parasuraman, Greenhaus, & Granrose, 1992) and positively influence their performance and citizenship behavior (Schaubroeck & Fink, 1999).

Some researches have argued that social support buffers the detrimental effects of stressors by enhancing successful coping (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Kobasa & Puccetti, 1983). In this sense, we could expect supervisors' support to reduce the effects of relationship conflict by helping individuals to cope in this type of stressful situation. According to Kirmeyer and Dougherty (1988), supervisors may help subordinates to cope with stress in potentially stressful environments in three ways: (a) by keeping them task oriented and focused on the resolution of problems as opposed to being preoccupied with feelings and anxiety; (b) by encouraging them to take specific actions aimed at effectively reducing conflict; and (c) by assuring them of backing for their actions. In addition, Ury (1991) posits that the overall aim of supervisor support would be to minimize adverse emotional responses when encountering relationship conflict situations. The same author suggests two main strategies for supervisors to achieve this aim. At first, Ury proposes that supervisors can set specific norms and rules that can serve to reduce the freedom to express emotion in inappropriate ways, reducing the likelihood of an affective-conflict episode. In addition, he proposes that supervisors can also give employees emotional advises and support in order to encourage them to monitor their emotions. Basically, a supervisor can reduce instances of aggression and hostility by discouraging such behaviors, reprimanding inappropriate, emotionally driven outbreaks, and clearly specifying the rules of conduct.

Supervisors play a key role in structuring the work environment, because they are considered the main source of information and feedback to employees (Griffin et al., 2001). As a consequence, supervisors have a direct influence on the affective reactions of employees, such as job satisfaction. Moreover, supervisors are not only part of, but also facilitate the social network individuals build in their work settings, which in turn provide them with positive experiences, feel ings of self-worth and sense of stability and recognition (Cohen & Wills, 1985).

To sum up, we propose that (a) relationship conflict is a stressful situation; (b) supervisor support helps individuals with an effective coping; and (c) supervisor support increase levels of job satisfaction. So, following this reasoning, we expect supervisor support to exert a buffering effect on the link between relationship conflict and job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2: The higher the levels of supervisor support are, the less negative the relationship between relationship conflict and job satisfaction is.

Method

Procedure and Sample

A public organization provided us with access to the sample consisted of employees from small and medium companies in Andalusia (Spain). After receiving proper training, assistants from this organization applied the questionnaires to volunteer participants from different professional categories and working in a diverse range of economic activities. The anonymity was guaranteed.

The study involved 288 participants (167 female, 121 male) on average age of 35.41 years old. More than a half of the participants (76.2%) are married or cohabiting, and 64.7% have children. Of the participants with children, 55.13% had a youngest child of pre-school age (0 - 3 years old). About 67.9% of participants do not count on regular homecare and only 9.6% count on familiar support. About half of the participants (64.1%) received higher education (university or higher vocational education) while 55.9% had only completed lower education (lower vocational education or high school). Regarding the wage range, 35.6% earns up to 1.200 euros, 47.6% earns between 1200 to 2100 euros and only 16.7% earns more than 2100 euros monthly. The average wage in Spain consists of 2113 euros gross and 1538.17 net (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2008), so that we conclude that the wage range from the majority of participants in this sample is below the national standards. About half of the participants have some type of temporary labor contract (51.5%) and belong to a blue collar professional category (60.9%). The average organizational tenure was 10.56 years (range 0 - 48, SD = 7.83).

Instruments

Relationship conflict. ASpanish adaptation of Cox’s (1998) “Organizational Conflict Scale” to assess relationship conflict was used (Medina et al., 2005). Cox’s scale focuses on the active hostility found in relationship conflict. The original items are: “The atmosphere here is often charged with hostility”, “Backbiting is a frequent occurrence”, “One party frequently undermines the other”, “There are often feelings of hostility among parties” and “Much plotting takes place behind the scenes”. We used this scale because it deals more with perceptions of active conflict behaviors rather than perceptions of an overall state of conflict (see Friedman et al., 2000). The scale has a 5-point response format (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The higher the score is, the higher the levels of relationship conflict are experienced (a.89).

Work-family enrichment. A Spanish adaptation of the 9-item subscale of work interference with family was used, which is a component of the “Work-Family Enrichment Scale” (Carlson et al., 2006). This subscale measures the following dimensions of work-tofamily enrichment: development (3 items) (e.g. “My involvement in my work helps me acquire skills and this helps me be a better family member”), affect (3 items) (e.g. “My involvement in my work puts me in a good mood and this helps me be a better family member”), and capital (3 items) (e.g. “My involvement in my work provides me with a sense of accomplishment and this helps me be a better family member”). The scale uses a 5-point response format (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores on this scale represent higher work-family enrichment ( a = .94).

Job satisfaction. It was used a 5-item Spanish version from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss, Dawis, England, & Lofquist, 1965) adapted to Spanish by Peiró et al. (1993). This scale measures employee’s level of satisfaction with some extrinsic aspects of their jobs, as well as the general job satisfaction. The original items are: “My pay and the amount of work I do”, “The way my job provides for steady employment”, “The way my co-workers get along with each other”, “The competence of my supervisor in making decisions” and “Overall, how satisfied are you with your job?”. The scale uses a 5-point response format (1 = not satisfied, 5 = very satisfied) (a = .70).

Supervisor support. It was measured with the 4-item Spanish version of the supervisor support scale from Karasek et al. (1985). This scale measures employees’ perceived instrumental and socio-emotional support from supervisors. The original items are: “My supervisor is concerned about the welfare of those under him/her”, “My supervisor pays attention to what I’m saying”, “My supervisor is successful in getting people to work together” and “My supervisor is helpful in getting the job done”. The scale uses a 4-point response format (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) (a = .90).

Controls. In line with previous research involving work-family enrichment (e.g Wayne, Musisca, & Fleeson, 2004), we measured some demographic factors: gender (0 = male; 1 = female), age (in years), marital status (1 = married / cohabiting; 2 = single, divorced or widowed), children living at home (0 = no, 1 = yes), education (1 = lower vocational education or high school; 2 = university or higher vocational education), working hours (contractual hours per week), type of contract (1 = permanent; 2 = temporary), wage range (1 = less 1200 euros per month; 2 = between 1200 and 2100 euros per month; 3 = more than 2100 euros per month) and organizational tenure (in years).

Results

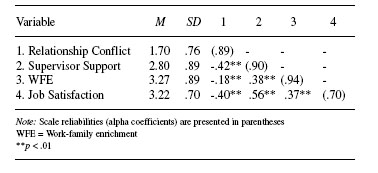

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among variables. As we expected, relationship conflict is negatively related to all other dependent variables. In addition, unexpectedly, relationship conflict is also negatively related to workfamily enrichment (r = -.18, p < .01); this result is further discussed. Moreover, supervisor support is positively related to enrichment and job satisfaction. Finally, enrichment and job satisfaction share a significant but moderated relationship. Additionally, we assessed the internal consistency reliability of all the behavioral variables using Cronbach’s alpha. As can be seen in Table 1, the reliability coefficients were good to excellent.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations for all variables (N = 288)

We measured demographic variables that may affect our dependent variables. In order to examine differences regarding the controls, we conducted a MANOVA on the supervisor support, work-family enrichment, relationship conflict and job satisfaction scales (including the controls as factors). We found differences for work-family enrichment and job satisfaction only. Specifically, women (F (1, 283) = 13.04, p < .001; Female M = 3.43 vs. Male M = 3.05) and employees with a temporary contract (F (2, 279) = 3.01, p < .05; Temporary contract M = 3.51 vs. Permanent contract M = 3.09) reported higher levels of work-family enrichment. Regarding job satisfaction, we found that employees with children living at home (F (1, 281) = 3.99, p < .05; With children M = 3.28 vs. Without children M = 3.11) and employees earning more than 2100 euros per month (F (2, 272) = 3.46, p < .05; More than 2100 euros per month M = 3.43 vs. Between 2100 and 1200 euros per month M = 3.23 vs. Less than 1200 euros per month M = 3.11) reported higher levels of job satisfaction. Then, for testing our hypotheses we have controlled for gender, type of contract, children living at home and wage range in the regressions conducted. Results are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

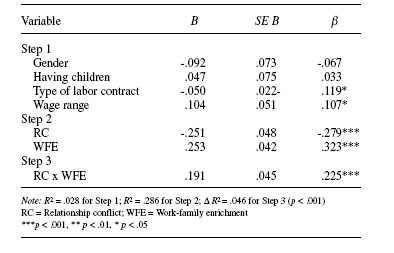

Table 2. Effect of Relationship Conflict on Job Satisfaction

moderated by Work-Family Enrichment (N = 283)

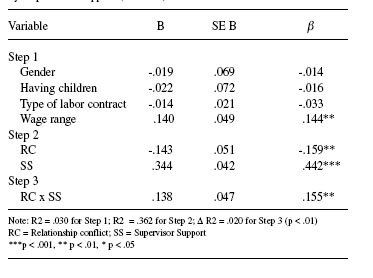

Table 3. Effect of Relationship Conflict on Job Satisfaction moderated

by Supervisor Support (N = 283)

A simple regression analysis was performed in order to test the link between relationship conflict and job satisfaction ( b= -.422, p < .001). This effect indicates a strong negative association between relationship conflict and job satisfaction, high levels of relationship conflict is related to low levels of job satisfaction. This finding agrees with previous evidence.

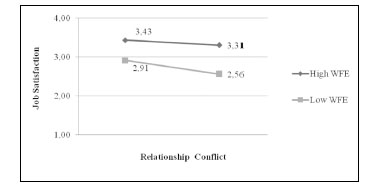

Our first hypothesis suggested a moderating effect of work-family enrichment between relationship conflict and job satisfaction. This hypothesis was tested using hierarchical linear regression. All variables used to compute the regression equation were mean centered in order to reduce the multicollinearity between the main effect and the interaction variables (Aiken & West, 1991). The interaction term was a product of mean centered relationship conflict and work-family enrichment. In Step 1 control variables were entered as covariates. Mean relationship conflict and mean workfamily enrichment were entered in Step 2, which yielded a significant R2 for job satisfaction. As expected, the interaction term after the two main effects variables yielded a significant Δ R2 (see Table 2). In order to test the significance of the slope for this interaction term, we computed a simple slope test following Cohen and Cohen’s (1983) procedure. Accordingly, the interaction slope was significant for high levels of the moderator variable, i.e. at the mean (M = 3.27, p < .05) and at one SD above the mean of work-family enrichment (4.16, p < .01). As can be seen in Figure 1, job satisfaction increases when high relationship conflict is combined with work-family enrichment whereas it decreases when high relationship conflict is combined with low work-family enrichment. This finding supports our first hypothesis.

Figure 1. Relationship conflict, work-family enrichment (WFE)

and job satisfaction

Our second hypothesis suggested a moderating effect of supervisor support between relationship conflict and job satisfaction. This hypothesis was also tested using hierarchical linear regression with mean centered variables. In Step 1 control variables were entered. Mean relationship conflict and mean supervisor support were entered in Step 2, which yielded a significant R2 for job satisfaction. As expected, the interaction term obtained from the product between mean centered relationship conflict and supervisor support yielded a significant Δ R2. This regression analysis is presented in Table 3. Accordingly, the interaction slope was significant for high levels of the moderator variable, i.e. at two SD above the mean of supervisor support (4.58, p < .05). As can be seen in Figure 2, job satisfaction increases when high relationship conflict is combined with high supervisor support whereas it decreases when high relationship conflict is combined with low supervisor support. This finding supports our third hypothesis.

Figure 2. Relationship conflict, supervisor support and job satisfaction

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to analyse possible moderators that could mitigate the negative effects of relationship conflict on individuals' satisfaction. The main findings show, first, the effects of relationship conflict on job satisfaction and second, the moderating role that work-family enrichment and supervisor support plays in this relationship. In this section we discuss the implications of these findings, and examine some strengths and weaknesses of the study design.

As envisaged, relationship conflict hampers satisfaction of employees. In other words, when employees working together have incompatible values, beliefs and ideas, personal tension emerges, and workers' levels of satisfaction decrease. This result is consistent with previous findings (De Dreu & Van Vianen, 2001; Surra & Longstreeth, 1990). As Kurtz and Clow (1998) suggested, these affective reactions of employees have important consequences for organizational dynamics, because “unsatisfied employees can cost companies more than the wages they are paid” (p. 173). Moreover, the study of organizational culture suggests that relationship conflict has a negative impact on daily working practices. This is because employees who perceive a high relationship conflict have a negative perception of the organization and of the activities being performed within it. Finally, drawn on the stress perspective, the negative emotionality resulting from a relationship conflict situation directly affects a successful coping, which in turn contribute to a decrease of employees' satisfaction.

Nevertheless, our study also demonstrates that, under certain circumstances, the negative consequences of relationship conflict over job satisfaction can be reduced. Specifically, we found that in a relationship conflict situation, individuals who perceive high levels of work-family enrichment and supervisor support present higher levels of job satisfaction compared to individuals who perceive low levels these resources. We attribute this effect mainly to the high affective component of both constructs. Because the relationship conflict is an affective type of conflict, mainly based in negative emotions such as annoyance, frustration and irritation, we posit that the positive affect embedded in the work-family enrichment and supervisor support perceptions can be highly effective in helping individuals to cope when facing a relationship conflict at work. In this sense, previous research on stress processes and coping have already demonstrated that people consciously seek out for positive emotions during stressful encountering in order to increase their positive affect, which in turn helps individuals to reduce distress and recover and sustain further coping (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004).

Specifically, some studies have demonstrated the importance of affective resources in dealing with relationship conflict situations. For example, Mooney, Holahan and Amason (2007) found that individuals that have a good relationship with their colleagues are less likely to engage in relationship conflict. In addition, Jehn and Mannix (2001) found that employees part of friendship groups characterized by a friendly climate and high levels of trust and cooperation, present low levels of relationship conflict. These findings indicate that individuals that appraise positively their work environment and consequently perceive workfamily enrichment might feel more self-confident to cope in stressful situations because of the multiple resources they acquired from their work environment. The negative relationship found between relationship conflict and work-family enrichment might lead us to think that relationship conflict could reduce individual’s perception of work-family enrichment. However, the negative intercorrelation found does not represent a direct effect. Moreover, some authors suggest that the perception of work stressors, such as relationship conflict, not necessarily hinder individual’s experience of work-family enrichment (Powell & Greenhaus, 2006), and that negative and positive experiences in the work environment might coexist.

Finally, this study confirms that supportive supervisors play a key role in alleviating the negative effects of relationship conflict on job satisfaction, adding evidence to the buffering effect model of social support on stressor-strain relationship (see Viswesvaran et al., 1999). The buffering model posits that social support may attenuate a stress appraisal response. The instrumental and socio-emotional resources provided by supervisors may “redefine the potential for harm posed by a situation and/or bolster one’s perceived ability to cope, with imposed demands, and hence prevent a particular situation from being appraised as highly stressful” (Cohen & Wills, 1985, p. 312). In this sense, supervisor support may alleviate the negative consequences of a stressful situation by providing solution to a problem, reducing the perceived importance of the problem or tranquilizing individuals to be less reactive to stress.

Therefore, we conclude that individuals encountering a relationship conflict situation at work are not condemned to overall present negative perceptions of their work environment. The moderating effect of work-family enrichment and supervisor support on the consequences of relationship conflict found in this article opens an interesting line for future research on coping with relationship conflict situations. As we mentioned before, empirical evidence suggesting possible moderators for the relationship conflict is still sparse (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003). In the organizational conflict literature, even though relationship conflict has consistently demonstrated to exert a negative effect on employees' attitudes and emotions, the efforts to find possible factors that could attenuate its negative effects have been widely unexplored. Nevertheless, the present study draws upon alternative individual factors that could possibly reduce the negative effects of relationship conflict in the employees' satisfaction. In this sense, future studies should consider the role of other individual resources that have demonstrated to contribute for an effective coping in the stress-strain relationship, such as self-efficacy (Grau, Salanova & Peiró, 2001) and emotional self-control (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004).

This study also makes two specific contributions to the stress literature. First, by analyzing the relationship conflict as a stressor, this study contributes to increase empirical evidence regarding less common job stressors, i.e., the ones found in the employee’s social environment. Social-related stressors have been underexplored compared to task-related stressors. Second, by demonstrating the influence of positive emotion for an effective coping in a stressor-strain relationship, the present study adds to a mayor trend in the stress process and coping research, which is to focus on positive traits and concepts (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004).

Some practical implications from the present study concern the improvement of conflict management in the organizational setting. First, relationship conflict is an affective conflict, so that when managing this type of conflict, one should always consider the fundamental role of emotional-based resources such as workfamily enrichment, in order to reduce negative emotions associated with it. Second, in a relationship conflict situation, supervisors should demonstrate support to their employees. This support can consist of actions to prevent and intervene in a relationship conflict situation. In order to prevent a relationship conflict situation to emerge, supervisors are expected to control the levels of aggressiveness and animosity among employees. Finally, in order to intervene in an encountering relationship conflict episode, supervisors can promote certain norms and rules of conduct related the decision- making process that can help to manage expectations as well as to reduce adverse emotions arising from a conflict situation.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, we obtained self-reported measures of members’ perceptions, and, as a consequence, there is a possibility of common method variance. However, this risk was reduced by using standardized instruments and analyzing interactions as the present study did (Spector, 1987). Second, because we used a cross-sectional design, we cannot assure the stability of these apparently positive results over time. Finally, we should point out that the use of a correlational methodology does not guarantee the existence of causal links between the studied variables. It would therefore be of interest to perform experimental studies to analyse whether these results are further upheld.

Taken together, our results confirm that relationship conflict situations might directly reduce employees’ job satisfaction. However, if employees experience high levels of affective and instrumental resources at work that can help them perform better at home and also feel that their supervisor is supportive of them, this relationship is attenuated.

Bibliografía

Aiken, L. S. & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Amason, A. C. (1996). Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making: resolving a paradox for top management groups. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 123–148. [ Links ]

Carlson, D.S., Kacmar, K.M., Wayne, J.H., & Grzywacz, J.G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work-family interface: development and validation of a work-family enrichment scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 131-164. [ Links ]

Carver, C.S. & Scheier, M.F. (1994). Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 184-195. [ Links ]

Cohen, J. & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlationanalysis for the behavioral sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Cohen, S. & Wills, T.A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310-357. [ Links ]

Cox, K. B. (1998). Antecedents and effects of intergroup conflict in the nursing unit. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA. [ Links ]

De Dreu, C. K. W. & Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2001). Responses to relationship conflict and team effectiveness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 309-328. [ Links ]

De Dreu, C. K. W. & Weingart, L.R. (2003). Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 741-749. [ Links ]

Etzion, D. (1984) Moderating effect of social support on the stress-burnout relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 615-622. [ Links ]

Folkman, S. & Moskowitz, J.T. (2004). Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 745-774. [ Links ]

Friedman, R. A., Tidd, S. T., Currall, S. C., & Tsai, J. C. (2000). What goes around comes around: the impact of personal conflict style on work conflict and stress. International Journal of Conflict Management, 11, 32-55. [ Links ]

Frone, M.R. (2000). Interpersonal conflict at work and psychological outcomes: testing a model among young workers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 246-255. [ Links ]

Giebels, E. & Janssen, O. (2005). Conflict stress and reduced well-being at work: The buffering effect of third-party help. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14, 137-155. [ Links ]

Grau, R., Salanova, M., & Peiró, J.M. (2001). Moderator effects of self-efficacy on occupational stress. Psychology in Spain, 5, 63-74. [ Links ]

Greenhaus, J.H. & Powell, G.N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work and family enrichment. Academy of Management Journal, 31, 72-92. [ Links ]

Griffin, M.A., Patterson, M.G., & West, M.A. (2001). Job satisfaction and teamwork: the role of supervisor support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 537-550. [ Links ]

Guerra, J.M., Martínez, I., Munduate, L., & Medina, F.J. (2005). A contingency perspective on the study of the consequences of the conflict types: the role of organizational culture. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14, 157-176. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) (2008). Encuesta Trimestral de Coste Laboral (Quarterly Labor Costs Survey)..Retrieved July 15 2009, from INE Website: http://www.ine.es/INEBASE/temas/tmp/ETCLhist2.html [ Links ]

Jehn, K.A (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 256–282. [ Links ]

Jehn, K.A (1997). “A qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions in organizational groups”. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 530-557 [ Links ]

Jehn, K.A. & Mannix, E. (2001). The dynamic nature of conflict: A longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 238-251. [ Links ]

Karasek, R.A., Gordon G., Pietrokovsky, C., Frese M., Pieper C., Schwartz J., Fry L., & Schirer D. (1985). Job Content Instrument: Questionnaire and User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California. [ Links ]

Kirmeyer, S. L. & Dougherty, T. W. (1988). Work load, tension, and coping: moderating effects of supervisor support. Personnel Psychology, 41, 125-139. [ Links ]

Kobasa, S. C. & Puccetti, M. C. (1983). Personality and social resources in stress resistance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 45, 839-850. [ Links ]

Kurtz, D. L. & Clow, K. E. (1998). Services Marketing. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Leavy, R.L. (1983). Social support and psychological disorder: a review. Journal of Community Psychology, 11, 3- 21. [ Links ]

Medina, F.J., Munduate, L., Dorado, M.A., Martínez, I., & Guerra, J.M. (2005). Types of intragroup conflict and affective reactions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20, 219-230. [ Links ]

Mooney, A.C., Holahan, P. J., & Amason, A.C. (2007). Don’t take it personally: Exploring cognitive conflict as a mediator of affective conflict. Journal of Management Studies, 44, 733-758. [ Links ]

Parasuraman, S., Greenhaus, J., & Granrose, C. (1992). Role stressors, social support and well-being among twocareer couples. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 339-356. [ Links ]

Peiró, J.M., Prieto, F., Bravo, M.J., Ripoll, P., Rodríguez, I., Hontangas, P., & Salanova, M. (1993). Los jóvenes ante el primer empleo: El significado del trabajo y su medida, (“Young people before their first job: how to measure the signifcance of work”). Valencia: NAU llibres. [ Links ]

Powell, G. N., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2006). Is the opposite of positive negative? Untangling the complex relationship between work-family enrichment and conflict. Career Development International, 11, 650-659.Roseman, I., [ Links ]

Wiest, C., & Swartz, T. (1994). Phenomenology, behaviors and goals differentiate emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 206-221. [ Links ]

Schaubroeck, J. & Fink, L. S. (1999). Facilitating and inhibiting effects of job control and social support on stress outcomes and role behavior: A contingency model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 167-195. [ Links ]

Spector, P.E. (1987). Method variance as an artifact in selfreported affect and perceptions at work: myth or significant problems? Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 438-443. [ Links ]

Spector, P.E. & Jex, S.M. (1998). Development of four selfreport measures of job stressors and strain: interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3, 356-367. [ Links ]

Staw, B., Sandenlands, L., & Dutton, J. (1981). Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: a multilevel analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 501-524. [ Links ]

Surra, C. & Longstreeth, M. (1990). Similarity of outcomes, interdependence and conflict in dating relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 501-516. [ Links ]

Ury, W. L. (1991). Getting past no: Negotiating with difficult people. New York: Bantam. [ Links ]

Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J.I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A metaanalysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 314-334. [ Links ]

Wayne, J. H., Musisca, N., & Fleeson, W. (2004). Considering the role of personality in the work-family experience: Relationships of the big five to work-family conflict and enrichment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64, 108-130. [ Links ]

Weiss, D.J., Dawis, R.V., England, G.W., & Lofquist, L.H. (1965). Construct validation studies of the Minnesota importance questionnaire. Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation, XVIII. [ Links ]

Williams, S. & Cooper, C.L. (1998). Measuring occupational stress: development of the pressure management indicator. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3, 306-321. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Marina A. Boz

Department of Social Psychology

University of Seville

C/ José Camilo Cela, s/n

41018, Sevilla, Spain

Phone +34 954557735

Fax +34 954557711

Email: marandboz1@alum.us.es

Fecha de Recepción: 12/05/2009

Fecha de Aceptación: 14/07/2009