Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones

versión On-line ISSN 2174-0534versión impresa ISSN 1576-5962

Rev. psicol. trab. organ. vol.27 no.2 Madrid ago. 2011

The Generational Effect on the Relationship between Job Involvement, Work Satisfaction, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

El Efecto Generacional sobre la Relación entre Implicación en el Puesto, Satisfacción Laboral y Conducta Cívica

Dina Shragay and Aharon Tziner1

Netanya Academic College

ABSTRACT

In recent years, generational differences have been studied in the context of the workplace. In a review of the evidence for generational differences in work values, for example, Twenge (2010) reported that work centrality and the work ethic declined steadily from the Baby Boomer generation through Generation X and to Generation Y. However, although the literature appears to confirm that generational differences indeed exist in respect to work, very little research attention has been paid to the relationships between various work attitudes in the generational context. The current study therefore sought to examine the degree of generational influence on the relationships between three work-related attitudes and behaviors: work satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). The findings indicate that generation mitigates the effect only job involvement on two dimensions of OCB with the effects of this interaction being more positive among Gen X than Gen Y employees. The implications of the results were discussed and future research venues were suggested.

Keywords: generational differences, job involvement, job satisfaction, organizacional citizenship behavior, work attitudes.

RESUMEN

Las diferencias generacionales en el ámbito laboral ha sido tema de estudio en los últimos años. Por ejemplo, Twenge (2010) en una revisión sobre las diferencias generacionales en los valores en el trabajo, informó que la centralidad y la ética del trabajo se redujeron de manera constante desde la generación Baby Boomer y a través de la Generación X hasta la Generación Y. Sin embargo, aunque la literatura parece confirmar que realmente existen diferencias generacionales en el ámbito laboral, muy poca investigación se ha centrado en las relaciones entre actitudes laborales en el contexto generacional. El presente estudio examinó el grado de influencia generacional sobre las relaciones entre tres tipos de actitudes y conductas relacionadas con el trabajo: satisfacción laboral, implicación con el trabajo y conducta organizacional cívica. Los resultados indican que la generación mitiga únicamente el efecto de la implicación en el trabajo sobre dos dimesiones de la conducta organizacional cívica, siendo los efectos de esta interacción más positivos en los empleados de la Generación X que en los empleados de la Generación Y. Se discuten las implicaciones de los resultados y se hacen sugerencias para futura investigación.

Palabras clave: diferencias generacionales, implicación en el trabajo, satisfacción laboral, conducta cívica, actitudes laborales.

In order to understand generational differences, we must first define the notion of “generation” and establish a classification deriving from the typical characteristics of each generation. In terms of definition, Mannheim (1953) refers to a generation as “a group of people who were born and raised in a similar social and historical atmosphere,” whereas Kupperschmidt (2000) defines it as an identifiable group that shares years of birth and significant life events that occurred in critical stages of their lives. In other words, her categorization is both statistical and sociological, employing a variety of dimensions that represent significant historical events experienced by the group members, such as wars, catastrophes, or technological developments and significant innovations. On the basis of the literature, the Baby Boomers are defined in the current paper as people born between 1946 and 1964; Gen X as those born between 1965 and 1981 (Egri & Ralston, 2004); and Gen Y as those born after 1982 (Eisner, 2005).

Work-relevant characteristics of the three generations

The Baby Boomers. This generation was born into the economic growth that followed in the wake of World War II. They grew up in an optimistic and prosperous time, with the mantra of “sex, drugs and rock- 'n'roll” leading to a sense of “self containment” (taking care of themselves; Weil, 2008). Their fathers were the breadwinners and their mothers were housewives. They are known to be loyal, competitive, and workaholics (Crampton & Hodge, 2007), whose earnestness and devotion to their job was affected by the Vietnam War and economic prosperity (Patota, Schwartz, & Schwartz, 2007). They are willing to make sacrifices for their careers, believe that one should pay membership dues to the organization, and that “values” are related to work hours, promotion, size of office, and free parking (Kupperschmidt, 2000). Furthermore, the Baby Boomers saw numerous social changes in their youth, resulting in a willingness to accept change (Crampton & Hodge, 2007), and proved their resolve to fight for a cause. At work they value success, teamwork, and challenge, maintain a favorable relationship with their superiors, and acknowledge the importance of their colleagues (Karp, Fuller, & Sirias, 2001). Because of their emphasis on hard work and achievement, they value loyalty and commitment to the workplace. On the other hand, however, they encounter difficulties balancing their private lives and their work obligations (Lancaster & Stillman, 2002).

Generation X. The members of this generation are also known as Busters (Reisenwitz, 2009). Coming after the golden era of the Baby Boomers, Gen X was born into a challenging socioeconomic reality marked by an unstable economy, the outbreak of the AIDS epidemic, the end of the Cold War, and scandals involving organizations and governments. All this resulted in a lack of trust (Johnson & Lopes, 2008), leading to a tendency to rely on individual initiative and to develop independence and creativity. Neil (2010) notes that this generation was the first to be exposed to the mass media and technological breakthroughs. He claims that as both their parents worked, producing the concept of “latchkey kids,” Gen X is self-confident, independent, and dislikes supervision. Nevertheless, they have learned to accept and provide immediate and ongoing feedback. At work they seek self-satisfaction are capable of working in a multicultural environment, want to have fun, and have a practical approach to achieving results. Since many members of Gen X embarked on the labor market when the economy was at a low point, and grew up with parents who suffered the loss of their jobs and occupational insecurity, they redefined the concept of “work loyalty.” Instead of being loyal to the organization, they are loyal to their jobs and the colleagues and managers with whom they work, taking employment per se seriously but not committed to a career linked to a single organization. Rather, they move from place to place, stopping and beginning again (Neil, 2010).

Generation Y. This term was coined in 1993 by the magazine Advertising Age to refer to the last generation born in the 20th century. They are also known as the Echo Boomers, the Millennium Generation, and Generation Next (Reisenwitz, 2009). They were born into an era of globalization, media, and immediate technology. Children were at the center, with everything revolving around them. They received profuse attention, expectations from them were high, and their parents cultivated a large degree of self-confidence in them. They are group-oriented, join together at social events (parties, pubs, etc.) instead of separating into couples, and as a result they work well in groups and prefer teamwork to individual effort. Moreover, they are good at multitasking and work hard. They expect organizational structure, appreciate knowledge and status, and seek a relationship with the manager (which does not always work well with Gen X managers who prefer independence and individual work). As the new employees in the workplace, they are the generation most in need of mentoring, and in fact, they respond well to individual attention. However, since they appreciate structure and stability, they require a formal training program, a schedule, and reliable authority (Neil, 2010). In addition, they are highly aware of civic responsibility and are inclined to volunteer (Leyden, Teixeira & Greenberg, 2007), and are inquisitive, ask questions, and act in accordance with results (Streeter, 2007).

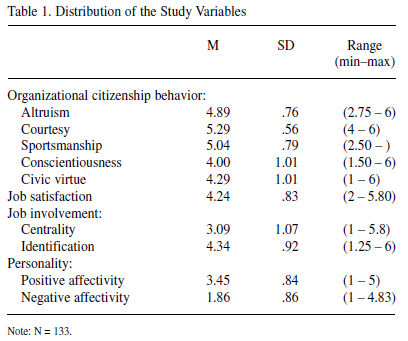

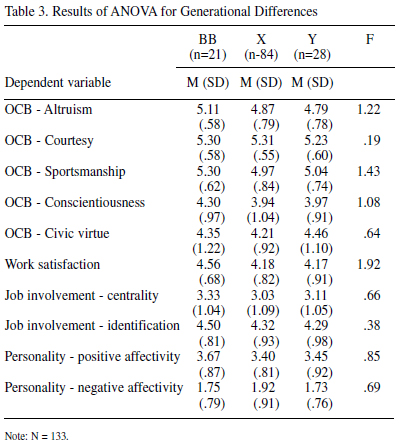

everal studies have considered the implications of these generational characteristics in the workplace. In a comprehensive review of both academic and popular publications aimed at producing a profile of each of the three generations, Whitney, Greenwood, and Murphy (2009) found considerable differences between them. The Boomers were found to hold senior positions in both the private and public sectors. They are typically industrious, object to authority, and feel that they have achieved their position by right. They can be motivated by money, extra time, promotions, and rewards for excellence, and can be expected to be loyal. Moreover, this generation initiates change and is willing to fight for a worthy public cause. Gen X, who will replace the Boomers when they retire, display the independence, self-sufficiency, and self-confidence they attained in their childhood. They are inclined to be suspicious and cynical, value a balance between family and work more than the previous generation, and are not particularly loyal to their employers since they do not expect their employers to be loyal to them. They can be motivated by an emphasis on the significance of their work, as well as by fun in the workplace, and managers must accept their skepticism for what it is: an honest observation of the employee-employer relationship. As Gen Y are the children of the Boomers, it is not surprising to find that they display values that conflict with those of their parents. They embody technical expertise, social networking, and the ability to be permanently “connected,” features that annoy their Boomer parents. At work they are eager to obtain immediate satisfaction, and demand exciting and relevant work, as well as reliable channels for promotion. Whereas the Boomers prefer to be allowed to do their work unhindered, Gen Y seeks attention and feedback. Despite their distinct profiles, Cennamo and Gardner (2008) found only few significant differences between the generations in respect to the relationships between work values, work satisfaction, organizational commitment, the intention to leave the organization, and the degree of fit between the values of the individual and the organization. The younger generations were found to ascribe more importance to status than the older one, perhaps because members of the older generation have already achieved status at work. Gen Y displayed more appreciation of freedom than Gen X and the Boomers, in line with their desire for greater autonomy and a family-work balance. If these values are not satisfied at work, they are inclined to look for another job. Higher congruency between the values of the individual and the rewards dispensed by the organization (such as salaries and benefits) was found among the Boomers than in Gen X and Gen Y. The authors suggest that this finding derives from the fact that the Boomers have more seniority and therefore enjoy higher status and salary and more significant benefits than the younger generations. In all three generations, low compatibility between individual and work values was associated with less work satisfaction and organizational commitment and a greater intention to leave. Thus, the literature reveals that each generation differs from the others in terms of the values and behaviors it has developed as a result of the historical context into which it was born. The implications of these differences in the workplace, however, have yet to be demonstrated with any consistency. The current paper seeks to shed further light on this issue by examining an additional aspect of the generational effect: the relationship between generational differences on the one hand, and two work attitudes and an organizational behavior on the other. Specifically, it examines whether generation plays a role in the relationships between job involvement, work satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior. Job involvement The connection between work and the individual's inner world is complex and profound, going well beyond the value of work as a source of income. Among other things, work constitutes part of the individual's self-image, and hence job involvement is an important means for satisfying deep-seated needs and enabling self-expression. Indeed, Lodahl and Kejner (1965) defined job involvement as the degree of the employee's personal involvement in his or her job on the psychological level, and distinguished between job involvement and occupational involvement. However, this characterization led to confusion between psychological identification and the employee's need to invest in his or her job in order to obtain self-esteem. Kanungo (1982) therefore redefined the concept, combining work and job, and maintaining that job involvement is the state of mental or psychological identification with a specific job which depends on both the importance of one's needs (intrinsic and extrinsic), and the perception of work as satisfying those needs. As the concept and resulting measure he developed are more inclusive and reliable than those developed by Lodahl and Kejner, they were employed in the current study. Researchers contend that job involvement is largely affected by the employee's personality traits and values, and less by organizational factors (Rabinowitz & Hall, 1977). Riketta and Van Dick (2009) suggest that job involvement contains two overlapping measures: psychological identification with the job, and the level at which work plays a central role in the individual's life and identity. In other words, job involvement is the degree to which the job situation is central to the person and his/her identity (Brown, 1996; Kanungo, 1982; Lodahl & Kejner, 1965). This bidimensionality is apparent in Kanungo's measurement tool, which reveals the two factors of (1) centrality of work in daily life, and (2) affective identification, as demonstrated by items such as: “The most important things that happen to me relate to my job” (centrality); “For me, work is only a small part of what I am” (affectivity). The current study therefore examined these two factors separately. Not only is job involvement a psychological, cognitive, and behavioral process that is affected by the employee's personality and values, but higher job involvement also works in the organization's favor. As well as bearing on the employee's psychological and physical health, research has shown that a high level of job involvement leads to positive attitudes of work satisfaction and high morale, which are then manifested in greater commitment and diligence. Work satisfaction Hoppock (1935) defines satisfaction as a combination of the psychological, circumstantial, physical, and environmental which causes people to say honestly, “I am satisfied with my job.” While employees may be satisfied with certain aspects of their work but not others, the assumption is that they can obtain a balance between satisfaction and dissatisfaction that produces an overall feeling of work satisfaction. According to Poling (1990), the best predictor of work satisfaction is the fit between the employee's values and the rewards provided by the organization. Defining work satisfaction as the collection of emotions and beliefs people have regarding their current job, George and Jones (2002) list four factors that can affect level of satisfaction: (1) Personality - the way a person consistently feels, thinks and behaves; (2) Values, specifically, intrinsic vs. extrinsic values, which reflect a person's beliefs regarding results and how they should behave at work; (3)Work conditions - i.e., tasks, the people with whom the employee associates, physical conditions, and work environment; and (4) Social influence – the influence of other individuals or groups (colleagues, family, cultural environment, etc.) on the employee's attitudes and behavior. Thus, like job involvement, work satisfaction is a psychological construct that is affected not only by organizational factors, but also by the personality, values, and beliefs of the individual employee. Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) First identified and defined in the 1980s (Smith, Organ, & Near, 1983), organizational citizenship behavior relates to the contribution of employees to the organization above and beyond the official demands of the job. In other words, it refers to behavior that is not recognized by the organization's formal reward system. Nevertheless, the organization requires this type of commitment in order to function effectively (Finkelstein & Penner, 2004). Indeed, studies indicate a relationship between OCB and employees' performance level (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Paine, & Bachrach, 2000). In their definition of OCB, Brief and Motowidlo (1986) note that it must fulfill the following characteristics: (a) the behavior is performed by organization members; (b) the behavior is directed toward individuals, groups, or organizations with whom the employee maintains a relationship within the framework of their job; (c) the behavior is performed with the intention of advancing the well-being of individuals or groups within the organization. Organ (1988) identifies five dimensions of OCB: (1) Altruism - helping another employee in carrying out tasks related to the organization; (2) Conscientiousness - devotion, showing respect for the organization and observing its rules; (3) Sportsmanship - refraining from making petty complaints; (4) Courtesy - consulting with work partners about actions that may affect their work; and (5) Civic virtue behaviors - involvement in the organization's political life, such as participation in meetings. In a study employing this five-dimensional model, Podsakoff et al. (2000) reported 0.70 reliability for each dimension. As noted above, OCB is not formally rewarded. It is therefore manifested in behaviors such as: not making use of all of one's vacation days and sick leave; helping colleagues to complete an assignment; refraining from complaints against the organization; maintaining positive work relationships with colleagues; demonstrating involvement in the life of the organization, and so on. Thus, citizenship behavior in the working world evidences support of the organization's goals and members through voluntary actions that promote the organization and go beyond the official job description. According to Cohen and Vigoda (2000), the benefits of OCB for the organization include improved productivity of teamwork and management, more effective use and allocation of resources, and enhancement of the organization's image which enables it to attract new high-quality employees. Consequently, the more members of the organization are willing to display OCB, the more effectively the organization will operate and the more successfully it will cope with its goals and challenges (Cohen & Vigoda,2000). The current study In view of the characteristics of each of the above study variables, we expected to find certain relationships between them. Moreover, given the distinct features of the three generations examined here, we predicted a generational effect on the interactions between job involvement, work satisfaction, and OCB, although we were unable to find any previous research investigating these relationships. Job involvement and work satisfaction. Since job involvement assumes that a job can satisfy an employee's needs, it follows, as Kanungo (1982) suggested, that greater involvement can be expected to be related to greater work satisfaction. Mowday, Porter and Steers (1982) contend that the more employees are involved in their job, the more their psychological needs are met. Similarly, Brown (1996) argues that employees who are highly involved in their job will identify with it more psychologically, and this in turn will reinforce their satisfaction. In other words, they believe that their personal goals and the organization's goals are compatible, and therefore they are satisfied with their work (Chay & Aryee, 1999) and tend not to consider changing jobs. Consequently, we expected to find a strong positive relationship between work satisfaction and the emotional factor of job involvement, that is, identification. In addition, we anticipated that generation would have a significant effect on the interaction between job involvement and work satisfaction. Job involvement and organizational citizenship behavior. Studies have shown that employees with a high degree of work satisfaction show a higher level of OCB. Moreover, given the positive effect of job involvement on work satisfaction, job involvement can be expected to enhance OCB as well (Podsakoff et al., 2000). Indeed, two empirical studies that examined the relationship between job involvement and OCB (Cohen, 1999; Diefendorff, Brown, Kamin, & Lord, 2000) found that job involvement could significantly predict the level of OCB displayed by employees. Chughtai (2008) argues that job involvement can predict not only normative role performance, but even activities beyond the demands of the job (i.e., OCB). Taking into account that OCB is affected by what people think and feel about the organization (Organ & Ryan, 1995), and that job involvement reflects a positive attitude toward the job, it seems clear why people with high job involvement will display more OCB than those with low job involvement. Consequently, we predicted a positive relationship between the identification factor of job involvement and all five dimensions of OCB. Moreover, we expected to find a generational effect on the relationship between job involvement and OCB, with the relationship between the two variables being stronger in the older generation as a result of its distinct work-related features. Personality. Although personality is not one of the study variables, the investigation deals with psychological behaviors. Furthermore, as seen above, personality may affect the degree of an individual's work satisfaction. We thus decided to use personality as a control variable so as to enable us to statistically control for any effect it may have on the interactions between the work-related variables in the study. Personality was conceived here as a bidimensional construct consisting of positive and negative affect (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Hypotheses: In view of the literature, we therefore hypothesized that positive relationships would be found between job involvement, job satisfaction, and OCB. Moreover, as these relationships have a psychological component, we expected to find that the emotional factor of job involvement, i.e., identification, would be more strongly associated with the other measures than the factor of centrality. The main objective of this study, however, was to examine whether generation has an effect on the relationships between the work-related variables. Given the qualitative differences between the personality structure of members of the three generations under study, we predicted that a generational effect would be found on the interactions between job involvement, work satisfaction and the five dimensions of OCB, even after controlling for the effect of individual personality depicted as positive and negative affectivity. Specifically, the following hypotheses were formulated: H1: A positive relationship will be found between the degree of job involvement and the degree of organizational citizenship behavior, so that greater job involvement on the factor of identification will lead to greater OCB on all five dimensions: altruism, courtesy, sportsmanship, conscientiousness, and civic virtue. H2: An interaction will be found between the degree of job involvement (both identification and centrality), generation, and all five dimensions of OCB. H3: A positive relationship will be found between the degree of job involvement and the degree of job satisfaction, so that greater job involvement on the factor of identification will lead to greater job satisfaction. H4: No interaction will be found between the two factors of job involvement and job satisfaction. Method Procedure and participants The study questionnaire was distributed over an Internet site, a method that has been found to be reliable and effective (Gosling, Vazire, Srivastava, & John, 2004). The website was available for a period of one month. For the first two weeks, the link to the site was provided to the employees at the workplace of one of the authors, and 86 responses were obtained. The link was then transferred to other individuals using the snowballing method. This resulted in a further 71 responses, for a total of 157. The final sample comprised 133 participants who completed the questionnaires in full (84.7%). The age of the participants ranged from 25 to 62 (M = 36.35, SD = 8.28); 86.9% were women; 72.2% were married, while 22.6% were single and 5.3% had a different family status. They had between 0 and 5 children (M = 1.38, SD = 1.25), and between one to 25 years of education (M = 16.15, SD = 2.41). Their seniority at work ranged from one month to 27 years (M = 5.03, SD = 4.47). In terms of place of employment, 58.5% of the participants worked for a bio-tech organization, 5.7% for a hightech company, 8.9% for a customer service organization, 2.4% worked in production, 8.1% were in the field of education, 4.1% worked in health services, 3.3% worked for consulting and guidance services, and 8.9% were employed by other types of organizations. Measures Organizational citizenship behavior. OCB was measured by a 20-item questionnaire (Niehoff & Moorman, 1993) tapping the five dimensions: altruism, courtesy, sportsmanship, conscientiousness, and civic virtue. Responses were indicated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Reliability values (Cronbach's alpha) for the five dimensions ranged from 0.59 to 0.79. A score was calculated for each participant on each of the dimensions by averaging the responses to the relevant items, with the direction of items formulated negatively reversed. Work satisfaction. Work satisfaction was measured by the 20-item Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) – short form. Responses were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally dissatisfied) to 6 (extremely satisfied). Preliminary factor analysis indicated that the relationship between items could best be described by means of a unidimensional structure. A satisfaction score was therefore calculated for each participant by averaging the responses to all items. Measure reliability (Cronbach's alpha) for the questionnaire was 0.93. Job involvement. Job involvement was measured by means of a 10-item questionnaire (Kanungo, 1982) to which participants responded using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (totally disagree). Eight items were reversed in view of earlier findings (Riketta & Van Dick, 2009) that job involvement consists of two factors: centrality and identification. In the current study, the reliability value (Cronbach's alpha) for centrality was 0.87, and for identification 0.61. Two factor scores were therefore calculated for each participant by averaging the responses to the relevant items. Personality. Personality was measured by means of the abridged version of the 12-item PANAS questionnaire, which assesses two dimensions: positive and negative affectivity (Watson, Clark & Tellegen, 1988). Responses were indicated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely not) to 5(absolutely). The reliability coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) in the current study was 0.88 and 0.89, for positive and negative affectivity, respectively. A score was therefore calculated for each participant on each dimension by averaging the responses to the relevant items. Results The relationship between generation and the other variables was examined by means of a one-way ANOVA. The hypotheses were then examined by a series of hierarchical multiple regressions. In order to assess the unique contribution of each of the variables, they were entered into the equation in three steps. The generation variable was represented in the analysis by two contrasts, one comparing Gen Y to the two previous generations, and the other comparing Gen X to the Boomers. The interaction variables were calculated by multiplying the job involvement score by each of these contrasts. Before calculating the interaction, the participating variables were centered by deducting their mean value from the value of each participant. This was done in order to neutralize the correlation between the interaction and each participating variable due to the effect of the mean, so as to facilitate interpretation of the coefficient obtained for each variable at the final stage of the regression analysis as its main effect. Univariate analysis: Distribution of variables Analysis using a box plot diagram did not indicate the existence of outstanding values, so that all observations were included in the statistical analysis. The distribution of the variables is presented in Table 1. Bivariate analysis: Correlations between variables Table 2 displays the Pearson correlations between the study variables. The correlations that emerged from the analysis largely uphold the study hypotheses. As expected, the majority of OCB dimensions correlated positively with job involvement, with stronger correlations emerging for the identification factor. Also as predicted, work satisfaction was found to be positively related to both the centrality and identification factors of job involvement, r = .22, p < .01; r = .50, p < .001, respectively. Furthermore, significant positive correlations were found between the OCB dimensions (with the single exception of conscientiousness) and work satisfaction. The findings also show that both personality dimensions were related to the majority of study variables, thus reinforcing our decision to control for personality when examining the study hypotheses. Multivariate analysis: Generational effect A MANOVA indicated no significant effect of generation on the rest of the study variables, (F (20,242) = .75, p > .05. The relationship between generation and the other variables was then examined by unidirectional variable analysis. The findings of the ANOVA are presented in Table 3. No association was found between generation and the other variables. This is in line with the hypothesis that generation together with job involvement would have an interactional effect on organizational citizenship behavior and work satisfaction, rather than showing a main effect of its own. Multivariate analysis: Examination of the study hypotheses A series of multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to examine the hypotheses predicting a positive effect of job involvement on the five dimensions of organizational citizenship behavior and on work satisfaction, as well as an interactional effect of job involvement and generation on these variables. In all the regressions, the independent variables were entered hierarchically: in Step 1 the two personality dimensions were entered as control variables; in Step 2 the three independent variables – the two factors of job involvement and generation - were entered, with Gen Y compared to Gen X and the Boomers since we believed that the latter generations were more similar to one another, while Gen Y was unique. Finally the interactions were entered in Step 3. The results of the analysis for altruism are presented in Table 4. As Table 4 shows, no significant effect of job involvement was found on the dimension of altruism in organizational citizenship behavior, β = 0.27, p > .05, β = 0.040, p > .05, for centrality and identification, respectively. Nor were significant interactions found on this dimension for the centrality of job involvement with the two generation contrasts (Gen Y vs. the other generations, β = .135, p > .05; Gen X vs. the Boomers, β = .116, p > .05), or for identification of job involvement with these two variables (Gen Y vs. the other generations, β = .119, p > .05; Gen X vs. the Boomers, β = .221, p > .05). Table 4 also shows that there is no statistical justification for controlling for personality in view of the lack of statistical significance of its two dimensions. Positive affectivity, which was significant in Step 1 of the regression, β = .187, p < .05, dissipated in the second and third steps after controlling for the effect of the main variables and their interactions. Table 5 presents the results of the regression for courtesy. As this Table indicates, no significant effect was found for job involvement on the dimension of courtesy in organizational citizenship behavior, β = .055, p > .05, β = .117, p > .05, for centrality and identification, respectively. However, a significant interactional effect was found between the identification factor of job involvement and the generation variable of Gen X vs. the Boomers, β = .270, p < .05, with the effect being more positive among Gen X than Boomer employees. This is shown in Figure 1, where the slope, representing the effect of job involvement on courtesy, is more positive among Gen X in comparison both with the main effect and with the slope produced by the Boomers. Thus, generation appears to mitigate the effect of job involvement on the courtesy dimension of OCB. The remaining interactions were not found to be significant. Table 5 also shows that there is no justification for controlling for personality in view of the lack of statistical significance of the effects of both its dimensions. Although positive affectivity was found to be significant in Step 1, β = .210, p < .05, it ceased to be significant in Steps 2 and 3 after controlling for the effects of the main variables and their interactions. Table 6 displays the results of the regression analysis for sportsmanship. The results show no significant effect of job involvement on the dimension of sportsmanship in organizational citizenship behavior, β = .002, p > .05, β = .122, p > .05, for centrality and identification, respectively. In addition, no significant interactions were found. However, the table shows that controlling statistically for personality was justified here, as both dimensions produced significant betas, β = .200, p < .05, β = .295, p < .05, for positive and negative affectivity, respectively. The results of the regression for conscientiousness appear in Table 7. The results show no significant effect was found for job involvement on the dimension of conscientiousness in organizational citizenship behavior, β = .022, p > .05, β = .016, p > .05, for centrality and identification, respectively. In addition, no significant interactions were found. The table also reveals no justification for controlling for personality in view of the lack of significance of the effects of both dimensions. Table 8 displays the results of the regression for civic virtue. As can be seen, a significant effect was found for the identification factor of job involvement on the dimension of civic virtue in organizational citizenship behavior, β = .242, p < .01). Thus, greater job involvement appears to lead to greater civic virtue. The effect of the centrality factor was not significant, β = .096, p > .05. However, a significant interactional effect was found between the centrality factor and the generational variable of Gen X vs. the Boomers, β = .290, p < .05), with the effect being more positive among Gen X than Boomer employees. This is shown in Figure 2, where the slope, representing the effect of job involvement on civic virtue, is more positive among Gen X in comparison both with the main effect and the slope produced by the Boomers. Thus, generation appears to mitigate the effect of the centrality factor of job involvement on civic virtue. The remaining interactions were not significant. Figure 2 also indicates statistical justification for controlling for personality, as a significant effect emerged for positive affectivity, β = .297, p < .001. The results of the regression for work satisfaction are presented in Table 9. As this Table reveals, a significant effect was found for the identification factor of job involvement on the degree of work satisfaction, β = .410, p < .001, with greater job involvement leading to greater work satisfaction. The effect of centrality was not significant, β = .028, p > .05, and no significant interactional effects were found. Furthermore, Table 9 indicates justification for controlling for personality, as a significant effect emerged for negative affectivity, β = .277, p < .001. Summary of the results • Support was found for Hypothesis 1, predicting a positive effect of job involvement on the various dimensions of OCB, only in respect to the dimension of civic virtue. As predicted, this effect was found for the job involvement factor of identification. Thus, greater involvement in one's job in terms of identification is associated with more moral behavior. • Interactions were found between the identification factor of job involvement and generation on the dimension of courtesy, and between the centrality factor of job involvement and generation on the dimension of civic virtue. In both cases, the effect of job involvement was more positive among Gen X employees than among Boomers. These findings lend partial support to Hypothesis 2. • A significant positive effect on the degree of job satisfaction emerged for the identification factor of job involvement, thereby providing support for Hypothesis 3. • In line with Hypothesis 4, no interactional effect was found for either factor of job involvement on job satisfaction. Discussion In line with previous studies, greater job involvement was found here to be related to higher work satisfaction and OCB (Podsakoff et al., 2000). The present study, however, adds to this understanding by showing that the relationship exists mainly on the level of affect, that is, on the factor of identification rather than centrality of job involvement. This was found to be true in respect to both work satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior. In their meta-analysis, Riketta and Van Dick (2009) also report a correlation of 0.54 between work satisfaction and identification, as compared with 0.35 for work satisfaction and involvement. The results may reflect a feature of the contemporary work world, where extremely demanding jobs (such as in high-tech companies) require employees to work extra hours, making work central to their lives, but not necessarily by choice. This may explain why satisfaction and OCB are more related to the factor of identification, which represents a choice and relates to a psychological and emotional relationship, i.e., satisfaction of the needs of the employee (in line with the Social Exchange Theory), and not merely to the amount of time and effort they invest in their jobs. While it is this distinction that has led to the twodimensional conceptualization of job involvement, Yoshimura (1996) suggests redefining the concept as a three-dimensional structure consisting of an emotional association (interest and liking), a conscious psychological state (self-esteem and active participation), and an intentional behavioral dimension (doing more than would be expected from the position). In only partial support of our hypothesis, a positive relationship was found between the identification factor of job involvement and just one of the five dimensions of OCB, civic virtue (behavior directed toward the organization). Civic virtue reflects undertaking personal responsibility for participation in the organization's political life, such as attending meetings, making suggestions for more efficient use of resources, etc. Employees who strongly identify with the organization can be expected to make more of an effort to improve productivity and effectiveness (Yen & Neihoff, 2004). However, when examining the effect of the interactions between job involvement and generation on OCB, an interaction was found between the centrality factor and generation, whereby greater centrality of work had a more positive effect on the civic virtue of Gen X employees than Boomers. It is difficult to explain this finding in view of the generational profile. We expected Baby Boomers, who are more loyal to the organization, workaholics, appreciate hard work, and work extra hours, to invest more in their jobs than Gen X employees, who are more loyal to themselves than to the workplace, value the balance between family and work, and seek pleasure at work. It is possible that the Boomer generation is “tired” and therefore less involved in OCB, or perhaps they are now “resting on their laurels” having already gained recognition of their status at work. On the other hand, Gen X are at the height of their integration into the workplace, and have spent sufficient years in the organization (or profession) to feel comfortable engaging in civic virtue behavior. In other words, they are familiar enough with the organizational processes to be able to suggest ways of solving problems and enhancing effectiveness. Moreover, they are still seeking promotion, and therefore tend to invest more time and effort (centrality) in the political life of the organization. Another explanation is suggested by the study by Cohen and Avrahami (2006), who found a strong positive connection between individualism and OCB on the dimension of civic virtue. As noted above, Gen X displays more salient characteristics of individualism than collectivism, such as not being dependent on others and relying on themselves (Whitney et al., 2009). An interaction was also found between the identification factor of job involvement and generation on the OCB dimension of courtesy, whereby Gen X employees who identify more with the organization evidenced more courtesy than Baby Boomers. Courtesy relates to consulting with others at work about activities that may affect their work (behavior directed at the individual), and includes both informal and formal activities, such as announcing one's intentions in advance, transferring information, and so on (Organ, 1988). Although the dimension of courtesy yielded a low reliability in this study, the fact that a significant interaction was found reinforces its existence de facto. This finding may be explained in terms of Gen X's position in the workplace. Members of this generation currently occupy an intermediate status. While most do not yet belong to senior management, they serve in middle management jobs such as team leaders, direct managers, etc., and therefore both consult with their superiors and are in direct contact with their subordinates. At present, Gen X is the dominant generation in the work market. It is therefore encouraging to find that it is also the generation displaying the strongest and most positive effect on job involvement and OCB. No significant interactions were found here for either Gen Y or the Boomers on these variables. The findings thus raise doubt as to whether it is really necessary to invest a great deal of effort in attempts to bridge the generation gap in the workplace. In view of our findings, it is possible that the gap has, in fact, already been bridged. Certain limitations of the study should be noted. First, it was conducted among employees from several sectors. Additional interactions might have been found had the sample been drawn from a single sector where all the participants shared the same organizational experiences and culture. Secondly, the OCB instrument employed here was a self-report questionnaire. It might be preferable to confirm the responses by means of a more objective source, such as the employee's direct manager. Finally, we used a cross-sectional design to examine generational differences. A time-lag investigation examining people of the same age cohort at different points in time, as proposed by Twenge (2010), might produce additional insights. It goes without saying that different generations uphold different values. The question we sought to investigate here was whether these differences affect processes, performance, and outcomes in the workplace. The findings indicate that generation mitigates the effect of job involvement on OCB on two dimensions out of five (courtesy and civic virtue), with the effect of this interaction being most positive among Gen X employees. As the objective of all organizations is to enhance the degree of OCB in order to help render performance more effective, there is room to examine the reasons for the fact that a significant positive effect was not found for Boomers or Gen Y employees. Moreover, the current findings show that job satisfaction does not depend on generation or age. However, as the results are not unequivocal, we would recommend examining additional connections that may be affected by generation. To conclude, we are inclined to agree with Ecclesiastes: “Generations come and generations go, but the earth remains forever.” Perhaps the best course for an organization to adopt is to recruit as diverse a workforce as possible in order to create a balance between the different influences of each generation, and indeed, between different individuals as human beings. 1The names of this paper's authors are listed in an alphabetical order. References 1. Brief, A. P. & Motowidlo, S. J. (1986). Pro-social organizational behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 11, 710-725. [ Links ] 2. Brown, S. P. (1996). A meta-analysis and review of organizational research on job involvement. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 235-255. [ Links ] 3. Cennamo, L. & Gardner, D. (2008). Generational differences in work values, outcomes and person-organization values fit. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23, 891. [ Links ] 4. Chay, Y. W. & Aryee, S. (1999). Potential moderating influence of career growth opportunities on careerist orientation and work attitudes: Evidence of the protean career era in Singapore. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 613-623. [ Links ] 5. Chughtai, A. A. (2008). Impact of job involvement on in-role job performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 9, 169-184. [ Links ] 6. Cohen, A. (1999). The relationship between commitment forms and work outcomes in Jewish and Arab culture. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 371-391. [ Links ] 7. Cohen, A. & Avrahami, A. (2006). The relationship between individualism, collectivism, the perception of justice, demographic characteristics and organizational citizenship behavior. The Service Industries Journal, 26, 889-901. [ Links ] 8. Cohen, A. & Vigoda, E. (2000). Do good citizens make good organizational citizens? An empirical examination of the elationship between general citizenship and organizational citizenship behavior in Israel. Administration and Society, 32, 596-625. [ Links ] 9. Crampton, S. M. & Hodge, J. W. (2007). Generations in the workplace: Understanding age diversity. The Business Review, 9, 16-23. [ Links ] 10. Diefendorff, J. M., Brown, D. J., Kamin, A. M., & Lord, R. G. (2002). Examining the roles of job involvement and work centrality in predicting organizational citizenship behaviors and job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 93-108. [ Links ] 11. Egri, C. & Ralston, D. (2004). Generation cohorts and personal values: A comparison of China and the US. Organization Science, 15, 210-220. [ Links ] 12. Eisner, S. P. (2005). Managing generation Y. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 70, 4-8. [ Links ] 13. Finkelstein, M. A. & Penner. L. A. (2004). Predicting organizational citizenship behavior: Interacting the functional and role identity approaches. Social Behavior and Personality, 32, 383-389. [ Links ] 14. George, J. M. & Jones, G. R. (2002). Understanding and managing organization behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ] 15. Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about Internet questionnaires. American Psychologist, 59, 93-104. [ Links ] 16. Hoppock, R. (1935). Job satisfaction. New York: Harper and Brothers. [ Links ] 17. Johnson, J. A. & Lopes, J. (2008). The intergenerational workforce revisited. Organizational Development Journal, 26, 31-37. [ Links ] 18. Kanungo, R. N. (1982). Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 341-49. [ Links ] 19. Karp, H., Fuller, C., & Sirias, D. (2001). Bridging the boomer gap: Creating authentic teams for high performance at work, Palo Alto: Daris Black Publishing. [ Links ] 20. Kupperschmidt, B. R. (2000). Multigenerational employees: Strategies for effective management. The Health Care Manager, 19, 65-76. [ Links ] 21. Lancaster, L. C. & Stillman, D. (2002).When generations collide: Traditionalists, baby boomers, generation Xers, millennials: Who they are, why they clash, how to solve the generational puzzle at work, New York: Harper Collins. [ Links ] 22. Leyden, P., Teixeira, R., & Greenberg, E. (2007). The progressive politics of the millennial generation. New Politics Institute. http://www.newpolitics.net/node/360?full_report=1. Retrieved May 8, 2010. [ Links ] 23. Lodahl, T. & Kejner, M. (1965). The definition and measurement of job involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 49, 24-33. [ Links ] 24. Mannheim, K. (1953). Essays on sociology and social psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ] 25. Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), short form (1977). [ Links ] 26. Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-organization linkage. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [ Links ] 27. Neil, S. (2010). Leveraging generational work styles to meet business objectives. Information Management Journal, 44, 28-33. [ Links ] 28. Niehoff, B. F. & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior, Academy of Management Journal, 36, 527-556. [ Links ] 29. Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. [ Links ] 30. Organ, D. W. & Ryan, K. (1995). A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48, 775-800. [ Links ] 31. Patota, N., Schwartz, D., & Schwartz, T. (2007). Leveraging generational differences for productivity gains. Journal of American Academy of Business, 11, 1-11. [ Links ] 32. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., & Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26, 513-563. [ Links ] 33. Poling, R. L. (1990). Factors associated with job satisfaction of faculty members at a land-grant university. Doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University. [ Links ] 34. Rabinowitz, S. & Hall, D. T. (1977). Organizational research on job involvement. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 265-88. [ Links ] 35. Reisenwitz, T. H. (2009). Differences in generation X and generation Y: Implications for the organization and marketers. The Marketing Management Journal, 19, 91-103. [ Links ] 36. Riketta, M. & Van Dick, R. (2009). Commitment's place in the literature. In: H. J. Klein, T. E. Becker, & J. P. Meyer (Eds.), Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions (pp. 69-95). New York: Routledge. [ Links ] 37. Smith, C. A., Organ, D. W., & Near, J. P. (1983). Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents, Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 653-663. [ Links ] 38. Streeter, B. (2007). Welcome to the new workplace. ABA Banking Journal, 99, 7-13. [ Links ] 39. Twenge, J. M.(2010). A review of the empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 201-210. [ Links ] 40. Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of Positive and Negative Affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070. [ Links ] 41. Weil, N. (2008). Welcome to the generation wars: As boomer bosses relinquish the reins of leadership to generation X both are worrying about generation Y. CIO, 21. [ Links ] 42. Whitney, J. G., Greenwood, R. A., & Murphy, E. F. (2009). Generational differences in the workplace: Personal values, behaviors, and popular beliefs. Journal of Diversity Management. 4, 1-8. [ Links ] 43. Yen, H. & Neihoff, B. (2004). Organizational citizenship behavior and organizational effectiveness: Finding relationship in Taiwanese banks. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 1617-1637. [ Links ] 44. Yoshimura, A. (1996). A review and proposal of job involvement. Keio Business Review, 33, 175-184. [ Links ]

Aharon Tziner

Schools of Behavioral Studies and Business Administration

Netanya Academic College

Jerusalem, Israel

E-mail address: atziner@netanya.ac.il

Manuscript Received: 20/05/2011

Revision Received: 22/07/2011

Accepted: 22/07/2011