Labor conditions in Spain decayed after 2008 international economic crisis (Dávila-Quintana & Lopez-Valcarcel, 2009); job availability between 2008 and 2012 dipped by 2.9 million and youth unemployment rose from 18.1% to 46.2% (Eurostat, 2015d). With limited opportunities in the labor market, will personal resources continue to predict perceived employability to the same extent? Although we know that human capital and labor market factors predict perceived employability (Berntson et al., 2006; Fugate et al., 2004; Hillage & Pollard, 1999; Van Der Heijde & Van Der Heijden, 2006), how changing labor market conditions impact the relationship between human capital and perceived employability remains unclear.

The Spanish Labor Context

Recent events in Spain offer an opportunity to understand the impact of labor market conditions on the relationship between human capital and perceived employability in young people. In the years between 1997 and 2007, the construction and property industry in Spain flourished; Spain experienced intense economic growth and had achieved a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of 105% of the EUaverage (Eurostat, 2016). However, despite the growing and well-performing economy, the global financial crisis in the late 2008 indirectly led to the crashing of the construction bubble, and many people became unemployed. By 2009, a year into recession, unemployment grew from 8.2% to 17.9% (Eurostat, 2015c), youth unemployment inflated by 25 percentage points and long-term unemployment rose from 1.7% to 4.3% (Eurostat, 2015b). Various scholars posit that the existing deep-seated structural issues, such as rigid employee protection legislation (EPL), extreme market duality, and high market volatility in the Spanish labor market, contributed indirectly to the exacerbation of the unemployment situation during the crisis (Dávila-Quintana & Lopez-Valcarcel, 2009; García-Montalvo, 2012; Rocha Sánchez, 2012; Sala & Silva, 2009). For instance, factors like EPL and wage rigidity which protected permanent employees, facilitated the exercise of external flexibility (i.e., the dismissal of temporary workers) in response to market fluctuations and shocks rather than wage or work hours adjustments, which further contributed to market duality and volatility during recession (Sala & Silva, 2009). This is congruent with observations indicating that the majority of job loss during the initial stage of recession were concentrated on temporary workers (Corujo, 2013). However, as recession continued into 2010, permanent workers were also affected, as job creation and recovery prognosis were low (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions [Eurofound, 2013]). By 2012, both temporary and permanent workers were affected in a similar manner (Corujo, 2013).

Study Objective

This study aimed to understand if personal resources predict perceived employability in young people differently during normal and harsh labor market conditions by using two cross-sectional sample collected in the year 2008 (normal condition) and 2011 (harsh condition). For the purpose of investigating the differential roles of personal resources in predicting perceived employability, year 2008 is labelled as normal condition as it marks the onset of recession in Spain although global economic recession started in about late 2007. Thus, the fall of Lehman Brothers (15thSeptember 2008) could be considered as the starting point of the financial and economic crisis, and its effects started to be perceived in Spain at last three-months period in 2008, as economic press reflected. Spanish GDPincreased by 1.1% along 2008, but in the last three-month period of 2008 GPDdecreased a 0.8%. Year 2011 is labelled as harsh condition as Spanish economy was in the midst of recession with distinctly high unemployment rates and low job vacancies compared to 2008 (21.4% in 2011 vs. 11.3% in 2008;Eurostat, 2015c). This study focuses its attention on young people because they are more vulnerable to labor market fluctuations (Gangl, 2002) as temporary contracts (or fixed-term contracts), due to its low entry requirements, are commonly used by young Spaniards to facilitate entry into the labor market. However, the strict EPLand external flexibility also facilitated their exit when labor market conditions or economic situation became harsh (European Commission, 2010). In addition, studies indicate that it is tougher for young people to obtain permanent contracts during harsh labor conditions (Eurofound, 2013). Thus, during harsh times young people are in a more precarious situation of falling into long term unemployment, which can be detrimental to their future productive capabilities (Gregg & Tominey, 2005; Korpi et al., 2003). Studies show that long term unemployment in one's early career can have a significant effect on the life course and future employment capabilities (Gregg & Tominey, 2005; Korpi et al., 2003). Thus, understanding the relationship between personal resources and perceived employability in a harsh labor condition can be valuable for career counselling and vocational psychology in supporting young people during tough times. In other words, understanding if personal resources predict perceived employability differently when labor conditions change can plausibly assist career practices to better support young people in maintaining and enhancing their employability perceptions during tough times and in preparation for economic recovery where competition will be intense. In general, maintaining and enhancing one's employability perception is important because it can lower the likelihood of being psychologically harmed by unemployment (Fugate et al., 2004; McArdle et al., 2007), protect one's self concept and self-esteem (McArdle et al., 2007) during unemployment, strengthen sense of security and independence during unemployment (Daniels et al., 1998; Rothwell & Arnold, 2007), and support individuals to cope during job search (Chen & Lim, 2012). In addition to coping during unemployment, scholars have also found perceived employability to positively relate to health, well-being, and life satisfaction (Berntson & Marklund, 2007; De Cuyper et al., 2008). Thus, the main aim of our study is to analyze if during poor labor market conditions (high unemployment rates and lack of job offers) variables related with youngsters' perceived employability remain the same and if their predictive capability is reinforced, as compared with more favorable labor market condition.

Perceived Employability and Personal Resources

Perceived employability is the subjective perception of one's possibilities of obtaining and maintaining employment (Berntson & Marklund, 2007). It encompasses self-appraisal of one's capacity (i.e., personal factors such as competence, dispositions, and human capital) to obtain a job successfully in the current labor market (Berntson et al., 2006; Forrier & Sels, 2003; Rothwell & Arnold, 2007; Vanhercke et al., 2016). According to Vanhercke et al., (2014), perceived employability have four characteristics: i) subjective evaluation, ii) employment possibilities, iii) universality, and iv) the labor market. Vanhercke et al. (2014) refers to subjective evaluation as the psychological interpretation of one's employability, which will differ among individuals even if they are in the same objective event and have the same demographics. This is because individuals may include factors such as their professional networks (i.e., social capital) or their motivation to participate in employability-enhancing activities (Vanhercke et al., 2014; Wittekind et al., 2009) when evaluating their employability. Employment possibilities, according to Vanhercke et al. (2014), refers to the evaluation of personal factors, structural factors, and their interactions. Personal factors can include competences (e.g., occupational expertise, corporate sense; Van Der Heijde & Van Der Heijden, 2006), dispositions (e.g., openness to changes at work, work identity, work and career resilience; Fugate & Kinicki, 2008), and human capital (e.g., knowledge, skills, attitudes, and others; Fugate et al., 2004). Structural factors, according to Vanhercke et al. (2014), can include the level of the job (Forrier & Sels, 2003; Ng et al, 2005), organization, and job availability (Forrier & Sels, 2003; Rothwell & Arnold, 2007). We used the term universality to epitomize what Vanhercke et al. (2014) narrate as "obtaining and maintaining" employment. It essentially theorizes perceived employability as applicable to both the employed (hence the term 'maintaining') and unemployed or job entrants (hence the term 'obtaining'), and individuals making career transitions. This is because regardless of one's employment status, individuals can self-evaluate their employability based on market demands (Rothwell & Arnold, 2007). By means of the term 'labor market', we epitomize what Vanhercke et al. (2014) narrate as 'employment' possibilities with either the current employer (i.e., internal labor market) or with another employer (i.e., external labor market), which subsequently relates to perceived internal employability and perceived external employability respectively (Rothwell & Arnold, 2007).

Career-enhancing strategies. As elaborated by Vanhercke et al. (2014), perceived employability may involve subjective evaluation of one's motivation to participate in employability-enhancing activities. In this paper, employability-enhancing activities is represented by the personal resource variable of career-enhancing strategies, which is defined as the ways by which individuals are empowered to take responsibility for their development and performance (Feij et al., 1995). In a way, career-enhancing strategies represents one's propensity to invest in their human capital, and it can amplify one's chances and employment possibilities. This is because individuals high on human capital tend to have the necessary or required knowledge, skills, attitudes, and competencies (KSAO) that enable them to work productively and fulfill performance expectations (Becker, 1975; Burt, 1997). Therefore, based on the human capital theory (Becker, 1975), employers often want to attract, select, and retain such individuals as they contribute to organizational adaptability and objectives (Becker, 1975; Feij et al., 1995; Tharenou, 1997). In fact, to remain attractive in the labor market, there is a need for continuous development beyond academic, vocational, and technical skills (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2010; Coetzee & Roythorne-Jacobs, 2006; Fugate, 2006). According to Baker and Aldrich (1996) and Feldman (1996), higher involvement in developing one's career enhances both employability and employability perception. In addition, career-enhancing strategies consist of a behavioral variable contributing to one of the components of employability as a psychosocial construct (Fugate et al., 2004), as is career adaptability. Previous research used different variables to measure adaptability, with general self-efficacy being the most common (for instance, González-Romá et al., 2018), but there is no consensus about how to operationalize this construct. In the current study, we consider career-enhancing strategies as one of the factors that contributes to career adaptability. Therefore, we believe that young people who invested more in career-enhancing strategies will perceive themselves as more employable. Therefore, regardless of the market condition, we hypothesize that career-enhancing strategies positively predict perceived employability (H1a).

Personal initiative. When assessing one's employment possibilities, individuals evaluate various personal factors such as competences, dispositions, and human capital (Fugate & Kinicki, 2008; Fugate et al., 2004; Van Der Heijde & Van Der Heijden, 2006; Vanhercke et al., 2014). Among a myriad of personal factors, such as career self-efficacy, career identity, etc., we focus our attention on personal initiative. Personal initiative in general refers to a collection of behaviors (such as self-starting, proactive, and persisting) individuals enact to overcome challenges and to achieve their goals (Frese & Fay, 2001; Frese et al., 1997). Personal initiative at work refers to goal-directed proactive behavior aimed at improving work methods and procedures, and enhancing one's personal development for managing future work demands (Frese & Fay, 2001; Sonnentag, 2003). According to Frese et al. (1996), there are five aspects of personal initiative at work: i) it is consistent with the organization's mission, ii) it has a long term focus, iii) it is goal directed and action oriented, iv) it is persisting when meeting with challenges and setbacks, and v) it is self-starting and proactive.

We focus on personal initiative because it is an employability asset (Hillage & Pollard, 1999), and an active performance concept for work in the 21stcentury (Den Hartog & Belschak, 2007; Frese & Fay, 2001; Ohly et al., 2006). For instance, personal initiative has been found to relate to organizational citizenship behavior (Munene, 1995; Organ, 1990), and it indirectly contributes to organizational effectiveness (Organ, 1988). In the same vein, proactivity at work has been found to enhance work performance (Crant, 1995) and career outcomes (Seibert et al., 1999), and proactive behaviors such innovation and career initiative have been shown to enhance career success and career satisfaction (Seibert et al., 2001). In addition, individuals with initiative tends to be more active in managing their careers (Fugate et al., 2004), and this is aligned with the concept of protean career, which refers to self-directed career management where one's internal values drive career success (Hall, 1996). In fact, scholars such as Hall and Chandler (2005) emphasized that it is important for individuals the need to take personal initiative to develop themselves and their career especially in the contemporary career context.

Personal initiative has been found to positively relate with some job search variables as gaining new employment (Warr & Fay, 2001), and being evaluated more positively in job interviews (Frese et al., 1997), but few studies analyzed its relationship with employability. In the same line of Gamboa et al. (2009), we also expect, regardless of labor market conditions, personal initiative to positively predict perceived employability (H1b).

Career passivity. While individuals with initiative tend to focus on ways to achieve their long-term goals, and tend to go the extra mile to resolve work related challenges, passive individuals, on the other hand, tend to do as they were told and react to environmental demands rather than being proactive (Frese & Fay, 2001). However, career passivity is not quite the opposite of personal initiative; instead, career passivity is defined as the lack of active attempts to influence one's career directions (Frese et al., 1997). Career passivity is included in the study as we conjure that young people entering the Spanish labor market may be somewhat career passive as a large percentage of them (> 60%) relied on temporary contracts to facilitate entry into the labor market (Eurofound, 2013; García-Montalvo, 2012; Rocha Sánchez, 2012). These young entrants face the risk of getting trapped in precarious work arrangements and move from one temporary contracts to another when conversion to permanent positions or possibilities for upward mobility is lacking (European Commission, 2010; Gangl, 2003; OECD, 2013). Because career advancement prognosis are uncertain and young people may need to obtain another job when contract ends, being less concerned about their career plans and paths may support them to cope during job transition. In addition, as they are less concerned about their career paths when they first enter the labor market, they may be more flexible and less demanding concerning job offers. In other words, youngsters could show bigger adaptability to job offers when they do not make very specific plans and are open to accept the offerings and opportunities the labor market give them. Hence, we postulate that some career passivity may give them a heightened sense of perceived employability. In other words, we propose that, regardless of labor market conditions, career passivity positively predicts perceived employability (H1c).

Personal Resources and Harsh Labor Conditions

During economic recessions, the tightening of credit market and decline in spending and overall consumption in the economy lead to a decrease in demands for goods and services. This situation, in turn induces job destruction at organizational level (e.g., going out of business) and industry level (e.g., Spanish construction industry), leading to a consequential surge in cyclical unemployment (Chen et al., 2011). It also forces business to be more critical with their resources and spending. To cope with recession, organizations may take on defensive measures such as reducing employee benefits and training expenditure, laying off employees to maintain a lean workforce or to optimize operational efficiency (Gulati et al., 2010). In such scenario, we posit that employers will endeavor to seek, attract, and retain individuals with high human capital in order to maintain organizational flexibility and competitiveness while keeping expenditure (such as employee training) low during recession. This supposition is based on the human capital (Becker, 1975) theory and the resource-based view of the organization (Barney, 1991), which points towards human capital as resources and assets individuals bring to the organization. These individual resources support individuals to carry out their work roles and tasks effectively, which in turn influence work performance and organizational outcomes (De Cuyper et al., 2011). In view of this and together with Brewe's (2013) contention that employers prefer employees who continuously develop themselves, we hypothesize that during harsh conditions where competition to obtain a job is high (e.g., due to high unemployment and low job availability), young people who are investing more on career-enhancing strategies will have a higher employability perception. In another words, career-enhancing strategies will gain predictive strength during harsh labor condition when compared with normal labor market conditions (H2a).

We also expect the role of personal initiative to be more salient in predicting perceived employability during harsh condition. This is because personal initiative is positively related to protean career mindset and education initiatives (such as continuing education and enrolling in self-development course etc.) (Warr & Fay, 2001), which can enlarge one's job options and opportunities, leading to a higher employability perception. In a way, similar to career-enhancing strategies, personal initiative can signal one's propensity for personal development and may support individuals in their job search and in adapting to new work demands (Warr & Fay, 2001), both during and after recession. In addition, individuals with initiative tend to be more proactive and are more willing to go beyond work roles to resolve work related challenges (Frese & Fay, 2001). As such, personal initiative has been considered as an employee's characteristic that contributes to organizational effectiveness (Motowidlo & Van Scotter, 1994), which employers seek in job applicants (Shafie & Nayan, 2010; Youth Employment Network, 2009; see also Brewe, 2003). Thus in the same vein as Frese and Fay (2001), who postulated an increase in the demand for individuals with personal initiative in competitive job markets, we hypothesize that personal initiative will gain predictive strength during harsh labor conditions when compared with normal labor market conditions (H2b).

Lastly, we postulate that career passivity will gain relevance in predicting perceived employability in harsh labor market conditions. This is because, by the year 2011, young people on part-time contract increased from 22.9% in 2008 to 32.6% and young people on temporary contracts (or fixed-term contract) rose from 59.9% to 61.2% (Eurostat, 2015a). As prospects for a career are limited during harsh conditions, being less preoccupied and less directive with planning one's career directions and being more open and flexible may increase the sense of employability as it may widen job options and increase and perceive chances of gaining employment. This notion arises because studies have found that individuals who utilize a combination of engagement (such as career-enhancing strategies) and disengagement strategies (such as career passivity) tend to cope better with persistent futile job searches and prolonged unemployment (Lin & Leung, 2010; Searle et al., 2014). In the same line of reasoning, passivity or career disengagement had been considered as an adaptive way of coping with unemployment, reducing detrimental effects of occupational uncertainty and preventing mental health when labor market conditions are negative (Tomasik et al., 2010; Korner et al., 2012). In similar terms, external attribution in case of failure to maintain a job in uncertain conditions could protect self-esteem and self-image as the specific context allows attributing their situation to labor market factors (Buffel et al., 2015; Dudal & Bracke, 2019), thus facilitating to become more passive in front of harsh labor market conditions. Thus, we hypothesize that career passivity will also gain predictive strength in harsh conditions when compared with more favorable labor market conditions (H2c).

Method

Participants and Procedure

The two cross-sectional data waves for this study were obtained from the Spanish Observatory of Young People's Transition into the Labor Market [Observatorio de Inserción Laboral de Los Jóvenes] (Fundación Bancaja e IVIE, 2012). Data were collected by the observatory in 2008 and 2011, from May through June. Respondents were young people aged between 16 to 30 years who were entering the labor market in the previous five years at the time of the survey, i.e., seeking or having found their first job between 2003 and 2008 and between 2006 and 2011, respectively. The sampling distribution was formulated according to the percentage of young people in each region (except Ceuta, Melilla, Canary Islands, and Balearic Island) in the national total (census by the National Statistics Institute [Instituto Nacional de Estadística]). Overall, respondents were from 34 cities and small towns from 17 Spanish provinces, and were considered representative of both urban and non-urban areas in Spain.

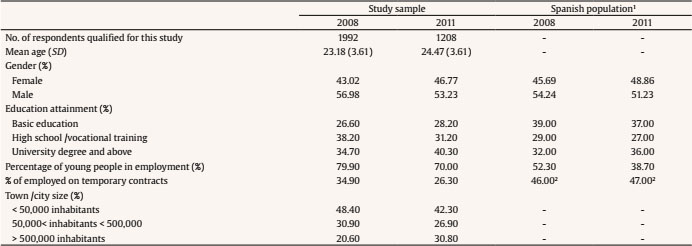

Table 1. Sample Demographics together with Some Comparative Information of the Spanish Population

Note. 1(Eurostat, 2018b) unless otherwise indicated; 2(Eurostat, 2018a).

Through a telephone call, the first contact with respondents was established. In the call, interviewers introduced the characteristics and importance of the survey. Following a verbal consent, a face-to-face interview was arranged at either a respondent's home or a mutually agreed location. Respondents completed the questionnaire in the presence of an interviewer.

Sample Description

Sample size was n= 3,000 for 2008 survey and n= 2,000 for 2011 survey, respectively. Study questions for this study were located in a section addressed for people currently working or who worked previously. As cases with missing data were removed, 66.4% (N2008= 1,992) of respondents from the 2008 survey and 60.4% (N2011= 1,208) from the 2011 survey remained and 'qualified' to participate in this study. Briefly, mean age of participants from the 2008 sample was 23.18 (SD= 3.61), 43.0% were male, and 79.9% were employed at the time of the survey. The mean age of participants from the 2011 sample was 24.47 (SD= 3.61), 46.8% were male, and 70.0% were employed at the time of the survey. Table 1presents demographics of the two samples, together with some demographics of the Spanish population to provide a picture of comparability to the Spanish population.

Measures

Participants answered all items based on a 5-point Likert scale with a response choice of (1) rarely to (5) often, unless otherwise noted.

Perceived employability (PE). Perceptions about one's possibilities in the current labor market were assessed using three items from the Employment Outlook scale in the Career Exploration Survey (Stumpf et al., 1983). Items were: "In the current labor market, it seems possible to find work for which Iam prepared or have experience", "In the current labor market, it is possible to find a job in a firm of my choice", and "In the present labor market situation, Icould find a job with the time dedication Iprefer". Scale reliability Chronbach's alphas (a) for 2008 and 2011 were .79 and .72 respectively.

Career-enhancing strategies (CES). Strategies to enhance one's career were assessed using three items from the Proactive Career Behavior Questionnaire (Claes & Ruiz-Quintanilla, 1998). Items included were: "Itry to talk to a senior about what Icould do to prepare myself", "Ihave been reflecting on what Icould reach in my work in the next few years", and "Idevelop skills that Imay need for future jobs". The scale had an alpha of .63 and .67 for 2008 and 2011 sample.

Personal initiative (PI). PIwas measured using three items from the Self-reported Initiative scale (Frese et al., 1997). Scale items were: "Whenever there is a chance to get actively involved, Itake it", "Itake initiative immediately even when others do not", and "Iusually do more than what Iwas asked to do". Scale reliability Cronbach's alphas for 2008 and 2011 were .75 and .82 respectively.

Career passivity (CP). Passiveness in career planning was measured by three items from the passivity scale (Frese et al., 1997). Scale items were: "It is still early to make plans for my future career", "Regarding work, it is best to wait and see what happens", and "Iplan when Iclearly know what is going to happen". Scale reliability for 2008 and 2011 was .82 and .81 respectively.

Control variables.We measured demographics such as age, gender (1 = male, 2 = female), education level (0 = no education, 1 = primary, 2 = secondary, 3 = high school or vocational training, 4 = university or higher vocational, and 5 = postgraduate) and town/population size (1 = less than 50,000 inhabitants, 2 = from 50,000 to 500,000 inhabitants, 3 = more than 500,000 inhabitants). In addition, employment status (0 = unemployed, 1 = employed), type of contract (0 = other forms of employment or unemployed, 1 = permanent, 2 = temporary), and total family income as an indicator of social-economic-status (SES; monthly income: 1 = less than €1,000, 2 = from €1,000 to €1,800, 3 = from €1,800 to €2,600, 4 = from 2,600 to €3,400, and 5 = more than €3,400) were included. We considered employment type as a control because temporary contracts are commonly utilized by young Spaniards to facilitate entry into the labor market (Eurofound, 2013; García-Montalvo, 2012; Rocha Sánchez, 2012), hence, it may have some influence on employability perception. City/town size was considered as a control because more populated regions tend to have more varied labor market than sparsely populated regions (Berntson et al., 2006), which may influence job availability and subsequently employability perception.

Analyses

All the analyses involving latent variable modelling were carried out in AMOS23.0 (Arbuckle, 2014). Given that χ2statistics is sensitive to large sample size, we utilized multiple goodness-of-fit indices to assess model fit, namely the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). For CFIand TLI, values above .90 are recommended as indications of an acceptable fit, while values less than .06 indicate acceptable fit for RMSEA and SRMR(Hu & Bentler, 1999).

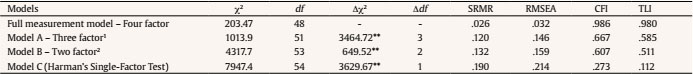

We first conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to confirm the distinctness of the study's measures in the samples. Besides the measurement model, which include the four correlated factors proposed in the study — CES, PI, CPand PE— a three-factor (including CES and PIinto a single factor) and two-factor (combining CA E, PI, and C Pinto a single factor) models were also tested. Among alternative models, the one-factor model where all variables were loaded on a single latent factor allowed for evaluating potential common method variance induced by the use of single informants by using Harman's test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The basic assumption of Harman's one-factor test is that if a substantial amount of common method variance is present, either a single factor will emerge from factor analysis or one general factor will account for the majority of covariance among measures, with all items loading on that single factor. In addition, we assessed measurement invariance of the scales used in the two samples. Literature has underscored the importance of establishing measurement equivalence for meaningful and reliable interpretation of group differences (such as mean scores and regression coefficient), even for groups from within the same culture (Steinmetz et al., 2009; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). In measurement invariance analysis, we progressively subject parameters (factor loading and indicator intercepts) to equality constraints, with each successive step retaining constraints from previous step. With each step, a change in CFI(DCFI) of less than or equal to .01 indicates invariance (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). As this study involve mainly comparison of the regression coefficient, establishing invariance of factor loading and indicator intercepts suffice, and we will not proceed further to test for invariance of residual variances, structural covariance, and structural means.

After ascertaining measurement invariance, we conducted multiple regressions using multi-group structural equation modelling (SEM). We favored using SEMtechnique for the regression as the estimates of relationships can be more accurate than a regular regression analysis in SPSS(McCoach et al., 2007). These SEMtechniques use multiple indicators to estimate the effects of latent variables and accounts for measurement error (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2006). Finally, we tested if unstandardized regression weights between the two groups are significantly different by calculating the Z score using the formula provided by Clogg et al. (1995):

This formula had been attested as the correct formula for the comparison of regression coefficients (Paternoster et al., 1998) as the estimate of the standard deviation of the sampling distribution is unbiased (Brame et al., 1998).

Results

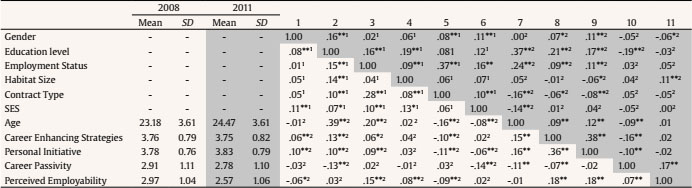

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Independent Variables

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables. Due to large sample sizes, normality was ascertained by checking skewness and kurtosis instead of using Shapiro-Wilk test, which is sensitive to large sample size (West et al., 1995). In general, skewness and kurtosis of items and composite scores were within ± 1.2, and was thus assumed normal as it did not exceed the recommended value of 2 (Garson, 2012). At this juncture, we note that PIand CPare not significantly correlated in 2008. CESand CPshowed a negative, but small, significant correlation (-.07 in 2008 and -.16 in 2011). Reversely, CESand PIshowed a moderate positive significant correlation (.36 in 2008 and .38 in 2011). Control variables appear significantly related with CES, PI, CP, and PEfor both samples. Women showed more CESand PIthan men, but less perceived employability, reflecting more difficulties for women to be employed in the Spanish labor market. Age and educational level are positively related with CESand PI, negatively related with CP, but not significantly related with PEThus, individuals who are more educated do not perceive themselves as more employable than less educated ones, probably reflecting a dual labor market, with separate opportunities for employment for different segments of the work force. Employed individuals showed more CES, PI, and PEthan unemployed ones. Socioeconomic status is negatively related with CP, but also with PI, which is counterintuitive in certain way. Finally, town population size is positively related with perceived employability, reflecting wider job opportunities in big cities than in small towns.

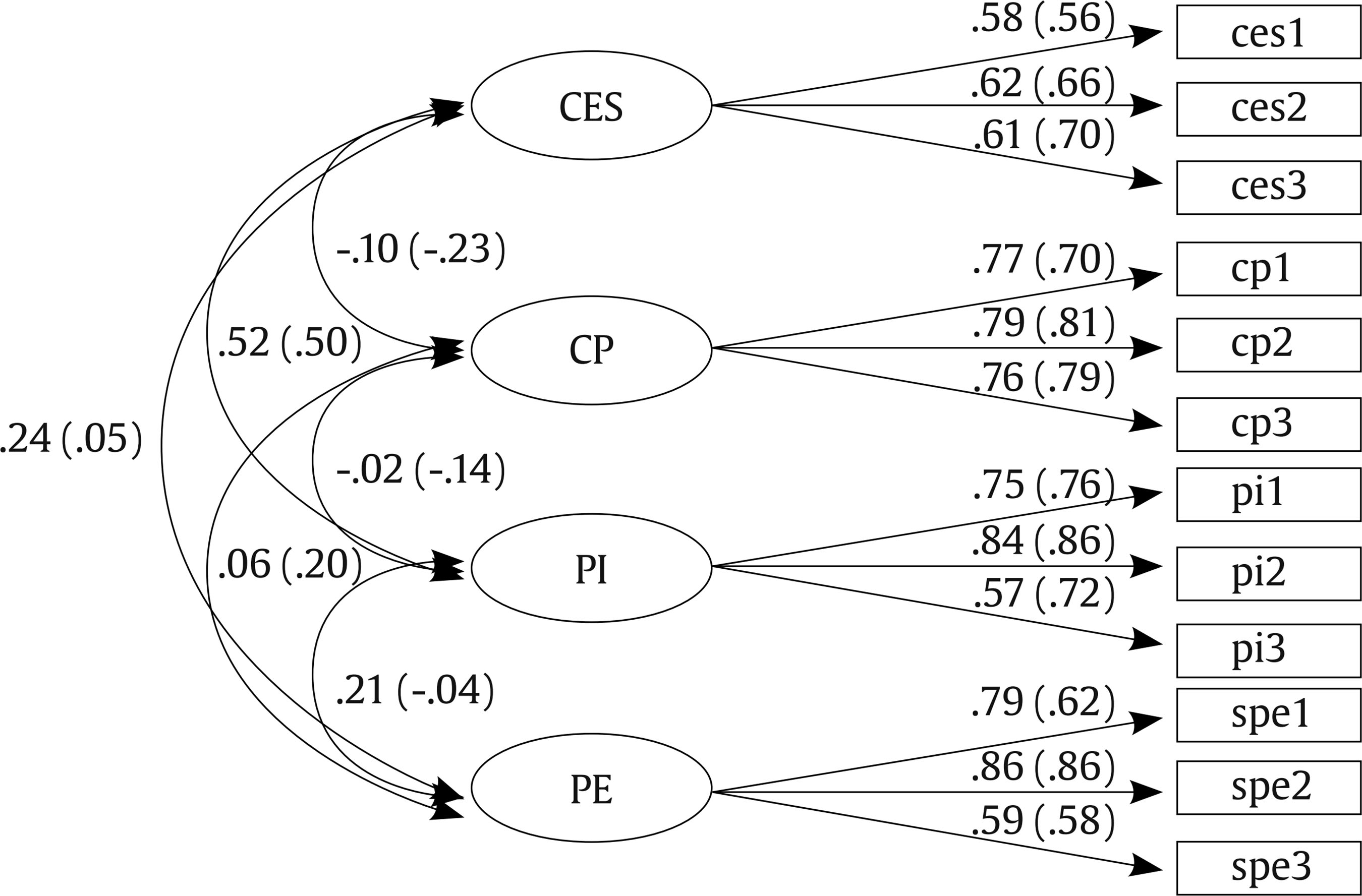

Test of Measurement Model

The full measurement model included four distinct factors: CES, PI, CP, and PEE ach indicator was specified to load only on the latent variable it was purported to measure, and all latent variables were allowed to correlate. All factor loadings were above the .50 threshold (between .57 and .87) and were significant at p< .001 (see Figure 1). The measurement model presented a good model fit: χ2(48) = 203.47, CFI= .99, TLI= .98, RMSEA = .032, SRMR= .026. Next, the full measurement model was compared to alternative models, as shown in Table 3. A three-factor model (Model A) was created to assess the distinctness of two personal resources (CESand PI) from CPand PEA two-factor model (Model B) was created to assess the distinctness of the three independent variables (CES, PI, and CP) from the PEFinally, we have a single-factor model, Model C, which also double up as Harman's one factor test that allowed for evaluating potential common method variance induced by the use of single informants. Fit indices of the alternative models presented unacceptable model fit (See Table 4) and only the full measurement model yielded good fit, hence indicating that full measurement model is superior. Results suggest that variables in this study are distinct and that items are significantly and substantially related to the expected latent factor.

Test for Multi-Group Measurement Invariance

To assess the measurement equivalence of the questionnaire across labor conditions, a multi-group CFA was conducted. The test of measurement invariance included only the invariance of factor loadings and factor intercepts as we are mainly interested in comparing the regression coefficient. We inspect the overall model fit and changes in fit statistics; a change in CFIof lesser than .01 indicates invariance (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Results demonstrated that invariance was achieved across labor conditions with both CFIand TLI> .95, RMESA = .026, SRMR= .038, and DCFI< -.01; the two groups responded to the questionnaire similarly across labor conditions.

Having ascertained that factor loadings and means are invariant across the two labor conditions, we then proceeded to test if sample means were significantly different from each other using independent sample t-tests. Results have shown that the mean of CPwas significantly higher in 2008 (M= 2.91, SD= 1.11) than in 2011 (M= 2.78, SD= 1.10), t(3198) = 3.12, p< .01. PEmean was also significantly higher in 2008 (M= 2.97, SD= 1.04) than in 2011 (M= 2.57, SD= 1.06), t(2521.18) = 10.44, p< .01. The t-tests helped us to understand the two samples and have indicated that means for personal resources except for CPwere comparable, and PEmeans were congruent with market trends. PEwas higher in 2008 because there were more job opportunities in 2008 than in 2011, and higher job opportunities gave rise to higher PEperception (Berntson et al., 2006). CPmeans were found to be significantly higher in 2008 and what seems to contradict the logic of hypothesis H2c. As this is an initial analysis to understand sample's responses and to check if PEmeans are congruent with market trends, we will address the observation in the Discussion section instead.

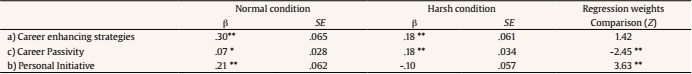

Regression Analysis and Coefficient Testing

Having ascertained measurement invariance, we proceeded to test the relationship between CES, CP, and PIon PEin two different labor conditions (nnormal= 1,992, nharsh= 1,208) while controlling for age, gender, education level, contract type, employment status, SES, and population size. The multiple regressions using multi-group structural equation modelling (SEM) presented a good model fit: χ2(368) = 724.34, CFI= .99, TLI= .97, RMSEA = .017. R2for the 2008 and 2011 structural model predicting perceived employability was .14 and .11 respectively. Standardized regression weights of all three personal resource variables were significant predictors of PEin normal condition (βCES= .19, p< .05; βPI= .12, p< .05; βCP= .07, p= .01); there was support for H1a, H1b, and H1c. As expected, relationships were positive (see Table 5). In the harsh condition, all except PIwere significant predictors of PEcondition (βCES= .14, p< .05; βPI= -.08, p= .09; βCP= .20, p< .05), hence H2b, which expected PIto gain predictive strength in harsh condition, was not supported.

Table 5. Standardized Regression Weights of Variables Predicting Perceived Employability and Comparison of Regression Weights

*p< .05

**p< .01.

We proceeded to compare the regression weights of the three predictors on PEbetween the two labor conditions. The difference between CESregression weights in the two labor conditions was not statistically significant (Z= 1.42, p> .05); there is no support for H2a..On the other hand, there was support for H2c as the difference between CPregression weights was statistically significant (Z= -2.45, p< .05); H2c was supported. Although PIwas not a significant predictor of PE and it did not gain predictive strength during harsh condition (i.e., H2b is not supported), we still proceeded the analysis to help us understand what might be happening. The analysis revealed that the difference between the PIregression weights in the two labor conditions was statistically significant (Z= 3.63, p< .05).

Discussion

This study aimed at establishing if personal resources in the form of career-enhancing strategies (CES), personal initiative (PI), and career passivity (CP) predict perceived employability (PE) differently in Spanish young adults during normal and harsh labor conditions. While the relationship between these three personal resources have been previously studied, they however tend to be studied in 'normal' labor conditions, i.e., mainly before the global economic crisis in 2008. The Spanish experience of the 2008 economic crisis gave rise to an opportunity to further examining if personal resources predicts PEdifferently in prolonged harsh labor conditions. Harsh labor conditions in this paper refer to the recession period during 2008-2012, where unemployment rates were high, and job vacancies were low. The aim was achieved through establishing that personal resources do predict perceived employability positively in normal conditions (H1a, H1b, and H1c) followed by establishing if personal resources gain predictive strength in predicting PEin harsh labor conditions (H2a, H2b, and H2c) by comparing their regression weights.

Overall, our results have demonstrated that the measurement model has a good model fit and both samples from normal and harsh labor conditions responded to the instrument similarly; the instrument was invariant. After controlling for covariates (age, gender, education level, employment status, employment type — permanent or temporary work —, total family income as an indicator of SES, and habitat size from which participants were from), results from the multi-group analysis indicate that both CESand CPpositively predict PEHowever, PIonly predicts PEduring normal condition. The analysis also shows CPas a better predictor of PEduring harsh conditions, compared with normal labor market conditions.

Career Enhancing Strategies

Results indicate that CESpredict PEsignificantly in both labor conditions. Our findings underscore the role of human capital resources in predicting PE and is consistent with previous research (Feldman, 1996; Harvey, 2001; McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005). Young people, who have invested more in developing their KSAOs,i.e., human capital, tend to possess more skills that are desirable and competencies that can contribute to employers' business objectives, and hence perceive themselves as more employable. This study did not find evidences indicating that CESgain predictive strength during harsh labor condition. Based on the initial t-test, we also note that young people placed similar efforts in CESduring normal and harsh labor conditions. The conservation of resources theory can support us in understanding this observation; young people are maintaining their efforts in accumulating human capital resources they can use to overcome unemployment and competition in the market as it was before during normal labor condition.

Personal Initiative

Results indicate that PIpredicts PEsignificantly in normal labor conditions. This finding is in agreement with existing research and verifies PIas an employability asset in the 21stcentury (Den Hartog & Belschak, 2007; Frese & Fay, 2001; Hillage & Pollard, 1999; Ohly et al., 2006). However, the above assertion does not hold in harsh labor conditions, such as the Spanish labor market in the 2008-2011 period. Taking into account the low job creation, the low job vacancy rate, and the high youth unemployment in the Spanish labor market, chances of securing a job interview may already be limited. Therefore, unless young people get pass the stage of job interviews, PImay not have an influence on one's possibility to obtain a job, to overcome career related goals, or to contribute to operational productivity, although PIis a personal attribute valued by employers. Results indicate that challenges faced by young people in the labor market may be beyond the influence of one's initiative and locus of control, suggesting that during harsh labor conditions, opportunities to maintain or get a job are more related with external conditions than with initiatives that youngsters could take.

Career Passivity

In total, our findings show that CPhas a stronger predictive weight during harsh labor conditions. Findings suggest that for young people entering the precarious, uncertain, and volatile labor market, like the 2008-2011 Spanish labor market, being less preoccupied in charting one's career direction gives a higher sense of perceived employability. Career passiveness in this context may allow young people to explore other options while in employment. It may also support young people to cope and transit to another job when the contract ends, as they do not have a resolute and eventual career plan. Results from test of means differences at the start of analyses have indicated that the mean for CPin 2011 was significantly lower than in 2008. Although career passiveness predicts perceived employability positively, young people were, in fact, less career passive in 2011 than in 2008. But perceptions about own employability remain are linked with openness to accept different opportunities, and not only linked with previously set goals. We attempt to understand this observation using the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991). This theory states that behavior is determined by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. In this scenario, attitude is the prospects of economic recovery and the knowledge of an overcrowded and competitive labor market; subjective norm is the need to be independent and be in employment, and behavioral control is the ease in accomplishing career planning. Therefore, young people may engage some career planning to be more successful in obtaining a job that they desire during market recovery. Nevertheless, career passivity, considered as lacking specific plans and expecting what happens to react in front of external conditions and offerings, increases the awareness of youngsters of being employable. These results are congruent with the social norm theory applied to unemployment and underemployment (Buffel at al., 2015), which "is based on the premise that economic conditions influence the extent to which an individual's position on the labor market is regarded as deviant" (Dudal & Bracke, 2019, p. 136). External conditions allow being passive as job opportunities are scarce. In such times, career passivity as being open and flexible to different options that could appear in the labor market could be an adaptive strategy for being employable.

Implications and Contributions

As the global labor market becomes increasingly dynamic, boundaryless, and ever-changing, demands for protean career attitudes will continue. Individuals will still require initiative and proactivity, continuous development, and personal responsibility in obtaining, developing, and maintaining their own career. Our study provides an insight into how changes in labor market conditions could affect personal resources and employability perceptions. Findings can be useful for career services to better support young people in coping and maintaining positive employability perceptions during harsh labor times. For example, career advisors and counsellors suggesting young people to exercise more personal initiative in job seeking may be less effective and may result in more frustration instead of supporting young adults in coping. In such scenario, promotion of initiative does not enable young adults to harness the 'protective' coping effect of PEin terms of protecting their self-concept and self-esteem on unemployment (McArdle et al., 2007). Instead, inviting young adults to use the chance to identify opportunities and possible career plans that arises from the situation or for market recovery, and to plan for possible scenarios ahead, i.e., to take a more active approach to plan for their future career might foster PERecapitulating that labor market for young people is sensitive to socioeconomic changes, we hope to encourage similar studies, so that young people can receive more targeted and perhaps an alternative form of support (at a more affective and cognitive level) when faced with harsh labor conditions. Most existing active labor market programs for young people are mainly skilled-based training or job search/insertion-based programs (see Card et al., 2010; Kluve, 2010), which may be of limited relevance to maintaining employability and coping with harsh conditions. Our results suggest that combining efforts to gain skills and experiences and being open and flexible regarding opportunities that labor market could offer with no previous plans will increase perceived employability during harsh labor conditions. Following the distinction of Vanhercke et al. (2014) with regard to internal and external factors referred to employability, it seems that during favorable economic and labor distinctions, internal factor predominate in shaping employability perceptions. Nevertheless, when economic and labor conditions are less favorable to employment, employability seems to rely more on external conditions than on skills and personal characteristics. The higher relevance of CPduring harsh labor conditions suggest that youngsters with more career passivity (who expects how that labor market evolves without taking initiative, and seems to be more flexible to accept different job opportunities) perceive themselves as more employable.

Limitations and Future Directions

The major limitation of this study is the impossibility of drawing any inferences on causality. This study comprised two independent cross-sectional samples. To be able to draw inferences about the antecedents of perceived employability, future research can consider utilizing longitudinal data with repeated measures. In addition, extending the length of the study to six years instead of three, and with multiple time points, may offer a more insightful understanding of the impact of harsh labor conditions. Another limitation of the study is the low percentages of explained variance of personal resources in perceived employability. Although the variables together explain only about 12% (13.4 % in 2008 and 10.3% in 2011) of variance, results do not rule out the predictor role of personal resource variables in this study. Nevertheless, the use of representative samples of Spanish youngsters in 2008 and 2011 provide some insight about the influence of labor market conditions on perceived employability. Moreover, despite the fact that other personal resources and the human capital indicator are excluded from this research, career planning and personal initiative have been relevant contents in many employability-enhancing programs. Clarifying its contribution to perceived employability should be relevant to career advisors and policy makers .

Future research can consider revising the scales and including more items for each scale in the study; the scales used in this study were selected in 1996 when the observatory study started. Finally, it will be interesting to study if career passivity differs in young people from different labor contexts, i.e., in a market that is less precarious for young people and with a lower percentage of young people engaging in temporary contracts to gain entry to the labor market.

Conclusion

In short, this study has verified that CES, PI, and CPare relevant to employability perception. In harsh labor conditions, like the ones Spain experienced during the past recession, CESis equally important to perceived employability but not PIWe postulate that due to limited job opportunities in harsh labor conditions, PIhas a diminished role in predicting perceived employability despite current protean and self-directed career environment demands for individuals with initiative and proactiveness. In the case of young adults in Spain, where precarious work tends to be the main vehicle for young people to gain entry during normal conditions, CPtakes on a more predictive role during harsh labor conditions. We postulate that career passivity allows Spanish young entrants to be more open and less exigent, and it may be a strategy to cope with market uncertainties and insecurities. This study broadens our knowledge on how harsh labor market conditions impacts personal resources and employability perception in Spanish young adults. Findings can be useful for career services, and we hope to spur similar studies so that young people can receive more targeted support during harsh labor condition.