Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acción Psicológica

versión On-line ISSN 2255-1271versión impresa ISSN 1578-908X

Acción psicol. vol.10 no.1 Madrid ene./jun. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.5944/ap.10.1.7040

Religious orientation and psychological well-being among spanish undergraduates

Orientaciones religiosas y bienestar psicológico de los estudiantes universitarios españoles

Joaquín García-Alandete y Gloria Bernabé Valero

Departamento de Metodología, Psicología Básica y Psicología Social, Universidad Católica de Valencia ximo.garcia@ucv.es

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes the relationship between intrinsic/extrinsic/quest religious orientation and psychological well-being in a sample of 180 Spanish undergraduates, 138 women (76.7%) and 42 men (23.3%), aged 18-55, M = 22.91, sD = 6.71. Spanish adaptations of the Batson and Ventis´ Religious Orientation Scaleand the Ryff´s psychological Well-Being Scales were used to this aim. The results of a multiple regression analysis showed (1) a positive relationship between the intrinsic orientation and the psychological well-being measures except for Autonomy, (2) a negative relationship between the extrinsic orientation and Autonomy, and (3) a negative relationship between the quest orientation, Self-acceptance and Purpose in life. The results are discussed in the light of previous researches.

Key words: Intrinsic religiosity, extrinsic religiosity, quest religiosity, psychological well-being, multiple regression.

RESUMEN

Se analiza la relación entre las orientaciones religiosas intrínseca/extrínseca/de búsqueda y el bienestar psicológico en una muestra de 180 universitarios españoles, 138 mujeres (76.7%) y 42 hombres (23.3%), con edades entre 18 y 55 anos, M = 22.91, DT = 6.71. Se usaron adaptaciones españolas de la Escala de orientación Religiosa, de Batson y Ventis, y las Escalas de Bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Los resultados de un análisis de regresión múltiple mostraron (1) una relación positiva entre la orientación intrínseca y las medidas de bienestar psicológico, excepto Autonomía, (2) una relación negativa entre la orientación extrínseca y Autonomía, y (3) una relación negativa entre la orientación de búsqueda, Autoaceptación y Propósito en la Vida. Los resultados se discuten a la luz de investigaciones previas.

Palabras clave: Religiosidad intrínseca, religiosidad extrínseca, religiosidad de búsqueda, bienestar psicológico, regresión múltiple.

Introduction

Several studies have reported positive relations among religiosity, psychological wellbeing, happiness, meaning in life, and mental health (Batson, Schoenrade & Ventis, 1993; García-Alandete, 2010; Hackney & Sanders, 2003; Koenig, 1998; Moreira-Almeida, Neto & Koenig, 2006; Paloutzian & Park, 2005; Pargament, 1997; Pargament et al., 1992). When assessing religiosity by means of variables such as religious self-identification, degree of personal religiosity, or frequency of attendance to worship and praying, among others, personal style of living religion might be as important, if not more, as to analyze its relationship with psychological well-being (Watson, Morris & Hood, 1992). Regarding this, Allport (1950) distinguished between a mature religiosity and an immature one. Mature religiosity was associated to the integration and organization of personality, consistent morality, and flexible and complex cognitive style, all this opposed to fanaticism and rigidity of thought. On the contrary, Allport related immature religiosity with self-gratification, which did not contribute to the integration of personality or self-reflection.

Later, Allport and Ross (1967) distinguished two religious orientations: intrinsic and extrinsic. The intrinsic orientation involves: the experience of religion as an end in itself and as a fundamental reason for life, the consideration of religion as an axis and absolute discretion in personal decisions, it is inclusive and source of existential sense, and it involves the internalization of the belief system, which is in harmony with the rest of the needs, these being considered less important though. Ultimately, intrinsic religiosity implies to live religion as a value and meaning. On the contrary, the extrinsic implies that religion is a means to achieve one´s interest and personal purposes (security, social status, entertainment, self-justification, life-style support, etc.). The belief system is superficially sustained and selectively fulfilled to meet more pragmatic and beneficial needs, then it is purely utilitarian and instrumental (Allport & Ross, 1967; Hunsberger, 1999; Nielsen, 1995). Allport considered both intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity as mutually exclusive, corresponding to the mature and immature religiosity, respectively. A sign of the maturity of the intrinsic orientation would be its negative relationship with prejudice, enmity, contempt, and intolerance, as opposed to the extrinsic, which is positively related with these attitudes (Allport, 1966; Allport & Ross, 1967).

On the other hand, Batson (1976) suggested three independent religious orientations, so that a person may score on the three: Means, End (both comparable to the extrinsic and intrinsic respectively, so that hereinafter they will called so), and Quest. To measure these religious orientations, Batson and Ventis (1982) developed the Religious Orientation Scale, of which a Spanish version was used in the present study, below described. Batson and Ventis (1982) used to build this scale (1) their Religious life Inventory, a 25-item questionnaire with three subscales that measures external (extrinsic), internal (intrinsic), and interational (quest) orientations, (2) their Doctrinal Orthodoxy Scale, a 12-item scale that measures the individual´s belief in the traditional religious doctrine, and (3) the Allport and Ross´ (1967) intrinsic-extrinsic scale. By means of a Principal Components Analysis using these scales, Batson and Ventis (1982) obtained the Religious Orientation Scale.

The quest orientation is characterized as not dogmatic but flexible and by a fundamental question about the whole existence without reducing its complexity, a positive experience of the religious matters, and an openness to change regarding religious matters. Batson considers that quest orientation is mature and the intrinsic is immature (dogmatic and inflexible). As a sign of the maturity, Batson (1976) obtained positive relationships between the quest orientation and prosocial behavior (compassion), whereas the same author, along with Batson, Naifeh, and Pate (1978) found a negative relationship between racial prejudice and discrimination (greater than at the other two religious orientations), which would control the effect of social desirability.

However, Ventis (1995) obtained (1) that intrinsic orientation was positively related to appropriate social behavior, self-acceptance and self-actualization, unification and organization of the personality, as well as opening and mental flexibility; he also found out (2) that extrinsic orientation was predominantly related to these variables in a negative way, and (3) that quest orientation (although less thoroughly studied) gave rise to mixed results. In addition, intrinsic orientation related negatively to mental illness, concern, and guilt, as Allport (1966) found, too. These patterns of relationships have been obtained with different measures of psychosocial health, including psychological well-being, showing that intrinsic orientation is positively related, unlike extrinsic and quest (Genia, 1996; Genia & Shaw, 1991; Griffin, 2002; Holt, Clark & Klem, 2007; Lewis, Maltby& Day, 2005; Maltby, Lewis & Day, 1999, 2000, 2003; Maltby & Day, 2004; Mela et al., 2008; Salmanpour & Issazadegan, 2012; Saroglou, 2002; Worthington, Kurusu, McCullogh & Sandage, 1996).

With the exception of Ramírez (2006), Núnez, Moral, and Moreno (2010), Núnez-Alarcón, Moreno-Jiménez, and Moral-Toranzo, (2011), and Núnez, Moreno, Moral, and Sánchez (2011), we have not found any more studies targeting at Spanish population in which the Religious Orientation Scale (Batson & Ventis, 1982) was used. None of those papers is about the relationship between religious orientation and psychological well-being either. Despite its relevance and being extensively investigated in other countries, it remains an unattended issue in Spain. This circumstance increases the interest of this work, whose objective is to analyze the relationship between the religious orientation and the psychological well-being in a sample of Spanish undergraduates. The hypothesis that we propose is that intrinsic orientation relates positively to psychological well-being, while extrinsic and quest relate negatively.

Method

Study participants

The study included 180 Spanish undergraduates, 138 women (76.7%), and 42 men (23.3%), both groups aged from 18 to 55 years, M = 22.91, SD = 6.71. All of them were recruited by incidental sampling. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and participants did not receive any compensation for it. They were given appropriate instructions for the fulfillment of the protocol, which included the scales described below.

Instruments

Religious Orientation Scale (ROS; Batson & Ventis, 1982). We used the Ramírez´s (2006) Spanish adaptation, a 27-item scale Likert-type (1 = Strongly disagree, 9 = Strongly agree) that identifies intrinsic, extrinsic, and quest religious orientations as independent dimensions, which means that individuals would score in all of them.

Scales of Psychologycal Well-Being (SPWB; Ryff, 1989a, 1989b). A Spanish adaptation by Díaz et al. (2006) was used, a 29-item scale Likert-type (1 = Strongly disagree, 6 = Strongly agree) that assesses the psychological wellbeing understood as personal development and commitment to the existential life challenges. It works through six scales: Self-acceptance (positive attitudes toward oneself), Positive Relations (warm, trusting interpersonal relations and strong feelings of empathy and affection), Autonomy (self-determination, independence, internal locus of control, individuation, and internal regulation of behaviour), Environmental Mastery (ability to choose or create environments suitable to his or her psychic conditions), Personal Growth (continuing ability to develop one´s potential, to grow and expand as a person), and Purpose in Life (clear comprehension of life´s purpose, sense of directedness, and intentionality) (Keyes, Shmotkin & Ryff, 2002; Ryff, 1989a, 1989b; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Ryff & Singer, 1998, 2008).

Procedure and analysis

Participants fulfilled the protocol, which included the scales of religious orientation and psychological well-being, in the classrooms in which they usually developed their academic activities and under our supervision. The average time to fill out the protocol was 30 minutes approximately. The anonymity and confidentiality of the data were emphasized, and the doubts about the procedure for completing the protocol were solved.

SPSS 15.0 for Windows was used for the descriptive statistics and the estimation of the internal consistency (Cronbach´s alpha) of the scales. A multiple regression with all variables entered simultaneously was used to test the hypothesis.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and the internal consistency of the scales. The Cronbach´s alpha values ranged from acceptable to excellent (Grounlund, 1985; Nunnally, 1978).

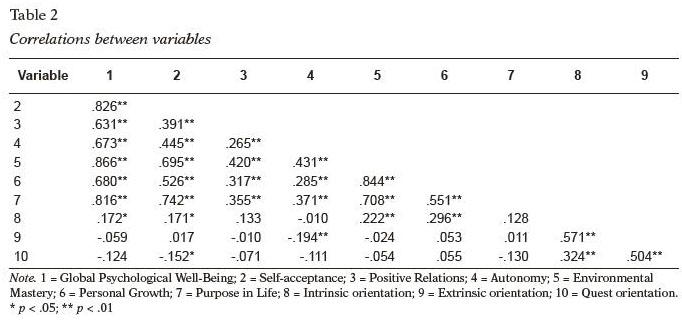

Table 2 shows the correlations between the religious orientations and the dimensions of psychological web-being.

A multiple regression with intrinsic, extrinsic, and quest religious orientations entered simultaneously showed that were explained the 3.6% of Positive Relations, the 5% of Purpose in Life, the 5.3% of Autonomy, the 7.7% of Self-acceptance, the 8.2% of Global Psychological Well-Being, the 8.7% of Environmental Mastery, and, the 10.8% of Personal Growth. That is, a small size of the R2 effect (Cohen, 1988) (table 3).

Except for Positive Relations, F(3, 176) = 2.177, p =.092, the regression models were significant for Global Psychological Well-Being, F(3, 176) = 5.206, p = .002, Self-acceptance, F(3, 176) = 4.925, p = .003, Autonomy, F(3, 176) = 3.290, p = .022, Environmental Mastery, F(3, 176) = 5.587, p = .001, Personal Growth, F(3, 176) = 7.116, p = .000, and Purpose in Life, F(3, 176) = 3.061, p = .030.

Table 4 shows the regression coefficients of the models. The non-standardized B coefficient was positive for the relationship between the intrinsic orientation and all the measures of psychological well-being, and negative for all the relationships between the extrinsic orientation and these measures. In the case of quest orientation, the non-standardized B coefficients were negative, except for Personal Growth, which was positive. That means that psychological well-being increased with the intrinsic orientation and decreased with the extrinsic and quest orientations (except for the last, at Personal Growth). However, only the regression equations corresponding to the relationships between (1) Global Psychological Well-Being, Positive Relations, Environmental Mastery, Personal Growth, and intrinsic orientation, (2) Autonomy and extrinsic (negatively), and (3) Self-acceptance, Purpose in Life, intrinsic (positively) and quest (negatively), were significant.

Since the results of the regression were little powerful, the differences in psychological wellbeing among extreme groups in the three religious orientations -that is, purest profileswere analyzed. The cut-off points to form the groups were established by the means and standard deviation (+/-1 SD). Table 5 shows the descriptive statistics and the test of equality of group means of the three religious orientations. There was significant the difference in Environmental Mastery between the extreme groups of the intrinsic religious orientation, t(101) = 2.097, p = .038. The group of less intrinsic religiosity showed more Environmental Mastery.

Discusión

The objective of this work was to analyze the relationships between religious orientation and psychological well-being in a sample of Spanish undergraduates, using the Spanish adaptations of the Batson and Ventis´ Religious Orientation Scales (Ramírez, 2006) and the Ryff´s Scales of Psychological Well-Being (Díaz et al., 2006). We hypothesized that the intrinsic orientation would be positively related to the psychological well-being and, on the other hand, extrinsic and quest orientations would be negatively related. A multiple regression analysis with enter method was conducted to test this hypothesis.

Our results support the hypothesis and coincide with studies that from decades ago reported positive relationships between intrinsic religiosity and well-being, and negative or non significant relationships between psychological well-being and extrinsic religiosity (Allport & Ross, 1967; Batson & Ventis, 1982; Batson et al., 1993; Bergin, 1991; Donahue, 1985; Griffin, 2002; Holt et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2005; Maltby et al., 1999, 2000, 2003; Mela et al., 2008; Ventis, 1995; Wigert, 2002; Worthington et al., 1996). These results would also endorse Allport´s concept of intrinsic religiosity as mature.

Although with small sizes of regression coefficients (Cohen, 1988), intrinsic orientation was significantly related with the measures of psychological well-being, except for Autonomy, β = .151, p = .093. On the contrary, extrinsic orientation showed negative relationships with all measures of psychological wellbeing, although, as noted, only the relationship with Autonomy, β = .267, p = .007 was statistically significant. That is, the individuals more extrinsically orientated have less sense of selfdetermination, perception of control of life, and a greater sense of being under the circumstances conditioning. They need to be positively valued and accepted within the religious community and so they depend a lot on the others´ opinion about them.

Why intrinsic orientation is not significantly related to Autonomy? We don´t have evidence of a suppressor effect or know what variable(s) fully mediate a previously significant relationship. In this case, we can´t say why the variables are uncorrelated, but a hypothesis could be that the intrinsically oriented individuals, that is, individuals with internal religious convictions, believe that God and His Providence are significant aspects of the existence. One´s own life is not independent of God, who would have an absolute value. For someone with an intrinsic religiosity, God´s will and moves must be respected and taken into account. Autonomy would be subtle in the intrinsic believer bacause of avoidance of self-sufficiency. On the other hand, the relationship between intrinsic orientation and Autonomy would be mediated as well since the intrinsically oriented individual takes others into account, just under his religious beliefs, without losing personal autonomy. In short, Autonomy is subtle at the intrinsic believer because of his own sense of personal dependence on God and his consideration towards the others.

Moreover, quest orientation showed a negative relationship with all the measures of psychological well-being, although it was only significant regarding Self-acceptance, β = .228, p = .007, and Purpose in Life, β = .192, p = .026. This religious orientation would not be a mature religiosity, contrary to what was stated by Batson and others (Batson, 1976; Batson et al., 1978, 1993; Batson & Raynor-Prince, 1983; Batson & Schoenrade, 1991a, 1991b; Batson & Ventis, 1982; Burris, 1994; Hunt & King, 1971; McFarland & Warren, 1992). This is supported by works that report relationships between quest orientation and the primary traits related to neuroticism (Hills, Francis, Argyle & Jackson, 2004), schizotypal traits (Joseph, Smith & Diduca, 2002), and religious conflict and anxiety (Kojetin, McIntosh, Bridges & Spilka, 1987; Spilka, Hood & Gorsuch, 1985). In addition to what was said, the negative relationship between quest and Self-acceptance and Purpose in Life can be explained because this religious scale involves a continuous process of doubt and rethinking of important aspects of self and life, as well as the positive assessment of this continuous questioning and review. It could be conceptually close to the idea of crisis in the development of identity (Erikson, 1997; Marcia, 2002). According to these authors, in the formation of personal identity, individuals go through stages of crisis, which are considered as a process of exploration of alternatives, so when a person finds a satisfactory option he or she is able to undertake and achieve his or her identity. Particularly in the religious sphere, the moratorium (exploration of alternatives) could resemble the contents of the quest scale. By contrast, Self-acceptance and Purpose in Life would relate to the acceptance of experiences, achievements, and vital objectives, that is, with issues significantly related to achievement of identity. Our results suggest that participants who scored higher in quest orientation could be in a process of moratorium in terms of self-image and vital goals and purposes. These results may be more important in adolescent and young adult populations, who possibly still have not finalized their process of exploration of the religious matters and, therefore, the achievement of their identity.

However, one should be cautious with the conclusions since the quest scale might have a poor fit and create validity problems (Beck, Baker, Robbins & Dow, 2001; Beck & Jessup, 2004; Donahue, 1985; Edwards, Hall & Slater, 2002; Núnez, Moreno, Moral & Sánchez, 2011; Watson et al., 1992). Interpretation of the items may be personal and they can be interpreted as religious or as anti-religious: in individuals with strong religious commitment this scale was strongly associated with well-being, while this was not the case in those who did not have this religious commitment and, therefore, interpreted the scale differently. This would explain why previous research has found mixed results. For example, quest orientation has been related to spiritual well-being, being this relationship mediated by development of identity and personal meaning (Klaassen & McDonald, 2002), as well as development of moral reasoning, specifically with postconventionality (Sapp & Gladding, 1989).

The cultural context might significantly influence the relationship between religious orientation and psychological well-being. Colbert (2004) did not obtain significant correlations between the religious orientation and the psychological variables associated with wellbeing in an African American sample. Lavric and Flere (2008) concluded in a cross-cultural study that Religious Orientation Scales are not entirely applicable to the majority of the observed cultures, and that every culture is characterized by a different relationship between religiosity and well-being: this relationship is stronger in societies with a higher level of religiosity. In the Spanish sociological context, according to some studies (e.g., González-Anleo & González, 2010), religion is undergoing a rapid and pronounced decline in recent decades, which might explain the low percentages of explained variance of psychological well-being in our study. Within a society suffering a fast and thorough process of secularization, young people turn to other sources of well-being different than religion. As Christopher (1999) pointed out, psychological well-being is strongly conditioned by the socio-cultural context, and religion is an important component of this. All of this indicates the desirability, if not the need, to deepen in the conceptualization of the religious orientations in the light of the social reality, which is dynamic and changing. Likewise, it is necessary to deepen in the study of the religious phenomenon and its relationship with several psychosocial variables from a cross-cultural perspective (Flere, Edwards & Klanjsek, 2008; Núnez, Moral & Moreno, 2010).

In addition to the possible sociological variables that could influence the relationships between religious orientation and psychological well-being, it would be advisable to analyze the role of other individual variables that could mediate, such as frequency of praying, importance of God in life, and importance of religion in life (Maltby et al., 1999; Saroglou & Mathijsen, 2007), as well as meaning in life (George, Ellison & Larson, 2002; Steger & Frazier, 2005), motivation and the social-cognitive schemes (Neyrinck, Lens, Vansteenkiste& Soenens, 2010), or the affective, cognitive, and conative components of attitudes toward religious beliefs and practices (Kristensen, Pedersen & Williams, 2002). Possibly these or other variables might explain that less intrinsic religiosity is associated to more Environmental Mastery, that is, (1) a sense of competence in managing the environment, (2) to control complex array of external activities, (3) to make effective use of surrounding opportunities, and (4) ability to choose or create contexts suitable to personal needs and values (Ryff and Keyes, 1995). More intrinsic religiosity could difficult the achievement of a sense of control over the environment. The degree of intrinsic religiosity was not significant for the rest of scales of psychological well-being. Furthermore, the degree of extrinsic religiosity and quest was not significant in relation to psychological well-being.

Without prejudice to its contributions, we can point out some limitations in this study. First, the sample is only made up of undergraduates. Future studies should consider more representative samples of the population, diverse and heterogeneous samples, such as samples belonging to different cultures and religions (e.g., Johnstone et al., 2012). Likewise, it would be important to count on several measures of religiosity, spirituality, well-being, and mental health, to have both more elements of contrast and offer more significant conclusions about their relationships. It would also be interesting to carry out statistical analyses which would report not predictively (such as the regression model), but causally (such as the path analysis or the structural equation modeling) about the relationships between religiosity (assessed in its various dimensions, and in its degree) and psychological well-being and other measures of mental health, including the variables that could mediate.

References

1. Allport, G. W. (1950). The individual and his religion. New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

2. Allport, G. W. (1966). Religious context of prejudice. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 5, 447-457. doi:10.2307/1384172. [ Links ]

3. Allport, G. W. & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personalit y and Social Psychology, 5, 432-433. doi:10.1037/h0021212. [ Links ]

4. Batson, C. D. (1976). Religion as Prosocial: Agent or Double Agent? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 15, 29-45. doi:10.2307/1384312. [ Links ]

5. Batson, C. D. & Raynor-Prince, L. (1983). Religious Orientation and Complexity of Thought Ab ou t Existential Concern. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 22, 38-50. doi:10.2307/1385590. [ Links ]

6. Batson, C. D. & Schoenrade, P. (1991a). Measuring religion as quest: 1) Validity concerns. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 416-429. doi:10.2307/1387277. [ Links ]

7. Batson, C. D. & Schoenrade, P. (1991b). Measuring Religion as Quest: 2) Reliability Concerns. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 430437. doi:10.2307/1387278. [ Links ]

8. Batson, C. D. & Ventis, W. L. (1982). The religious experience: A social-psychological perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

9. Batson, C. D., Naifeh, S. J. & Pate, S. (1978). Social desirability, religious orientation, and racial prejudice. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 17, 31-41. doi:10.2307/1385425. [ Links ]

10. Batson, C. D., Schoenrade, P. & Ventis, W. L. (1993). Religion and the Individual: a social-psychological perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

11. Beck, R. & Jessup, R. (2004). The multidimensional nature of Quest motivation. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 32, 283-294. [ Links ]

12. Beck, R., Baker, L., Robbins, M. & Dow, S. (2001). A second look at Quest motivation: Is Quest unidimensional or multidimensional? Journal of Psychology and Theology, 29, 148-157. [ Links ]

13. Burris, C. T. (1994). Curvilinearity and Religious Types: A Second Look at Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Quest Relations. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 4(4), 245-260. doi:10.1207/s15327582ijpr0404_5. [ Links ]

14. Christopher, J. C. (1999). Situating Psychological Well-Being: Exploring the Cultural Roots of Its Theory and Research. Journal of Counseling and Development , 77 (2), 141-152. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02434.x. [ Links ]

15. Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

16. Colbert, L. K. (2004). A study of religiosity and psychological well being among African Americans: Implications for counseling and psychotherapeutic processes. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 64(12-A), 43-54. [ Links ]

17. Díaz, D., Rodríguez-Carvajal, R., Blanco, A., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Gallardo, I., Valle C. & van Dierendonck, D. (2006). Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff (Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBS)). Psicothema, 18(3), 572-577. [ Links ]

18. Donahue, M. J. (1985). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 400-419. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.2.400. [ Links ]

19. Edwards, K. J., Hall, T. W. & Slater, W. (2002, August). The structure of the quest construct. Paper presented at the American Psychological Association convention, Chicago. [ Links ]

20. Erikson, E. H. (1997). The live cycle completed. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company. [ Links ]

21. Flere, S., Edwards, K. J. & Klanjsek, R. (2008). Religious Orientation in Three Central European Environments: Quest, Intrinsic, and Extrinsic Dimensions. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 18, 1-21. doi:10.1080/10508610701719280. [ Links ]

22. García-Alandete, J. (2010). Psicología positiva, felicidad y religión (Positive psychology, happiness, and religion). Religión y Cultura, 253-254, 523-548. [ Links ]

23. Genia, V. (1996). I, E, Quest, and Fundamentalism as Predictors of Psychological and Spiritual Well-Being. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 35(1), 56-64. doi:10.2307/1386395. [ Links ]

24. Genia, V. & Shaw, D. G. (1991). Religion, Intrinsic-Extrinsic Orientation and Depression. Review of Religious Research, 32(3), 274-283. doi:10.2307/3511212. [ Links ]

25. George, L. K., Ellison, C. G. & Larson, D. B. (2002). Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 190-200. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1303_04. [ Links ]

26. González-Anleo, J. & González, J. (2010). Jóvenes españoles 2010 (Young spanish 2010). Madrid: España: Fundación SM. [ Links ]

27. Griffin, G. A. (2002). Creativity and religious orientation: An interactional study of psychological wellbeing. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 63(2-B), 1026. [ Links ]

28. Grounlound, N. E. (1985). Measurement and Evaluation in Teaching. New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

29. Hackney, C. H. & Sanders, G. S. (2003). Religiosity and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(1), 43-55. doi:10.1111/1468-5906.t01-1-00160. [ Links ]

30. Hills, P., Francis, L. J., Argyle, M. & Jackson, C.J. (2004). Primary personality trait correlates of religious practice and orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(1), 61-73. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00051-5. [ Links ]

31. Holt, C. L., Clark, E. M. & Klem, P. R. (2007). Expansion and Validation of the Spi ritual Health Locus of Control Scale. Journal of Health Psychology, 12(4), 597-612. doi:10.1177/1359105307078166. [ Links ]

32. Hunsberger, B. (1999). Social-psychological causes of faith; new findings offer compelling clues. Free Inquiry, 19(3), 34-38. [ Links ]

33. Hunt, R. A. & King, M. B. (1971). The intrinsicextrinsic concept: A review and evaluation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 10(4), 339-356. doi:10.2307/1384780. [ Links ]

34. Johnstone, B., Yoon, D. P., Cohen, D., Schopp, L. H., McCormack, G., Campbell, J. & Smith, M. (2012). Relationships Among Spirituality, Religious Practices, Personality Factors, and Health for Five Different Faith Traditions. Journal of Religion and Health, May 23 (Epub ahead of print). doi:10.1007/s10943-012-9615-8. [ Links ]

35. Joseph, S., Smith, D. & Diduca, D. (2002). Religious orientation and its association with personality, schizotypal traits and manic-depressive experiences. Mental Health, Religion and Culture,5(1), 73-81. doi:10.1080/13674670110112721. [ Links ]

36. Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D. & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007-1022. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.82.6.1007. [ Links ]

37. Klaassen, D. W. & McDonald, M. J. (2002). Quest and identity development: Re-examining pathways for existential search. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 12(3), 189-200. doi:10.1207/S15327582IJPR1203_05. [ Links ]

38. Koenig, H. (1998). Handbook of Religion and Mental Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [ Links ]

39. Kojetin, B. A., McIntosh, D. N., Bridges, R.A. & Spilka, B. (1987). Quest: Constructive search or religious conflict? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 26, 111-115. doi:10.2307/1385845. [ Links ]

40. Kristensen, K. B., Pedersen, D. M. & Williams, R. N. (2002). Profiling religious maturity: The relationship of religious attitude components to religious orientations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(1), 75-86. [ Links ]

41. Lavric, M. & Flere, S. (2008). The role of culture in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 47(2), 164-175. [ Links ]

42. Lewis, C., Maltby, J. & Day, L. (2005). Religious orientation, religious coping and happiness among UK adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(5), 1193-1202. doi:10.1016/j. paid.2004.08.002. [ Links ]

43. Maltby, J. & Day, L. (2004). Should never the twain meet? Integrating models of religious personality and religious mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1275-1290. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00215-0. [ Links ]

44. Maltby, J., Lewis, C. & Day, L. (1999). Religious orientation and psychological well-being: The role of the frequency of personal prayer. British Journal of Health Psychology, 4(4), 363-378. doi:10.1348/135910799168704. [ Links ]

45. Maltby, J., Lewis, C. & Day, L. (2000). Depressive symptoms and religious orientation: Examining the relationship between religiosity and depression within the context of other correlates of depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(2), 383-393. doi:10.1016/S01918869(99)00108-7. [ Links ]

46. Maltby, J., Lewis, C. & Day, L. (2003). Religious orientation, religious coping and appraisals of stress: Assessing primary appraisal factors in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(7), 1209-1224. doi:10.1016/ S0191-8869(02)00110-1. [ Links ]

47. Marcia, J. E. (2002). Identity and psychosocial development in adulthood. Identity, 2, 7-28. doi:10.1207/S1532706XID0201_02. [ Links ]

48. McFarland, S. G. & Warren, J. C. (1992). Religious Orientations and Selective Exposure among Fundamentalist Christians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 31(2), 163-174. doi:10.2307/1387006. [ Links ]

49. Mela, M. A., Marcoux, E., Baetz, M., Griffin, R., Angelski, C. & Deqiang, G. (2008). The effect of religiosity and spirituality on psychological well-being among forensic psychiatric patients in Canada. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 11(5), 517-532. doi:10.1080/13674670701584847. [ Links ]

50. Moreira-Almeida, A., Neto, F. L. & Koenig, H. G. (2006). Religiosidade e saúde mental: Uma revisão (Religiousness and mental health: A review). Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 28(3), 242-250. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462006005000006. [ Links ]

51. Neyrinck, B., Lens, W., Vansteenkiste, M. & Soenens, B. (2010). Updating Allport´s and Batson´s Framework of Religious Orientations: A Reevaluation from the Perspective of SelfDetermination Theory and Wulff´s Social Cognitive Model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49(3), 425-438. doi:10.1111/j.14685906.2010.01520.x. [ Links ]

52. Nielsen, M. E. (1995) Operationalizing Religious Orientation: Iron Rods and Compasses. The Journal of Psychology, 129(5), 485-494. doi:10.1 080/00223980.1995.9914921. [ Links ]

53. Núnez, M., Moral, F. & Moreno, M. P. (2010). Impacto diferencial de la religión en el prejuicio entre muestras cristianas y musulmanas (Differential impact of religion on prejudice in Muslim and Christian samples). Escritos de Psicología, 3(4), 11-20. [ Links ]

54. Núnez, M., Moreno, M. P., Moral, F. & Sánchez, M. (2011). Validación de una escala de orientación religiosa en muestras cristiana y musulmana (Validation of a scale of religious orientation in Christian and Muslim samples). Metodología de Encuestas , 13, 97-119. [ Links ]

55. Núnez-Alarcón, M., Moreno-Jiménez, M. P. & Moral-Toranzo, F. (2011). Modelo causal del prejuicio religioso (Causal model of religious prejudice). Anales de psicología, 27(3), 852-861. [ Links ]

56. Nunnaly, J. (1978). Psychometric Theory. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

57. Paloutzian, R. F. & Park, C. L. (2005). Handbook of the psychology of Religion and spirituality. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

58. Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

59. Pargament, K. I., Olsen, H., Reilly, B., Fal gout, K., Ensing, D. S. & Van Haitsma, K. (1992). God Help Me (II): The Relationship of Religious Orientations to Religious Coping with Negative Life Events. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 31(4), 504-513. doi:10.2307/1386859. [ Links ]

60. Ramírez, M. C. (2006). Una adaptación española de la Escala de Orientación Religiosa de Batson y Ventis (A Spanish adaptation of the Batson and Ventis´s Religious Orientation Scale). Revista de Psicología General y Aplicada, 59(1-2), 309-318. [ Links ]

61. Ryff, C. D. (1989a). Happiness is Everything, or is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069-1081. doi:10.1037//00223514.57.6.1069. [ Links ]

62. Ryff, C. D. (1989b). Beyond Ponce de Leon and Life Satisfaction: New Directions in Quest of Successful Aging. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12, 35-55. doi:10.1177/016502548901200102. [ Links ]

63. Ryff, C. & Keyes, C. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719-727. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [ Links ]

64. Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. H. (1998). The Contours of Positive Human Health. Psychological Inquiry, 9(1), 1-28. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0901_1. [ Links ]

65. Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13-39. doi:10.1007/ s10902-006-9019-0. [ Links ]

66. Salmanpour, H. & Issazadegan, A. (2012). Religiosity Orientations and Personality Traits with Death Obsession. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 4(1), 150-157. doi:10.5539/ijps.v4nlpl50. [ Links ]

67. Sapp, G. L. & Gladding, S. T. (1989). Correlates of religious orientation, religiosity, and moral judgment. Counseling and Values, 33(2), 140-145. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.1989.tb00753.x. [ Links ]

68. Saroglou, V. (2002). Religion and the five factors of personality: a meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 15-25. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00233-6. [ Links ]

69. Saroglou, V. & Mathijsen, F. (2007). Religion, multiple identities, and acculturation: A study of Muslim immigrants in Belgium. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 29, 177-98. doi:10.1163/008467207X188757. [ Links ]

70. Spilka, B., Hood, R. W. & Gorsuch, R. L. (1985). The psycholog y of religion: An empirical approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

71. Steger, M. F. & Frazier, P. (2005). Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to wellbeing. Journal of Counseling Pyschology, 52, 574-582. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.574. [ Links ]

72. Ventis, W. L. (1995). The Relationships Between Religion and Mental Health. Journal of Social Issues, 51(2), 33-48. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01322.x. [ Links ]

73. Watson, P. J., Morris, R. J. & Hood, R. W. (1992). Quest and identity within a religious ideological surround. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 20(4), 376-388. [ Links ]

74. Wigert, L. R. (2002). An investigation of the relationships among personality traits, locus of control, religious orientation, and life satisfaction: A path analytical study. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 62(10-B), 4828. [ Links ]

75. Worthington, E. L., Kurusu, T. A., McCullogh, M. E. & Sandage, S. J. (1996). Empirical research on religion and psychotherapeutic processes and outcomes: A 10-year review and research prospectus. Psychological Bulletin, 119(3), 448-487. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.119.3.448. [ Links ]

Recibido: 05-02-2013

Aceptado: 25-04-2013