Introduction

The pursuit of meaningful living is a longstanding concept, and recently psychologists have attempted to address the gap of understanding this concept with reliable and validated tools (e.g., Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006). Meaning in life (i.e., meaning) is a complex and multifaceted concept widely defined as the emotional and cognitive inquiry of whether one's life has value and purpose (Steger, 2009). Damon (2008) described today's North American young adults as “directionless drifters” who are living increasingly empty, meaningless lives. Converging evidence suggests that present-day college students are expressing greater need for personal fulfilment through achieving a sense of meaningful living (Higher Education Research Institute, 2004; Howe & Strauss, 2000; Lancaster & Stillman, 2002). In a survey conducted across 236 American colleges, 76 % of 112,232 college students indicated they were searching for meaning and a purpose in life (A. W. Astin et al., 2005). Presence of meaning (i.e., presence) is associated with a plethora of desirable outcomes, including greater wellbeing, longevity, positive affect, and satisfaction with life, while experiencing lower psychological distress (Boyle, Barnes, Buchman, & Bennett, 2009; Debats, Van der Lubbe, & Wezeman, 1993; Hicks & King, 2007; King, Hicks, Krull, & Del Gaiso, 2006; Melton & Schulenberg, 2008; Steger et al., 2006). Moreover, presence acts as a protective factor against substance abuse, depression, and suicidal ideation, with evidence suggesting higher scores on the purpose in life test can discriminate psychiatric patients from the normal population (Batthyany & Russo- Netzer, 2014; Brassai, Piko, & Steger, 2011; Heisel, Flett, Duberstein, & Lyness, 2005; Junior, 1999; Kinnier, Metha, Keim, & Okey, 1994). Presence is associated with a number of growth-related variables that allow healthy psychological functioning.

While there is a common misconception that search for meaning (i.e., search) is indicative of absence of meaning, factor analytic and multitrait-multimethod matrix analyses reveal that search and presence of meaning are independent and distinct concepts (e.g., Steger et al., 2006). Presence is defined as the extent to which an individual experiences meaning in one's life, while the search for meaning refers to an individual's drive and orientation to establish meaning in life (Batthyany & Russo-Netzer, 2014; Steger, 2009). Frankl (1963) described the search for meaning as the primary motivational force in human living and noted several benefits of this pursuit, such as happiness and the capability to cope with suffering. However, previous research has found that search for meaning is negatively associated with presence of meaning and measures related to psychological well-being (Park, 2010; N. Park, M. Park, & Peterson, 2010; Steger, Kashdan, & Oishi, 2008). For instance, individuals high in search for meaning tend to report greater rumination, negative orientation towards the past, and depressive symptoms (Steger et al., 2006; Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan & Lorentz, 2008).

Increasing research has demonstrated that differences between people may impact search for meaning and thus, produce differential outcomes in presence of meaning and well-being (Steger et al., 2006; Steger, Kashdan, & Oishi, 2008; Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan, & Lorentz, 2008). The function of search can change depending on situational and cultural context, with supportive social environments and collectivist cultures reporting positive associations between presence and search (Shin & Steger, 2016; Steger, Kawabata, Shimai, & Otake, 2008). Moreover, C. L. Park et al. (2010) proposed that search only predicts greater presence and well-being when the individual already has high presence of meaning. A recent longitudinal diary study found that presence of meaning mediated positive relationships between search and well-being, while simultaneously suppressing negative direct relationships between search and well-being (Newman, Nezlek, & Thrash, 2017).

Resiliency allows an individual to overcome and thrive in the face of obstacles or adversity in his environment and has been shown to be positively associated with life satisfaction (Masten, 2001, 2007, 2014; Samani, Jokar, & Sahragard, 2007). While search for meaning may allow an individual to ultimately find meaning and thrive, the search for meaning is, inevitably, associated with distress as it may be a difficult process accompanied with certain challenges (Wong, 2012). Individuals with higher internal resources of resiliency, which is defined as a multifaceted competency in adapting and recovering from adversity, may mitigate the potential impact of adversity in search and buffer these negative effects of search to maintain psychological well-being (Prince-Embury, Saklofske, & Veseley, 2015). No research to the authors' knowledge has examined the associations between meaning in life, resiliency, and satisfaction with life, as a component of subjective well-being. Thus, this study provides a unique contribution of the dispositional correlates of meaning in life that may have an impact on the resiliency and satisfaction with life association.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data were collected from a sample of 289 undergraduate students (78.2 % females) between the ages of 17 to 25 years (M = 17.94, SD = 0.81) from a large university located in central Canada. Participants were recruited from the Department of Psychology's subject pool and upon signing up for the study, participants were directed to an online survey. Participants completed a battery of questionnaires online using the web-based survey tool Qualtrics. Upon completion of the study, participants were debriefed. As compensation, participants were awarded one credit towards an introductory psychology course. The study was approved by the university's institutional ethical review board.

Measures

Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ; Steger et al., 2006). The MLQ is a 10-item self-report measure that assesses the extent to which the individual is searching for meaning in life and the presence of meaning in life that the individual experiences. The statements are rated using a 7- point Likert scale from 1 (absolutely untrue) to 7 (absolutely true). Evidence of construct validity, test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and convergent and discriminant validity of the MLQ were established in previous studies (Steger et al., 2006; Steger & Kashdan, 2007).

Resiliency Scale for Young Adults (RSYA; Prince-Embury, Saklofske, & Nordstokke, 2017; Wilson et al., 2017). The RYSA is comprised of 50 items that measures three factors of personal resiliency, including sense of mastery, sense of relatedness, and emotional reactivity (Prince-Embury, 2006, 2007; Prince-Embury & Saklofske, 2013) on a 5-point scale 0 (never) to 4 (almost always). Sense of mastery is defined as an individual's sense of competence (i.e., belief in one's capabilities), self-efficacy (i.e., belief that one can master their environment), and adaptability (i.e., ability to adjust oneself and behaviour when needed; Prince-Embury & Saklofske, 2014; Prince-Embury et al., 2017). Sense of relatedness is defined as perceived access to social support, trust, comfort, and tolerance of others (Prince-Embury & Saklofske, 2014). Emotional reactivity, defined as the frequency and intensity of maladaptive emotional responses when confronted with adversity, represents a vulnerability factor to resiliency (Prince-Embury et al., 2017). Given that emotional reactivity represents a vulnerability factor and this study is primarily concerned with the protective factors of resiliency, only the two protective factors (i.e., sense of relatedness and sense of mastery) were included as predictors. Previous research has supported construct validity of the factor structure, reliability, and concurrent validity with related psychological concepts (Prince-Embury et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2017).

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). The SWLS (Lucas, Diener, & Suh, 1996) was designed to measure the cognitive aspects of subjective well-being using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The SWLS has demonstrated strong reliability and evidence of validity (for a review, see Pavot & Diener, 1993).

Statistical Analysis

To illustrate effects of moderating variables on each individual resiliency factor, two sets of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted for each of the two resiliency factors (i.e., sense of mastery, sense of relatedness) with satisfaction with life (SWL) as the criterion variable. The predictor and moderator variables were centered around the mean scores in this analysis to avoid multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991; Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). In the first hierarchical regression analysis, a regression model (block 1) predicting the outcome variable SWL from both the predictor (i.e., sense of mastery) and the moderator variables (i.e., presence of meaning, search for meaning) was conducted. Next, an interaction effect to the previous model (block 2), with two interaction terms created between sense of mastery and the predictors (sense of mastery × presence of meaning; sense of mastery × search for meaning) was further examined. This analysis was repeated for the second hierarchical regression analysis with sense of relatedness as the predictor and SWL as the outcome. All analyses were conducted on SPSS version 22 and Process version 2.16.3, a versatile modeling tool that integrates with SPSS to provide moderation analyses (Hayes, 2016).

Results

Descriptive statistics, Cronbach's alpha, and zero-order correlations of the study variables were computed in Table 1. Independent samples t-tests and regression analyses on gender and age, respectively, were conducted and these variables did not significantly predict SWL in this sample. Therefore, age and gender were not included as covariates in this model. Bivariate correlations show satisfaction with life was positively associated with presence, sense of mastery, and sense of relatedness.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations of the study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Search | .90 | ||||

| 2. Presence | -.03 | .90 | |||

| 3. Satisfaction | -.05 | .58** | .88 | ||

| 4. Mastery | .08 | .53** | .57** | .89 | |

| 5. Relatedness | -.05 | .47** | .56** | .68** | .90 |

| Mean | 25.15 | 22.21 | 24.06 | 41.13 | 55.16 |

| SD | 6.38 | 6.92 | 6.60 | 8.12 | 10.47 |

Note.N = 289. Search = Search for Meaning subscale in Meaning in Life Questionnaire; Presence = Presence of Meaning subscale in Meaning in Life Questionnaire; Satisfaction = Satisfaction with Life Scale; Mastery = Mastery Factor of Resiliency Scale for Young Adults (RYSA); Relatedness = Relatedness Factor of RYSA; Cronbach alphas in diagonal are in italics.

**p <.001.

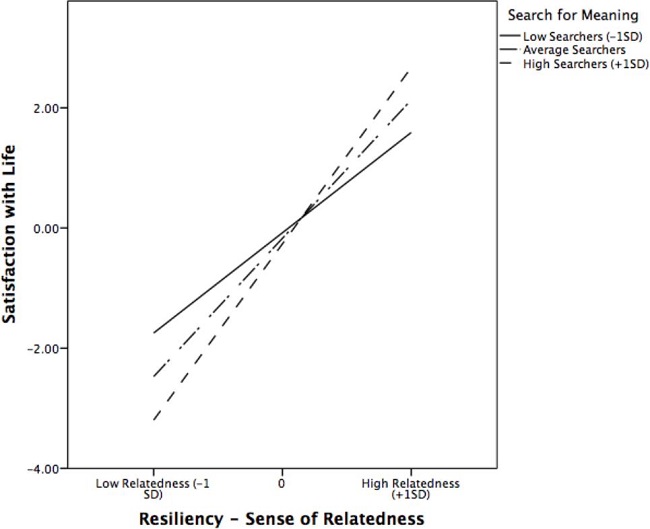

Table 2 includes results of the hierarchical regression analysis with sense of mastery, presence of meaning in life, and search for meaning predicting SWL. In step 1 of the hierarchical regression analysis, sense of mastery, presence, and search accounted for 44.1% of the variance in SWL, F(3, 285) = 74.87, p < .001. In step 2, the interaction effect of sense of mastery × search for meaning accounted for an additional 1.4 % of the variance in SWL, F(5, 283) = 47.17, p < .001. This interaction term significantly contributed to the variance of SWL (B =.01, β =.11, p < .05) and was probed through testing the conditional effects of resiliency at three levels of search for meaning (i.e., one standard deviation below the mean, at the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean; West, Aiken, & Krull, 1996). Simple slopes analyses revealed that the association between resiliency and SWL was stronger at higher levels of search (b =.36) than at average levels (b = .29) and at lower levels of search (b = .22). Figure 1 illustrates the simple regression slopes at three levels of search for meaning with sense of mastery and satisfaction with life as the predictor and outcome, respectively.

Table 2. Results of hierarchical regression analysis for search, presence, and sense of mastery predicting satisfaction with life.

| Variable | B | SE of B | β | ∆R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Sense of Mastery | .31 | .04 | .38** | .44 |

| Presence of Meaning | .36 | .05 | .38** | ||

| Search for Meaning | -.07 | .05 | -.07 | ||

| Step 2 | Sense of Mastery x Presence | .01 | .01 | .05 | .01 |

| Mastery x Search | .01 | .01 | .11* |

Note.N = 289.

*p < .05,

**p < .001, Mastery = Mastery Factor of Resiliency Scale for Young Adults

Figure 1. The interaction effects of search for meaning in life and sense of mastery on satisfaction with life, with search for meaning as a moderator.

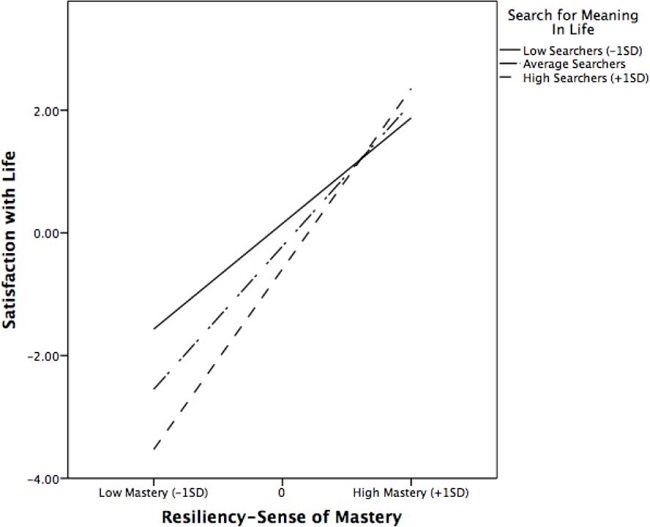

A second hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to investigate the moderating effects of meaning in life in the positive association between sense of relatedness and satisfaction with life. In step 1 of a hierarchical regression analysis, sense of relatedness, presence, and search accounted for 44.6 % of the variance in SWL, F(3,285) = 76.46, p < .001. In step 2, the interaction effect of relatedness × search accounted for an additional 1.5 % of the variance in SWL, F(5, 283) = 48.46, p < .001. This interaction term significantly contributed to the variance of SWL (B =.01, β =.11, p < .05). The summary of the results of the hierarchical regression analysis for search for meaning and sense of relatedness in predicting satisfaction with life were presented in Table 3. Simple slopes analyses revealed that relatedness was positively associated with satisfaction with life at both lower and higher levels of the search for meaning. However, the association was stronger at higher levels of search for meaning (b = .28) compared to average (b = .22) and lower levels (b =.16) of search for meaning. Figure 2 illustrates the simple regression slopes at three levels of search for meaning with sense of relatedness and satisfaction with life as the predictor and outcome, respectively.

Table 3. Results of hierarchical regression analysis for search, presence, and sense of relatedness predicting satisfaction with life.

| Variable | B | SE of B | β | ∆R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Search | -.02 | .05 | -.01 | .45 |

| Step 2 | Presence | .39 | .05 | .41** | |

| Relatedness | .23 | .03 | .37** | ||

| Relatedness x Presence | .01 | .<.01 | .07 | .01 | |

| Relatedness x Search | .01 | .<.01 | .11* |

Note.N = 289.

*Significant at p < 0.05,

**Significant at p < 0.001, Relatedness = Relatedness Factor of RYSA

Discussion

Although previous studies showed that individuals who are searching for meaning report a lesser sense of well-being compared to others who are not searching for meaning (e.g., Steger et al., 2006), this study showed that individual differences in protective facets of resiliency may change this association. The present study found that search for meaning had a significant moderating effect between the two protective facets of resiliency (i.e., sense of mastery, sense of relatedness) and satisfaction with life (SWL). More specifically, in the first hierarchical regression model, sense of mastery was positively associated with SWL at all levels of search for meaning. However, this positive association between sense of mastery and SWL were stronger at higher levels compared to lower levels of search for meaning. These results would suggest that individuals high in search for meaning with high levels of mastery have the greatest SWL, while individuals high in searching for meaning with low mastery have the lowest SWL. Sense of mastery involves an optimistic view of oneself as well as the future, and the belief that one has the capabilities to thrive and master their own environment (Prince-Embury et al., 2016). Individuals with high sense of mastery who engage in search for meaning may search in an open or approach-oriented fashion, allowing them to achieve aspirations and insights to experience greater psychological well-being (Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan, & Lorentz, 2008). In contrast, for individuals with a negative, deficit-based approach, previous researchers have hypothesized search for meaning amongst those individuals may accompany existential frustration (Baumeister, 1991; Klinger, 1998). Ultimately, search for meaning under positive conditions through sense of mastery could act as an opportunity to discover new avenues, challenges, and desires towards fulfillment in life.

Aligned with previous research, Shin and Steger (2016) found that when students perceived their college environments to be supportive, search for meaning was positively associated with presence of meaning. The authors concluded that perceived support may have promoted students'presence of meaning through protection against the negative effects associated with searching for meaning. Similarly, the present study found that sense of relatedness had a positive association with satisfaction with life. This positive association between sense of relatedness and SWL was stronger at higher levels compared to lower levels of search for meaning. Sense of relatedness is conceptualized as a sense of trust and perceived access to support, as well as comfort and tolerance with others (Prince-Embury et al., 2017). Hence, the construct is proposed to be a major underlying mechanism in the formation and maintenance of relationships as the basis of developing a support system (Prince-Embury, 2006, 2007, 2013, 2014). Overall, individuals with high sense of relatedness may be more socially adept and have a stronger social network that could promote a healthier approach to search for meaning.

This study is not without its limitations that will require further research. First, the present study utilized a crosssectional design rather than a longitudinal design and temporal associations between study variables were not able to be determined. Second, this study uses self-report measures and, like all studies involving self-report questionnaires, is limited to the observations and insights of the individual. Proper insight into the present study variables can only be determined by self-report and these factors may be associated with biases. Future studies should assess whether self-report ratings of meaning in life and resiliency are associated with social desirability biases. Third, it should be noted that the sample in this study involves undergraduate students from one institution in a large Canadian University and further, there was an imbalance in the ratio and number of females and males. Future studies should examine the generalizability of these findings with more diverse populations, especially given that previous research found that younger adults report searching for meaning to a greater extent than older adults (Bodner, Bergman, & Cohen-Fridel, 2014). Moreover, the negative association between searching for meaning and presence of meaning is stronger for older adults than for younger adults (Steger, Oishi, & Kashdan, 2009). These findings suggest that searching for meaning may be particularly disadvantageous to older adults compared to their younger counterparts. Future research should investigate whether the present findings may be replicated in an older population.

Overall, these results suggest that resiliency, as measured by two protective factors of sense of mastery and sense of relatedness, may be an asset for those who are seeking meaning in predicting greater psychological well-being. The present study suggests that although the literature shows search for meaning is associated with psychosocial distress, higher educational settings should provide social support and build up an individual's sense of mastery while reassuring these individuals that the search of meaning is part of a developmental process (Shin & Steger, 2016). Through efforts directed towards enhancing resiliency, individuals searching for meaning could gain new insights and ultimately achieve satisfaction with life. Thus, the importance of enhancing resiliency should be brought to the forefront to researchers and student affairs professionals. These findings provide new insight into the relationship between resiliency, meaning in life, and well-being that hopefully will advance a coherent and multifaceted theoretical framework of the pathways in which well-being may be achieved.