My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Enfermería Global

On-line version ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.19 n.59 Murcia Jul. 2020 Epub Aug 10, 2020

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.380041

Reviews

Educational interventions on nutrition and physical activity in Primary Education children: A systematic review

1 Master Universitario en Investigación en Ciencias Sociosanitarias. Enfermera en Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (HUCA). Asturias. España. marinallosav@gmail.com

2 Departamento de Enfermería y Fisioterapia. Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud. Universidad de León. España

3 Grupo de Investigación SALBIS. Universidad de León. España

4Grupo de Investigación Enfermería y Cultura de los Cuidados. Universidad de Alicante. España

Introduction:

Educational interventions in the school environment seem the most effective way to act against childhood obesity. The objectives of this systematic review were to describe the educational interventions on nutrition and / or physical activity carried out in primary school students in order to reduce or prevent childhood obesity and analyze the effectiveness of these interventions.

Methodology:

A bibliographic search was carried out in the WOS and SCOPUS databases. Eligibility criteria were established based on the acronym PICOS: (P) primary school children (6-12 years), (I) studies that will carry out nutrition and / or physical activity interventions in the school setting, (C) not receive any intervention, (O) evaluate the effect of educational programs on childhood obesity, (S) experimental studies, published between 2013 and 2017.

Results and discussion:

571 articles were identified, and finally 22 studies were included. It was found that the most promising interventions were the combined ones. Duration, parental involvement, gender and socioeconomic status can influence the effectiveness of interventions. A shortage of theoretically based interventions was observed.

Conclusions:

The interventions with the best results are the combined ones, with activities included in the curriculum and the participation of the parents. Long-term interventions seem to have better results. These programs help the acquisition of healthy habits and there is some evidence that they are useful in decreasing the Body Mass Index (BMI) or in the prevention of childhood obesity.

Key words: physical activity; education for health; primary education; nutrition; childhood obesity; prevention

INTRODUCTION

We can consider the obesity as a complex and multifactorial chronical disease. Its development is influenced by genetic, environmental and behavioral factors. Among of them, we can highlight several environmental and behavioral factors as feeding habits, the lack of physical activity and sedentary lifestyle1.

Both the overweight and obesity in children have a great influence in the development of different physical comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus type-II, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, osteoarticular disorders or different types of cancer. Moreover, these ill children are also exposed to other psychosocial consequences like low self-esteem, body image disorders, depression, stigmatization, margination or bulling1.

In the las three decades the childhood obesity has been doubled worldwide. In 1980 the obesity rate in children between 6-11 years old was around 7%, increasing till 18% in 20101.

According to a US study which analyzed the tendency of the prevalence of obesity in children and teenager between 2013 and 2014, the 17% of the children between 2 and 19 years old were suffering obesity and the 5.8% extreme obesity. In 1990 the obesity in children between 6 and 11 years old was about 11.3% numbers that raised up to 19.6% in 2008 and keeping constant till 20142.

In Spain, the ALADINO study carried out in 2015 and which analyzed the overweight and obesity among children ion the in the primary school showed that the overweight rate in children between 6 and 9 years old was 23.2% (22.4% in boys and 23.9% in girls) while the obesity reached 18.1% (20.4% in boys and 15.8 in girls)3.

Aranceta Bartrina et al.4) proposed that the educational actions for health focused on children in the primary school (6-12 years old) are the most effective way to act against the increase of childhood obesity. It seems that these are educational strategies are useful in the prevention and modification of unhealthy habits which favor the weight overload.

The primary school is one of the most adequate place for carrying out these type of educational actions since the children spend a lot of hours there and, moreover, it is possible to reach almost all the population in short period of time5.

On the other hand, the period in the primary school is an ideal frame for these type of actions because the most susceptible age to change in habits and behavior5. It also quite clear that the overweight and obesity became permanent between 11 and 12 years old meaning that the risk of suffering obesity and comorbidities as an adult is much higher. this fact justifies the need of educational actions in children below 12 years old in order to avoid a weight overload at young age6.

A recent meta-analysis concluded that the actions on the diet and the physical activity performed in primary schools are very useful in the prevention of the overweight7. However, other authors claimed that the actions on the feeding and physical exercise during the school period are not effective in the prevention of childhood obesity and, if some positive effects are achieved, these are not kept in time. There is also no agreement about the ideal extension of the education programs to achieve long-lived changes in the children weight8.

For all these reasons and due to the high prevalence of the childhood obesity and the associated health risks, the following research question is posed following the PICOS format (Patient/Problem, Intervention, Control/Comparison, Results, Design of studies): Are the educational actions on nutrition and/or physical activity carried out on primary schools (6-12 years old) effective for the prevention and/or decrease the childhood obesity?

- P: children on primary school (6-12 years old)

- I: educational actions in primary schools about nutrition and/or physical activity

- C: no interventions or education about nutrition and/or physical activity is given

- O: effect on the weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference or skin folds (obesity measurements)

- S: experimental studios on control groups

On this way, an extensive bibliographic review is carried out to:

- Describe the educational actions on feeding habits and/or physical activity carried out in children on primary school in order to reduce or prevent the childhood obesity

- Analyze the efficiency of this interventions.

METHODOLOGY

Protocol

A systematic bibliography review was carried out following the guidelines established in PRISMA 2010 statement for systematic reviews and meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria

Studies about children in the primary school period (6-12 years old) were included in this review.

The experimental studies with control groups in which nutritional and/or physical activity interventions have been carried out in the schools against no interventions or only the typical education about feeding and physical activity.The studies carried out with actions out of the school environment (the community, at home or primary attention) or without any control group have been avoided.

Studies whose objectives were the evaluation of the impact of nutrition and/or physical activity intervention programs on the childhood obesity with an analysis. The reports that did not include this information were avoided.

Other eligibility criteria were the date and language. Only studies published in the las 5 years (January 2013 - September 2017) in Spanish or English were considered. The occupation of the authors of the study or the amount of time employed in the study were not taken into consideration.

Information and searching sources

The electronic databases used for the bibliographic search were Web of Science (WOS) y SCOPUS. These databases were employed from July 2017 till September 2017.

The search of articles was carried out using the following combination of terms and Booleansoperators both in WOS and SCOPUS: ("pediatricobesity" OR "obesity" AND ("healtheducation" OR "prevention" OR "intervention") AND ("schools" OR "educationprimary" OR "primaryschool") AND ("nutrition") AND("physicalactivity").

The employed filters in both databases were the date and type of document (2013 - 2017 and article or review, respectively).

Moreover, the references included in these studies were revised and incorporated if the eligibility criteria were fulfilled and they have not been found previously with the systematic search.

Selection of the studies

After the search, the duplicated studies were removed using the tools provided by Mendeley Desktop. Then, a deep analysis of the titles and abstracts was carried out to discard the irrelevant articles. The abstracts that were ambiguous about the eligibility criteria were selected to a more in detail review by a complete reading. These documents were then read and included if they fulfilled the eligibility criteria.

The quality of the methodology employed in the different studies were examined by a detailed read of the documents that satisfied the eligibility criteria. This was made by the use of CASPe, specifically: "11 preguntas para darsentido a un ensayoclínico"9.

Finally, a fine screening was carried out considering different evidence levels according to the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). The studies with evidence level SIGN "1-" y "2-" were removed since this tool does not recommend to use this type of studies due to their bias high potential.

Data Acquisition Process

The acquisition of the data from the articles that fulfilled the eligibility criteria and included in the final review, was carried out preparing twodifferent Tables (Table 1 y 2).In these Tables, the following data is summarized: year and reference, country, design of the study, sample, type of actuation, and main results and conclusions. Also the evidence degree according to SIGN scale was also included.

List of data

The main data extracted from each article for the preparation of this work were: the age of the children, information about nutrition and/or physical activity interventions, related to school, parent's participation, duration of the interventions and duration of the results.

RESULTS

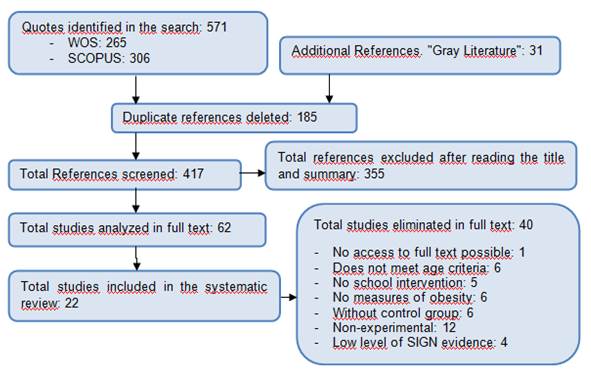

After the systematic bibliographic search in the databases, a total of 571 articles were found. First, 185 articles were removed since they were duplicated. Then, another 355 irrelevant articles were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts. After this first selection, 62 articles were identified as potentially relevant. After analyzing the full content of 61 of these articles, finally only 22 articles were considered for the systematic review (Figure 1).

Among the selected 22 articles, 19 of them were randomized experimental studies6)(10)(11)(12)(13)(14)(15)(16)(17)(18)(19)(20)(21)(22)(23)(24)(25)(26)(27, 1 of them was a non-randomized experimental study with control group28and 2 of them werequasi-experimental studies with control group29)(30, as it summarized in Table 1 together with the evidence level SIGN assigned to each one.

Table 1. Information of the included articles.

| Reference | Country | Design of the study | EvidenceSIGN |

|---|---|---|---|

| de Greeff et al. (2016)10 | Holland | Randomized controlled trial | 1++ |

| Fairclough et al. (2013)11 | England | Randomized clinical trial | 1++ |

| Friedrich et al. (2015)12 | Brazil | Randomized controlled clinical trial | 1++ |

| Grydeland et al. (2014)13 | Norway | Randomized controlled trial | 1++ |

| Kain et al. (2014)14 | Chile | Randomized clinical trial | 1++ |

| Kipping et al. (2014)6 | England | Randomized controlled trial | 1++ |

| Kocken et al. (2016)15 | Holland | Randomized controlled trial | 1++ |

| Meng et al. (2013)16 | China | Randomized controlled clinical trial | 1++ |

| Sacchetti et al. (2013)17 | Italy | Randomized Experimental | 1++ |

| Siegrist et al. (2013)18 | Germany | Randomized Experimental | 1++ |

| Tarro et al. (2014)19 | Spain | Randomized controlled trial | 1++ |

| Waters et al. (2017)20 | Australia | Randomized group trial | 1++ |

| Wright et al. (2014)21 | EEUU | Randomized controlled trial | 1++ |

| Xu et al. (2015)22 | China | Randomized controlled trial | 1++ |

| Bere et al. (2014)26 | Norway | Randomized trial | 1+ |

| Habib-Mourad et al. (2014)25 | Lebanon | Randomized controlled trial | 1+ |

| Meyer et al. (2014)27 | Brazil | Randomized controlled trial | 1+ |

| Quizán-Plata et al. (2014)23 | Mexico | Randomized controlled trial | 1+ |

| Wang et al. (2015)28 | China | Non-randomized controlled trial | 1+ |

| Llargues et al. (2017)24 | Spain | Randomized experimental longitudinal study | 2++ |

| Klakk et al. (2013)29 | Denmark | Quasi-experimental longitudinal | 2+ |

| Vanelli et al. (2014)30 | Italy | Quasi-experimental | 2+ |

In all the selected articles, the population under study was 6-12 years old children in the primary school. Two of the studies only evaluated actions on nutrition26)(30, five of them only on physical activity10,17,18,27,29and fifteen of them evaluated combined actions on nutrition and physical activity6)(11)(12)(13)(14)(15)(16)(19)(20)(21)(22)(23)(24)(25)(28. These data were summarized in Table 2 together with the rest of the extracted information.

Table 2. Data from the experimental studies

| Reference | Sample | Interventions | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Greeff et al. (2016)10 | 388 (2nd-3rd course) | -Project: ‘‘Fit in Vaardig op school'', integrates PA* into routine classes. -Duration: 22 weeks | -No differences in BMI in the group under intervention. -Remarkable increase of BMI in control group. -No differences in physical condition. | -The duration and intensity of the intervention is not clear. |

| Fairclough et al. (2013)11 | 318 (10-11 years old) | -Program: GetEducated! (CHANGE!) -PA + HD intervention† -Curriculum. -Participation of parents. -Duration: 10 weeks | -Decrease waist circumference and BMI. -Increase of the PA. -Better nutritional results at a higher socioeconomic level. -10 weeks post-intervention: changes are maintained. | -More effective in girls and high socioeconomic status. - Greater effectiveness of combined interventions, included in the curriculum and with parental involvement. |

| Friedrich et al. (2015)12 | 600 (1st-4th course) | -TriAtivaProgram: education, nutrition and physical activity. -PA and HD intervention. -Curricular and extracurricular -Participation of parents. -Duration: 1 year. | -Significant decrease in BMI. -Reduction of excess weight and obesity | -The program produces positive effects in the reduction of BMI and changes in the prevalence and decrease of obesity. |

| Grydeland et al. (2014)13 | -1324 (6th course) | -HEIA study. -Multiple intervention: HD + PA -Curricular and extracurricular. -Participation of parents. -Duration: 20 months.. | -No effects on weight. - Female gender lower BMI increase. - Beneficial effect on BMI of children of parents with higher education. | -Gender and socioeconomic level must be taken into account in the design of interventions. |

| Kain et al. (2014)14 | -1471 (6-8 years old) | -Intervention: HD + PA -Included in the curriculum. -Participation parents. -Duration: 1 year. | -Percentage increase of healthy foods that were brought to school and increase PA. -The BMI decreased or remained sTable. -The prevalence of obesity without changes. | -The Intervention controls obesity, but does not prevent it. -The changes are not expected to be maintained in the long term. -More effective intervention in girls than in boys. |

| Kipping et al. (2014)6 | -2221 (8-11 years old) | - AFLY5 intervention, school-based (curriculum). -Intervention: PA and consumption of fruits and vegeTables. -Participation of parents. -Duration: 5 years. | -Decrease of sedentary lifestyle and consumption of unhealthy drinks and snacks. -No improvement in PA, consumption of fruits and vegeTables, or BMI is observed. | -It is unlikely that simple interventions at the school level will be effective. |

| Kocken et al. (2016)15 | -863 (9-11 years old) | -Extra Fit Fit! -Intervention: PA + HD -Curriculum -Participation of parents. -Duration: 2 years. | -There are no differences in the consumption of sugary fruits and drinks, in the increase in PA, or in the BMI. -Increase of PA and nutrition knowledge. | -It is important to invest more in parental involvement. |

| Meng et al. (2013)16 | -8301 (6-12 years old) | -Intervention: HD + PA. -Participation of parents. -Duration: 1 year. | -BMI reduction (PA + HD intervention) -The reduction in prevalence of overweight / obesity does not have statistical significance. -No BMI reduction of PA / HD separated interventions is observed. | -Useful interventions to improve BMI, and effect on obesity prevalence. -Efficient short-term intervention is not guaranteed to remain long term. |

| Sacchetti et al. (2013)17 | 497 (3rd course) . | -Intervention: PA -Curriculum -Duration: 2 years | -At 2 years, increase in PA, decrease in sedentary lifestyle. -Improvement in physical attitude tests. -Decreased prevalence of overweight / obesity. | -A school-based PA intervention is effective in causing changes in daily PA habits. |

| Siegrist et al. (2013)18 | 826 (2nd-3rdcourse) | -JuvenTUM intervention -Intervention: PA -Participation of parents -Duration: 1 year. | -Reduction of the waist circumference. - Increase in PA, one year after post-intervention without differences. -Improvement of physical fitness. | - Interventions that include parents and changes in the school environment increase FA. |

| Tarro et al. (2014)19 | 1939 (7-11 años) | -EdAl Program: Food Education. -Participation of parents. -Duration: 28 months. | -The prevalence of obesity decreased. -No differences from BMI at 28 months. -Improvement of eating habits and PA. | -Long term intervention is effective to reduce obesity prevalence - Better results in boys than in girls. -Schools are ideal places. |

| Waters et al. (2017)20 | 3222 children | -Functional program healthy in Moreland! -Intervention: PA + HD. -Duration: 3.5 years. | -There are no differences in BMI, weight, waist circumference or the proportion of overweight / obesity. -Increase of the consumption of fruit / vegeTables, and decrease of the consumption of sugary drinks. -There are no changes in PA. | -It is possible to achieve improvements in feeding habits from school. With long-term objectives the results could be improved much more. |

| Wright et al. (2014)21 | 251 (8-12 years old) | - Kids N Fitness project. -Intervention: PA + HD -Curriculum -Participation of parents -Total duration: 1 year | - Decrease in BMI at 4 months. The results were maintained after a year. -PA increase. -Decrease of sedentary lifestyle (television time). | -The interventions are fundamental, but they must be reinforced with school policies. |

| Xu et al. (2015)22 | 1182 (4th course) | -CLICK-Obesity program. -Intervention: PA + HD -Curriculum. -Participation of the family. -Duration: 1 year. | -There are no differences in BMI or obesity prevalence. - Increase in PA and decrease sedentary lifestyle. | -In order for interventions on obesity to succeed, it is important the support from the school (best scenario) and the family participation. |

| Bere et al. (2014)26 | 1950 (10-12 years old) | -Norwegian School Fruit Program intervention -Intervention: Distribute free fruit at school. -Duration: 1 year. | -Post-intervention: increased intake of fruits / vegeTables and reduced consumption of unhealthy snacks. -3 years post-intervention: no weight differences and in BMI. -7 years post-intervention: significant difference in the prevalence of overweight. | -Giving free fruit at school seems to contribute to the prevention of weight gain in children. -Effective intervention to change eating habits. -The long-term studies are important. |

| Habib-Mourad et al. (2014)25 | 387 (9-11 years old) | -Health-E-PALS program. -Intervention: HD + PA. -Curriculum. -Participation of parents. -Duration: 3 months | -Increased breakfast habit. -Increase of knowledge about HD and PA. -No changes in the BMI. | -Increased of knowledge about healthy habits, but not reflected in the BMI. -Participation of parents, fundamental. |

| Meyer et al. (2014)27 | 289 children | -KISS project. -Intervention: PA -Duration: 9 months. | -Decreased body fat. However, 3 years later, the result is not maintained. -3 years later: intervention group maintain higher PA levels. | -Three years after the intervention, the initial beneficial effects were only observed for aerobic fitness. |

| Quizán-Plata et al. (2014)23 | 126 (6-8 years old) | -Intervention: PA + HD -Participation of parents. -Duration: 9 months. | -There are no significant differences in BMI. -Increase in fruit consumption and decrease in fat consumption. -Increased knowledge about healthy diet. -Increased PA. | -The interventions on HD and PA are effective in promoting healthy lifestyles and even more effective with parental involvement. |

| Wang et al. (2015)28 | 438 (7-11 years old) | -Intervention: PA + HD. -Curriculum -Participation of parents. -Duration: 1 year. | -Improvement in nutrition and increase in PA. -No differences in BMI. -Reduction of body fat percentage. -Decreased blood pressure. | -Integral intervention is more useful in reducing BMI than interventions in PA and HD separately. |

| Llargues et al. (2017)24 | 509 children | -Avall project. -Interventions: HD + PA -Curriculum + extracurricular. -Participation of parents. -Duration: 2 years. | -Decrease of sedentary lifestyle. -4 years post-intervention: reduction of excess weight. -The greater the weight and the lower the level of study of the parents, the greater the increase in BMI. | -The intervention is effective in limiting the growing tendency to overweight. -The changes remained at least 4 years. |

| Klakk et al. (2013)29 | 1218 (2nd- 4th course) (8-12 years old) | -CHAMPS-DK study. -Intervention: PA -Curriculum -Participation of parents. -Duration: 2 years. | -Post-intervention: no results on BMI. -2 years post-intervention: significant effect on the prevalence of overweight / obesity. | -The intervention does not improve BMI or body fat percentage, but it does improve the prevalence of obesity and overweight. |

| Vanelli et al. (2014)30 | 632 (3rd-5thcourse (8-11 years old). | -GIOCAMPUS Program Campaign. -Intervention: HD -Participation of parents. -Duration: 3 years. | -Increase breakfast consumption. -More consumption of fruits. -No differences in BMI. -No changes in obesity. | -The participation of the family is important. -The intervention is effective in promoting breakfast. |

*PA=Physical Activity

†HD=Healthy Diet.

DISCUSSION

Nutrition interventions

It has been found that the activity of distributing free fruits in the schools increases its consumption while reduces the consumption of unhealthy snacks and helps to decrease the prevalence of the obesity. Therefore, this activity is a clear strategy to prevent overweight and improve eating habits26.

On the other hand, it was observed that the interventions focused on stimulate a good breakfast help to improve the healthy eating habits but do not show any effect on the BMI of the children30.

Physical activity interventions

The strategy of increase the physical activity in the curriculum seems to have positive effects since the practice of exercise is increased and the physical attitude improved17)(18 while also, the waist circumference is reduced18. However, one study in which this intervention was used found no improvement in the physical condition of the children nor any effect in the obesity measurements10.

It was also observed that this type of intervention produces long term results since even 2 years after its completion, it was found a decrease in the body fat and overweight and obesity prevalence,having these children less risk of becoming obese17,29. However, in another study in which at the end of the intervention it was possible to reduce fat, improve physical attitude and an increase in exercise, years later only the effects on the increase in activity were maintained27.

Combined interventions: nutrition and physical activity

Among the fifteen studies that performed combined interventions6)(11)(12)(13)(14)(15)(16)(19)(20)(21)(22)(23)(24)(25)(28, nine obtained positive results in the decrease or maintenance of BMI11)(12)(13)(14)(16)(19)(21)(24)(28and sixdid not achieve statistically positive changes on children's BMI6)(15)(20)(22)(23)(25.

Programs with educational interventions of physical activity and healthy eating, either included in the curriculum or extracurricular, achieved a decrease in waist circumference and BMI. In addition, physical activity was increased and eating habits were improved, with a decrease in the prevalence of obesity11)(12)(19)(21.

Comparing the combined interventions with the simple ones, it was observed that the first ones were more useful to increase activity, improve diet and decrease body fat28. It was also found that comprehensive programs achieve, years after their completion, a significant reduction in the excess of weight24.

On the other hand, one study found that these types of interventions do not always reduce the prevalence of obesity, being these programs useful to control it but not to prevent it14. Additionally, it cannot be guaranteed that the reductions in the BMI are maintained in the long term16.

In contrast with these results, there are other studies that failed to reduce BMI6)(15)(20)(22)(23)(25. Although it is also true that in some cases they did reduce sedentary lifestyle, the consumption of sugary drinks and unhealthy snacks and increase the consumption of fruits and vegeTables and physical exercise6)(20)(22)(23.

Another remarkable about this type of interventions was the significant increase in knowledge about healthy eating and physical activity that children showed15)(23)(25.

Parental involvement in educational programs

There are many studies that have included the participation of parents/caregivers in the educational interventions6)(11)(12)(13)(14)(16)(19)(21)(22)(23)(24)(25)(28)(29)(30.

Fairclough et al.11explained that the interventions that were most effective were those combined, those included in the curriculum and those with parental involvement. This conclusion was also reached by other authors who proposed that, for obesity interventions to be successful, school support and family participation are important, since parents are essential for the success of these interventions23)(25)(30.

A study that did not achieve changes in obesity measures, proposes that it is important to invest more in parental involvement to achieve better results15.

Sex and socioeconomic level

Three experimental studies found that girls had better results in lowering BMI than boys11,13,14.Only one study found better results in boys than girls19.

The socioeconomic level also seems to influence the results of the programs. It was found that the higher the socioeconomic and educational level of the parents is, the better the results on the BMI of the children are11)(13. Another study observed that the lower the educational level of the parents is, the greater the increase in BMI is24.

Thus, it seems that both gender and socioeconomic status must be taken into account in the design of educational interventions that attempt to influence the weight of children13.

Duration of the interventions

The results in this aspect are quite heterogeneous. The duration of the interventions is an important aspect, although it is not clear what the ideal duration is8.

The duration of the experimental studies included in this review varies from 10 weeks to 5 years, being the average duration between 1 and 2 years.

Two studies with a duration of one year that obtained positive results on obesity, did not guarantee that the effects were maintained in the long term14)(16. A 28-month intervention that was also effective at the end of the study, failed to subsequently maintain the effects achieved on BMI19.

However, studies that lasted 2 years, achieved positive effects with their interventions and / or that the effects were maintained over time15)(17)(24)(29.

Theories on which the studies are based

Among all the studies included in this review only six mentioned the use of some theory6,11,15,20,25,28, although all included interventions with behavioral components.

The most common was the theory of social cognitive behavior, used by four authors6,11,25,28. Another one used the theory of planned behavior15and other one the health promotion theory20.

In this review, it was observed that of the four studies using the psychological theory of behavior change, only two achieved positive results11)(28.Studies based on other theories did not obtain significant results15)(20.

Summary of the results

This systematic review has concluded that educational interventions on nutrition and / or physical activity carried out in primary schools seem to have a positive effect on eating habits and physical activity. The consumption of fruits and vegeTables increased, decreasing the consumption of sugary drinks and unhealthy snacks. The practice of physical also increased exercise and the physical attitude of children improved. However, not all studies included in this work have positive effects on BMI.

Although it was observed that the combined interventions on nutrition and physical activity seem to be more promising in the treatment and prevention of childhood obesity11)(12)(13)(14)(16)(19)(21)(24)(28, it was also found that some studies of a single component, either interventions only on nutrition or only on physical activity, have also a positive effect on the treatment or prevention of weight overload17)(18)(26)(29.

Regarding the duration of the interventions, it seems clear that it is an important aspect of their effectiveness and that those that extend longer in time obtain better results10)(17. However, it is not clear what is the ideal duration for a program to be successful, nor what interventions are considered in the long term5)(8. In this review it was found that programs with a duration of one year mostly achieve positive results and those with a duration of 2 or more years can mantain these positive effects over time14)(15)(17)(19)(24)(29.

Parental involvement in educational interventions is essential in obtaining good results11)(15)(18)(22)(23)(25)(30. It is also important to take into account both sex and socioeconomic status of participants in educational programs, as it can influence the effectiveness of interventions8.

Most studies did not mention the theory on which they based their educational interventions. Despite this, it was found that the most used was the theory of social cognitive behavior, being the only one that achieved significant results on obesity11)(28.

Summary of the evidence

It was found that the combined interventions on nutrition and physical activity are the most used and effective on BMI. Moreover, they are mostly rated according to the SIGN scale, with high levels of evidence ("1 ++" and "1+"). On the other hand, among the interventions on only nutrition, it was observed that the strategy of distributing free fruit in schools improves eating habits and decrease the prevalence of overweight, being identified with a level of evidence "1+". Conversely, the intervention on increasing the number of breakfast was rated with a level of evidence "2+".

In general, programs on physical activity increase exercise practice, improve physical attitude and help prevent obesity. These studies are identified with levels of evidence similar to the combined interventions.

Parental involvement has been identified as positive, obtaining good results in most of the studies that counted on their participation and identified according to the SIGN scale with high levels of evidence.

It is important to keep in mind that in order to develop this type of interventions the socioeconomic and educational level of the participants as well as the duration are important aspects. Interventions with a duration of 1 to 2 years, get better results, and after 2 years they manage to keep them for longer. These studies were identified with a level of evidence according to SIGN of "1 ++", "2 ++" and "2+".

On the other hand, it was found that the theory of social cognitive behavior is the most used, being classified the studies that use it and obtain good results with the highest levels of evidence.

Limitations

Some limitations were detected during the work on this systematic review. First, the search and selection of articles was carried out by the first author, and supported by the rest of the researchers, so there may be a bias in the selection of studies. The possibility of publication bias also exists, since it is more likely that intervention studies that failed to have a positive effect have not been published.

On the other hand, limitations were also found on the evidence quantification. The studies are heterogeneous in terms of size and characteristics of the sample and characteristics and duration of interventions. "Unclear risk" of bias was also found in most of the included studies when evaluating the quality of the articles, mainly due to lack of information on randomization, blinding and losses during follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

The initial proposed objectives were fulfilled:

- On the one hand, educational interventions on food and / or physical activity carried out in order to reduce or prevent childhood obesityin Primary School students have been described. It was concluded that the most used educational interventions in these last 5 years and which have achieved better results are the combined interventions on nutrition and physical activity, with activities included in the curriculum and the participation of parents. The optimal duration of interventions is not clear, although it can be concluded that long-term interventions seem to have better results.

- We have analyzed the effectiveness of these interventions and we could conclude that educational interventions on food and / or physical activity help to improve and acquire healthy habits: increasing the consumption of fruit and vegeTables, reducing the consumption of unhealthy snacks and sugary drinks, increasing the time devoted to physical activity and improving the physical attitude of children. There seems to be some evidences that they can also be useful in reducing children's BMI or preventing childhood obesity.

REFERENCIAS

1. Xu S, Xue Y. Pediatric obesity: Causes, symptoms, prevention and treatment. Exp Ther Med [Internet] 2016 [citado 25 de septiembre de 2017]; 11: 15-20. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26834850 [ Links ]

2. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Kit BK, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 Through 2013-2014. JAMA [Internet] 2016 [citado 27 de septiembre de 2017]; 315(21): 2292-9. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27272581 [ Links ]

3. Agencia Española de Consumo, Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. Estudio ALADINO 2015: Estudio de Vigilancia del Crecimiento, Alimentación, Actividad Física, Desarrollo Infantil y Obesidad en España 2015 [momografía en Internet]. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2016 [acceso 28 de septiembre de 2017]. Disponible en: http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/observatorio/Estudio_ALADINO_2015.pdf [ Links ]

4. Aranceta Bartrina J, Pérez Rodrigo C, Campos Amado J, Calderón Pascual V. Proyecto PERSEO: Diseño y metodología del estudio de evaluación. Rev Esp Nutr Comunitaria [Internet] 2013 [citado 19 de septiembre de 2017]; 19(2): 76-87. Disponible en: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84887122163&partnerID=40&md5=719efde2d5850532941f6aad81243bb2 [ Links ]

5. Hung LS, Tidwell DK, Hall ME, Lee ML, Briley CA, Hunt BP. A meta-analysis of school-based obesity prevention programs demonstrates limited efficacy of decreasing childhood obesity. Nutr Res. [Internet] 2015 [citado 30 de septiembre de 2017]; 35(3): 229-40. Disponible en: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0271531715000032 [ Links ]

6. Kipping RR, Howe LD, Jago R, Campbell R, Wells S, Chittleborough CR, et al. Effect of intervention aimed at increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviour, and increasing fruit and vegeTable consumption in children: active for Life Year 5 (AFLY5) school based cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ [Internet] 2014 [citado 29 de septiembre de 2017]; 348: g3256. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24865166 [ Links ]

7. Sobol-Goldberg S, Rabinowitz J, Gross R. School-based obesity prevention programs: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity[Internet] 2013 [citado 30 de septiembre de 2017]; 21(12): 2422-88. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23794226 [ Links ]

8. Amini M, Djazayery A, Majdzadeh R, Taghdisi M-H, Jazayeri S. Effect of School-based Interventions to Control Childhood Obesity: A Review of Reviews. Int J Prev Med [Internet] 2015 [citado 29 de septiembre de 2017]; 6: 68. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4542333/ [ Links ]

9. redcaspe.org, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Español [sede Web]. Alicante: redcaspe.org; 1998 [actualizada el 2 de febrero de 2016; acceso 8 de septiembre de 2017]. Disponible en: http://www.redcaspe.org [ Links ]

10. de Greeff JW, Hartman E, Mullender-Wijnsma MJ, Bosker RJ, Doolaard S, Visscher C. Effect of Physically Active Academic Lessons on Body Mass Index and Physical Fitness in Primary School Children. J Sch Health [Internet] 2016 [citado 21 de otubre de 2017]; 86(5): 346-52. DOI: 10.1111/josh.12384 [ Links ]

11. Fairclough SJ, Hackett AF, Davies IG, Gobbi R, Mackintosh KA, Warburton GL, et al. Promoting healthy weight in primary school children through physical activity and nutrition education: a pragmatic evaluation of the CHANGE! randomised intervention study. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2013 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 13: 626. Disponible en: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1471-2458-13-626?site=bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com [ Links ]

12. Friedrich RR, Caetano LC, Schiffner MD, Wagner MB, Schuch I. Design, randomization and methodology of the TriAtiva Program to reduce obesity in school children in Southern Brazil. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2015 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 15: 363. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25887113 [ Links ]

13. Grydeland M, Bjelland M, Anderssen SA, Klepp K-I, Bergh IH, Andersen LF, et al. Effects of a 20-month cluster randomised controlled school-based intervention trial on BMI of school-aged boys and girls: the HEIA study. Br J Sports Med [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 48(9): 768-73. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23624466 [ Links ]

14. Kain J, Concha F, Moreno L, Leyton B. School-based obesity prevention intervention in Chilean children: effective in controlling, but not reducing obesity. J Obes [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 2014: 8. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24872892 [ Links ]

15. Kocken PL, Scholten AM, Westhoff E, De Kok BPH, Taal EM, Goldbohm RA. Effects of a theory-based education program to prevent overweightness in primary school children. Nutrients [Internet] 2016 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 8(1): 12. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26742063 [ Links ]

16. Meng L, Xu H, Liu A, van Raaij J, Bemelmans W, Hu X, et al. The costs and cost-effectiveness of a school-based comprehensive intervention study on childhood obesity in China. PLoS One [Internet] 2013 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 8(10): e77971. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24205050 [ Links ]

17. Sacchetti R, Ceciliani A, Garulli A, Dallolio L, Beltrami P, Leoni E. Effects of a 2-Year School-Based Intervention of Enhanced Physical Education in the Primary School. J Sch Health [Internet] 2013 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 83(9): 639-46. DOI: 10.1111/josh.12076 [ Links ]

18. Siegrist M, Lammel C, Haller B, Christle J, Halle M. Effects of a physical education program on physical activity, fitness, and health in children: The JuvenTUM project. Scand J Med Sci Sport [Internet] 2013 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 23(3): 323-30. Disponible en: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84877650895&doi=10.1111%2Fj.1600-0838.2011.01387.x&partnerID=40&md5=acdf1b9ac688b0c2023b586fc1af6a32 [ Links ]

19. Tarro L, Llauradó E, Albaladejo R, Moriña D, Arija V, Solà R, et al. A primary-school-based study to reduce the prevalence of childhood obesity--the EdAl (Educació en Alimentació) study: a randomized controlled trial. Trials [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 15: 58. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24529258 [ Links ]

20. Waters E, Gibbs L, Tadic M, Ukoumunne OC, Magarey A, Okely AD, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a school-community child health promotion and obesity prevention intervention: Findings from the evaluation of fun 'n healthy in Moreland!. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2017 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 18(1). Disponible en: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85026747492&doi=10.1186%2Fs12889-017-4625-9&partnerID=40&md5=546ae0c9ca0aede962a8abbeea4698a9 [ Links ]

21. Wright K, Suro Z. Using community-academic partnerships and a comprehensive school-based program to decrease health disparities in activity in school-aged children. J Prev Interv Community [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 42(2): 125-39. DOI: 10.1080/10852352.2014.881185. [ Links ]

22. Xu F, Ware RS, Leslie E, Tse LA, Wang Z, Li J, et al. Effectiveness of a Randomized Controlled Lifestyle Intervention to Prevent Obesity among Chinese Primary School Students: CLICK-Obesity Study. PLoS One [Internet] 2015 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 10(10): e0141421. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26510135 [ Links ]

23. Quizán-Plata T, Villarreal Meneses L, Esparza Romero J, Bolaños Villar A V, Diaz Zavala RG. Programa educativo afecta positivamente el consumo de grasa, frutas, verduras y actividad física en escolares Mexicanos. Nutr Hosp [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 30(3): 552-61. Disponible en: http://www.aulamedica.es/nh/pdf/7438.pdf [ Links ]

24. Llargues E, Recasens MA, Manresa J-M, Bruun Jensen B, Franco R, Nadal A, et al. Four-year outcomes of an educational intervention in healthy habits in schoolchildren: the Avall 3 Trial. Eur J Public Health [Internet] 2017 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 27(1): 42-7. DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckw199 [ Links ]

25. Habib-Mourad C, Ghandour LA, Moore HJ, Nabhani-Zeidan M, Adetayo K, Hwalla N, et al. Promoting healthy eating and physical activity among school children: findings from Health-E-PALS, the first pilot intervention from Lebanon. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 14: 940. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25208853 [ Links ]

26. Bere E, Klepp K-I, Øverby NC. Free school fruit: can an extra piece of fruit every school day contribute to the prevention of future weight gain? A cluster randomized trial. Food Nutr Res [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 58: 23194. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4131001/pdf/FNR-58-23194.pdf [ Links ]

27. Meyer U, Schindler C, Zahner L, Ernst D, Hebestreit H, van Mechelen W, et al. Long-term effect of a school-based physical activity program (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in children: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS One [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 9(2): e87929. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24498404 [ Links ]

28. Wang J, Lau WP, Wang H, Ma J. Evaluation of a comprehensive intervention with a behavioural modification strategy for childhood obesity prevention: a nonrandomized cluster controlled trial. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2015 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 15: 1026. Disponible en: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12889-015-2535-2?site=bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com [ Links ]

29. Klakk H, Chinapaw M, Heidemann M, Andersen LB, Wedderkopp N. Effect of four additional physical education lessons on body composition in children aged 8-13 years - a prospective study during two school years. BMC Pediatr [Internet] 2013 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 13(1). Disponible en: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84885563805&doi=10.1186%2F1471-2431-13-170&partnerID=40&md5=209fbee5a10090eaca2459fec4e7d533 [ Links ]

30. Vanelli M, Monti G, Volta E, Finestrella V, Gkliati D, Cangelosi M, et al. "GIOCAMPUS" - An effective school-based intervention for breakfast promotion and overweight risk reduction. Acta Biomed [Internet] 2014 [citado 21 de octubre de 2017]; 84(3): 181-8. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24458162 [ Links ]

Received: May 23, 2019; Accepted: August 09, 2019

text in

text in